Tributsch Inca masonry techniques a tebuttal. In an “Earth as we know it” article on Inca stone masonry Tony Trupp presents one of the most thorough and evidence‑based treatments of the subject available online. His emphasis on hammerstones, wedges, ramps, and collective labor as the primary techniques is accurate and well supported by both Spanish chroniclers and modern experimental archaeology. On this point, I am in full agreement. The Inca did not need lost technologies or mystical plants to achieve their remarkable stonework. They relied on ingenuity, patience, and skill.

Where I take issue is with Tony’s treatment of Helmut Tributsch’s 2017 paper, On the reddish, glittery mud the Inca used for perfecting their stone masonry. In his article, Tony cites Tributsch only to dismiss him, reducing the paper to a misinterpretation. This is a myopic characterization. While I do not endorse Tributsch wholesale, I believe his work deserves to be represented accurately, not cherry‑picked into a straw man.

The Quote in Question

“A 2017 paper by Tributsch explored this topic further. In it, he quotes Cieza de León mentioning ‘melted gold’ being used in place of mortar, suggesting that excerpt is evidence for his proposed acidic stone softening liquid. But rather than this being evidence for stone softening, it might be better understood as referring to the T and O shaped clamps that they used to join their stones together at a few of these sites, including Ollantaytambo and Qoricancha. Molten metal was poured directly into these carved recesses to help lock them in place. The melted gold here may have simply been bronze, which is known to have been used on these clamps.”

This passage is the crux of my objection. Tony collapses Tributsch’s entire paper into this single interpretation, presenting it as if the author’s only contribution was to misread Cieza de León. In reality, Tributsch’s paper is far broader, exploring pyrite mud, bacterial oxidation, silica gel formation, and the possibility of plant sap enhancement. To reduce it to ‘melted gold’ is disingenuous.

What Tributsch Actually Argued

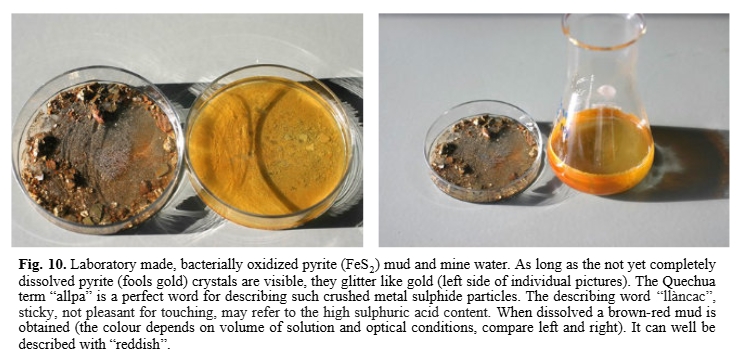

Tributsch’s paper is speculative, but it is grounded in chemistry, geology, and ethnographic context. He examined the reddish, glittery mud known as llancac allpa, mentioned by chroniclers, and proposed that it may have played a role in finishing Inca stone joints. His hypothesis was that acid mud derived from pyrite oxidation could superficially soften silica‑rich stone surfaces, creating a viscoelastic silica gel that allowed for polishing and tight fitting.

He further suggested that plant saps containing oxalic acid, referenced in Andean folklore, could have enhanced this process. Tributsch tied these ideas to observed vitrified joints at sites like Ollantaytambo and Sacsayhuaman, arguing that the shiny, glassy interfaces could be explained by silica gel solidification. This was not a claim of magical stone‑melting plants, but a proposal rooted in mineralogical plausibility and cultural context. One that’s echoed in Mayan plasters.

The Clamp Hypothesis vs. Tributsch’s Hypothesis

Tony’s clamp explanation is valid. Bronze clamps were indeed used at sites like Qoricancha and Ollantaytambo. Molten metal poured into carved recesses is a well‑documented technique. But presenting this as the definitive correction to Tributsch is misleading. Clamps explain mechanical joining, while Tributsch was exploring surface finishing and vitrification. These are not mutually exclusive.

It is entirely possible that chroniclers conflated different practices, or that their descriptions were imprecise. The “melted gold” anecdote may refer to clamps in some cases, but Tributsch’s broader hypothesis about silica gel treatment addresses a different phenomenon: the shiny, vitrified joints that clamps alone cannot explain. By collapsing the two into one, Tony oversimplifies the debate.

Why Misrepresentation Matters

Accurate representation of sources is the bedrock of credible scholarship. When debunkers mischaracterize legitimate research, they erode trust in their own work. Readers who later discover the fuller scope of Tributsch’s paper may rightly question whether other sources have been similarly distorted. This damages the integrity of the debunking enterprise as a whole.

Moreover, dismissing speculative but plausible hypotheses without fair engagement stifles intellectual curiosity. Tributsch’s paper may not provide definitive proof, but it raises questions worth exploring. To caricature it into folklore is to shut down inquiry rather than encourage it. That is the opposite of what serious debunking should achieve.

The Evidence of Vitrified Joints

One of Tributsch’s key observations was the presence of shiny, glassy joints in Inca masonry. These vitrified surfaces are not easily explained by hammerstone work alone. Tributsch proposed that silica gel, formed through acid mud treatment, could account for these features. He even noted parallels with modern conservation techniques that use silica gels to preserve stone monuments.

Tony’s article sidesteps this evidence entirely. By reducing Tributsch’s work to metallurgical clamps this avoids addressing the actual phenomenon of vitrified joints. This is a critical omission, because it is precisely these surfaces that demand explanation beyond conventional stone‑hammering techniques.

Intellectual Rigor vs. Narrative Control

Debunking should be about intellectual rigor, not narrative control. When an article misrepresents a source to fit its preferred storyline, it ceases to be scholarship and becomes propaganda. The treatment of Tributsch’s paper is a case study in this failure. Instead of engaging with the hypothesis, the author cherry‑picks the most dismissible angle and presents it as the whole.

This approach may satisfy readers looking for simple answers, but it does nothing to advance understanding. It reduces complex debates to soundbites and undermines the credibility of the debunking community. If debunkers want to be taken seriously, they must hold themselves to the same forensic standards they demand of others.

My Position on Tributsch’s Hypothesis

I do not endorse Tributsch’s paper wholesale. There are legitimate questions about logistics, experimental verification, and the extent to which acid mud could have been applied in practice. But rejecting the paper outright without fair engagement is irresponsible.

By defending accurate representation, I am not defending pseudoscience. I am defending intellectual honesty. If debunking is going to raise the bar, it must do so consistently. That means engaging with speculative work fairly, even when the conclusion is ultimately rejection.

Conclusion: Deal With the Mud, Not the Spin

Tony’s article is strong, and his emphasis on hammerstones and patience is accurate. But his treatment of Tributsch (2017) is a misfire. By reducing the paper to clamps as the definitive explanation, he misrepresents the scope of the hypothesis. This is narrative cherry‑picking, not forensic debunking.

Debunking without honesty is just another narrative. If you’re going to cite Tributsch, deal with his acid mine runoff; not your own spin. That is the standard of forensic clarity we should demand, and it is the only way to raise the bar in public discourse.