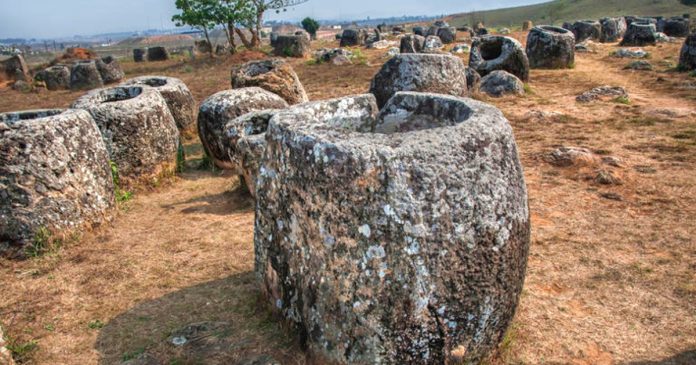

The Laos Plain of Jars captivates explorers with its enigmatic megaliths, scattered across landscapes that evoke tales of ancient rituals. Imagine wandering through misty hills in northern Laos, where giant stone jars rise from the earth like silent guardians of forgotten secrets. These massive vessels, some towering three meters high, cluster in groups or stand solitary, inviting endless questions about their creators and purpose.

Unearthing the Past: Early Explorations

The story of the Laos Plain of Jars began unfolding in the late 1800s, when Western scholars first noted the peculiar formations. French archaeologist Madeleine Colani dove deeper in the 1930s, excavating around the jars and unearthing fragmented skeletal remains alongside artifacts such as glass and carnelian beads, ceramic vessels, ear discs, spindle whorls, iron and bronze tools, jewelry, and ground stone items. Based on this material culture, she connected the sites to Southeast Asia’s Iron Age, spanning roughly 500 BC to 500 AD, and proposed they played a role in burial customs.

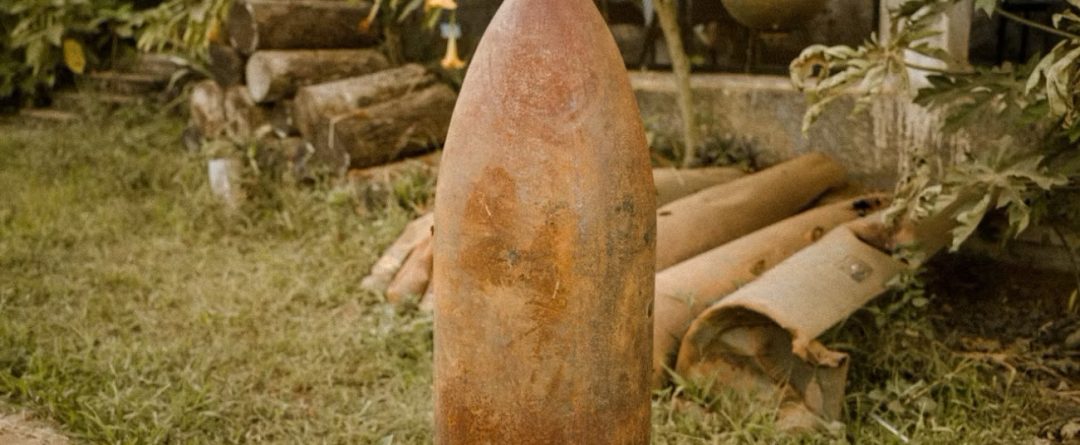

The Vietnam War from 1964 to 1973, often called the Secret War in Laos, scattered the landscape with unexploded ordnance as the United States dropped over 2 million tons of bombs, leaving an estimated 80 million undetonated and stalling archaeological progress for decades. In the 1990s, Japanese and Lao researchers picked up the thread, digging test pits and finding similar items. Their dates ranged wildly, from prehistoric eras to more recent times. Unexploded ordnance restricted access, leaving over 90 percent of the more than 100 known sites untouched by traditional archaeology.

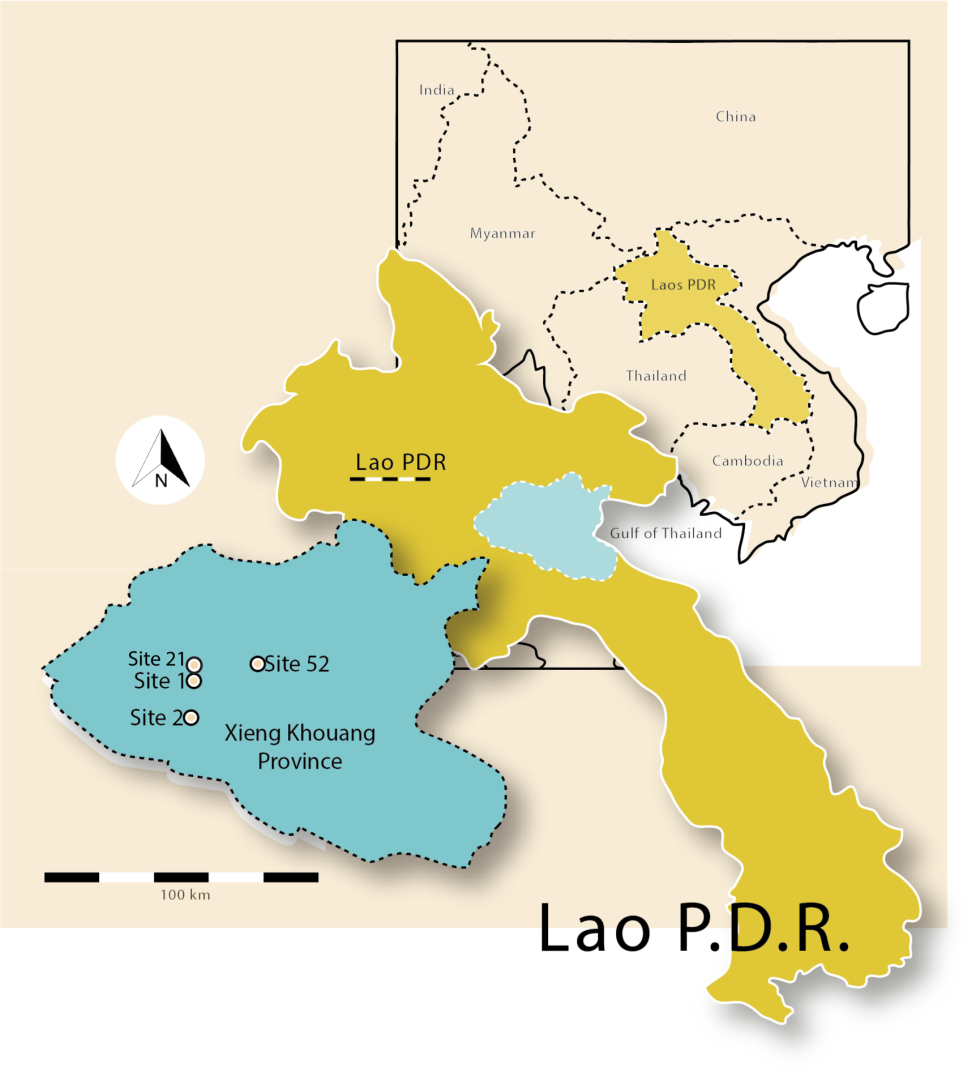

Fast forward to recent years, and international teams have ramped up efforts. Excavations at prominent locations like Site 1, Site 2, and Site 52 revealed diverse burial methods. At Site 1, archaeologists discovered primary interments alongside secondary burials, where bones bundled together or rested in ceramic vessels.

Limestone slabs and sandstone pavements marked these spots, accompanied by siliceous quartz breccia boulders tied to mortuary rituals, such as placements over ceramic jars containing human remains. Artifacts, including glass beads, iron tools, and ceramic shards, painted a picture of a society deeply invested in honoring the dead.

Decoding the Jars’ Timeline

What truly sets the Laos Plain of Jars apart is the challenge of pinpointing when these megaliths first appeared. Carved from sandstone or conglomerate, the jars can weigh up to 30 tons, raising puzzles about how ancient people transported them over rugged terrain from distant quarries.

A 2021 study employed cutting-edge techniques to tackle these mysteries. Using optically stimulated luminescence on sediments beneath the jars at Site 2, researchers dated their placement to between 1240 BC and 660 BC. This finding shifts the timeline back to the late second millennium BC, earlier than many expected. At Site 52, sediment ages reached around 43,000 years, but these likely represent natural soil layers predating human activity.

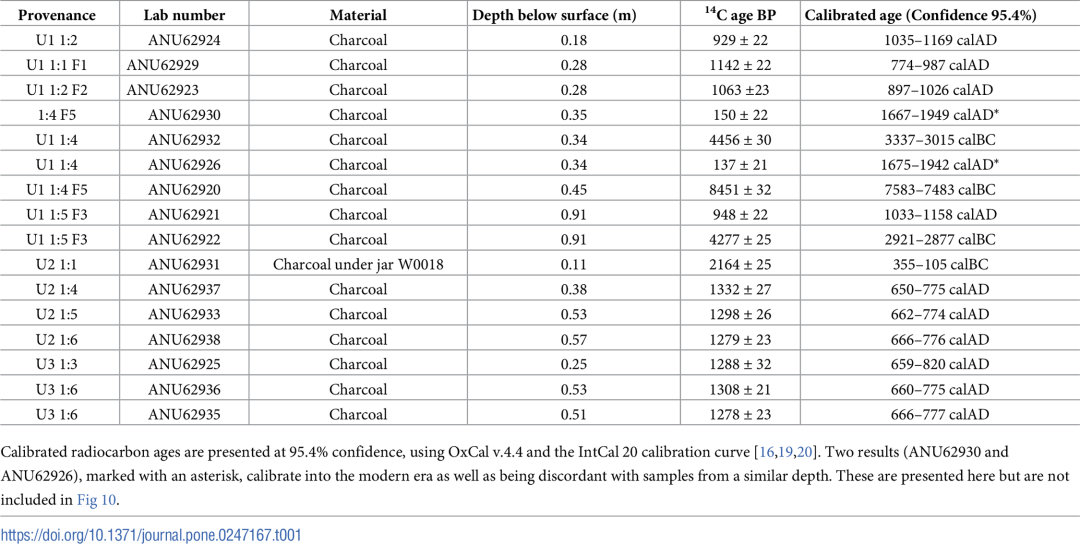

Radiocarbon dating added layers to the story. Charcoal and bone from burial contexts at Sites 1 and 2 pointed to mortuary practices from the 9th to 13th centuries AD. A significant gap emerges: people positioned the jars millennia ago, yet later communities continued rituals around them. This enduring use underscores the sites’ lasting spiritual importance, bridging ancient origins with medieval traditions.

Tracing the Stone: Origins and Craft

Sourcing the raw material for the jars unlocks another piece of the puzzle. At Site 1, the 316 megaliths mostly consist of sandstone, with the nearest potential quarry at Phoukeng, about 8 kilometers away. Incomplete jars and similar rock types there hinted at a connection.

U-Pb dating of zircons within the stone confirmed this link. These tiny minerals serve as geological timestamps, revealing formation ages. Samples from a broken jar at Site 1 matched those from Phoukeng, with dominant zircon clusters dating from 260 to 500 million years old. Crafting such behemoths demanded expertise; workers hollowed them using iron tools, aligning with Iron Age technology, though the early dates suggest possible reevaluation.

The landscape itself tells a tale. The plain sits at 1,100 meters above sea level, surrounded by Paleozoic mountains. Soils vary from reddish-brown clays to pale alluvial deposits, influencing preservation and excavation challenges.

Legends and Alternative Theories

Beyond scientific inquiry, the Laos Plain of Jars sparks a wealth of folklore and speculation. Local legends speak of giants who once roamed the land. In one popular tale, King Khun Cheung commanded a giant army to victory, then celebrated by brewing rice wine in enormous vessels. These jars, the story goes, stored the brew for their feasts, explaining their hollow forms and scattered placement.

Practical theories have also emerged over time. Some suggest the jars collected rainwater in a region prone to dry spells, providing vital storage for communities. Others propose they held grains or food supplies, protected from pests and weather in the upland environment.

Mortuary ideas dominate many discussions. Colani herself leaned toward burial functions, where bodies decomposed inside before bones transferred elsewhere—a practice seen in other Southeast Asian cultures. Yet, intact jars rarely contain remains, fueling debates. Perhaps they served as markers for underground graves or symbolic containers for spirits.

More exotic notions include astronomical alignments, with jars positioned to track celestial events. Or they might represent territorial boundaries in ancient trade routes. No single theory satisfies all evidence, and the absence of written records leaves room for imagination. These ideas reflect humanity’s drive to explain the inexplicable, blending myth with emerging facts.

Lingering Enigmas and Future Horizons

The Laos Plain of Jars continues to baffle. Why construct over 2,000 jars across so many sites? Their purpose (ritual, practical, or both) remains elusive. Burials cluster around them, but the connection feels layered, like echoes across time.

Unexploded ordnance slows discovery, with clearance efforts inching forward. New sites surface annually through surveys, expanding the map of this megalithic culture.

Looking ahead, more dating and analysis promise clarity. Teams plan to sample additional sediments and artifacts, piecing together social structures and trade networks. Tourism surges, but visitors must tread carefully, guided by locals who navigate the dangers.

In the end, the Laos Plain of Jars embodies ancient ingenuity and mystery. Builders long gone left monuments that endure, challenging us to uncover their world. Each excavation peels back layers, revealing a civilization that revered death, stone, and the landscape in ways we still strive to understand. As research evolves, this Southeast Asian wonder keeps its secrets close, inviting the curious to explore further.

Source Legend

- Shewan, L., O’Reilly, D., Armstrong, R., Toms, P., Webb, J., Beavan, N., Luangkhoth, T., Wood, J., Halcrow, S., Domett, K., Van Den Bergh, J., & Chang, N. (2021). Dating the megalithic culture of Laos: Radiocarbon, optically stimulated luminescence and U/Pb zircon results. PLoS ONE

- Legacies of War. (n.d.)

- Colani, M. (1935). Mégalithes du Haut-Laos (Hua-Pan). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.