For decades, archaeologists suspected that the coastlines of western Europe hid traces of early human engineering now lost beneath the sea. But few expected anything like what divers and researchers have now documented off the coast of Sein Island in Brittany. Beneath seven to nine meters of water lies a sprawling complex of stone walls—some massive, some delicate, all unmistakably human built; dating back nearly 7,000 years. These structures, revealed through high resolution seafloor mapping and confirmed by dozens of dives, represent one of the most ambitious coastal engineering projects ever identified from the Mesolithic period.

The findings challenge long held assumptions about the technological abilities of hunter gatherer societies living before the rise of farming in Brittany. These communities were not small or mobile groups. They mobilized collective labor and quarried large amounts of stone. They shaped monoliths and modified their coastline on a scale once linked only to later Neolithic builders. The structures near Sein Island are not simple fish traps or isolated walls. They form a coordinated system of constructions that reshaped an entire shoreline.

A Submerged Landscape Rediscovered

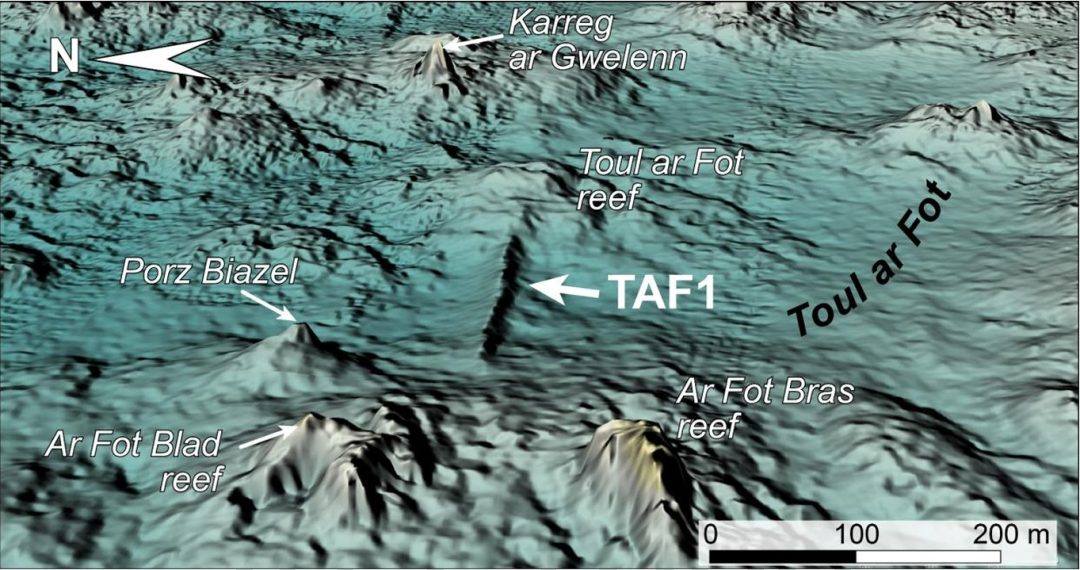

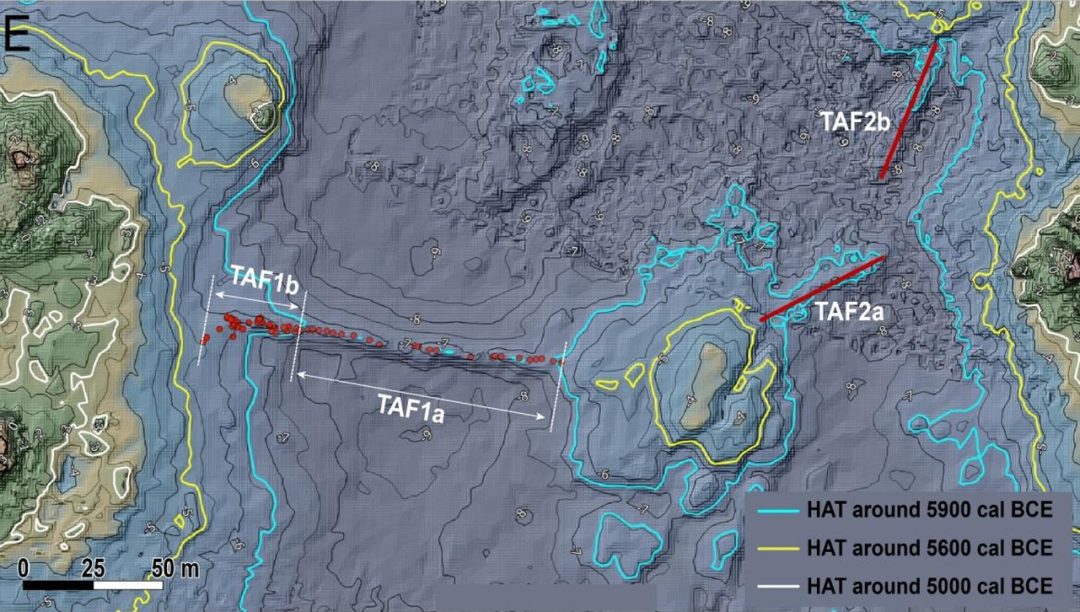

The stone structures were first detected not by divers but by technology. As part of France’s Litto3D program, airborne LIDAR and bathymetric mapping produced detailed digital elevation models of the seafloor. Researchers studying the maps saw long, straight ridges crossing natural valleys. These shapes did not match the region’s fractured granite geology. The anomalies led to several dive campaigns between 2022 and 2024. Divers confirmed the ridges were walls built from stacked blocks, upright slabs, and vertical monoliths.

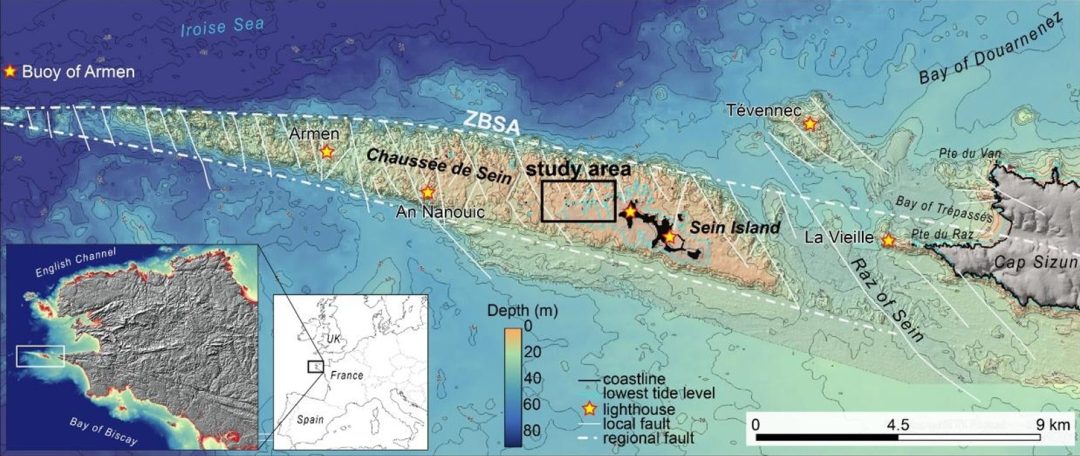

The underwater landscape around Sein Island is shaped by a granite plateau known as the Chaussée de Sein. The plateau is carved by intersecting faults that create long, narrow valleys. These valleys once formed natural channels above sea level. In the Mesolithic period, they were dry or intertidal zones ideal for building structures. These structures interacted with tides, currents, and marine life. Rising seas over 8,000 years submerged the constructions by more than 20 meters. This gradual flooding preserved the stone features in remarkable condition.

The Largest Wall: A Monument of Stone and Skill

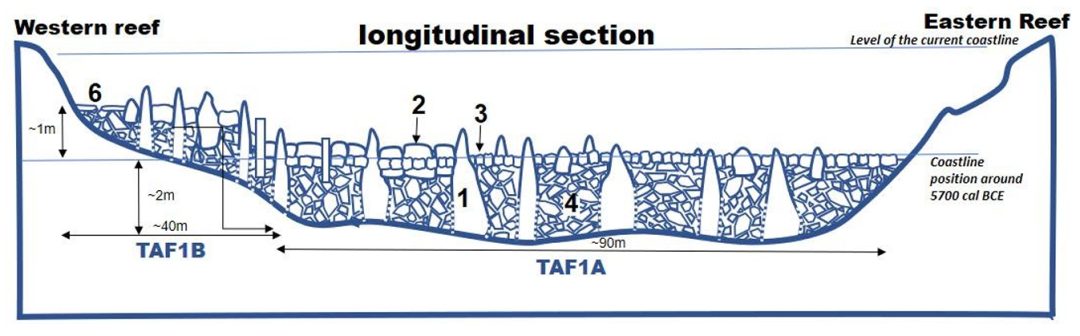

The most impressive structure is the largest wall, a stone construction stretching roughly 120 meters across one of the granite valleys. Even underwater, its scale is striking. The wall stands up to two meters high in places and spans more than twenty meters across from base to base. Its top is lined with dozens of upright monoliths, some nearly two meters tall, arranged in parallel rows. Between these monoliths, builders placed large vertical slabs, and behind them they packed hundreds of angular granite blocks to form a stable, sloping mass.

This is not a simple pile of stones. The wall’s cross section reveals a deliberate asymmetry: the northern side is wider and more heavily reinforced, clearly designed to resist the powerful swell that strikes the area from the north. The southern side slopes more gently toward what would have been a sheltered basin. This architectural choice suggests that the builders understood local hydrodynamics and engineered the wall to withstand centuries of wave action.

The largest wall is so well preserved that divers could map the positions of more than sixty monoliths still standing upright on its summit. Some lean slightly, others have fallen, but many remain anchored deeply within the structure, evidence of careful placement and long-term stability.

Other Walls Form a Network of Coastal Constructions

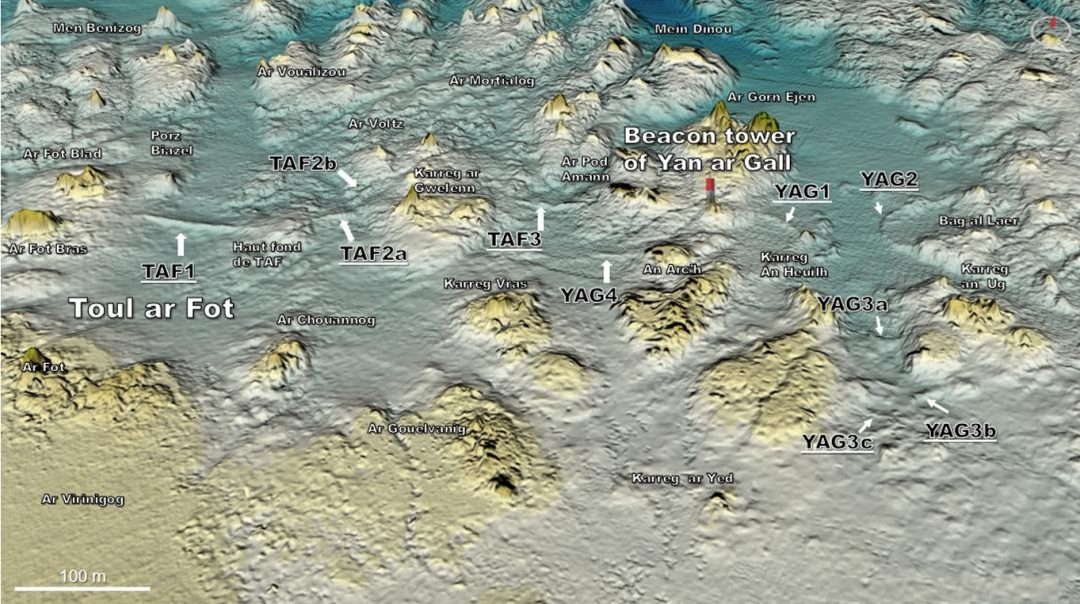

Beyond the main wall, researchers identified ten additional stone structures within a few hundred meters. These include:

Two medium sized walls built across neighboring valleys

Several smaller walls near a navigation tower east of the main site

Curved and angled walls that appear to adapt to natural rock formations

Low, narrow walls resembling classic fish weirs found elsewhere in Brittany

Some of these smaller walls are only half a meter high today, but their shapes and positions match known prehistoric fishing structures. Others are more substantial and share architectural features with the largest wall, including upright stones and carefully packed block fills.

Together, these constructions form a coherent system, not isolated efforts. They appear to have been built in phases over several centuries, adapting to rising sea levels and changing shoreline conditions. Some walls were placed at higher elevations than others, suggesting that as older structures became less effective due to submergence, new ones were built farther inland.

A Possible Quarry Hidden in Plain Sight

monoliths, Image Source: https://hal.science/hal-05406477v1, CC BY 4.0

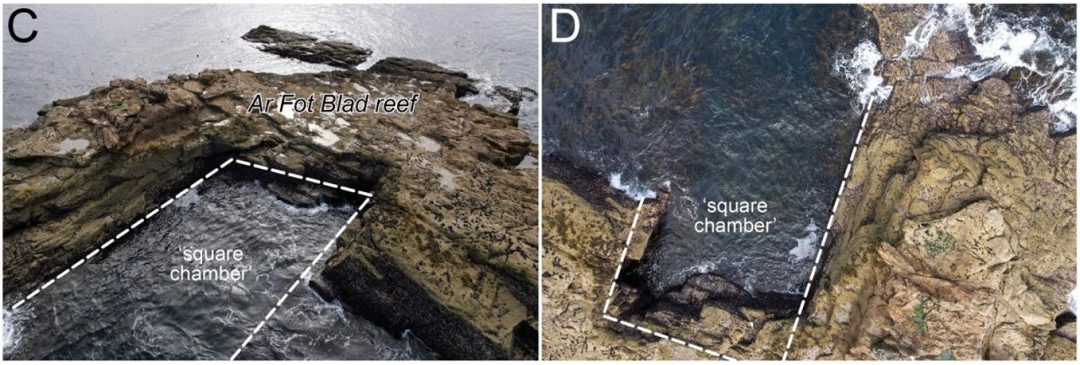

One of the most intriguing discoveries lies just west of the largest wall: a granite reef with a rectangular pit carved into its surface. This pit, nicknamed the “square chamber” by divers, is roughly 25 meters long, 10 meters wide, and 7 meters deep. Its edges are sharp and angular, lacking the rounded contours typical of natural erosion. The chamber is also unusually clean, with no accumulation of fallen blocks inside it.

The geology of the reef matches the stone used in the walls. The reef contains both coarse porphyritic granite and finer, biotite rich granite; exactly the two types found in the wall’s construction. The natural jointing of the rock would have allowed prehistoric builders to split off slabs and monoliths with relative ease.

Researchers avoid making a definitive claim, but the evidence strongly suggests the “square chamber” functioned as a quarry. It likely supplied the monoliths and slabs used in the walls. If correct, this would mark one of Brittany’s earliest stone‑quarrying operations. It would also predate the region’s famous Neolithic megaliths by centuries.

Engineering a Protected Lagoon

Why build such massive structures? The researchers propose two main interpretations.

The first is that some of the walls functioned as fish traps, similar to stone weirs found throughout Brittany. These traps rely on tidal cycles: fish enter the enclosure at high tide and become stranded as the water recedes. Several of the smaller walls match this pattern.

But the largest wall—and a few of the medium sized ones; are far too large and too heavily reinforced to be simple fish traps. Their asymmetrical design, strategic placement across valley mouths, and connection to natural reefs suggest a different purpose: protecting a shallow lagoon.

During the period of construction, the area south of the largest wall would have been a sheltered basin bordered by reefs. By closing the valley with a massive stone barrier, the builders could reduce wave energy entering the basin, creating a calm zone ideal for fishing, shellfish gathering, boat use, and other daily activities. This would have been especially valuable in a region known for violent swell and strong tidal currents.

In effect, the builders engineered their coastline, modifying the environment to create a stable, productive, and predictable marine habitat.

A Window Into Mesolithic Society

The scale and sophistication of these constructions reveal a society far more organized than previously assumed for the Mesolithic period. Building a 120meter stone wall with upright monoliths requires planning, cooperation, and repeated maintenance. The presence of multiple walls built at different elevations suggests long term occupation and adaptation to rising sea levels.

These communities were not simply wandering foragers. They were maritime specialists, deeply familiar with tides, currents, and stone working. Their engineering achievements foreshadow the monumental stone traditions that would emerge in Brittany a few centuries later.

The submerged walls off Sein Island offer a rare glimpse into a vanished world—a world where hunter gatherers reshaped their coastline with ingenuity and collective effort. As sea levels continue to rise today, these ancient constructions remind us that humans have long adapted to changing shores, leaving behind traces of resilience and creativity now hidden beneath the waves.

For More Ancient Megalithic engineering read, Dolmen of Menga: Engineering Megalithic Structure