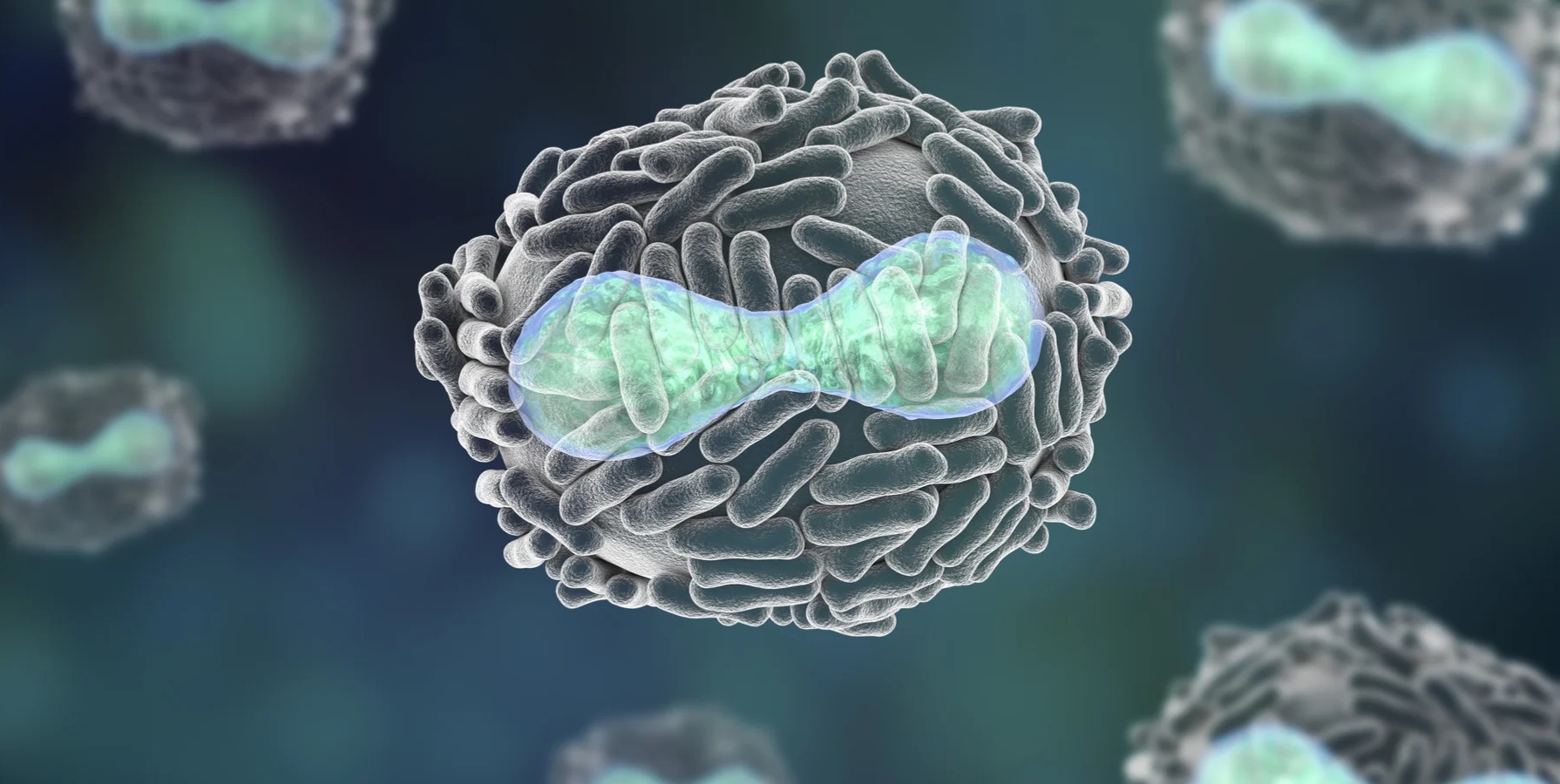

In 1545, a devastating epidemic swept through Mexico’s highlands, cutting down up to 80% of the native population in what was then the Aztec realm. Known as “cocoliztli” (Nahuatl) for “pestilence”, this outbreak, followed by another in 1576, claimed up to 17 million lives, devastating the Aztec people. For centuries, its cause remained a mystery, with guesses ranging from measles to typhus. But a 2017 study published January 2018 in “Nature”, shifts the spotlight: DNA from 500-year-old teeth points to Salmonella enterica as the culprit, offering the first genetic evidence of what felled millions after European contact.

Teeth the Nail in the Coffin

Researchers, led by Johannes Krause of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, analyzed skeletal remains from the Teposcolula-Yucundaa cemetery in Oaxaca, a site tied to the 1545–1550 “cocoliztli”. They extracted DNA from the teeth of 29 individuals, 24 linked to the epidemic. Using a metagenomic tool called MALT, they sifted bacterial DNA, finding matches to Salmonella enterica in ten samples. Further sequencing pinned it to the rare strain Paratyphi C, a pathogen causing enteric fever, marked by high fever, vomiting, and often death if untreated. This strain, is now scarce, but it was deadly then, and it ravaged the Aztec population.

A European Bioweapon?

The timing, 26 years after Cortés’s arrival, suggests a European source, but the study reveals no proof the Spanish brought Salmonella Paratyphi C. A separate 2017 paper identified the same strain in a Norwegian woman’s remains from around 1200 CE, showing it existed in Europe 300 years before Mexico’s outbreak. But this raises questions: if it was in Europe so early, why no major epidemics there? Did the Mexican strain come with conquistadors? We’ll address that later. Pre-Spanish contact graves at Teposcolula-Yucundaa do lack Salmonella however, hinting it was new in 1545, yet its path to Mexico remains a mystery.

Outbreak Beyond Conquest

Smallpox ravaged the Aztecs in 1520, upwards of 7 million estimated deaths, but cocoliztli dwarfed it, peaking decades later. The study suggests Paratyphi C exploited a population weakened by earlier diseases, poor nutrition, and displacement from Spanish campaigns, though it wasn’t necessarily their import. Its rarity in Europe, with only that single Norwegian case centuries prior, which contrasts sharply with Mexico’s mass die-off, making its sudden dominance an oddity unexplained by conquest alone.

Immunity Unlikely

The CDC and WHO note that 1–4% of people infected with Salmonella Typhi become chronic carriers, harboring it for months or years post-infection; think Typhoid Mary, who carried Typhi in her gallbladder and infected dozens in the early 1900s. While Salmonella Paratyphi C can linger in rare human carriers (persisting in the gut without symptoms after infection) such immunity requires prior exposure. For the Spanish or their slaves in 1545, this seems improbable. No evidence shows widespread outbreaks in Europe or West Africa before 1519; a single Norwegian case from circa 1200 marks its presence, not population resistance. Without repeated contact, neither group likely carried the protective edge to escape cocoliztli’s wake.

Chronicles of the Plague

Spanish chroniclers offer a glimpse into cocoliztli’s toll. Bernardino de Sahagún, a Franciscan friar documenting the 1576 outbreak in the “Florentine Codex“, wrote that “many died” with high fever, black tongue, & bleeding, fitting enteric fever, and he too fell ill himself, surviving to record it. Toribio de Benavente, known as Motolinía, estimated the 1545 epidemic killed 60–90% of “New Spain’s” populous, noting “Indians died in heaps”. Sahagún later observed Africans and Spanish sickened as well in 1576, suggesting the disease crossed lines, alluding to the aforementioned lack of immunity.

Limits of the Evidence

The Teposcolula-Yucundaa findings of Salmonella in ten of 24 epidemic victims, tie it to cocoliztli. No other pathogens like plague or measles appeared in these samples. The absence of Paratyphi C in pre-1519 graves supports its novelty in Mexico, but without tracing it to Spanish arrivals, its source remains a mystery. Today, this strain is rare, controlled by modern medicine, leaving its 16th-century surge puzzling.

Origins of earlier Smallpox Outbreak

Smallpox reached Mesoamerica in 1520 through Francisco de Eguía, an enslaved African who landed as part of a mission against Hernán Cortés, not with him. Diego Velázquez, Cuba’s Spanish governor, sent Pánfilo de Narváez with 900 men, including Eguía, to arrest Cortés in May 1520 for defying orders and seizing the conquest’s reins in 1519. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, in “The True History of the Conquest of New Spain“, writes Eguía arrived sick in Veracruz, infecting Cempoala, a coastal native town near Veracruz. The disease spread via Cortez’s native allies, chiefly Tlaxcalans, to Tenochtitlán, killing millions. Cortés had left Tenochtitlán to confront Narváez, before the outbreak, defeated him, and returned to find a plague killing the city’s people. In his 1520 letter to Charles V, he reported a pestilence had struck while he was away.

Carnage Amongst the Pestilence

Spanish chroniclers painted a vivid, grim picture of Aztec violence in Tenochtitlán. Bernal Díaz del Castillo recounted “cages of men fattened” for sacrifice and “skulls of the sacrificed” stacked in racks, their flesh later eaten with chili sauce, while Cortés noted “human flesh hung up in the marketplaces” and priests cutting open chests atop pyramids, appalled yet detailed in his observations. Francisco López de Gómara echoed this, writing of limbs severed post-sacrifice, consumed as casually as beef. These accounts gain weight from the Templo Mayor’s tzompantli, excavated since 1978, where tens of thousands of skulls, some with cut marks, confirm mass sacrifice over decades, aligning with Díaz’s racks. Knife-scarred bones and dismembered remains from the site, analyzed in studies like those by INAH (2015), further back the chroniclers’ claims of ritual carnage, grounding their words in physical evidence beyond Spanish pens.

A Plague Wrought by God?

With no clear-cut explanation for the millions ravaged by this outbreak which essentially wiped the Aztecs off the face of the earth. And science reconfirming the validity of the Spanish chronicler’s macabre historical accounts. Which in recent decades have been dismissed as colonizer fables, due to the takeover of academia, by ideologues hell bent on historical revisionism. Perhaps Gonzalo de Ortiz, (an encomendero), said it best, in the Relaciones geográficas “God sent such sickness upon the Indians, that three out of four perished.”

Come back to AncientHistoryX.com for more uncompromising articles.