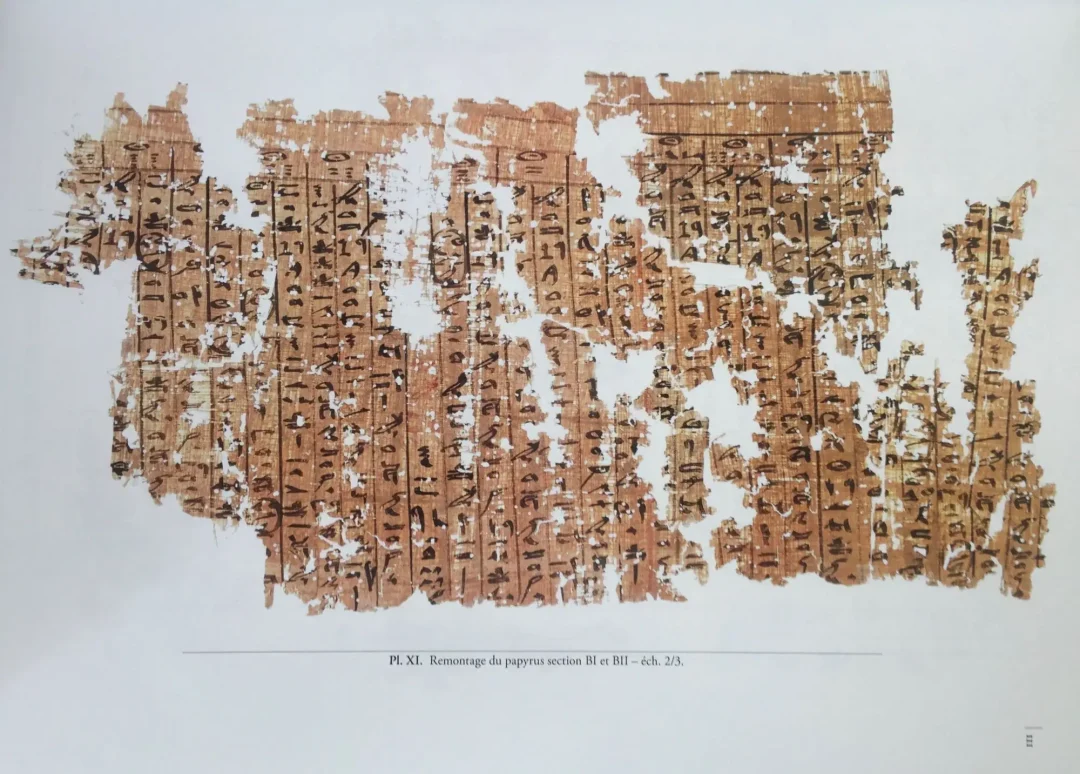

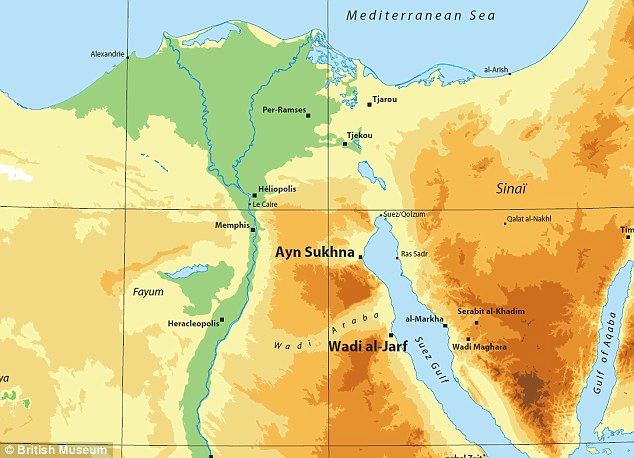

The Papyrus of Merer was unearthed in 2013 at Wadi el‑Jarf, a Red Sea port roughly 200 kilometers southeast of Cairo. This discovery offers a rare glimpse into the logistical operations behind limestone transport during the reign of Khufu. The believed builder of the Great Pyramid around 2580–2560 BCE. Excavated by a team led by Pierre Tallet, the documents—now recognized as the oldest papyri ever found in Egypt—record the daily activities of Inspector Merer and his crew as they ferried limestone from the Tura quarries toward Akhet‑Khufu.

As an alternative researcher, I approach these texts with a commitment to evidence and a critical eye toward mainstream interpretations. Especially when those interpretations rest on assumptions that extend beyond what the papyri actually state. This article reviews the historical context of the documents. Along with the role of Wadi el‑Jarf, and a full translation of Merer’s logbook. This article also examines how modern estimates (such as the idea of thirty 2–3‑ton blocks per trip) were developed. It evaluates alternative hypotheses about what the papyri truly represent. Finally, it introduces a counterargument grounded in environmental data from ancient Nile routes. Thus, offering a perspective that differs from traditional archaeological narratives.

Wadi el-Jarf: A Key to Authenticity and Context

The discovery of the Papyrus of Merer at Wadi el‑Jarf ties the documents firmly to Khufu’s reign. They also include limestone transport operations directed toward Akhet‑Khufu. This Red Sea port, established under Sneferu (circa 2675–2633 BCE), includes thirty‑one rock‑cut galleries for storing boats and a two‑hundred‑meter jetty, making it the oldest known artificial open‑sea harbor. The papyri were found in a pit between limestone blocks that sealed gallery G1. They survived because of the desert’s aridity and because a later disturbance preserved fragments above the water‑damaged layers.

In addition, the port supported expeditions to Sinai for copper and turquoise, but this activity never placed it within the Nile‑based logistics of Giza. What truly anchors the papyri to the Fourth Dynasty are the references to Akhet‑Khufu and to the high official Ankh‑haf. Pottery bearing the name of Merer’s team, “The Escort Team of ‘The Uraeus of Khufu is its Prow,’” also reinforces this connection by invoking the royal emblem of authority.

Perspective on the Location

While the discovery at Wadi el‑Jarf confirms the papyri’s authenticity and their connection to crews active under Khufu, the location itself raises important questions. The site is a remote Red Sea port. It’s far from the Nile corridor that linked the Tura quarries to the Giza plateau. If these documents served as central records for the Great Pyramid’s construction, their presence in a coastal storage gallery makes little sense, especially when officials in Memphis or Giza should have kept them.Memphis or Giza.

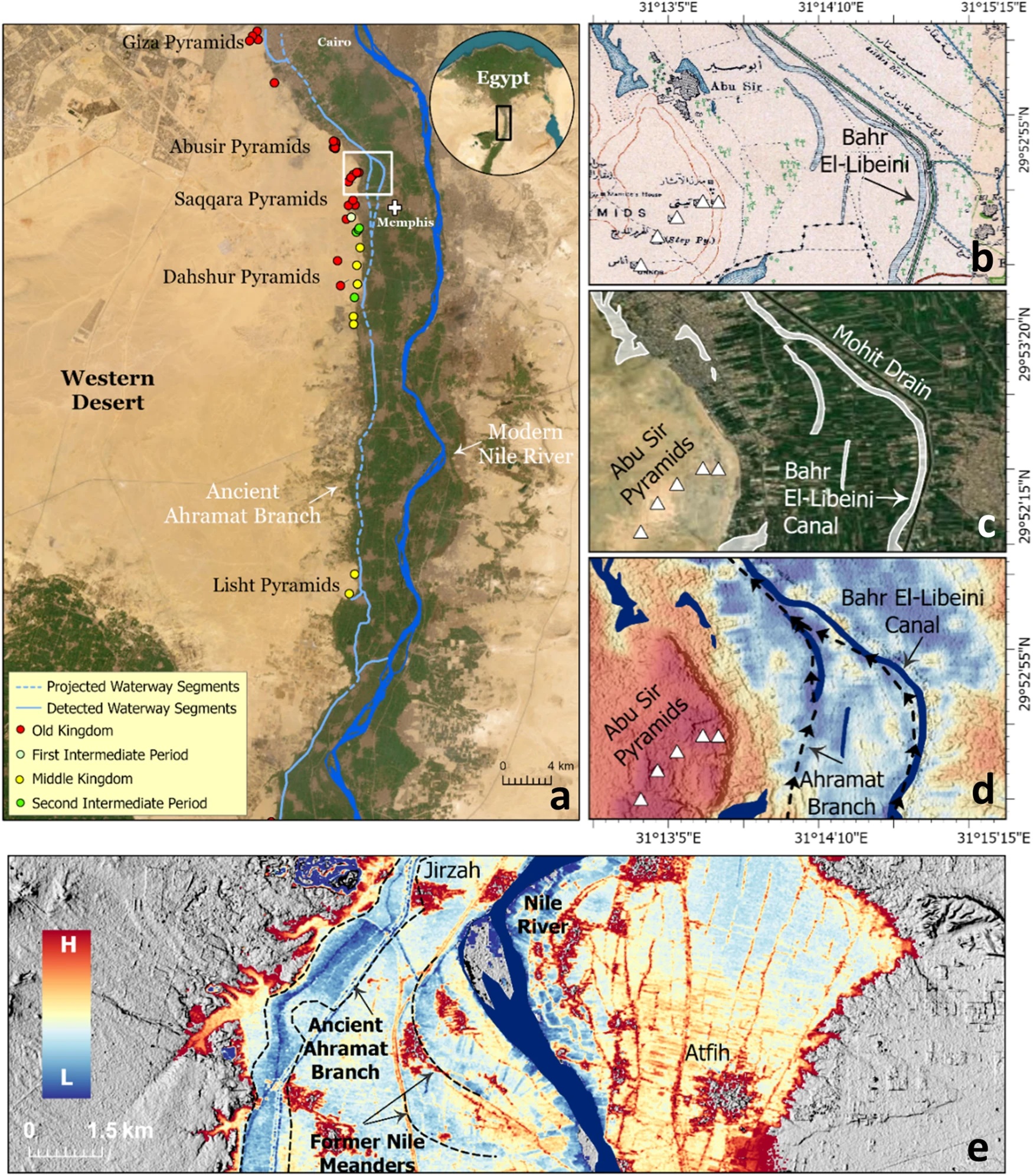

Their presence at Wadi el Jarf suggests they belonged to a mobile transport team whose duties extended beyond the Nile system. One which weakens the idea that the logbook represents the core administrative archive of the pyramid project. The PNAS study published in 2022, which reconstructs a now vanished Nile branch near Giza. The study reinforces this distinction by showing that the stone transport network operated inside the Nile Valley and never linked to the Red Sea port where the papyri surfaced.

Papyrus of Merer: The Details

The Papyrus of Merer consists primarily of two major documents. Papyrus Jarf A and Papyrus Jarf B. Along with several smaller associated fragments, all written in hieratic and cursive hieroglyphs. Merer, an inspector commanding the “Great” phyle, recorded the daily movements of his transport crew as they hauled limestone from Tura and worked on the dyke of Ro‑She Khufu. The surviving papyri date to the twenty‑sixth or twenty‑seventh year of Khufu’s reign and mention the high official Ankh‑haf. In addition, the documents offer insight into how a Fourth Dynasty transport team operated. However, they do not describe construction methods, workforce size, or the broader logistics of the Great Pyramid project. The late date in Khufu’s reign prompts scrutiny: were these tasks for the pyramid’s final stages or other projects?

Complete Translation of Merer’s Logbook

Below is the full translation of Papyrus Jarf A and B, Merer’s logbook, based on Tallet’s 2017 publication. Gaps reflect the papyri’s fragmented state, with “Day x+” indicating sequences where exact day numbers are missing.

Days 1-10

- First Day: [Fragmentary] Spend the day […] in […]

Day 2: [Fragmentary] Spend the day […] in? […]. - Day 3: [Cast off from?] the royal palace? […] sail[ing] [upriver] towards Tura, spend the night there.

- Day 4: Cast off from Tura, morning sail downriver towards Akhet Khufu, spend the night.

Day 5: Cast off from Tura in the afternoon, sail towards Akhet Khufu. - Day 6: Cast off from Akhet Khufu and sail upriver towards Tura […].

Day 7: Cast off in the morning from […]. - Day 8: Cast off in the morning from Tura, sail downriver towards Akhet Khufu, spend the night there.

- Day 9: Cast off in the morning from Akhet Khufu, sail upriver; spend the night.

- Day 10: Cast off from Tura, moor in Akhet Khufu. Come from […]? the aper-teams? […].

Merer Translation: Days 11-20

- Day 11: Inspector Merer spends the day with [his phyle in] carrying out works related to the dyke of [Ro-She] Khufu […].

- Day 12: Inspector Merer spends the day with [his phyle carrying out] works related to the dyke of Ro-She Khufu […].

- Day 13: Inspector Merer spends the day with [his phyle? …] the dyke which is in Ro-She Khufu by means of 15? phyles of aper-teams.

- Day 14: [Inspector] Merer spends the day [with his phyle] on the dyke [in/of Ro-She] Khufu […].

- Day 15: […] in Ro-She Khufu […].

- Day 16: Inspector Merer spends the day […] in Ro-She Khufu with the noble? […].

Day 17: Inspector Merer spends the day […] lifting the piles of the dy[ke …]. - Day 18: Inspector Merer spends the day […].

- Day 19: […].

- Day 20: […] for the rudder? […] the aper-teams.

Days 25-30

- Day 25: [Inspector Merer spends the day with his phyle [h]au[ling]? st[ones in Tura South]; spends the night at Tura South.

- Day 26: Inspector Merer casts off with his phyle from Tura [South], loaded with stone, for Akhet Khufu; spends the night at She Khufu.

- Day 27: Sets sail from She Khufu, sails towards Akhet Khufu, loaded with stone, spends the night at Akhet Khufu.

- Day 28: Casts off from Akhet Khufu in the morning; sails upriver Tura South.

- Day 29: Inspector Merer spends the day with his phyle hauling stones in Tura South; spends the night at Tura South.

- Day 30: Inspector Merer spends the day with his phyle hauling stones in Tura South; spends the night at Tura South.

Merer Translation: New Cycle Days 1-10

- First Day (New Cycle): The director of 6 Idjer[u] casts off for Heliopolis in a transport boat-iuat to bring us food from Heliopolis while the Elite (stp-sȝ) is in Tura.

- Day 2: Inspector Merer spends the day with his phyle hauling stones in Tura North; spends the night at Tura North.

- Day 3: Inspector Merer casts off from Tura North, sails towards Akhet Khufu loaded with stone.

- Day 4: […] the director of 6 [Idjer]u [comes back] from Heliopolis with 40 sacks-khar and a large measure-heqat of bread-beset while the Elite hauls stones in Tura North.

- Day 5: Inspector Merer spends the day with his phyle loading stones onto the boats-hau of the Elite in Tura North, spends the night at Tura.

- Day 6: Inspector Merer sets sail with a boat of the naval section (gs-dpt) of Ta-ur, going downriver towards Akhet Khufu. Spends the night at Ro-She Khufu.

- Day 7: Sets sail in the morning towards Akhet Khufu, sails towing towards Tura North, spends the night at […].

- Day 8: Sets sail from Ro-She Khufu, sails towards Tura North. Inspector Merer spends the day [with a boat?] of Ta-ur? […].

- Day 9: Sets sail from […] of Khufu […].

- Day 10: […].

New Cycle Days 13-20

- Day 13: […] She-[Khufu] […] spends the night at Tura South.

- Day 14: [… hauling] stones [… spends the night in] Tura South.

- Day 15: Inspector Merer [spends the day] with his [phyle] hauling stones [in Tura] South, spends the night in Tura South.

- Day 16: [Inspector Merer spends the day with] his phyle loading the boat-imu (?) with stone [sails …] downriver, spends the night at She-Khufu.

- Day 17: [Casts off from She-Khufu] in the morning, sails towards Akhet Khufu; [sails … from] Akhet Khufu, spends the night at She-Khufu.

- Day 18: […] sails […] spends the night at Tura.

- Day 19: [Inspector Merer] spends the day [with his phyle] hauling stones in Tura [South?].

- Day 20: [Inspector] Merer spends the day with [his phyle] hauling stones in Tura South (?), loads 5 craft, spends the night at Tura.

Days 21-26

- Day 21: [Inspector] Merer spends the day with his [phyle] loading a transport ship-imu at Tura North, sets sail from Tura in the afternoon.

- Day 22: Spends the night at Ro-She Khufu. In the morning, sets sail from Ro-She Khufu; sails towards Akhet Khufu; spends the night at the Chapels of [Akhet] Khufu.

- Day 23: The director of 10 Hesi spends the day with his naval section in Ro-She Khufu, because a decision to cast off was taken; spends the night at Ro-She Khufu.

- Day 24: Inspector Merer spends the day with his phyle hauling (stones? craft?) with those who are on the register of the Elite, the aper-teams and the noble Ankh-haf, director of Ro-She Khufu.

- Day 25: Inspector Merer spends the day with his team hauling stones in Tura, spends the night at Tura North.

- Day 26: […] sails towards […].

Merer Translation: “x” Days 1-11

- Day x+1: [Sails] downriver […] the bank of the point of She-Khufu.

- Day x+2: […] sails? from Akhet-Khufu […] Ro-She Khufu.

- Day x+3: [… loads?] […Tura] North.

- Day x+4: […] loaded with stone […] Ro-She [Khufu].

- Day x+5: […] Ro-She Khufu […] sails from Akhet-Khufu; spends the night.

- Day x+6: [… sails …] Tura.

- Day x+7: [… hauling?] stones [in Tura North, spends the night at Tura North.

- Day x+8: [Inspector Merer] spends the day with his phyle [hauling] stones in Tura North; spends the night at Tura North.

- Day x+9: […] stones [… Tura] North.

- Day x+10: […] stones [Tu]ra North.

- Day x+11: [Casts off?] in the afternoon […] sails? […].

New Cycle “x” Days 1-8

- Day x+1: […Tura] North […] spends the night there.

- Day x+2: […] sails [… Tura] North, spends the night at Tura North.

- Day x+3: [… loads, hauls] stones […].

- Day x+4: […] spends the night there.

- Day x+5: […] with his phyle loading […] loading a craft.

- Day x+6: […] sails [… Ro-She?] Khufu […].

- Day x+7: […] with his phyle sails […] sleeps at [Ro]-She Khufu.

- Day x+8: […].

Inventing “Proof”

The translation of Merer’s logbook provides a rare and valuable window into the daily operations of a Fourth Dynasty transport crew. Yet it is precisely this narrow scope that undermines the modern claim that the papyri constitute direct proof of the Great Pyramid’s construction. The entries describe movement, provisioning, supervision, and routine maintenance, but they do not describe construction. They do not mention ramps, lifting systems, architectural plans, block placement, or any engineering activity at Giza. The papyrus also doesn’t record the height of the pyramid at the time, the state of the casing, or the progress of any building phase. They do not even specify what the stones were intended for once they reached Akhet Khufu. The papyri are administrative logs, not construction manuals, and their silence on the actual building process is the most important fact in the entire debate.

The Problem of the Late Date in Khufu’s Reign

The absence of construction detail becomes even more significant when considering the date of the documents. The logbook appears to come from the twenty sixth or twenty seventh year of Khufu’s reign. A point at which the Great Pyramid was either complete or very near completion according to mainstream chronology. If the monument already stood in its final form, then Merer’s shipments cannot reasonably count as core blocks or foundational elements. They could just as easily have been casing stones, causeway stones, valley temple stones, or materials for unrelated royal projects. The papyri never clarify this.

They simply record that the boats were loaded with stone and sailed to Akhet Khufu. The assumption that these stones must relate to the pyramid’s primary construction is a modern projection, not a conclusion supported by the text.

Why the Find Location Undermines the “Smoking Gun” Narrative

The location of the papyri’s discovery further complicates the narrative. Wadi el Jarf is a Red Sea port more than two hundred kilometers from Giza. It was used primarily for expeditions to Sinai. It is not a Nile port, not a Giza administrative center, and not a logical archive for the central records of the largest construction project in the Old Kingdom.

The papyri turned up discarded in a storage gallery, not preserved in any official archive. If these documents truly served as the definitive record of the pyramid’s construction, their abandonment at a remote coastal facility makes little sense, especially when officials in Memphis or Giza would have stored such records locally. Their presence at Wadi el Jarf makes perfect sense if they were routine logs belonging to a transport crew that operated between multiple sites. But, it makes little sense if they were the key administrative documents of the pyramid project.

Environmental Evidence Points to Local Transport, Not Red Sea Oversight

Environmental evidence from the PNAS study published in 2022 adds another layer of context that weakens the idea that Wadi el‑Jarf held central construction records. That study reconstructs a now‑vanished Nile tributary, the Khufu branch, which once flowed close to the Giza plateau and supported a local harbor system directly at the site. This makes long‑distance administrative oversight from a remote Red Sea port unnecessary. The papyri describe movement between Tura, She Khufu, Ro‑She Khufu, and Akhet‑Khufu, all of which lie along this inland water network.

Complementing this, a 2024 Nature Communications study identifies the much larger Ahramat Branch, a paleo‑channel that once ran along the entire pyramid field from Lisht to Giza. Together, these environmental reconstructions show that Old Kingdom logistics were anchored in a dense, local Nile‑based transport system. Nothing in the environmental data suggests that Wadi el‑Jarf played a central role in the pyramid’s construction logistics. Instead, the evidence reinforces the idea that the papyri reflect only one small part of a much broader and more localized transport network.

The Stones Are Never Identified by Type or Purpose

The modern claim that the papyri prove the construction of the Great Pyramid often rests on the assumption that the stones Merer transported must have been casing stones for the monument. Yet the logbook never identifies the stones by type, size, or purpose. It does not distinguish between fine Tura limestone and other varieties. The log never states whether the stones were destined for the pyramid, the temples, the harbor, or any other structure. Scholars label them as casing stones only because the mainstream narrative assumes casing transport occurred during this period. This circular reasoning transforms expectation into evidence, and it is precisely the kind of interpretive leap that a critical examination must resist.

The Block‑Count Narrative Is an Inference, Not a Textual Fact

The same pattern appears in the widely repeated claim that Merer’s team transported thirty blocks of two to three tons per trip. This figure is not found in the papyri. It is an estimate derived from assumptions about boat capacity, block weight, and trip frequency. While these assumptions are not unreasonable, they are not textual facts. They are modern reconstructions designed to fit a broader construction timeline. When scholars present these estimates as if they were explicit statements from the logbook, they inadvertently inflate the evidentiary power of the papyri. The logbook does not quantify loads, does not describe the dimensions of the boats, and does not specify the number of blocks carried. It simply records that the boats were loaded with stone. Everything beyond that is interpretation.

Administrative Records Are Not Construction Records

The administrative nature of the papyri also deserves emphasis. Merer records provisioning, supervision, and routine tasks such as dyke maintenance. These entries reveal a well organized transport system, but they do not reveal anything about the engineering of the pyramid. They show that the Egyptians moved stone by boat, maintained waterways, and coordinated teams. None of this is surprising, and none of it demonstrates how the pyramid was built. The papyri show that Merer’s team delivered stone to Akhet‑Khufu, but they never reveal what happened to the stone once it arrived.Without that missing link, the documents cannot serve as direct evidence of construction.

The Ankhhaf Argument Does Not Resolve the Ambiguity

Even the references to Ankh haf, often cited as proof of a direct connection to the pyramid project, do not resolve the ambiguity. Ankh haf oversaw many royal works, not only the Great Pyramid. His presence in the papyri indicates that Merer’s team operated under high level supervision. But, it does not specify which project their cargo supported. The assumption that Ankh haf’s involvement automatically ties the papyri to the pyramid’s construction is another example of reading the text through the lens of expectation rather than evidence.

A Valuable Document, but Not the Proof It Is Claimed to Be

Taken together, these issues reveal a consistent pattern. The Papyrus of Merer is an authentic and invaluable document, but its evidentiary scope is limited. It records transport, not construction, it describes movement, not engineering. It documents logistics, not architecture. The modern tendency to treat it as definitive proof of the Great Pyramid’s construction relies on assumptions. Ones that extend far beyond what the text actually says. When the papyri are read strictly on their own terms, without the weight of modern expectations, they provide insight into the operations of a transport crew in the late reign of Khufu. But, they do not resolve the question of how the Great Pyramid was built.

Conclusion

The value of the papyri lies in their authenticity and their detail, not in their ability to settle debates they were never intended to address. They illuminate the logistical world of the Fourth Dynasty, but they do not serve as a blueprint for the pyramid. By recognizing the limits of what the papyri can tell us, we avoid the trap of overstating their significance and allow them to stand as they are. A remarkable but incomplete record of a single team’s activity within a much larger and still only partially understood royal landscape. The Papyrus of Merer enriches our understanding of Khufu’s era, but it does not close the case on the construction of the Great Pyramid. It remains a piece of the puzzle, not the solution.

For more in depth examination of Ancient Egypt check out Taposiris Magna: Search for Cleopatra’s Tomb