New 3D imaging and morphometric data challenge the straightforward classification of Skhul I as Homo sapiens, suggesting a complex hominin ancestry.

Revisiting a Pioneering Discovery

First excavated in 1931 at Mugharet es-Skhul (the “Cave of the Children”) on Mount Carmel, Israel, the fossil designated as Skhul I remains central to the study of early human burials and the evolution of Homo sapiens.Researchers initially considered the remains, dating to approximately 140,000 years ago, as a transitional form between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans.

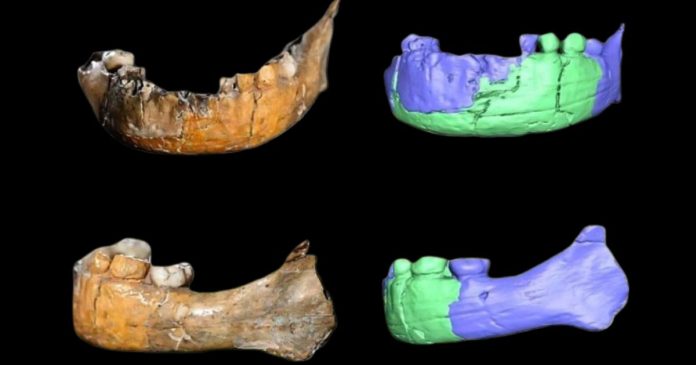

Recent advances in paleogenetics and craniofacial morphology led Dr. Bastien Bouvier and his colleagues to re-examine this specimen and publish their findings in the journal L’Anthropologie (2025).Through CT scanning and 3D modeling, the team has produced a refined analysis of the neurocranium and mandible, offering new perspectives on the taxonomic status of Skhul I.

Historical Context and Early Excavations

British archaeologists Dorothy Garrod and Theodore McCown discovered the cave site in 1928 and conducted the excavation.They uncovered remains from at least 26 individuals—ten relatively complete skeletons and sixteen fragmentary specimens. Skhul I, the first individual found, belonged to a child aged approximately 3 to 5 years, with a cranial capacity of around 1100 ml.

At the time, McCown classified the remains as Paleoanthropus palestinensis, a proposed transitional form between Neanderthals and modern humans. Over time, this label shifted toward proto-Cro-Magnon and eventually early Homo sapiens, though not without significant debate regarding possible hybrid ancestry.

New Morphological Analysis: A Composite Identity

Using high-resolution CT scans, Bouvier’s team analyzed the preserved portions of the neurocranium and mandible, comparing them with those of Homo sapiens, Homo neanderthalensis, and other Late Pleistocene hominins.

Key Findings Include:

- Neurocranial Profile: The cranial shape and vascular patterning resemble Neanderthals, yet the structure of the bony labyrinth within the inner ear aligns more closely with Homo sapiens.

- Basicranial Features: The tilt of the foramen magnum—where the spine connects to the skull—is notably oblique, paralleling the morphology observed in Homo rhodesiensis (e.g., Kabwe I).

- Mandibular Structure: The inner (lingual) surface of the jaw exhibits a pronounced posterior tilt of the planum alveolare (alveolar plane), an archaic trait also found in Skhul X, another juvenile from the same site.

- Dental Morphology: The teeth are arranged in a rounded arc similar to both eastern and western Neanderthal juveniles. While the enamel surface differs from Neanderthal patterns, Skhul I shows a mid-trigon crest split—an enamel-dentine junction trait shared with Neanderthals.

These complex and sometimes conflicting traits underscore the limitations of rigid taxonomic categorization and suggest the individual may have emerged from a population with mixed ancestry.

Taxonomic Ambiguity and the “Skhul Paleodeme”

The study’s authors argue that morphological evidence alone does not allow a definitive assignment of Skhul I to Homo sapiens.Instead, they advocate for classifying the individual within a broader “Skhul paleodeme”—a term acknowledging a unique local population with both archaic and modern features.

The potential for genetic analysis remains tantalizing but controversial. Dr. Anne Malassé, a co-author of the study, notes that while DNA extraction from the well-preserved neurocranial bones is theoretically possible, it would be invasive and potentially damaging to this unique specimen. No such attempt has yet been made.

Burial Context and Cultural Significance

Despite the child’s unusual cranial morphology, the archaeological context suggests that the group buried Skhul I with the same care as they did other members. There is no evidence of special treatment or ritual differentiation in the burial process.

“The body was secondarily compressed, but archaeologists observed no deviation in funerary practice,” explains Dr. Malassé. “This suggests the child was a fully accepted member of the community.”

This burial, among the oldest intentional human interments known, raises broader questions about the emergence of symbolic behavior and its association with Homo sapiens. The case of Skhul I blurs the line between cultural and biological identity, further complicating the narrative of early modern human evolution in the Levant.

Conclusion: Ancestry Beyond Labels

The reanalysis of Skhul I contributes to ongoing debates regarding the complex web of interactions among Pleistocene hominins. It challenges simplistic dichotomies between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, underscoring the Levant’s role as a crossroads of human evolution.

While definitive classification may remain elusive without DNA data, the new study affirms the importance of advanced imaging in reconstructing ancient morphology and revisiting long-standing assumptions about human ancestry.

Reference

Bouvier, B. et al. (2025). New Analysis of the Neurocranium and Mandible of the Skhul I Child: Taxonomic Implications and Cultural Considerations. L’Anthropologie. Link to publication