The ancient Sumerian city of Ur, located in modern-day Iraq, stands as a testament to Mesopotamia’s urban achievements during the Early Dynastic period (c. 2900–2334 BCE). However, its archaeological record reveals a catastrophic flooding event around 3050 BCE (5000 years BP), which has long puzzled scholars. Initially interpreted as a local fluvial incident by Sir Leonard Woolley in the 1920s, recent interdisciplinary research integrating geological and climatological data suggests that this event was part of a broader environmental transformation driven by Holocene sea-level rise. This article re-examines the causes and implications of Ur’s flooding, emphasizing the interplay between climatic shifts and urban resilience.

Woolley’s Excavations and Initial Interpretations

Sir Leonard Woolley’s excavations at Ur uncovered a distinct layer of alluvial silt, approximately 3.7 meters thick, separating earlier occupational phases from later ones. He attributed this “flood stratum” to a sudden, localized change in the Euphrates-Tigris fluvial system, dismissing broader flood narratives as mythological. Woolley’s conclusion aligned with mid-20th-century archaeological paradigms, which prioritized site-specific explanations over regional climatic factors. However, his work established Ur’s flood as a pivotal event in Mesopotamian studies, sparking debates about its scale and causes.

New Evidence: Sea-Level Rise and Fluvial Reorganization

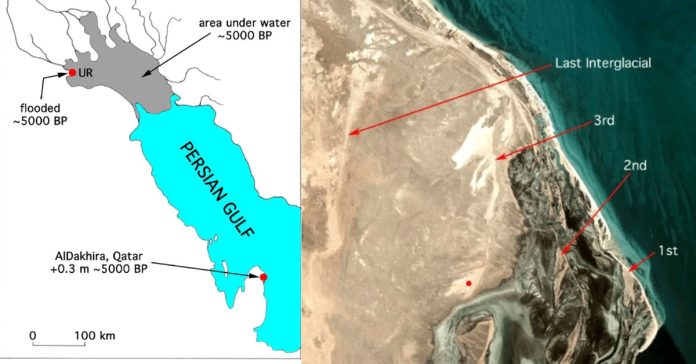

Recent palaeoclimatic studies in the Arabian Gulf region, particularly in Qatar, indicate that sea levels peaked at +0.3 meters above present levels around 5000 BP (3050 BCE). This rise likely triggered a cascade of environmental changes in Mesopotamia:

- Fluvial Reorganization : Elevated sea levels impeded the natural drainage of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, causing sedimentation, channel avulsions, and prolonged flooding in low-lying urban centers like Ur.

- Groundwater Inundation : Rising sea levels elevated regional groundwater tables, saturating soils and destabilizing foundations, which would have rendered large-scale agriculture and urban infrastructure untenable.

These processes align with geological evidence from Ur, where waterlogged sediments and disrupted architecture corroborate prolonged inundation.

Comparative Analysis: Lagash and Regional Flooding Patterns

Similar environmental crises are documented at Tell al-Hiba (ancient Lagash), where excavations revealed site-wide destruction layers dated to the late third millennium BCE. Though later than Ur’s flood, Lagash’s stratigraphy shows repeated flooding episodes linked to hydrological instability, suggesting that Mesopotamian cities faced recurrent threats from climatic and fluvial shifts. This pattern underscores the vulnerability of early urban centers to sea-level-driven disruptions, particularly in deltaic regions.

Implications for Mesopotamian Urban Decline

The flooding of Ur coincided with a period of political and economic decline in Sumer, traditionally attributed to conflicts or trade disruptions. However, environmental stressors likely exacerbated social instability:

- Agricultural Collapse : Saturated soils and salinization would have reduced crop yields, undermining Ur’s economic base.

- Urban Abandonment : Persistent flooding may have prompted migrations to higher elevations, as seen in shifts toward northern Mesopotamian cities like Mari and Assur.

This synthesis challenges earlier narratives of abrupt collapse, instead framing Ur’s decline as a gradual response to environmental pressures.

Conclusion

The flooding of Ur exemplifies the profound impact of Holocene sea-level rise on ancient civilizations. By integrating Woolley’s archaeological insights with modern geological data, we can reinterpret this event as a symptom of systemic climatic change rather than an isolated fluvial accident. Such interdisciplinary approaches not only refine our understanding of Mesopotamian history but also offer lessons for contemporary coastal cities facing rising seas and hydrological uncertainty.

References

1.”The Flood: Mesopotamian Archaeological Evidence.”

2. Sea-level data from Qatar and fluvial reorganization

3 “The Flooding of Lagash: Evidence for Urban Destruction” (2024).