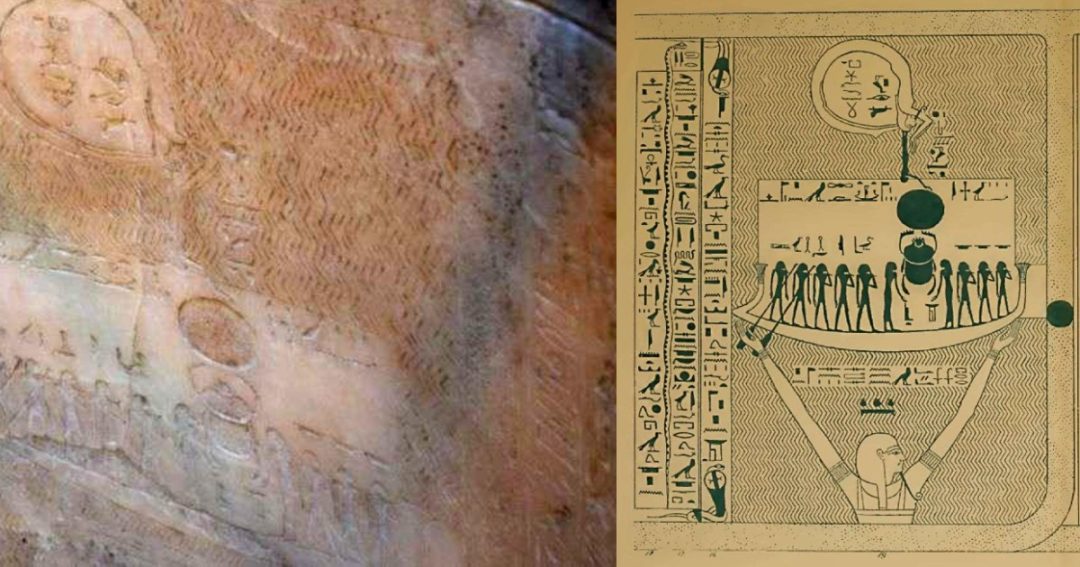

The birth of the cosmos takes center stage in a groundbreaking reevaluation published in the Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society. The authors challenge long-standing interpretations of the imagery on the ˁAin Samiya goblet. A 4,300-year-old silver artifact from the Intermediate Bronze Age. Discovered in a tomb in the Judean Hills, this 8 cm tall goblet bears intricate repoussé and incised decorations. Depicting mythological scenes with chimeras, snakes, plants, anthropomorphic figures, and celestial symbols. The study argues that these motifs do not represent violent battles from Babylonian epics like Enuma Elish. Instead they depict creation and cosmic order, centered on the birth and journey of the sun. This interpretation positions the goblet as one of the earliest known depictions of ancient Near Eastern cosmology. Reinforced by comparisons to artifacts from Göbekli Tepe to the sarcophagus of Seti I.

ˁAin Samiya Goblet Discovery

The ˁAin Samiya goblet was unearthed in 1970 during during the excavation of a tomb near the village of ˁAin Samiya. ˁAin Samiya is located in the Ramallah and al-Bireh governorate of the West Bank. This double-chambered shaft tomb was part of a vast Intermediate Bronze Age cemetery in Wadi Samiya. The tomb contained undisturbed artifacts including ceramic vessels, lamps, weapons, and beads, dating to around 2200 BCE. The valley, rich in water from the ˁAin Samiya spring, served as a major burial ground for nomadic or semi-nomadic communities.

The Intermediate Bronze Age in the southern Levant marked a shift from urban Early Bronze Age societies to smaller, kinship-based groups, emphasizing communal burials. The silver goblet, stands out as the only elite grave good from this period in the area. Likely intended to aid the deceased’s rebirth by connecting their soul to cosmic cycles.

ˁAin Samiya Goblet Motifs

The goblet’s frieze divides into two symmetrical scenes. The right scene shows two anthropomorphic figures, dressed in tunics and headdresses, holding a crescent-shaped object adorned with circles, above which floats an eleven-petaled rosette with a human face. Below lies a coiled snake with hatched skin.

The left scene features a chimera with a human upper body (nipples and navel emphasized) and conjoined bull-like lower bodies with four legs. It holds stylized plants, flanked by an eight-petaled rosette without a face and an upright snake with circular skin patterns. Geometric bands of chevrons and herringbones border the base.

These elements (chimeras, snakes, plants, and astral symbols) evoke themes of chaos transitioning to order, the birth of the cosmos. With the crescent identified as a “Celestial Boat” for solar journeys.

Previous Interpretations and Criticisms

Shortly after discovery, Yigael Yadin linked the goblet to Enuma Elish, interpreting the left scene as Marduk confronting chaos monster Tiamat and the right as her defeat. This view influenced many, but critics like Wilfred Lambert and Noga Ayali-Darshan noted the goblet predates the epic by over 1,000 years and lacks violence. The authors concur, arguing the scenes depict non-combative cosmology.

A New Cosmological Interpretation

Zangger et al. propose the goblet illustrates the emergence of cosmic order from chaos. Focusing on the sun’s birth and journey. The left scene represents primordial fusion (deities, animals, and plants undifferentiated under chaos, the snake) while the right shows separation into ordered realms, with deities upholding the Celestial Boat to maintain balance. The goblet’s sun rosettes evolve from faceless (birth) to anthropomorphic (maturity), the birth of the cosmos.

The Celestial Boat: An Enduring Symbol of Cosmic Order

Göbekli Tepe

At the heart of this reinterpretation is the Celestial Boat, a crescent-shaped icon often paired with circular elements representing the divine realm. This symbol evolves over time, embodying the transport of celestial bodies and the maintenance of universal balance. Its earliest manifestation appears in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period at Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Anatolia, dating to around 9500 BCE. Here, on a pillar in Enclosure D, the motif signifies an otherworldly vessel. Hinting at early human conceptualizations of the heavens as a navigable domain protected by deities.

Ancient Egpyt

This iconography persists and adapts in later cultures. In Egyptian cosmology, it manifests vividly in the closing scene of the sarcophagus of Pharaoh Seti I (1279 BCE). Where the primordial god Nun lifts the solar barge, symbolizing the sun’s rebirth from the waters of chaos. This act of elevation represents the daily renewal of the cosmos. Safeguarding the world from disorder and ensuring the continuity of life. The motif’s presence in royal tombs underscores its role in facilitating the soul’s journey to the afterlife. A theme echoed across Near Eastern traditions.

Hittites

Further north, in the Hittite sanctuary of Yazılıkaya (c. 1230 BCE) in central Anatolia, bull-men figures hold a similar crescent, evoking eternal lunar cycles and the divine upholding of cosmic structure. These hybrid beings, part human, part animal, embody the fusion of earthly and celestial forces, protecting against chaotic intrusions. The relief’s integration into a rock-cut chamber suggests ritual significance, linking the motif to seasonal renewal and fertility rites.

Şanlıurfa

The paper introduces another key artifact: the Lidar Höyük prism (c. 2000–1600 BCE), published for the first time in this study. This prism depicts a quartered celestial body within a crescent, reinforcing the boat’s role in cosmological narratives. Originating from northern Mesopotamia, it bridges early symbolic traditions with later Bronze Age expressions, illustrating how such motifs facilitated cultural exchange along trade routes.

From Chaos to The Birth of the Cosmos

These artifacts reveal a unified motif that transcends individual sites, pointing to a pan-Near Eastern understanding of the cosmos as a dynamic entity requiring divine intervention. Symbols like snakes (representing chaos or renewal), chimeras (fusing human, animal, and plant forms to depict primordial unity), and rosettes (evolving from faceless orbs to anthropomorphic suns) illustrate the transition from undifferentiated chaos to ordered creation.

In Mesopotamian lore, this aligns with themes of deities separating heaven and earth. In Egyptian contexts, it mirrors the sun god Ra’s nightly voyage through the underworld. Among the Hittites, it supports lunar and solar cycles tied to agricultural prosperity.

Significance and Future Directions

This analysis reshapes our view of ancient Near Eastern cosmology, favoring themes of harmony and renewal over conflict. It predates formalized epics like Enuma Elish yet shares conceptual roots. suggesting a deep-seated human impulse to order the universe symbolically. For modern scholars, it invites interdisciplinary approaches. Combining archaeology, iconography, and comparative mythology, to explore how these motifs influenced later civilizations. From Greco-Roman astronomy to contemporary understandings of cosmic origins.

Funded by Luwian Studies, the paper calls for reevaluating other artifacts through this lens. Potentially revealing a “unified motif” that binds the ancient world. As excavations continue, symbols like the Celestial Boat may illuminate not just the birth of the cosmos. But also the enduring human quest for meaning in the stars.

For more on ancient symbolism check out Senenmut’s Star Map: Unlocking Cosmic Secrets of Ancient Egypt