Introduction: Unraveling the Tin Enigma

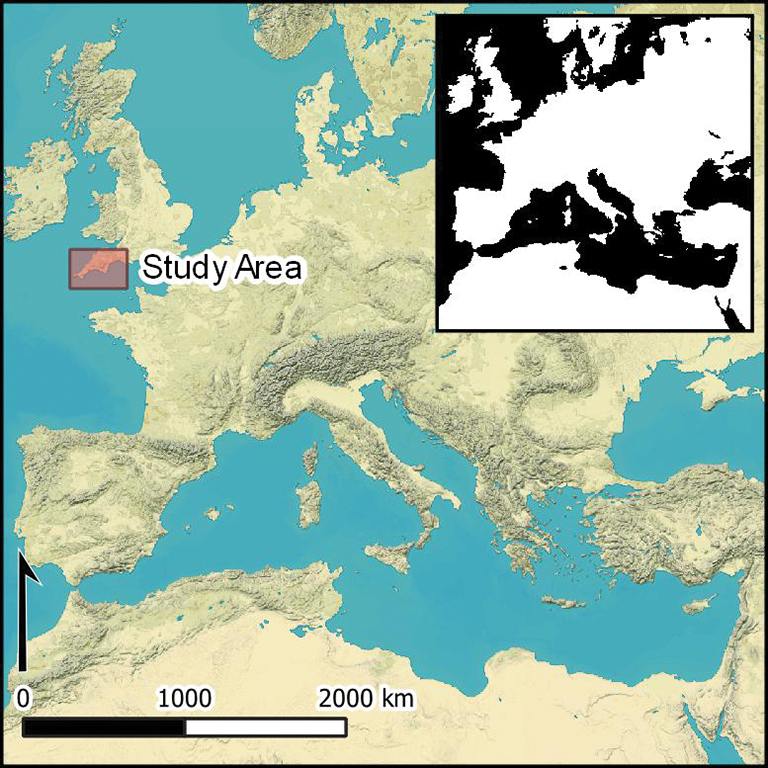

For over two centuries, the question of where Bronze Age societies sourced their tin, remained unanswered. the scarce yet indispensable metal for crafting bronze, has perplexed archaeologists. A ground breaking study, published in Antiquity in 2025, has finally illuminated this mystery, revealing that tin mined 3,300 years ago in Cornwall and Devon, Southwest Britain, was traded up to 4,000km to fuel the technological and cultural advancements of Eastern Mediterranean civilizations. Led by Dr. Alan Williams and Dr. Benjamin Roberts of Durham University, this research employs cutting-edge chemical and isotopic analyses to trace tin from British mines to shipwrecks off Israel, France, and Britain’s own coastlines.

This discovery not only confirms Britain’s pivotal role in the Bronze Age. It also redefines its prehistoric communities as integral players. These as a vast, interconnected trade network that shaped the ancient world. Far from peripheral, these small farming villages were defiant hubs of global commerce. Their tin enabling the bronze that defined an age. A clear doorway, a precursor to the acceptance on not only the Tin trade through the Atlantic coast and Mediterranean. But also across the Atlantic itself into the Americas for Copper. But more on that on another article.

The Geological Bounty of Cornwall and Devon

Cornwall and Devon boast Europe’s richest and most accessible tin deposits, primarily cassiterite, a tin oxide mineral eroded from granite veins into alluvial beds. Unlike the labour-intensive hard-rock mining required elsewhere, these alluvial deposits, often buried under layers of silt, sand, and gravel, were easily worked by Bronze Age communities using basic techniques. These include digging, washing, crushing, and smelting. The Antiquity study details how virtually every valley draining tin veins in these regions contained such deposits, with depths varying from a few meters upstream to tens of meters downstream. This geological abundance, estimated at 2.5 million tonnes of historical tin production, gave Cornwall and Devon a near-monopoly on European tin by the medieval period, a dominance that likely began in prehistory.

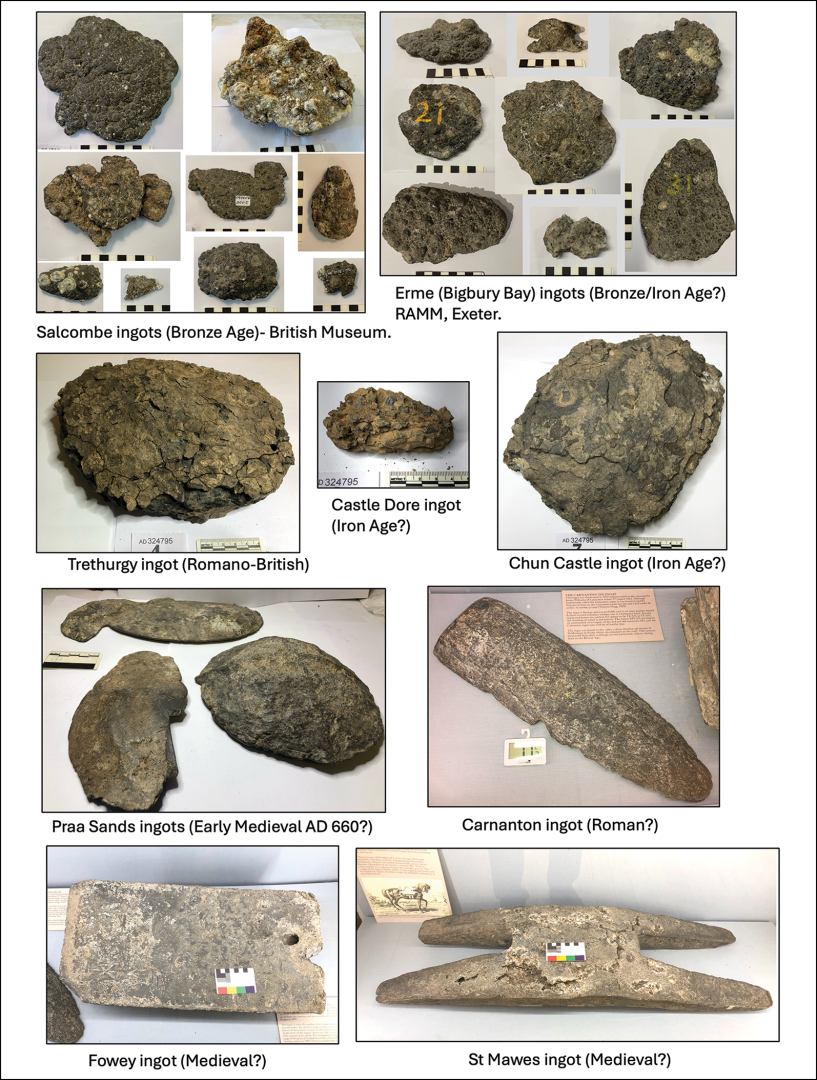

Archaeological evidence supports early tin extraction. Artefacts like flat axes, palstaves, and cauldrons, unearthed during 19th-century reworking of alluvial beds, indicate significant Bronze Age activity. A structure at Sennen, dated to 2400–2100 BC, contained Beaker pottery and stone tools with high tin concentrations, suggesting their use in ore crushing. These finds, coupled with the region’s coastal proximity, positioned Cornwall and Devon as ideal trade hubs, their tin ingots shipped across the Celtic Sea to continental Europe.

The Architects of the Tin Trade

The tin trade was a collaborative effort involving Cornish and Devonian communities, continental traders, and Mediterranean elites. Small farming villages, likely led by local chieftains, managed tin extraction and initial processing. The Antiquity study emphasizes their integration into a broader network, challenging notions of isolation. Classical texts by Pytheas, a Greek explorer who traveled Britain around 320 BC, describe tin trading from Ictis, a tidal island. Some believe it to be St Michael’s Mount, now under excavation by the Durham team. Pytheas’ account, preserved in later works, details a 30-day route from Ictis to the Rhone’s mouth, highlighting the efficiency of this trade.

The research team, including Dr. Alan Williams, Dr. Benjamin Roberts, and Dr. Kamal Badreshany from Durham University, collaborated with institutions like the Curt-Engelhorn-Zentrum Archäometrie (CEZA) in Mannheim, Germany. Their interdisciplinary approach combined archaeology, geology, and chemistry, building on prior studies by scholars like Ernst Pernicka and Daniel Berger, who in 2019 suggested British tin in Mediterranean contexts. Traders from France, Sardinia, and Cyprus acted as intermediaries, ferrying tin to Mycenaean Greece, Hittite Anatolia, and other advanced societies, whose demand for bronze drove this complex network.

A Timeline of Tin’s Ascendancy

The Bronze Age, spanning roughly 2500–800 BC in Britain, marked a shift from copper to tin-bronze around 2100 BC, earlier than most of Europe. This “bronzization,” as termed by scholars, began in Northwest Europe, with Britain and Ireland leading the transition to full tin-bronze (8–15% tin) for tools, weapons, and ornaments. By 1900 BC, tin-bronze dominated British metallurgy, spreading to Scandinavia and Central Europe by 1700 BC and reaching the Aegean and Egypt by 1500–1400 BC. The Antiquity study pinpoints 1300 BC as a peak for British tin in Mediterranean shipwrecks, with the Rochelongue wreck (c. 600 BC) showing continued trade into the Iron Age.

Tin extraction in Cornwall likely began around 2100 BC, coinciding with the arrival of Beaker populations from continental Europe, who introduced metallurgy. Radiocarbon-dated finds, such as a tin-studded hairband from Whitehorse Hill (c. 1750–1600 BC), confirm early tin working. Pytheas’ 320 BC account provides a literary anchor, describing an established trade. The trade’s scale, estimated at tens of tons annually, matched the hundreds of tons of copper circulating, underscoring tin’s critical role.

Mapping the 4,000km Trade Route

The tin trade route, as reconstructed by the Antiquity study, spanned 4,000km from Cornwall to the Levant. Tin ingots, smelted into crude or “H”-shaped forms, left coastal sites like St Michael’s Mount or Salcombe, crossing the Celtic Sea to France. From there, traders transported them down rivers like the Rhone, reaching Mediterranean ports. Shipwrecks at Salcombe and Erme (Britain), Rochelongue (France), and off Israel’s coast (Uluburun, Hishuley Carmel, Kfar Samir) mark this path. The Israeli wrecks, dated to 1300 BC, contain tin isotopically matched to Cornwall, while Rochelongue’s 600 BC ingots extend the timeline.

The route likely involved staging posts in Sardinia and Cyprus, flourishing trade hubs that connected Britain to Mycenaean and Hittite markets. Sea currents and winds, as noted by Roberts, favoured Southeastern Mediterranean routes, though Late Bronze Age conflicts (e.g., Egyptian-Hittite wars) occasionally disrupted trade. This network, described as a form of pre-modern globalization, linked disparate cultures, with tin’s value rising exponentially along the journey.

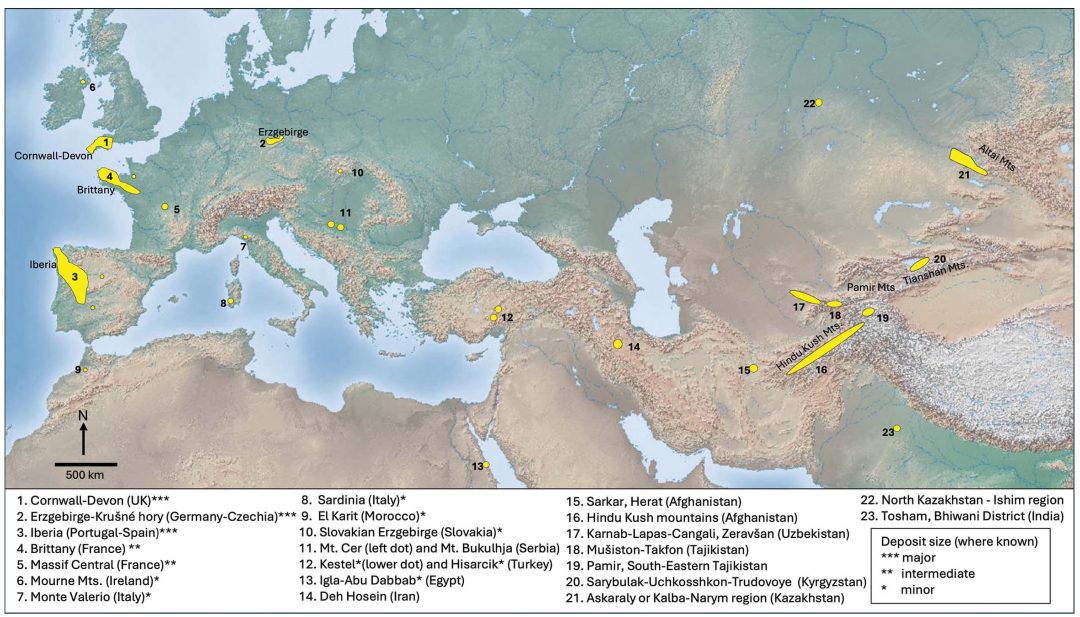

Tin as the Lifeblood of Bronze

Tin’s scarcity, found in few major deposits like Cornwall, the Erzgebirge, Iberia, and Central Asia, made it a prized commodity. Bronze, typically 90% copper and 10% tin, offered superior hardness, castability, and aesthetics compared to copper or arsenical copper. The Antiquity study estimates that tens of tons of tin were traded yearly to meet Mediterranean demand, enabling the production of weapons, tools, and jewellery that defined advanced civilizations. Without tin, the Bronze Age’s technological leap would have faltered, as copper alone lacked the necessary properties.

Britain’s tin integrated small communities into a pan-continental economy, supporting palaces and cities like Mycenae and Hattusa. The trade’s cultural impact was profound, fostering exchanges of ideas and technologies. For Cornwall and Devon, tin was their first major export, elevating their economic and social significance. The study challenges narratives of British peripherality, presenting these communities as defiant architects of a globalized Bronze Age.

Scientific Breakthrough: Fingerprinting Ancient Tin

The Antiquity study’s innovation lies in its three-pronged analytical approach: trace element, lead isotope, and tin isotope analyses. The team sampled 142 tin ores from Cornwall, Devon, and other European deposits (e.g., Erzgebirge, Brittany, Iberia). They analyzed 98 samples for lead isotopes and 23 for tin isotopes, supplemented by CEZA’s dataset. These methods “fingerprinted” Cornish tin, distinguishing it from other sources via unique indium, antimony, and lead signatures. Ingot analyses from Mediterranean shipwrecks, processed using IsoplotR software, confirmed Cornwall’s dominance, refuting earlier theories favouring Central Asian sources.

A 2019 study by Berger et al. had suggested British tin in Israeli wrecks based on indium levels. Nevertheless, it lacked comprehensive ore data. The Antiquity team’s extensive sampling, including Tregurra and Tolgarrick ores and smelting experiments, provided conclusive evidence. While geoarchaeologist Wayne Powell argues for Central Asian contributions, the study’s data suggests these were minor by 1500 BC. Therefore it was Cornwall supplying the bulk of Mediterranean tin. This methodological rigour sets a new standard for provenancing studies.

Cultural and Historical Implications

The tin trade positions Bronze Age Britain as a cornerstone of ancient innovation. Cornish tin enabled the bronze artefacts that defined Mycenaean and Hittite cultures, from intricate jewellery to formidable weapons. Pytheas’ account, now scientifically validated, underscores Britain’s long-standing trade prominence, a legacy that persisted into the medieval period’s tin monopoly. Excavations at St Michael’s Mount, ongoing in 2025, aim to uncover Ictis’ infrastructure, potentially revealing smelting sites or trade depots.

This discovery challenges Eurocentric biases that marginalized Britain’s prehistoric communities. Far from rustic backwaters, Cornish villages were sophisticated nodes in a global network, their tin a catalyst for cultural exchange. The trade’s scale, reaching tens of tons annually, reflects organizational complexity. Most likely involving Beaker elites or maritime traders like the Veneti of Brittany. This narrative of connectivity and agency invites us to rethink Britain’s role in shaping the ancient world.

Counterarguments and Ongoing Debates

Some scholars, like Wayne Powell, argue that Central Asian tin, from sites in Kazakhstan, remained significant. For this, he cites isotopic matches in early Mediterranean bronzes (2000–1600 BC). However, The Antiquity study counters that by 1500 BC, Cornish tin dominated due to its accessibility and volume. Minor European deposits Minor deposits (e.g., Brittany, Iberia) likely served local needs, unable to match Cornwall’s output. The debate persists, with future analyses of Central Asian ores needed to clarify their role. The study’s focus on shipwreck ingots, rather than finished bronzes. Therefore strengthening its case, as ingots reflect raw material origins more directly.

Future Directions: Excavating Ictis and Beyond

The Durham team’s excavations at St Michael’s Mount, suspected as Pytheas’ Ictis, aim to uncover physical evidence of tin trade infrastructure. For this they seek docks, smelters, or storage sites. Further isotopic studies, building on the Antiquity dataset, could refine trade route reconstructions. Exploring whether land-based routes through Central Europe supplemented maritime paths. Integrating ancient DNA and artefact analyses may reveal the social structures behind this trade. Therefore illuminating the lives of Cornish tin workers. These efforts promise to deepen our understanding of Britain’s Bronze Age legacy.

Conclusion: Britain’s Defiant Legacy

The Antiquity study by Williams, Roberts, and colleagues proves that Cornwall and Devon’s tin, mined by small farming communities. In brief, it shows what they believe to be, Britain’s first continental export. Travelling no less than 4,000km to power Mediterranean civilizations. This trade, is now validated by Pytheas’ ancient texts and modern science. In sum, it redefines Bronze Age Britain as a dynamic hub of global commerce. As excavations at St Michael’s Mount unfold, the story of these defiant tin traders continues to challenge our perceptions, affirming their role in forging an era. Britain’s tin was not just a commodity. It was a catalyst for a golden age, its legacy etched in the bronze that shaped history.