In the shadowed annals of history, where the echoes of ancient civilizations whisper through time, the Codex Grolier offers a glimpse into the Maya’s forgotten past. This enigmatic relic of the Maya, a people whose brilliance in astronomy, mathematics, and art. These once shone across Mesoamerica, with this codex to rank among just four known surviving Maya codices. It remains the only one still gracing the Americas. Now officially named the Códice Maya de México, its journey was not a conventional one. From a hidden cave to a vault in Mexico City is a tale of mystery, controversy, and eventual validation. One revealing a world nearly erased by conquest.

A Glimpse into the Maya’s Forgotten Past: The Discovery

The Codex Grolier surfaced in the 1960s with circumstances rivaling any adventure tale. It all starts with a Mexican collector named Josué Sáenz. He claimed he was contacted by looters who offered to show him a trove of Maya artifacts. In order to do that, he agreed to fly to a secret location without asking questions. Sáenz recounted being taken in a light plane to a remote airstrip in the foothills of the Sierra de Chiapas.

This is near Tortuguero in Tabasco state, but the plane’s compass has covered by a cloth to obscure the destination. Looters showed Sáenz a collection of items they allegedly found in a dry cave. These include: a mosaic mask, a wooden box bearing the glyph-emblem of Tortuguero. Also a sacrificial knife with a handle shaped like a clenched fist, a child’s sandal, a piece of rope. Finally there was also a pictographic manuscript, the Codex Grolier. A first Glimpse into this treasure of Maya’s forgotten past.

The Codex Flies Home

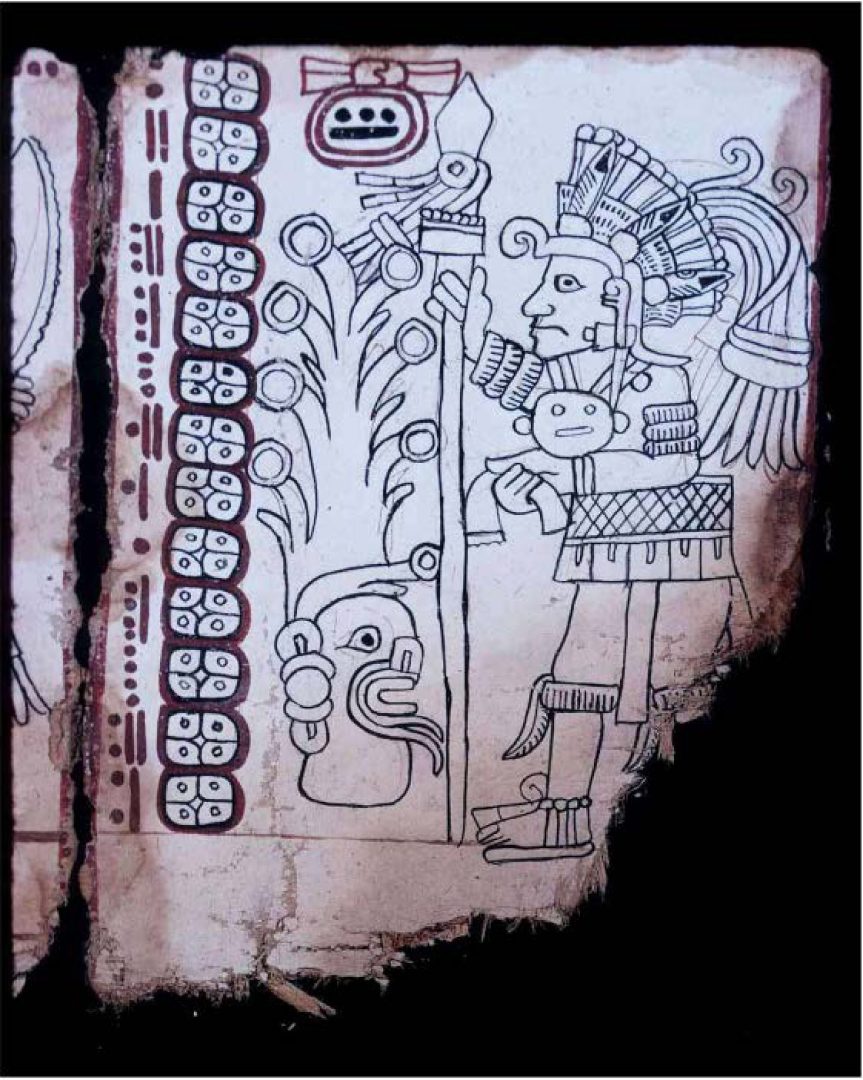

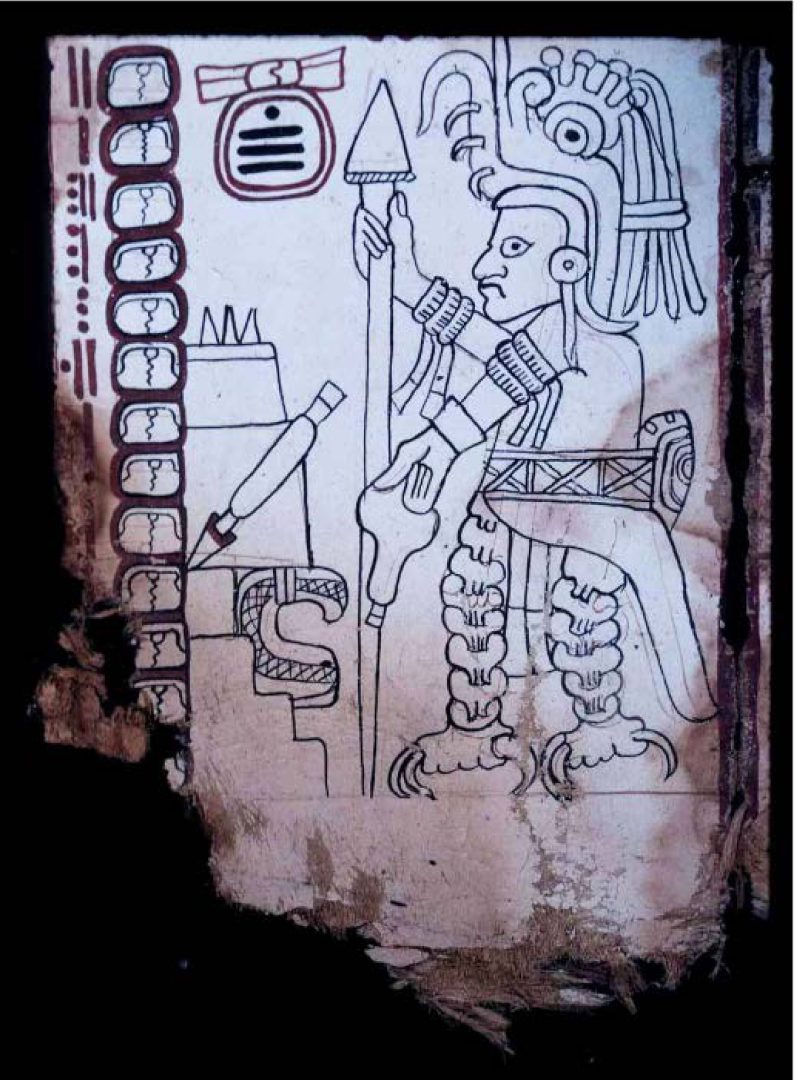

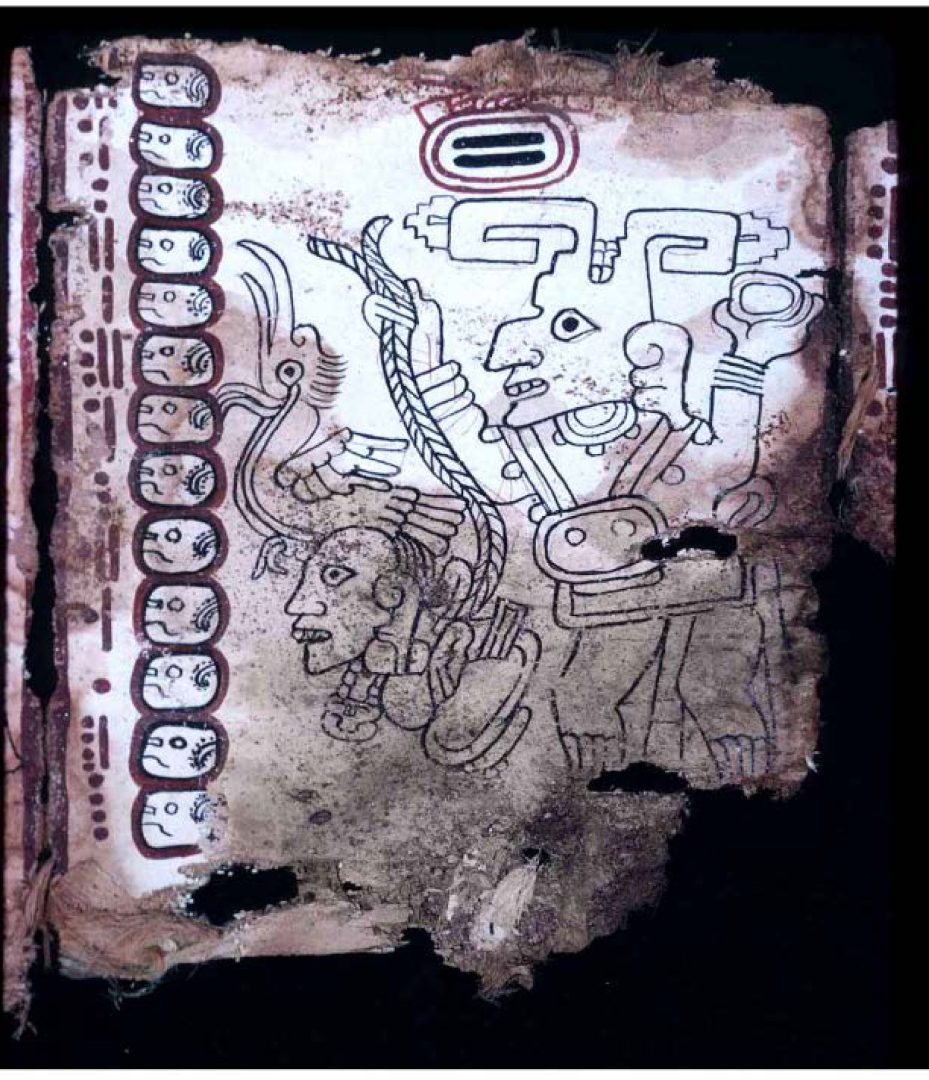

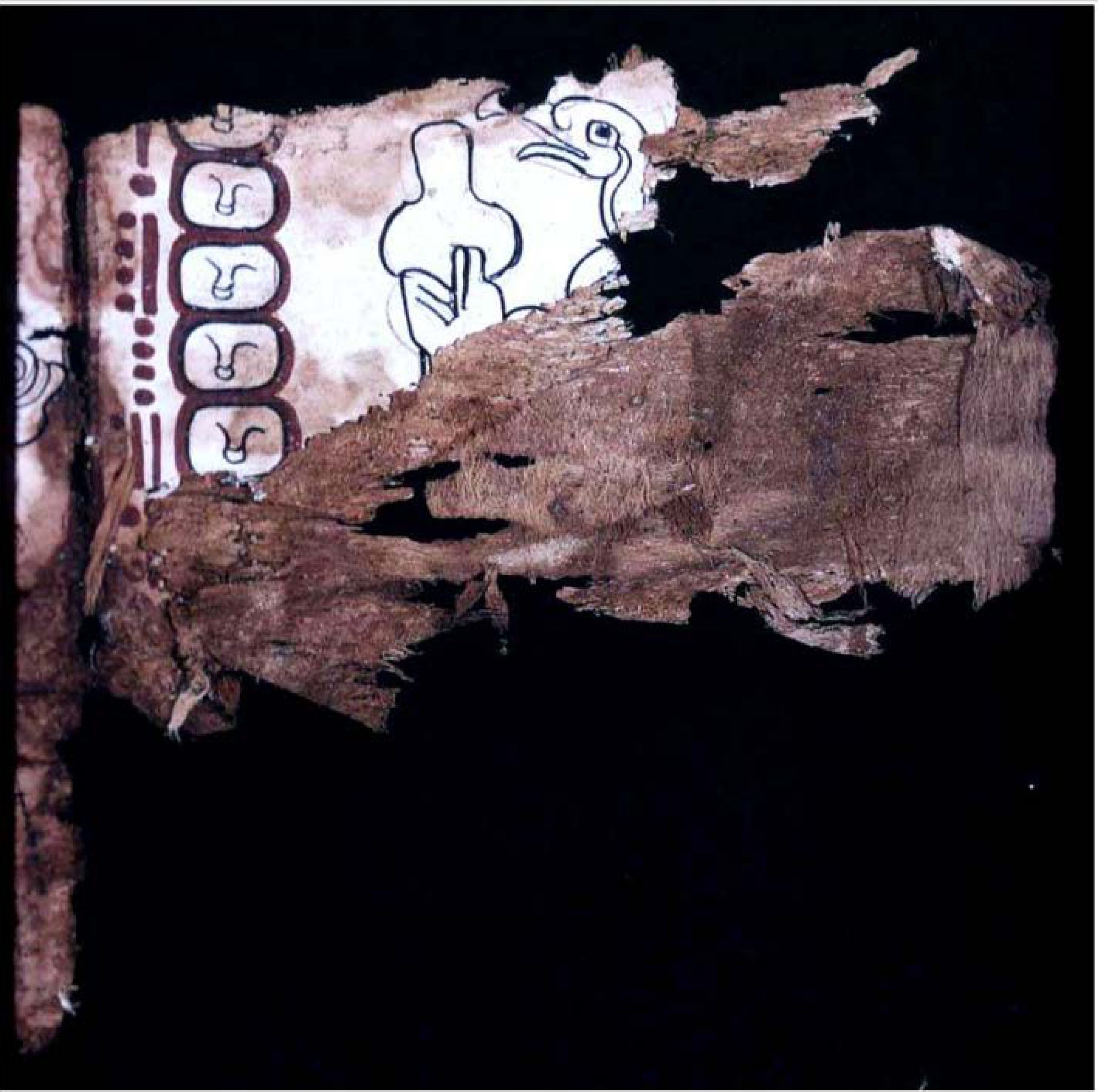

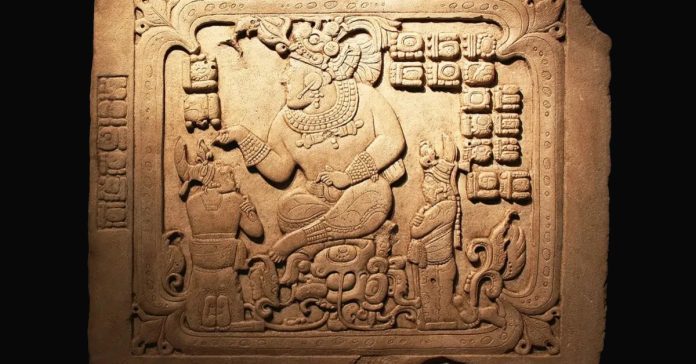

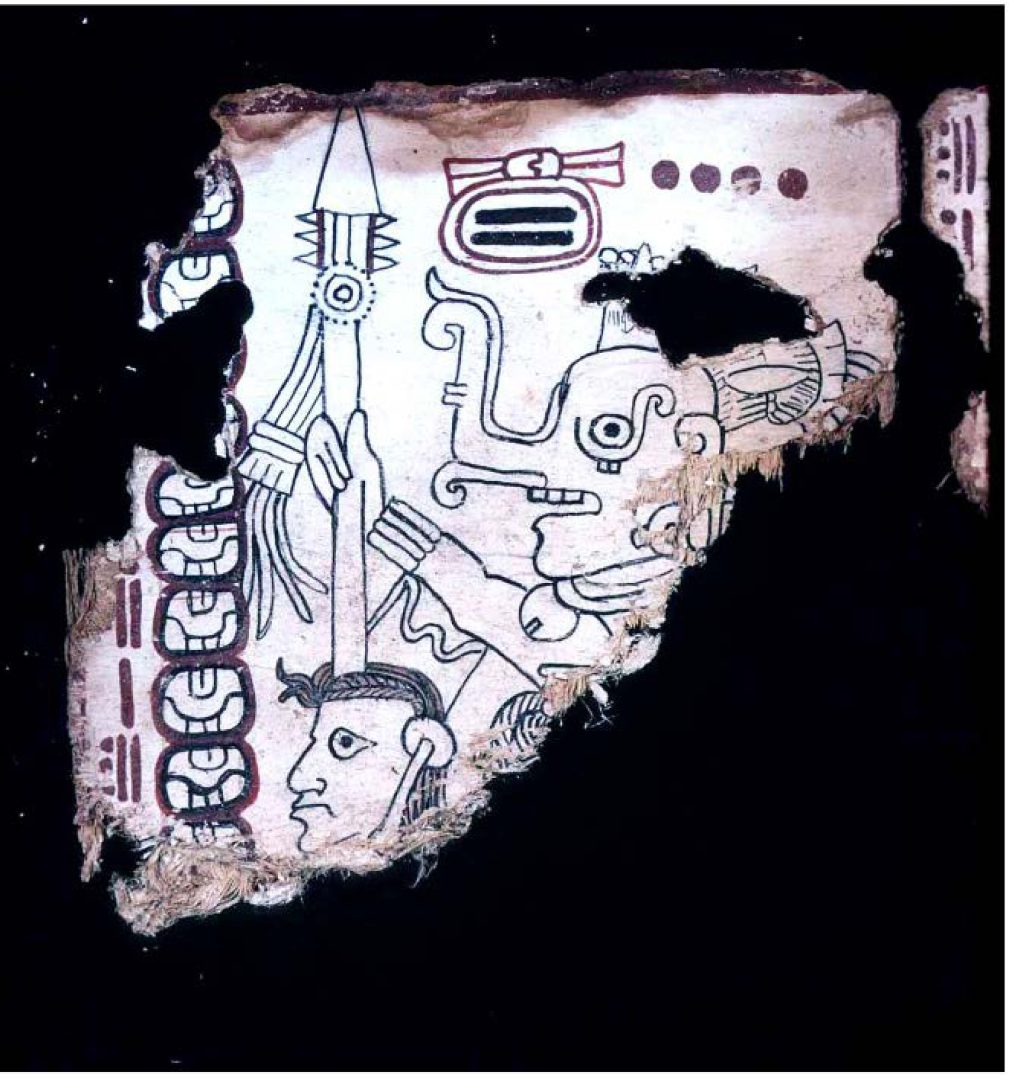

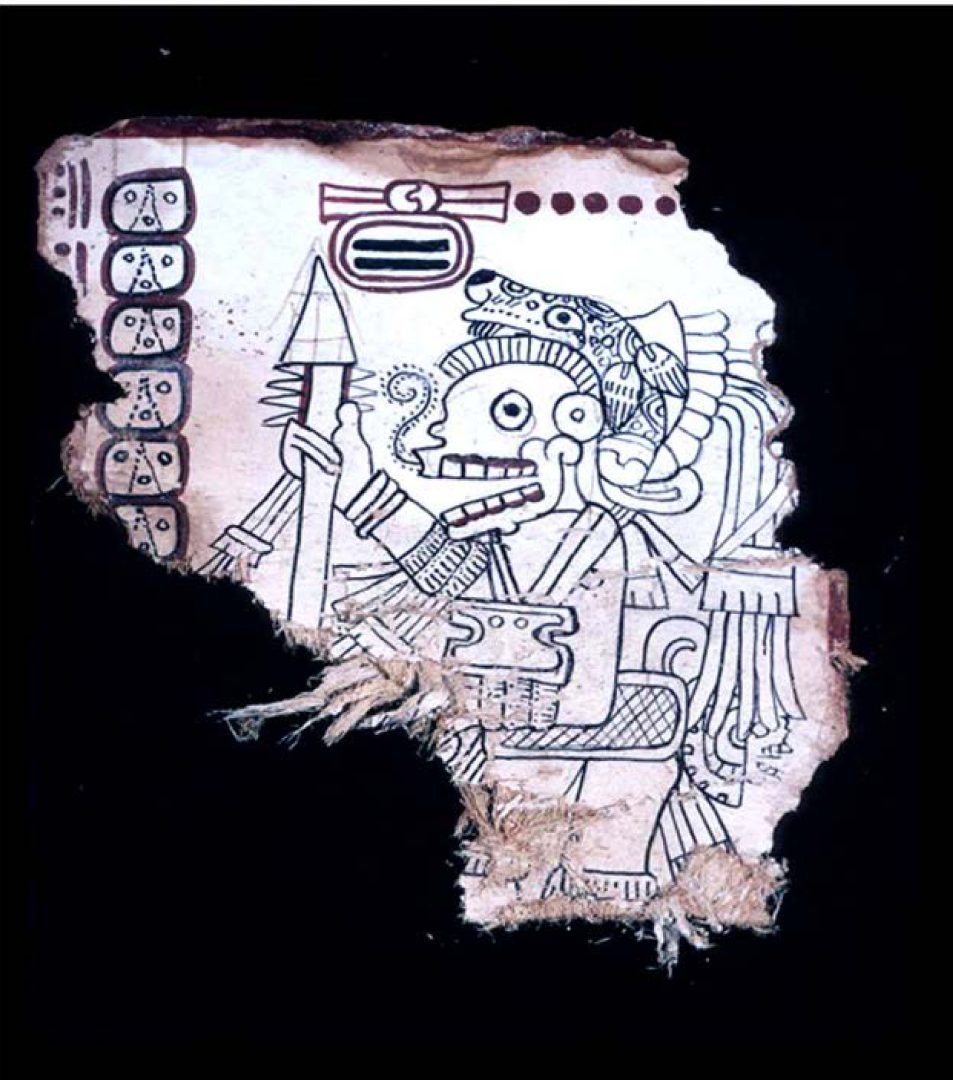

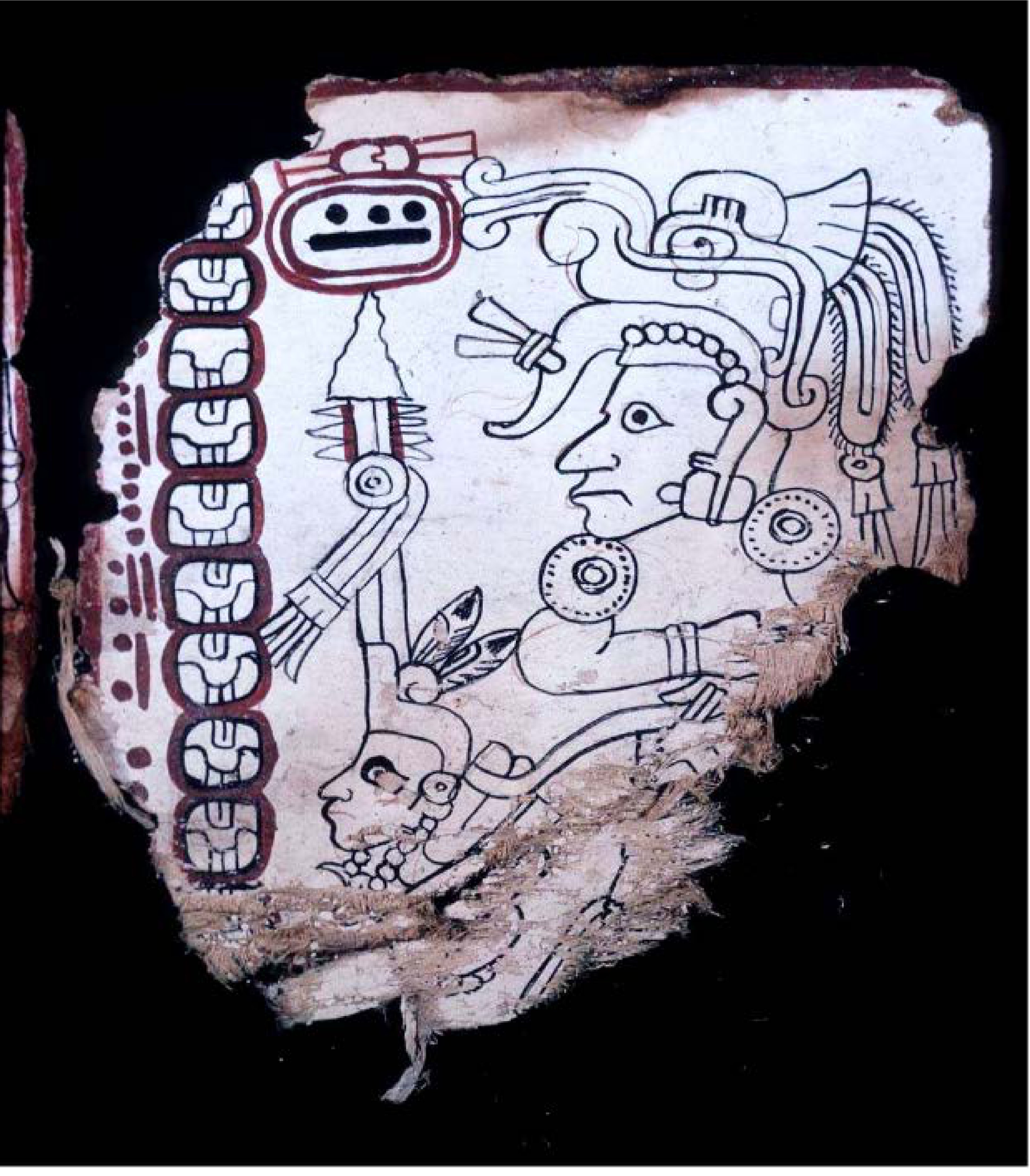

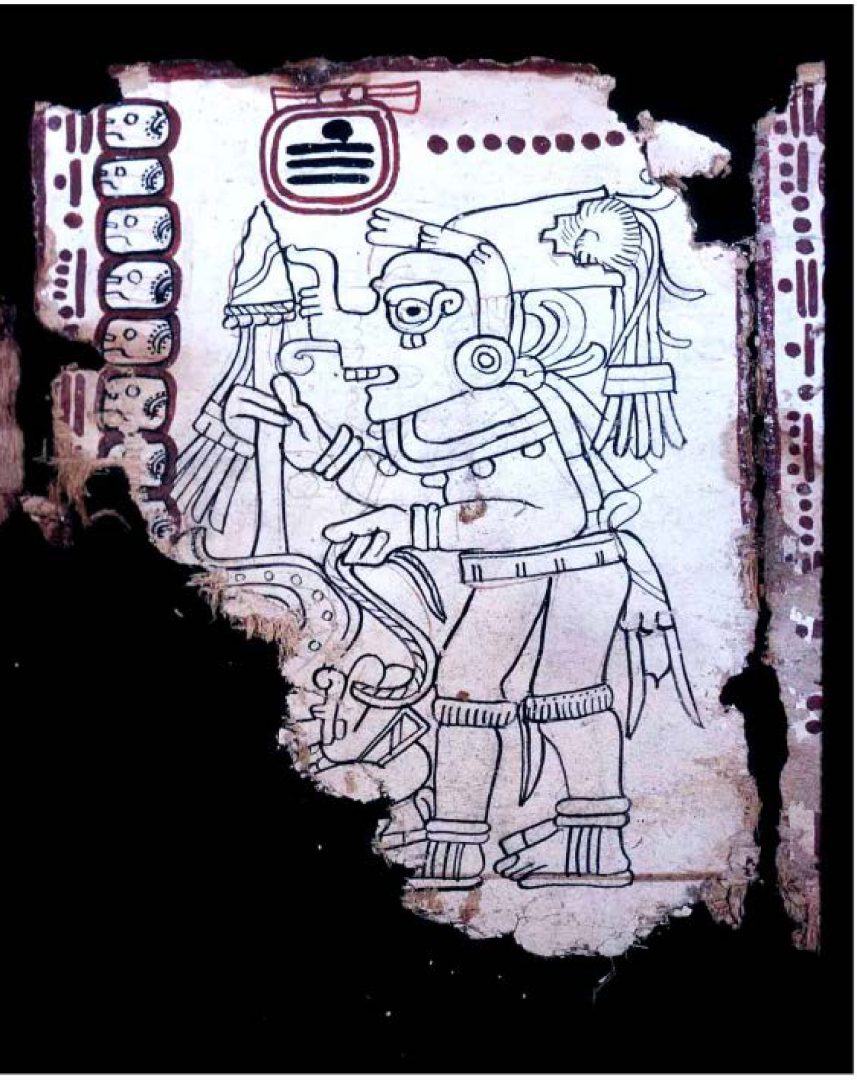

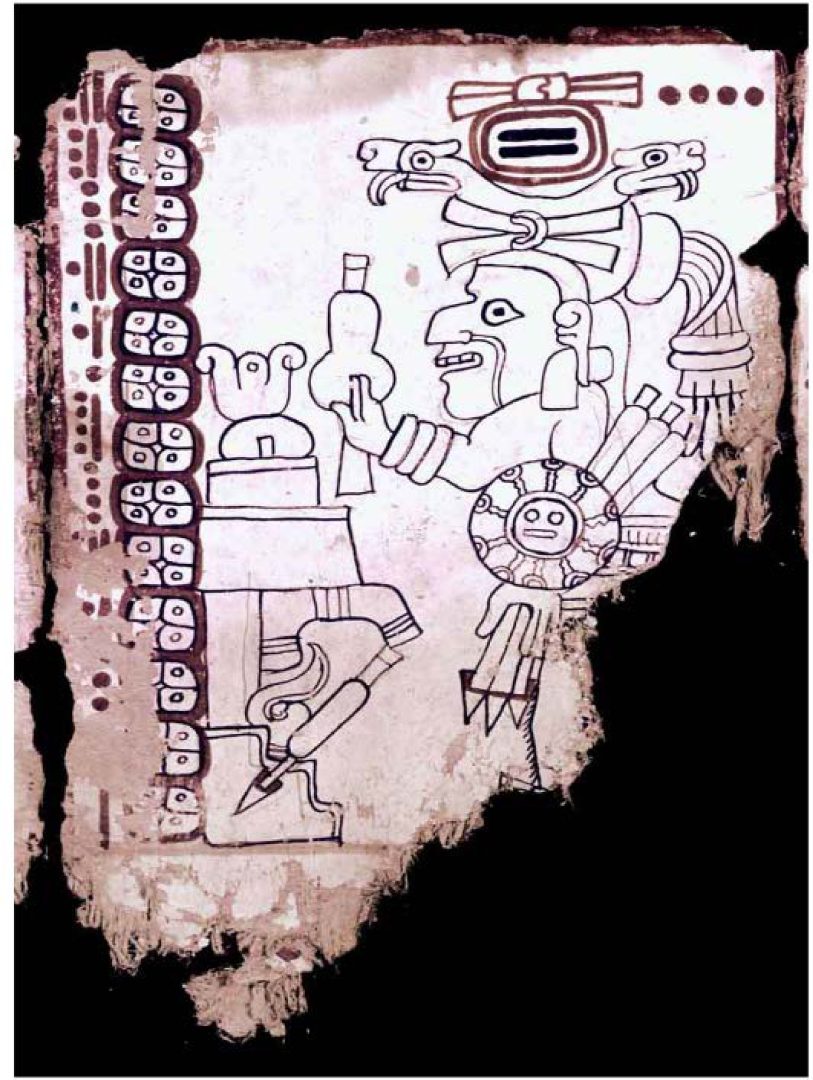

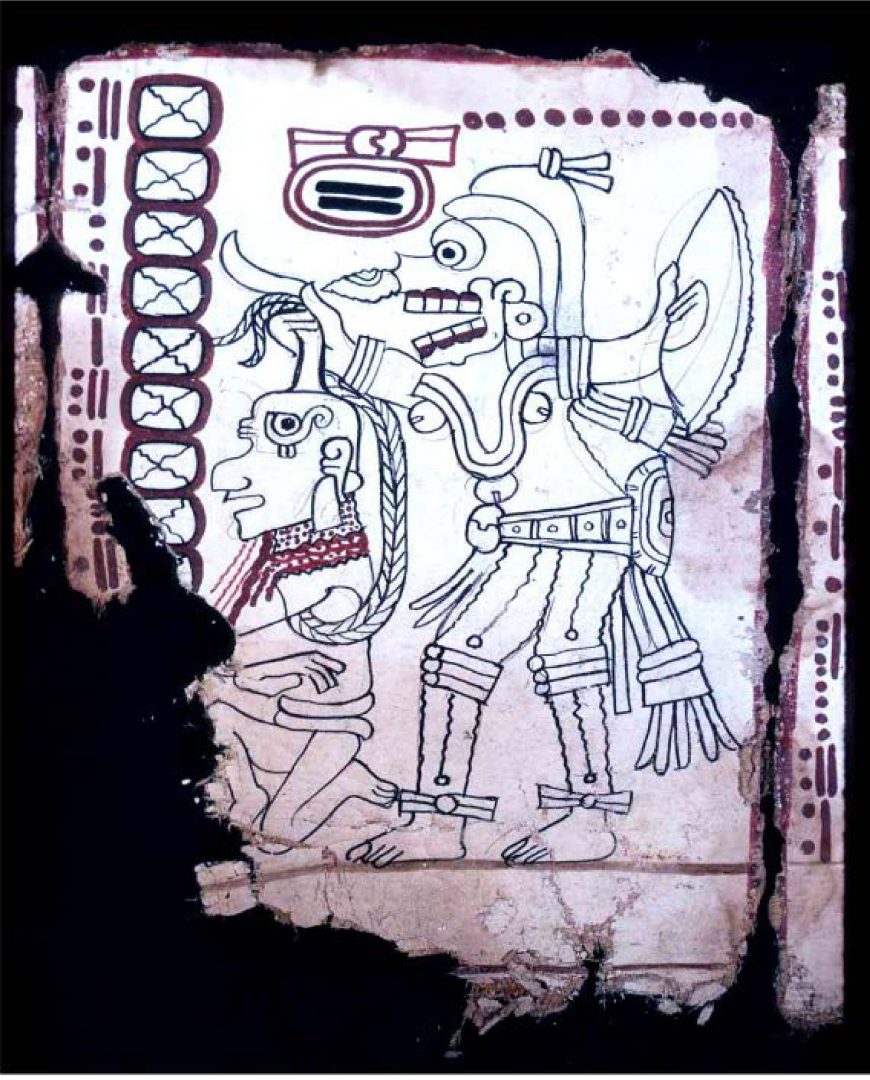

Sáenz took the items back to Mexico City for authentication. An expert he consulted declared them fakes, but Sáenz purchased the codex anyway in 1965. The manuscript, consisting of 11 damaged pages from a presumed 20-page book and 5 single pages, was made of amate (fig-bark paper). It was stuccoed and painted on one side. Its pages, typically 12.5 centimeters wide with the tallest fragment (Folio 8) measuring 19 centimeters. They bore numerical and calendrical glyphs alongside illustrations of Maya deities. Red frame lines at the bottom of pages four through eight suggest the codex was once taller. We find space prepared for text beneath each figure. The codex’s content, an almanac charting the movements of Venus, hinted at its significance. However, its murky origins cast a long shadow of doubt.

The Grolier Club Exhibition and Initial Doubts

In 1971, the Grolier Club in New York City displayed the codex, gaining it international attention. A private society of bibliophiles, as part of an exhibition titled “Ancient Maya Calligraphy,” curated by Yale anthropologist Michael D. Coe. The Grolier Club, founded in 1884, first photographed, published, and presented the codex, giving it the name “Grolier Codex.” Coe, who examined the manuscript in 1968 at Sáenz’s home in Mexico City, believed it was genuine. He notes its relation to the Dresden Codex, another Maya manuscript, in its focus on the Venus calendar. He published the first half-size recto-side facsimile in The Maya Scribe and His World (1973). This a Grolier Club publication, describing its style as a hybrid of Toltec and Mixtec influences.

However, the codex’s origins raised red flags. Its discovery by looters rather than archaeologists. More so, Sáenz’s decision to display it in New York instead of Mexico. The fantastical story of its acquisition did not help and it fueled scepticism. Critics like J. Eric S. Thompson, a prominent Maya scholar, denounced it as a forgery in 1975. He points to iconographic anachronisms, the lack of predictive omens and cardinal directions typical of Maya codices. Also, the possibility that blank fig-bark paper could have been used by modern forgers. Thompson and others, such as Claude Baudez, argued the codex’s simplicity and lack of hieroglyphic text made it “futile”. This when compared to the Dresden, Madrid, and Paris codices. All of which were authenticated earlier and considered canonical.

The Authenticity Debate: A Battle of Perspectives

For decades, the Codex Grolier was a lightning rod for debate. Its unconventional provenance as a looted artifact made scholars wary. Yet, its validation offered a glimpse into the Maya’s forgotten past that skeptics could no longer dismiss. The three other surviving Maya codices (Dresden, Madrid, and Paris), transported to Europe in the 16th century, were discovered under clearer circumstances, while the Grolier’s story seemed too outlandish. Sáenz’s account of a clandestine flight to an undisclosed airstrip, did not facilitated things. Furthermore, when combined with the codex’s differences, this being, less hieroglyphic text, simpler illustrations, and visible red sketch lines, fed doubts. Critics argued a forger could have used pre-Hispanic paper. In the same way, the codex’s lack of insect damage, unusual in a tropical climate, added to suspicions.

Yet, proponents like Coe saw its authenticity in its details. The codex’s Venus tables, tracking the planet’s 104-year cycle, aligned with Maya astronomical practices. Linking Venus movements to deities associated with warfare and misfortune. The illustrations, though simpler, depicted gods with weapons, among these we can find spears, darts, and knives. All consistent with Maya iconography. Coe’s 1973 analysis noted its hybrid style, blending Toltec and Mixtec influences, suggesting a transitional period in Maya art. Radiocarbon dating of one of the associated blank sheets in the 1970s dated it to 1230 ± 130 AD. Thus supporting its pre-Columbian origin, though skeptics like Thompson argued blank paper could have been repurposed.

Scientific Validation: Proving the Codex’s Age

In 2016, a team of scholars, including Stephen Houston of Brown University, Michael Coe, Mary Miller of Yale, and Karl Taube of UC-Riverside, conducted a comprehensive study published in Maya Archaeology. They reviewed all known research, using cutting-edge techniques like X-rays, UV imaging, and microscopic analysis. The study confirmed the codex’s authenticity. Dating it to between 1021 and 1154 AD, making it the oldest surviving manuscript from the Americas. Therefore predating the Dresden Codex by at least two centuries. The team found no modern materials in the paint. Specifically, the use of Maya Blue, a pigment of indigo and palygorskite not synthesized until the 1980s. This proved a forger in the 1960s couldn’t have replicated it. The codex’s paper, made from fig bark, and its iconography matched early Postclassic Maya practices. in short, reflecting a time of cultural transition after the Classic period’s decline (AD 250–900).

The National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) in Mexico formally recognized its authenticity on September 30, 2018, renaming it the Códice Maya de México. The INAH’s chemical tests, including non-destructive methods like Particle Induced X-ray Emission (PIXE) and Rutherford Backscattering Spectrometry (RBS), confirmed the presence of gypsum in the preparation layer, red hematite in the pigments, and carbon-based ink, consistent with pre-Hispanic materials. “However, researchers couldn’t conclusively pinpoint the blue pigment as Maya Blue due to limitations in elemental analysis, though comparisons with Maya Blue from Calakmul and Tulum sites bolstered its authenticity.

Significance: A Glimpse into the Maya’s Forgotten Past

The Códice Maya de México offers a glimpse into the Maya’s forgotten past, particularly their reverence for Venus, with deities depicted as fearsome figures wielding weapons. In this case, towards Maya cosmology, particularly their reverence for Venus. The planet, an omen of misfortune, connects to deities the codex portrays as fearsome figures wielding weapons, symbolizing cyclic conflicts. The calendar stretches across 104 years, hinting that multiple generations of ‘day-keepers’ or calendar priests employed it for divination and ritual timing, such as choosing when to launch wars. Its hybrid style, blending Toltec and Mixtec influences, reflects the early Postclassic period (AD 900–1250), a time of cultural flux as Classic Maya traditions waned and new artistic influences emerged from central and southern Mexico.

The codex’s simplicity, once a target of criticism, now reveals itself as a product of its era. As INAH researcher Sofia Martinez del Campo noted, ‘The austerity of the work stems from its epoch, when scarcity forces one to use whatever lies at hand. This pragmatic approach underscores the Maya’s resilience during a time of scarcity, using available resources to record their astronomical knowledge. The codex’s survival, likely thanks to the dry cave environment in Chiapas, stands as a miracle, since Spanish conquistadors and missionaries, deeming most Maya codices ‘falsehoods of the devil,’ torched them en masse during the 16th-century conquest.

Current Status and Legacy

Today, the Códice Maya de México rests in the vault of the National Library of Mexico, after curators relocated it from the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City, where staff stored it for years without public display. In 2018, the Museo Nacional de Antropología showcased it briefly during the XXIX International Book Fair of Anthropology and History, alongside a facsimile, before conservators returned it to secure storage. The INAH’s recognition included its incorporation into UNESCO’s Memory of the World program, affirming its global cultural significance.

The codex’s journey from doubted artifact to validated treasure provides a glimpse into the Maya’s forgotten past, a fragile whisper from a lost world that continues to captivate. Its lack of archaeological context, mainly due to its discovery by looters, limits our understanding of its original use, but its authenticity opens new avenues for research. Scholars can now explore its Venus tables, iconography, and cultural context, shedding light on Maya religious beliefs, astronomical knowledge, and artistic evolution during a pivotal period. The Códice Maya de México stands as a testament to the Maya’s enduring legacy, a fragile whisper from a lost world that continues to captivate and inspire.