Megalithic dolmens appear across continents, yet their purpose and origin remain contested. In central Jordan, the Murayghat site offers a rare opportunity to examine these structures in detail. Located southwest of Madaba, Murayghat features over ninety-five dolmens and standing stones arranged across a limestone ridge. This article examines Murayghat’s architectural features, burial landscape, and broader implications for understanding global megalithic traditions.

Murayghat Dolmens

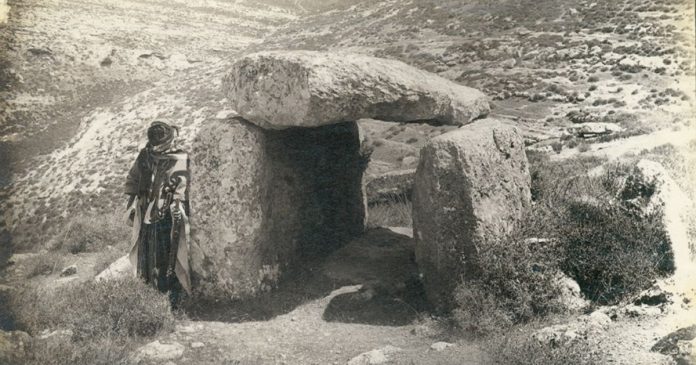

Megalithic dolmens dominate the limestone ridge of Murayghat, southwest of Madaba, where ritual architecture replaced domestic settlement during Early Bronze Age I. The site includes over ninety-five dolmens, many collapsed, yet still arranged with deliberate orientation across natural terraces and elevated knolls. These megalithic dolmens vary in size, elevation, and construction method, but most use fractured limestone slabs placed with intentional alignment. Some dolmens rest on platforms, others integrate bedrock directly, and a few show signs of circular enclosures or tumuli. The largest concentration appears in Area 4, where dolmens align with the central knoll and overlook surrounding valleys and wadis.

Standing stones appear in rows, isolated placements, and architectural walls, often facing dolmen clusters or natural features. Hadjar al-Mansub, a 2.4-meter monolith, (right) stands apart from the site, facing northeast with a carved groove and smoothed surfaces. Its orientation and isolation suggest symbolic placement, possibly marking a route, boundary, or ceremonial threshold. Megalithic dolmens at Murayghat do not resemble domestic architecture; no hearths, roofs, or permanent floors were found in excavated areas. Instead, structures consist of upright slabs, curved walls, and shallow depressions carved into exposed bedrock with no evidence of roofing.

Architectural Complexity and Ritual Function

Trench 9 revealed a rectangular enclosure built around a raised bedrock platform with cup-marks and shallow rectangular carvings. Walls consist of orthostats placed without bonding, often supported by packing stones or abutting natural crevices in the limestone.

Room 5 in Trench 8 contains a central standing stone, a bench-like bedrock shelf, and a large limestone mortar nearby. Other trenches show curved walls, double-faced constructions, and additive architecture suggesting episodic use and evolving spatial needs. Pottery includes large V-shaped bowls with alternating ledge handles, possibly used for communal feasting or ritual consumption.

Basalt grinders, flint tools, copper needles, and horncores suggest mixed symbolic and practical activity across the site. Residue analysis on one grinder revealed ochre, a pigment often associated with marking, preparation, or ceremonial use. Megalithic dolmens and associated features appear designed for visibility, interaction, and symbolic engagement rather than shelter or storage. Researchers found no domestic debris, reinforcing the interpretation of Murayghat as a ritual landscape rather than a residential settlement.

Burial Landscapes and Societal Transition

Megalithic dolmens are hypothesized as burial monuments, paralleling Early Bronze Age sites like Mount Nebo and Jebel Mutawwaq. Some dolmens were built on platforms or had associated stone circles, indicating formalized mortuary practices and spatial planning.

The visibility of these structures suggests territorial marking, ancestral presence, and transformation of natural terrain into cultural landscape. Murayghat’s megalithic dolmens emerged during a period of societal disruption following the decline of Chalcolithic prestige systems.

Climate shifts, reduced trade, and loss of symbolic artifacts marked the end of established socio-political frameworks in the southern Levant. Communities responded by creating new ritual landscapes, emphasizing burial, visibility, and collective identity through monumental architecture. Megalithic dolmens reflect this transition, offering a spatial solution to ideological and organizational uncertainty. The site likely served as a regional meeting place, facilitating negotiation, ritual, and social cohesion without centralized authority. Architecture at Murayghat lacks uniformity, suggesting contributions from multiple groups or evolving ceremonial needs over time. This additive construction style contrasts with the planned symmetry of domestic settlements or fortified enclosures from later periods.

A Global Question

Megalithic dolmens of Jordan are not isolated phenomena; similar traditions appear across continents, cultures, and time periods. From Carnac in France to Nabta Playa in Egypt, from Göbekli Tepe to the Korean dolmens, the pattern repeats with striking consistency. How is it that all around the globe we see this standing stone architecture, often without direct cultural contact or diffusion? Were humans all on the same thought arc independently, responding to landscape, mortality, and memory with similar monumental forms?

What does that say about us, our cognitive architecture, and our shared need to mark, gather, and remember visibly? Megalithic dolmens may be one node in a global pattern of ritual geometry, shaped by necessity, symbolism, and stone. This convergence invites forensic comparison, not romantic speculation, and demands clarity in documenting what is truly shared. Rather than viewing these structures as anomalies, we might consider them as expressions of a shared human response, but to what?

For more megaliths check out Dolmen of Menga: Engineering Megalithic Structure