Known as Monte Sierpe, (“Serpent Mountain”) 35 km from the Pacific coast is a band of more than 5,200 precisely aligned holes. They march in neat rows up a barren Andean ridge. In 1931, National Geographic pilot Robert Shippee flew over Peru’s Pisco Valley and captured their first image. The photgraph documented the 1.5-kilometer pattern stretching like a punch card etched into the earth. Published in 1933, they would puzzle the world for nearly a century. Their placement sat curiously at the intersection of ancient roads between the Chincha Kingdom’s heartland and Inca administrative centers.

For decades, theories ranged from defensive trenches to water cisterns, geoglyphs, or even extraterrestrial landing strips. But a recently published has decoded its true purpose. Monte Sierpe they’ve determined was “A big smart abacus built into the ground”. But it’s this authors more apt comparison that it was the world’s first physical blockchain. A decentralized, immutable, transparent ledger. One used to record trade and tribute that lasted centuries.

Numerical Grid in the Earth

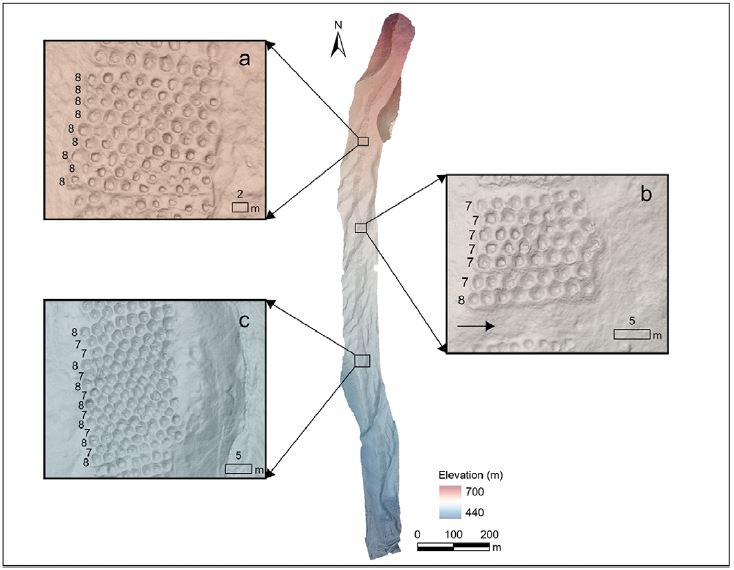

Using high-resolution drone photogrammetry and GNSS mapping, researchers documented the site with unprecedented precision. The holes are each one to two meters wide and one meter deep. They are organized into at least 60 distinct sections, separated by deliberate gaps. Each section representing repeating numerical patterns. Patterns that reveal intentional design. Here are three examples of the 60 sections.

| Section | Pattern | Total Holes |

|---|---|---|

| One | 9 rows × 8 holes | 72 |

| Two | 6 rows × 7 + 1 row × 8 | 50 |

| Three | 12 rows alternating 7 and 8 (7-8-7-8…) | 90 (6×7 + 6×8) |

This pattern rules out natural formations. It reflects structured data, a physical database where each hole represents one unit of goods, labor, or obligation. As such each section functions as a block in a chain. The entire 1.5 km band, stretching from valley floor to hillside, forms a visible ledger readable by anyone who could count.

This organization mirrors modern blockchain architecture. Bitcoin uses blocks to group transactions into a tamper-resistant chain. Similarly Monte Sierpe used earthen sections to aggregate hole-based entries. Once dug, the holes could not be easily altered (refilling 5,200 pits would require massive labor) making the system practically immutable. Like the blockchain, each transaction was public and verifiable. Where as, farmers, merchants, herders, and officials could walk the ridge and audit the counts in real time.

Phases of Usage

Phase 1: The Chincha Permissionless Barter Network (AD 1000–1400)

Monte Sierpe emerged during the Late Intermediate Period under the Chincha Kingdom, one of the most powerful coastal polities in pre-Hispanic Peru. Colonial records describe a population of over 100,000, supported by 30,000 male tribute payers. They had an economy driven by specialized producers: 10,000 farmers, 10,000 fishers, and 6,000 merchants who operated vast trade networks using llama caravans inland and balsa rafts along the coast.

The kingdom’s wealth flowed from coastal agriculture (maize, cotton, squash, chili), marine resources (dried fish, guano fertilizer), and highland imports (wool, charqui, copper, silver, emeralds). Merchants exchanged coastal cotton for Ica Valley prestige goods and carried Andean metals to Pacific ports. Monte Sierpe sat at the nexus of these routes, positioned above extensive irrigation canals and linked to pre-Hispanic roads.

In this context, the Band of Holes functioned as a permissionless barter marketplace. Highland caravans arrived seasonally, after harvest or herding cycles, and traders used the holes to stage, display, and tally goods. A farmer might deposit 80 maize cobs into 80 holes in Section (a). A herder owing 20 wool bundles from a prior exchange would leave 20 holes empty as a public IOU. The running tally preserved memory across seasons, preventing fraud and enabling reciprocity; the cornerstone of Andean exchange.

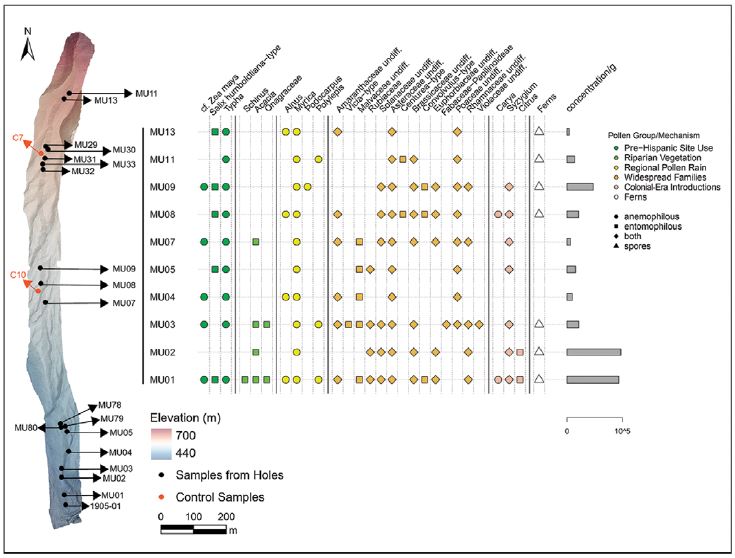

Microbotanical evidence supports this. Sediment from 19 holes contained maize, squash, amaranth, cotton, and chili pollen, along with marine diatoms and highland plant traces (Podocarpus, Polylepis). Control samples outside the band lacked these, proving the holes held several commodities, not just one crop.

Phase 2: The Inca Permissioned Tribute Chain (AD 1400–1532)

When the Inca conquered the Chincha in the 15th century, they did not destroy the system; they upgraded it. The empire imposed a decimal administrative structure. They organized populations into hierarchical units. Within this structure they conducted periodic censuses to levy tribute in goods (e.g., textiles, grain, metals) and labor (via the mit’a corvée system). This was not arbitrary; it was a scalable governance framework for an empire spanning 2,500 miles and 10–12 million people. This ensured efficient resource extraction and control over different groups.

Monte Sierpe was repurposed as a tribute verification station. Each section now likely represented an ayllu (kin-based taxpayer group) or commodity quota. The repeating numerical patterns, 7s, 8s, and implied 10s, aligned with Inca accounting logic. This parallelled the knotted-string Quipus used by state administrators. A local khipu recovered nearby (Barraza et al., 2022) shows similar additive and hierarchical grouping, reinforcing the connection.

Under Inca rule, a section would represent a community’s commodity obligation. If 42 units were delivered to section (b), 42 holes were filled; the 8 empty holes visually signaled a shortfall. Officials could audit compliance at a glance. The monumental, fixed nature of the site made accounting public and communal, unlike portable Quipus controlled by elites. It was a landscape-scale smart contract, self-executing, self-enforcing, and resistant to tampering.

Beyond Quipus

Quipus were portable, elite-controlled. Monte Sierpe was monumental, communal, and tactile. It served where public accountability mattered most; at the intersection of local autonomy and imperial control. It allowed farmers to verify their contributions, merchants to settle disputes, and Inca officials to enforce quotas. All using the same transparent system.

Radiocarbon dating from charcoal to pottery at the nearby defensive settlement proved continued use for 200 to 400 years. For centuries this earthen blockchain operated without failure.

Conclusion: The Original Decentralized Blockchain

Monte Sierpe is no longer a mystery. it’s societal mastery a physical blockchain that turned the landscape into a durable, distributed database. It recorded thousands of transactions across generations, using earth as memory, holes as entries, and sections as blocks.

It proves that decentralized trust is not a modern invention. Five hundred years before Satoshi Nakamoto, the Chincha and Inca already understood the power of an immutable, transparent, peer-verified ledger.

They didn’t need a computer to code. They had counting, consensus, and the mountain itself. Next time someone says blockchain is revolutionary, tell them about Monte Sierpe The original chain, carved in stone, running on human trust, and still readable today.