Megalithic Structures Rewrite Pre-Portuguese Azores Discoveries

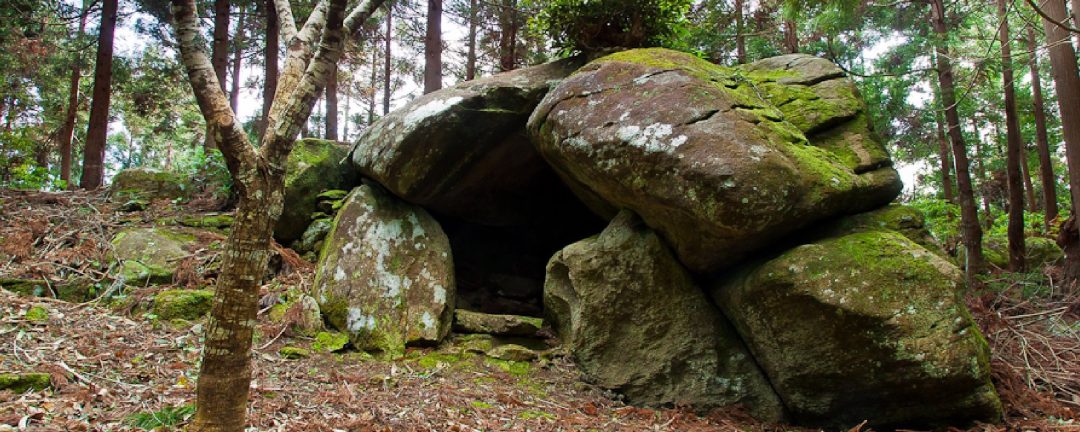

The discovery of megalithic structures on Terceira Island has sparked debate about early human presence in the Azores. These megaliths resemble passage and portal tombs found in Western Europe, challenging claims that the islands were uninhabited before Portuguese arrival. Their existence raises questions about ancient human movement and maritime skill across vast ocean distances in prehistoric times

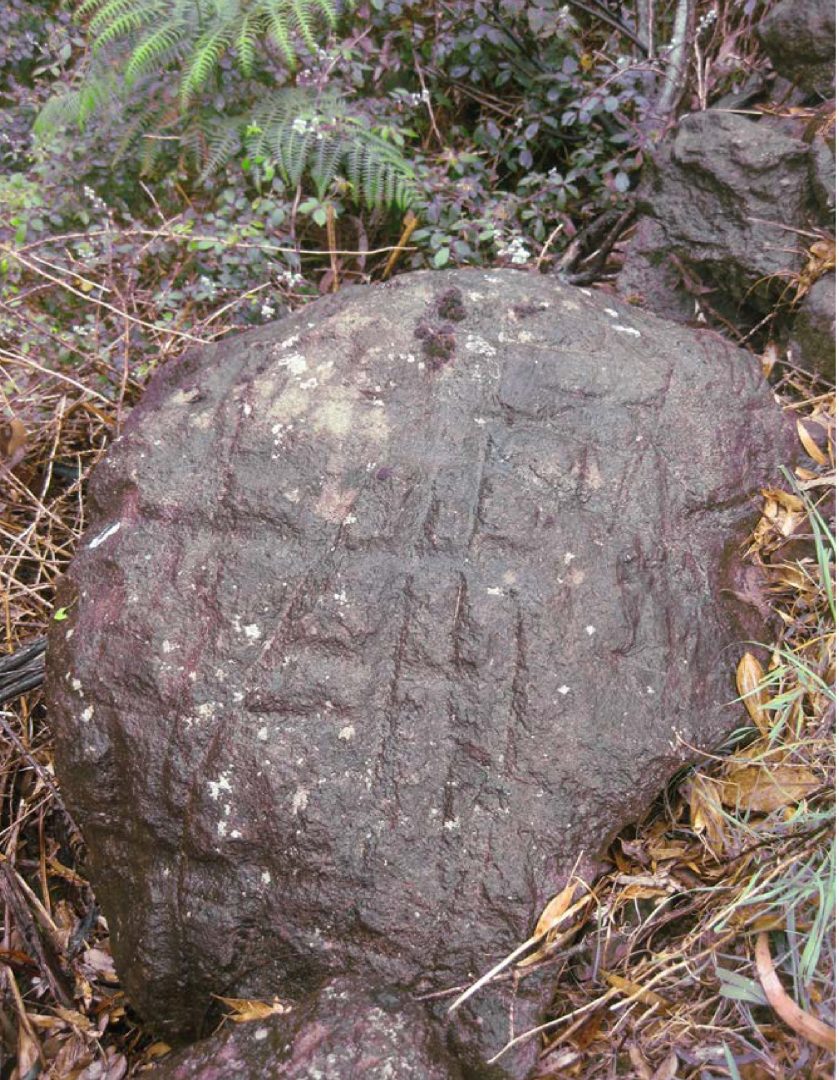

Multiple bowls carved in the same stone, as noted by Nigel (2000) for Irish bullauns, echo findings here.

Commentary

Exploring Azores archaeological mysteries places us at history’s edge, gazing into a past etched in stone and silence. Grota do Medo on Terceira Island reveals structures resembling those from Scotland to southern Spain, linking to the Atlantic façade. These stones may reflect cultural exchange or parallel development, possibly dating to the Neolithic, Chalcolithic, or Bronze Age.

Ancient Maritime Azores: A New Narrative

Structures similar to passage graves or tombs, made of massive stones with burial chambers covered by earth, dot the landscape. The implications of these discoveries are profound. Since these megalithic Azores history markers undeniably predate the Portuguese discovery, they open a Pandora’s box of questions about ancient maritime prowess. Paleolithic ocean levels were lower, suggesting landmasses might have been closer or islands more accessible, facilitating human migration or exploration far earlier than considered. Anchors found on Azores beaches—relics hinting at navigational activities—further fuel this ancient maritime Azores hypothesis.

The narrative of these islands as a 15th-century find is now under scrutiny, not as an academic exercise but as a revaluation of human history. These Neolithic Azores structures suggest humans might have navigated the Atlantic, driven by curiosity, trade, or ritual, echoing Bronze Age journeys where the sea was a pathway, not a barrier.

Grota do Medo Secrets: Passage Tombs and Beyond

At the Grota do Medo site, megalithic construction with similarities to European passage tombs emerges. As we embark on this journey of rediscovery, humility is key—answers lie buried under layers of time and earth. These findings demand a multidisciplinary approach, where archaeology, anthropology, and history converge to unravel our past. The Azores, once a blank slate, now whisper of ancient stories, voyages, and cultures that left their mark long before we named them.

Engravings in capstones with bowls atop, akin to Irish wedge-shaped gallery graves, dot Terceira Island.

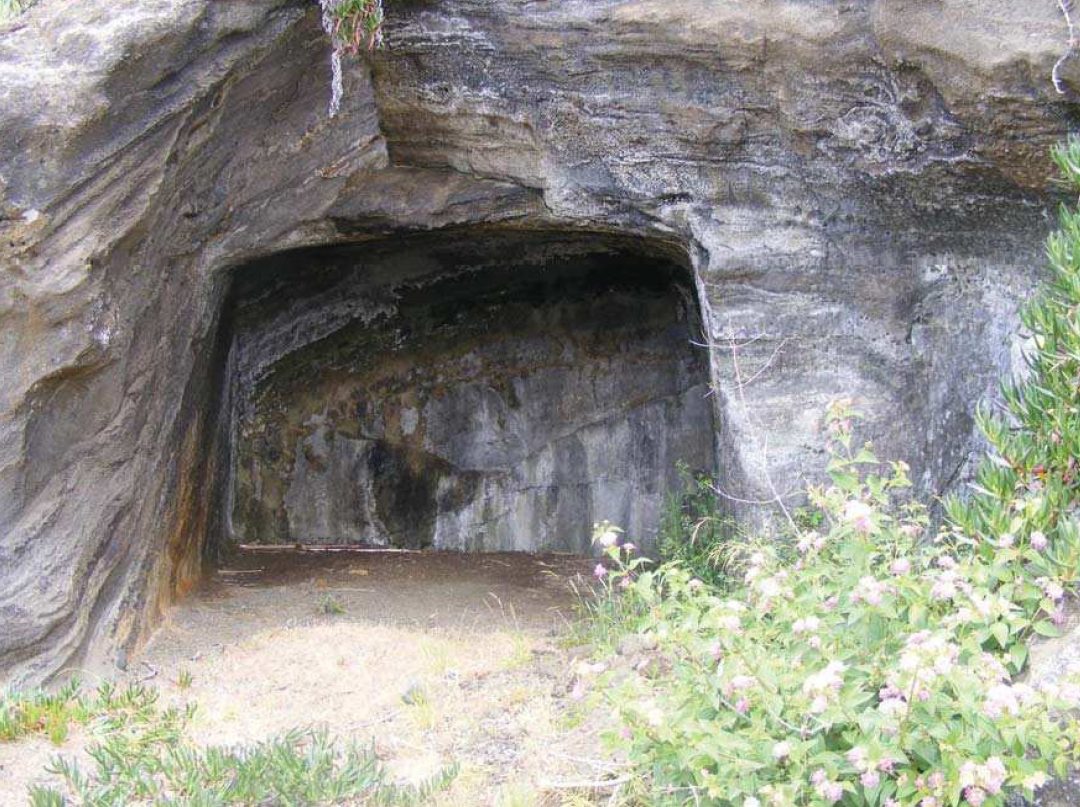

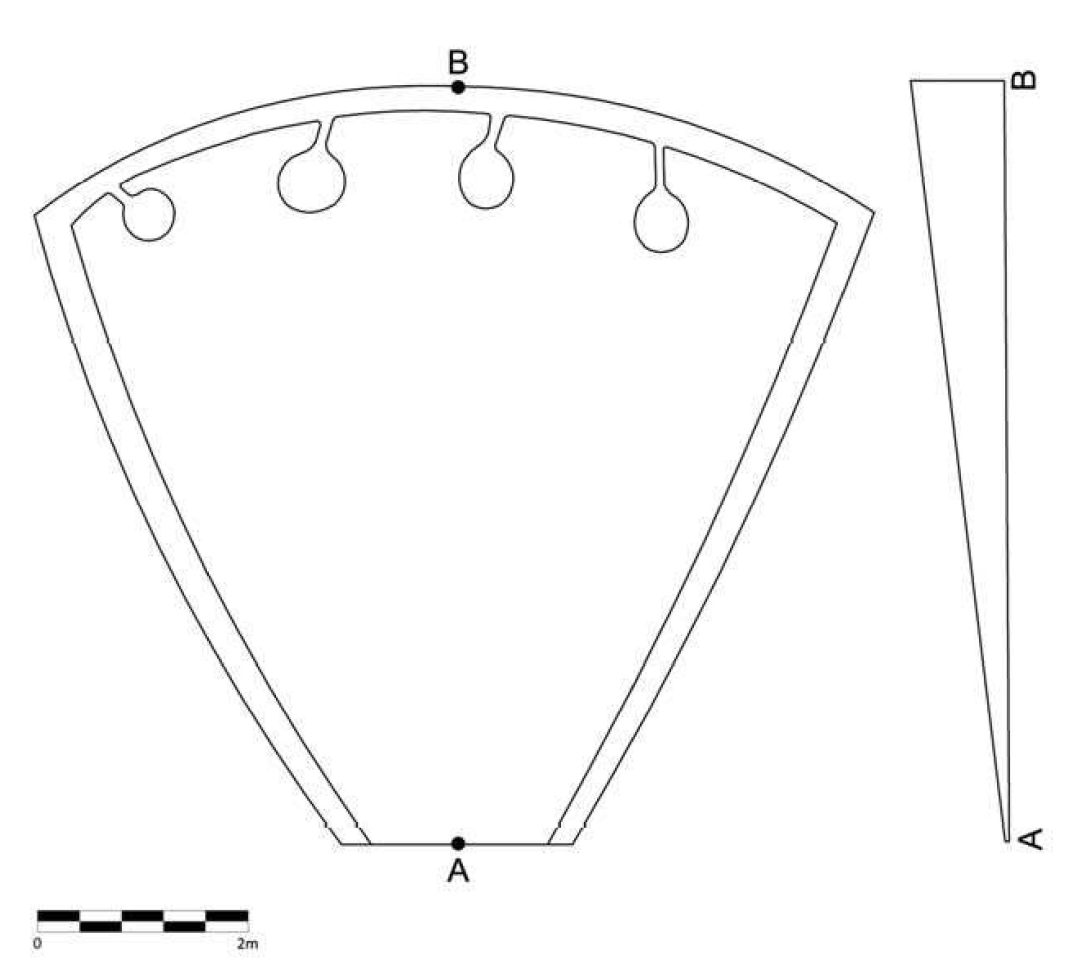

The Azores unveil their secrets through stone’s silent testimony. Among the most compelling Grota do Medo secrets are structures reminiscent of Western Europe’s passage tombs. These aren’t coincidences but bear hallmarks of architectural and symbolic sophistication. As I often say, Coincidence Takes Planning. Picture two structures: one with a southeast-facing entrance, embodying a passage tomb stretching from Scotland to Spain; the other, larger, with a northern entrance, cementing ties to ancient European constructs. Both, crafted with stones over two tons, suggest a knowledge of balance belying the notion of the Azores as a cultural void.

Terceira Island Megaliths: Construction and Culture

Megalithic structures with similarities to portal tombs reveal intent beyond mere stone placement. Worked stones, crafted corridors, and high-ground placement echo Neolithic and Bronze Age practices across the Atlantic façade. This raises questions about knowledge transmission or parallel architectural evolution across vast distances. These Terceira Island megaliths aren’t just curiosities—they’re cultural artefacts, hinting at a society with stable resources, social structure, and a belief system honoring the dead through enduring monuments.

Trachyte with typical cup-marks at Grota do Medo speaks further. The landscape—high points of Pico do Espigão—dominates island and sea, suggesting practical and ceremonial roles. Tomb orientations might tie to astronomical observations or rituals, a common megalithic theme.

Azores Rock Art History: A Deeper Connection

Four structures resembling Irish portal tombs, with east-facing entrances and corbelled chambers, add layers to this Azores rock art history. Their water association suggests a bond with nature, where stone and water dance in life, death, and rebirth. Rock art at Grota do Medo, akin to European finds, ties the Azores to an ancient conversation across time and space—a dialogue of ingenuity, spirituality, and meaning.

The Azores, jewels in the Atlantic, were long seen as the last frontier of Western discovery. Yet, these Bronze Age Azores evidence—megaliths, anchors, obsidian—suggests they were waypoints in ancient maritime journeys, far predating Portuguese explorers.

Ancient Navigation and Trade in the Azores

The enigma of ancient navigation unfolds. The distance from Portugal to Terceira Island is vast, yet Bronze Age boats like the Dover Boat show such feats were possible. Anchors on Azorean beaches—silent witnesses—imply the Azores were a known stop on ancient routes. Obsidian, not native but found on Terceira, hints at trade or exchange, linking to Neolithic and Bronze Age networks via the Santa Bárbara stratovolcano.

Rock art, like a Scandinavian Bronze Age boat engraving on an Irish-style wedge tomb, narrates a maritime heritage where the sea bridged worlds. These pre-Portuguese Azores discoveries challenge the 15th-century origin story, suggesting exploration, trade, or sacred quests drove ancient voyages.

A Vibrant Prehistoric Azores

Canals

Small canals, basins, and chairs carved from outcrops dot Corvo Island’s rocks. Accepting a prehistoric Azores presence—perhaps Bronze Age, Nordic, then Portuguese—forces us to rethink ancient capabilities and interconnectedness. This isn’t just about timelines; it’s about the human spirit’s drive to explore, connect, and mark the earth. The Azores whisper of continuous occupations across cultures, ending with events like the 4000BC shift I’ve detailed elsewhere.

The Azores’ megalithic structures belong to an ancient conversation across time, revealing human ingenuity, spirituality, and cultural meaning. This discovery challenges history and urges us to explore a vibrant past where the Azores played an active global role.

Set like jewels in the Atlantic, the Azores were long seen as the last frontier of Western human discovery. Yet, megalithic structures and artefacts suggest these islands served as waypoints in ancient maritime journeys—long before Portuguese explorers arrived.

Navigation

Let’s delve into the enigma of ancient navigation. The distance from mainland Portugal to Terceira Island is considerable, yet not beyond the reach of Bronze Age seafarers. Archaeological evidence from Europe, such as the middle Bronze Age Dover Boat, indicates that complex vessel construction was within the technological grasp of these ancient societies. If such boats could traverse the English Channel, why not the Atlantic to the Azores?

The hypothesis of ancient transatlantic voyages gains further credibility when considering the anchors found on Azorean beaches. These anchors, silent witnesses to maritime activity, suggest that vessels capable of such journeys might have plied these waters long before recorded history. While their origins and ages remain speculative, their presence implies that the Azores were not just a discovery waiting to happen but potentially a known stop on ancient maritime routes.

Evidence

Obsidian, a material not native to the Azores but found on Terceira Island, hints at trade or cultural exchange. This volcanic glass, prized in prehistoric times for its sharpness, was often traded over vast distances. The “Santa Bárbara” stratovolcano on Terceira could have been a source or destination for such materials, linking the island to the broader networks of Neolithic and Bronze Age commerce.

Moreover, the rock art, particularly the engraving resembling a Scandinavian Bronze Age boat on a structure similar to an Irish wedge tomb, pushes the boundaries of our understanding. This imagery speaks of a maritime heritage, where the sea was a conduit for culture, ideas, and people. It’s as if the stone itself narrates tales of seafaring ancestors who saw the ocean not as a barrier but as a bridge between worlds.

The incorporation of these findings into our historical understanding challenges the notion that the Azores were uninhabited or unknown before the 15th century. This narrative proposes that humans crossed the ocean not merely to survive, but to explore, trade, settle new lands, or establish sacred sites.

Implications

The implications here are vast. By accepting the possibility that humans reached the Azores in prehistory, we must reconsider ancient capabilities and cultural interconnectedness. During the Bronze Age, the Nords and later the Portuguese may have reached the Azores, reshaping historical assumptions. This opens avenues for research into navigation, ritual seafaring, and pre-Portuguese cultural landscapes in the Azores. Evidence suggests continuous occupation by different cultures across distinct time periods.

I believe the first occupation ended with the 4000 BC event, as described in my article, paper, and video. This is not just about proving or disproving a timeline—it’s about recognizing the human spirit’s drive to explore and connect. Humans trade, leave marks, and build meaning into landscapes. Whether isolated or networked, these structures reflect a time when the ocean shaped human life, culture, and identity.

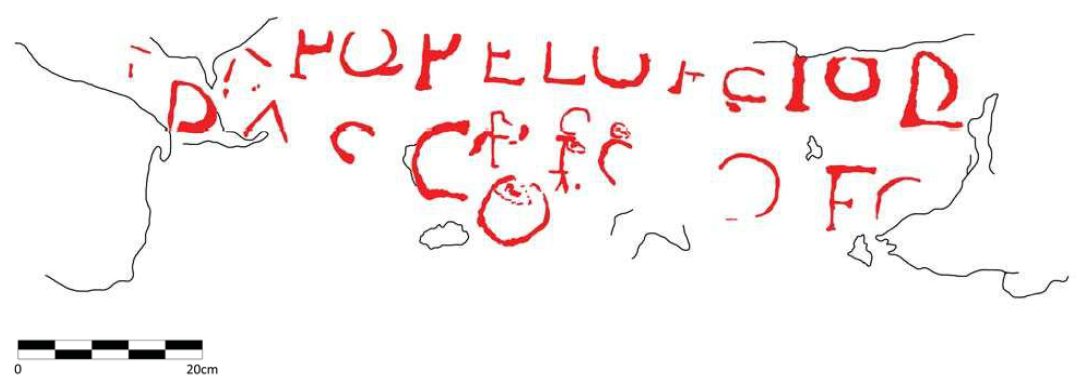

The silent stones of the Azores whisper stories through engravings, paintings, and carvings—a language of lines, dots, and symbols. This symbolic language transcends time and speaks to cultural memory embedded in the landscape. Rock art at Grota do Medo on Terceira Island is not decorative—it reflects ritualistic, cultural, or astronomical practices. We will only understand its meaning when historians accept its relevance and allow new studies to explore its implications.

Rock Art

The rock art here is diverse, ranging from simple cup-marks to more intricate designs. These cup-marks are small depressions carved into stone, common in Atlantic European prehistory and linked to Bronze Age practices. They often relate to religious rituals or celestial observations across ancient cultures. Grota do Medo shows many cup-marks, suggesting continuity or parallels with rock art in Scotland, Ireland, and the Iberian Peninsula.

Each cup-mark or stroke may represent a star, a ritual drop of water, or a sign of human presence. The metaphor of water and stone in the Azores reflects Neolithic Irish practices involving bowls or bullauns placed near water. This association suggests a spiritual or practical link to nature, where water gives life and stone preserves memory.

The island’s rock art includes complex motifs, such as a carving interpreted as a Bronze Age boat. This carving suggests a deep connection to maritime culture and ancient seafaring traditions. Other engravings imply the sea was central to cultural and spiritual life, not just a physical boundary. These people may have viewed themselves as part of a broader oceanic community. Boats could have symbolized journeys, trade, or even the soul’s voyage to the afterlife.

Local Influence

However, the rock art of the Azores doesn’t fit neatly into any known European sequence. There are elements here that are unique or at least not clearly paralleled elsewhere. The abstract schemes and geometric designs, like the semi-circular and circular inscriptions, hint at a local adaptation or evolution of these symbols, possibly for astronomical, territorial, or ritualistic purposes.

One particularly intriguing example is the rock art that resembles a chessboard, a design linked to the Copper Age in parts of Europe. This suggests not only artistic but also cultural exchanges or similar cognitive developments across different regions, perhaps through maritime contacts or migrations.

Not as Simple as it May Seem

Yet, the meaning of these symbols remains elusive, cloaked in the mists of time and culture. Were these markings a form of communication, a record of celestial events, or something else entirely? Their enigmatic nature points to a human pre-Portuguese presence in the Azores, one that was culturally rich and possibly connected to the broader tapestry of Atlantic Europe.

The rock art reshapes our view of the Azores—not as a cultural backwater, but part of an interconnected ancient world. Art, science, and spirituality converged here, challenging the idea that history began with Portuguese arrival in the 15th century. We must decode these stone-carved messages and reconstruct the story of a people whose origins predate accepted historical timelines.

In the Azores, especially at Grota do Medo, a symbolic relationship between water and stone begins to emerge. This theme echoes ancient Atlantic cultures and appears across multiple archaeological contexts. The connection seems deliberate, forming part of the island’s cultural and spiritual prehistoric landscape.

Grota do Medo

The structures at Grota do Medo feature bowls and depressions positioned to collect rainwater and direct it through channels. Water pools in these stone containers, suggesting intentional design and symbolic function. Similar practices appear across Neolithic and Bronze Age European sites, indicating ritualistic or symbolic water use. Ancient societies viewed water as sacred—representing life, purification, and the passage between earthly existence and the divine.

Consider the bullauns, those water-filled depressions found in Ireland, which have parallels in the Azorean bowls. In Ireland, these bowls may link to Christian practices. Azorean counterparts seem to serve a different, possibly older, ceremonial or symbolic purpose. Bowls on Terceira Island sit where agricultural or domestic use is impractical, yet they fill with rainwater. This suggests a ritual where water from the sky sanctifies stone structures. Such practices may link celestial, terrestrial, and human realms in symbolic harmony.

This interplay of water and stone is further emphasized by the placement of these sites. At Grota do Medo, one can stand on the hill and see the sea, rivers, outcrops, and the island’s highest mountain, a landscape that seems designed to be experienced in relation to water. The structures themselves are often near cliffs or high points, where the sound and sight of the ocean might mingle with the ritualistic use of water, creating a holistic experience of the environment.

Symbolism

The symbolism here is rich. Water represents change, life, and time’s passage. Stone symbolizes permanence, memory, and ancestral presence. Together, they form a dialogue about existence and life’s cycle. This connection links humans to the cosmos through natural elements. It’s not just survival—it’s spiritual sustenance rooted in elemental relationships. Ancient Azoreans may have embraced a cosmology shaped by nature’s forces and rhythms.

These practices imply a sophisticated understanding of the landscape and its spiritual significance to the ancient Azorean community. Every element—from peaks to watercourses—played a role in their cultural and spiritual life. Structure orientation, astrological alignments, and water interaction suggest a culture deeply attuned to nature’s rhythms. This mirrors traditions found in ancient Ireland and Scotland.

In this context, the Azores appear less isolated and more connected to a broader cultural canvas of meaning. Water and stone are not just materials—they serve as conduits for the spiritual life of ancient Azorean people. This culture viewed earth and sky as an interconnected whole, not separate realms. Each drop of rain and carved stone tells a story of human effort to understand and harmonize with the world.

Controversy

Revelations from the Azores have stirred an academic tempest, challenging historical and cultural foundations of this Atlantic archipelago. The traditional narrative claims Portuguese explorers discovered the Azores in the 15th century. That story is now under siege. Silent stones speak of a time long before recorded history.

The scientific community faces a conundrum. On one hand, the lack of dated artefacts or clear historical references makes it difficult to place these structures definitively in time. The absence of pottery or tools that could be carbon-dated adds to the mystery. Yet, the similarities with European megalithic structures, the rock art, and the strategic placement of these sites suggest a cultural sophistication that could not have been spontaneous or isolated.

This debate concerns more than construction dates—it challenges our understanding of migration, navigation, and cultural exchange in ancient history. Megalithic structures and rock art in the Azores dispute the idea of the ocean as a prehistoric barrier. Evidence suggests ancient peoples had knowledge, means, and motivation to cross vast distances. They may have followed celestial or meteorological patterns now lost to us.

Culturally, these findings force us to reconsider the narrative of the Azores as a “new world” discovered by Europeans. If people visited or inhabited these islands during the Neolithic or Bronze Age, they joined an ancient cultural network—possibly a crossroads where traditions met, mingled, or evolved on their own. This challenges the long-held view of Azorean heritage, which has focused almost entirely on its Portuguese colonial past.

Bigger Picture

The debate extends beyond academia into the realms of identity, heritage, and tourism. If the Azores have a pre-Portuguese history, how does this reshape the cultural identity of its inhabitants? Does it alter the storytelling of the islands, their place in global history, and how they market themselves to the world?

Scientifically, the need for further research is evident. A multidisciplinary approach is required, involving archaeologists, historians, anthropologists, geologists, Sound and astronomy experts and perhaps even linguists to decode the cultural artefacts and environmental data. Excavations, new dating methods, and comparative studies with other Atlantic sites could shed light on the timeline and cultural affiliations of these structures. The problem is that would be recognizing these sites and what they mean to the History Books.

All of this is quite in tune with the times, for this causes a cultural debate about how we view history. Are we willing to expand our understanding beyond written records? Can we embrace a narrative where the Azores were not just a place of exile or refuge for those fleeing the Inquisition but a land with its own ancient stories, potentially as old as the European megalithic tradition?

Implications

The implications are vast. If we accept pre-Portuguese megalithic presence, we must ask how and why these peoples arrived. What did they seek? What did they leave behind? This exploration may reveal how cultures form, interact, and evolve through dynamic exchanges—not isolation. The debate challenges us to look beyond known history. It invites us to wonder about unknown stories buried beneath our feet.

The journey through the ancient Azores reveals layers of time and a history more profound than previously imagined. Megalithic constructions, rock art, and symbolic water-stone interplay on Terceira Island reshape our understanding of the landscape. This place was not simply discovered—it may have been rediscovered by modern humans after long cultural dormancy.

This narrative reshapes how we understand the Azores—not as a blank canvas for Portuguese history, but as a landscape inscribed with its own ancient, still-untranslated script. The implications run deep: the Azores did not stand apart from the cultural exchanges that shaped the Atlantic façade. Instead, they played a role in a grand human story of expansion across the planet, where globalization began not 600 years ago, but in time immemorial.

A Crossroads

The scientific and cultural implications of these findings are clear. We now stand at a crossroads, compelled to rewrite history—or at least expand it to include these new chapters. The long-held belief that the islands remained untouched until the last millennium no longer holds. Evidence shows that humans may have walked these lands when ocean levels were lower, and ancient mariners could have treated the Azores as a stepping stone or sanctuary

The anchors on the beaches, the obsidian hinting at trade or visitation, and the structures themselves all point to a prehistory of the Azores that was vibrant and connected. This calls for a new kind of archaeological endeavour, one that is interdisciplinary, that embraces both the hard sciences for dating and analysis and the humanities for interpreting the cultural significance of these findings.

There is humility in this discovery—a reminder that historical understanding evolves with new evidence. Being wrong is a privilege, not a failure. It means we are learning, not just repeating unproven memories. The Azores islands, once silent, now speak through stone. They invite us to listen, question, explore, and connect the dots of human history across the Atlantic.

Conclusion

In conclusion, these findings do more than just revise a timeline; they enrich the cultural heritage of the Azores, providing its people with a deeper sense of place in the world’s history. They remind us of the human spirit’s resilience and curiosity, of our ancestors’ ability to navigate not just the waters but the very stars above them. The Azores become not just an archipelago but a symbol of human capability that is far more remote than previously believed, a testament to the idea that our stories are far older, far more mysterious, and infinitely more connected than we might have ever guessed. As we continue to unearth these silent witnesses, we are reminded that every stone, every carving, holds a part of our collective memory, waiting to be told.

All images are from the papers to be found in this article Bibliography, and a rare BBC Documentary, here presented under fair use for education purposes only.

Bibliography: