The Azores, a remote volcanic archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, have long intrigued historians with their story of discovery. Traditional accounts credit Portuguese sailors with finding these nine islands around 1427 or 1432, describing them as untouched by human hands. Yet, compelling evidence from recent studies suggests a much earlier human presence, dating back to 700 CE and beyond. Research involving lake sediments, climate modeling, genetic analysis, and archaeological finds points to settlers, possibly Vikings, arriving centuries before the Portuguese. This article explores these discoveries, weaving together a revised narrative of the Azores’ past, enriched by the work of physicist Dr. Felix Rodrigues.

Sediments Tell a Different Tale

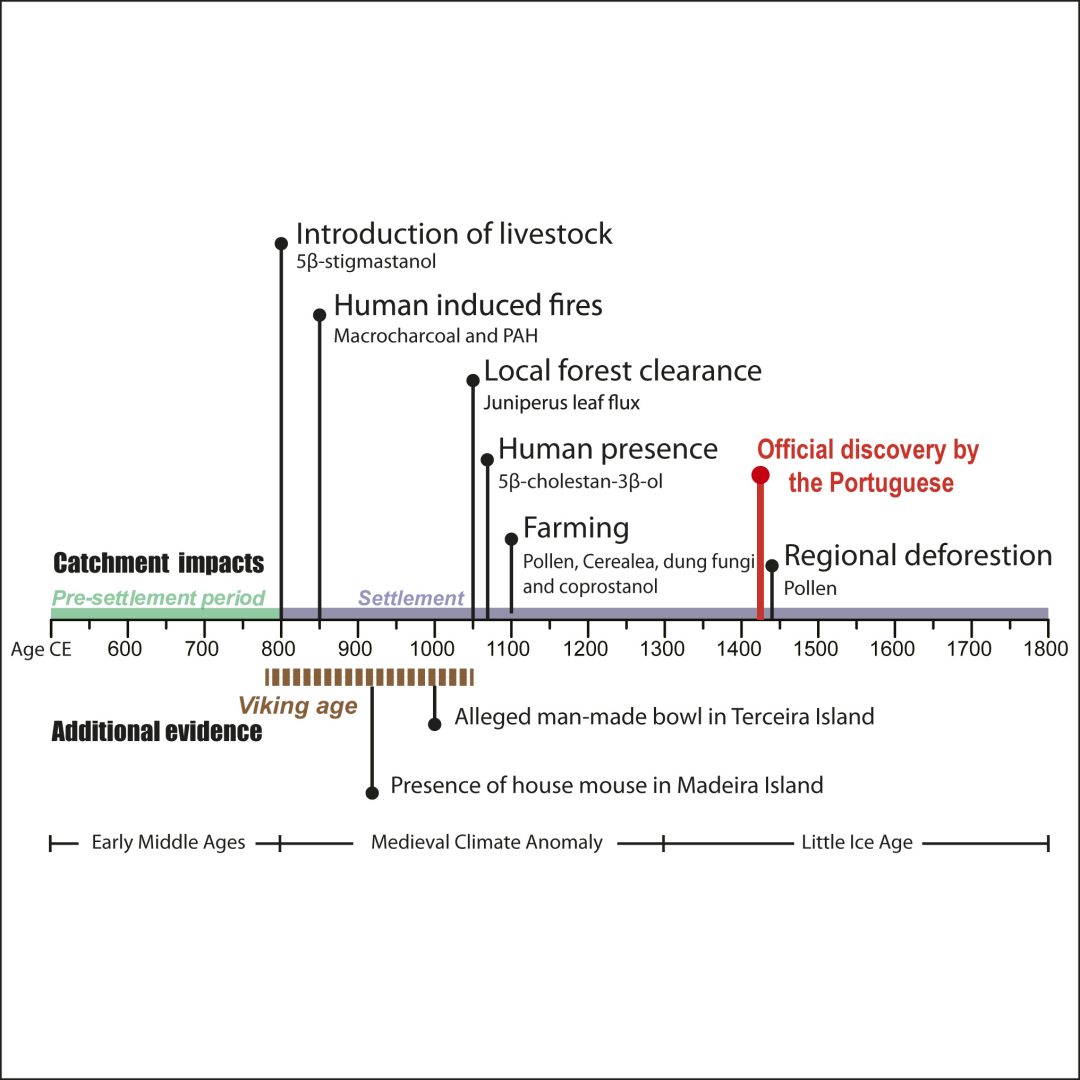

A multidisciplinary team of scientists extracted sediment cores from five Azorean lakes, São Miguel, Pico, Flores, Corvo, and Terceira; to study climate patterns. What they found shifted their focus to history. Around 700 CE, the sediments showed elevated levels of sterols and coprostanols, organic markers of human and livestock waste. Between 700 and 1070 CE, charcoal particles, plant fossils, and chemical traces of burning indicated deforestation and soil erosion. By 1100 CE, pollen from rye and broadleaf plantain (plants foreign to the Azores) suggested agriculture. These signs, uncovered in a study published in a prominent scientific journal, reveal human activity 700 years before the Portuguese arrived, contradicting the idea of pristine ecosystems.

Climate and Winds Point North

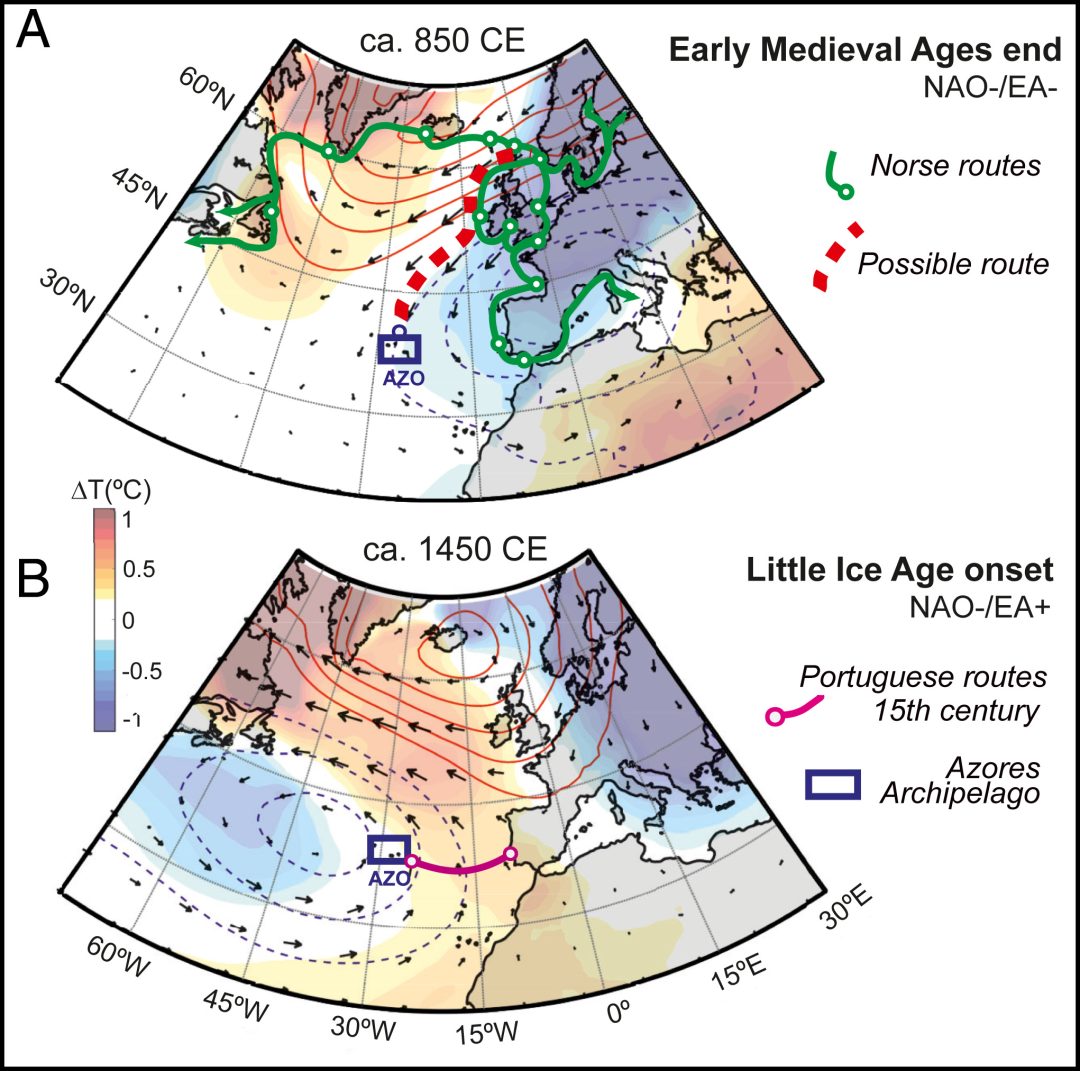

Climate simulations from 850 to 1850 CE offer clues about who these early settlers might have been. During the suspected settlement period around 700 CE, warm North Atlantic conditions and strong northeast winds prevailed. These winds posed a challenge for sailors from southern Europe, pushing them south of the Azores. However, they favored mariners from Scandinavia, where Vikings thrived as expert seafarers. Known for reaching Iceland, Greenland, and North America during this era, Vikings could have ridden these winds southwest to the Azores. By the 15th century, shifting wind patterns aided Portuguese voyages, explaining their later arrival. This climate data supports the notion of northern European pioneers predating southern explorers.

North Atlantic average anomalies for MSLP (blue/red lines), 2 m temperature (shading), and 925 hPa horizontal wind (vectors) during the 850 to 1500 CE period. (A) Average anomalies for MSLP (blue/red lines), 2 m temperature (shading), and 925 hPa horizontal wind (vectors) during NAO−/EA− prevailing conditions. Green line, Norse maritime routes during the ninth to eleventh century. Blue rectangle, location of the Azores Archipelago (AZO). Dotted orange, a possible route of Norse reaching the Azores Archipelago. (B) Average anomalies for MSLP (blue/red lines), 2 m temperature (shading), and 925 hPa horizontal wind (vectors) during NAO−/EA+ prevailing conditions. Magenta line, Portuguese maritime routes during fifteenth century. Blue rectangle, Azores Archipelago location.

Mice as Silent Witnesses

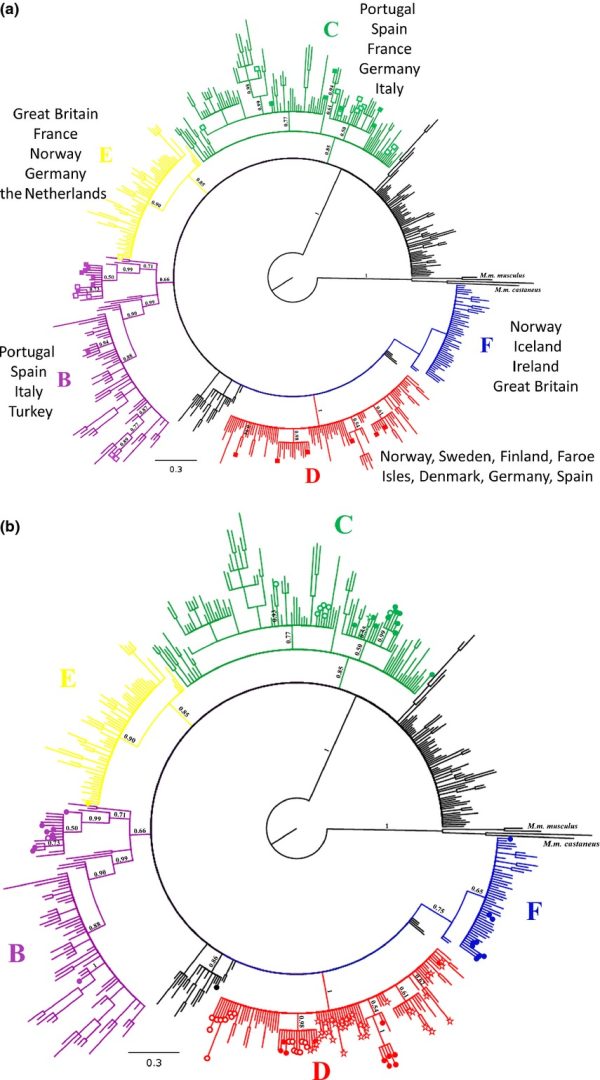

Genetic analysis of house mice across the Azores adds another layer to this story. Researchers examined mitochondrial DNA from 239 mice, finding most lineages tied to the Iberian Peninsula, consistent with Portuguese settlement. Yet, on Flores, Terceira, and São Miguel, distinct haplotypes linked to northern Europe emerged. House mice often hitch rides on ships, making them proxies for human travel. The presence of Scandinavian genetic markers suggests Norse voyages to the Azores before the Portuguese, with mice as unwitting passengers. This evidence aligns with sediment and climate findings, hinting at multiple waves of human contact.

Bayesian phylogenetic tree of previously published house mouse D-loop haplotypes in addition to our new Azorean and Spanish sequences. (a) Haplotypes detected in southern Spain (Gray et al., 2014 and this study) and mainland Portugal (Förster et al., 2009) are highlighted with solid and open squares, respectively. The European distribution of each clade is represented by a list of countries where the corresponding haplotypes are prevalent. See Appendix S2 for the detailed tree. (b) Haplotypes detected on the three Macaronesian archipelagos are highlighted with the following symbols: closed circles (Azores; this study), open stars (Madeira; Gündüz et al., 2001; Förster et al., 2009) and open circles.

Bonhomme et al., 2011; Jones et al., 2011a). The branches leading to haplotypes that do not fall into named clades are shown in black.

Image Credit: https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12550

Dr. Felix Rodrigues’ Archaeological Insights

Physicist Dr. Felix Rodrigues has spent over a decade uncovering physical traces of this early presence on Terceira Island, his home in the Azores. His work, conducted through meticulous field research, revealed man-made rock basins, megalithic stone arrangements, and petroglyph-like inscriptions near the Grota do Medo site. Using Accelerator Mass Spectrometry, Rodrigues dated these features to the 11th century or earlier, suggesting human activity long before the Portuguese era. He also identified dolmens, stone structures potentially used for burials, dated to at least 2,500 years ago, with nearby ceramics pushing the timeline back over 4,000 years. Rodrigues’ findings of stone anchors not known to the Portugues also allude to an older culture.

Piecing Together the Puzzle

The combined evidence paints a vivid picture. Sediments show altered landscapes and agriculture by 700 CE. Climate models favor northern voyagers like the Vikings. Mouse genetics suggest Scandinavian contact. Rodrigues’ discoveries provide tangible proof of early inhabitants, from rock basins to dolmens. Together, these findings challenge the Portuguese discovery myth, proposing the Azores as a waypoint in medieval exploration. The multidisciplinary approach, spanning geology, biology, and physics, reveals a complex history, with each method reinforcing the others. What began as a climate study evolved into a quest to identify the islands’ first settlers.

Vikings or Others?

Vikings emerge as strong candidates for these pioneers. Their seafaring skills and the favorable winds of the time align with the data. Rodrigues’ megalithic findings echo Norse construction styles, and mouse genetics bolster this hypothesis. However, alternatives exist. Irish monks, known to reach Iceland, could have ventured further south. The absence of Viking graves or settlements, unlike in other regions, raises doubts. Rodrigues notes striking similarities between Azorean structures and ancient cultures, yet no definitive cultural signature emerges. The lack of written Norse records about the Azores adds to the uncertainty, leaving room for debate.

Lingering Questions

This revised history sparks new mysteries. Fourteenth-century European maps depicted the Azores before Portuguese colonization; how did this knowledge spread? Did Portuguese explorers encounter remnants of earlier settlers, and if so, why omit them from records? Rodrigues’ cart ruts and dolmens suggest a significant presence, yet no villages or cemeteries have surfaced. The ecosystems, altered by 700 CE, never fully recovered, but human traces faded before 1432. Future digs, especially on islands with northern mouse haplotypes, could clarify these gaps. Rodrigues advocates for collaboration with historians and archaeologists to refine the timeline and identify the settlers.

A New Azorean Legacy

The Azores’ story now stretches back over a millennium earlier than once thought. Sediment cores, climate data, mouse DNA, and Rodrigues’ archaeological work converge on a pre-Portuguese settlement by 700 CE, likely from northern Europe. This interdisciplinary effort not only rewrites history but also positions the Azores as a key node in medieval maritime networks. As research progresses, the islands’ hidden past promises to yield more secrets, blending science and discovery to illuminate a forgotten chapter of human exploration.