Recent excavations at the Gran Dolina cave site (Atapuerca, Spain) have yielded critical insights into the behavioral practices of Homo antecessor, an archaic hominin species inhabiting Europe approximately 850,000 years ago. Analysis of a juvenile cervical vertebra (C3) reveals unambiguous evidence of perimortem processing—the oldest confirmed case of hominin cannibalism to date. This finding, documented in a Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences study, underscores systematic cannibalism as a recurrent survival strategy among these early human relatives.

Evidentiary Basis and Analytical Methodology

- Fossil Provenance and Identification

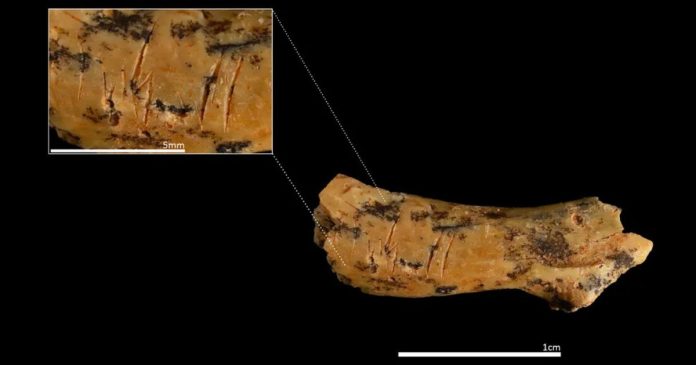

The vertebra (designated within the Gran Dolina TD6 assemblage) belonged to a child aged 2–5 years. Its exceptional preservation enabled high-resolution microscopic analysis, which identified multiple cut marks concentrated near muscle attachment sites (anterior tubercle and posterior elements). The marks’ morphology and trajectory align precisely with stone tool incisions, excluding carnivore damage or taphonomic abrasion as alternative explanations. - Taxonomic and Taphonomic Context

- The bone was found alongside nine additional H. antecessor skeletons, all exhibiting similar butchery patterns (defleshing cuts, intentional bone fracturing).

- Bite marks on several bones confirm consumption by conspecifics. Roughly 30% of the 10,000+ fossils excavated from Gran Dolina display anthropogenic modifications, indicating cannibalism was neither isolated nor ritualistic but a sustained behavioral practice.

- Chronological Significance

Dated stratigraphically to 850,000–780,000 years ago, this specimen predates all known Neanderthal cannibalism cases by >500,000 years. It surpasses disputed evidence from Kenya (1.45 million years ago) in diagnostic clarity, establishing H. antecessor as the earliest confirmed practitioner of hominin cannibalism.

Behavioral and Evolutionary Implications

- Resource Utilization under Pleistocene Constraints

The homogeneity of cut marks across human and animal bones at Gran Dolina suggests H. antecessor processed hominin carcasses identically to prey species. Researchers hypothesize nutritional stress or territorial competition drove this behavior, potentially as a response to scarce resources in Ice Age Europe. - Demographic Patterns in Cannibalism

Juvenile remains are disproportionately represented among cannibalized fossils. This may reflect vulnerability during resource shortages or non-nutritional factors like intergroup conflict. The precision of cuts on the toddler’s vertebra indicates sophisticated butchery knowledge, irrespective of the victim’s age. - Phylogenetic Debates Revisited

As H. antecessor fossils exist solely at Atapuerca, their role in human evolution remains contested. While some researchers propose them as direct ancestors of Neanderthals and modern humans, others suggest a divergent lineage. Cannibalism evidence may inform social complexity and adaptive flexibility in this pivotal species.

Research Trajectories and Unresolved Questions

Excavations at Gran Dolina continue to yield new H. antecessor remains annually. Future priorities include:

- Motivational Analysis: Differentiating survival-driven cannibalism from cultural or violent practices via cut-mark distribution and site spatial data.

- Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction: Correlating cannibalism episodes with climatic shifts inferred from sedimentology and fauna records.

- Comparative Taphonomy: Contrasting Gran Dolina modifications with those at contemporaneous sites to establish behavioral uniqueness.

Conclusion: Redefining Early Hominin Behavioral Ecology

This research transforms understanding of H. antecessor’s behavioral repertoire. Cannibalism—documented here with unprecedented antiquity—reflects either extreme ecological adaptability or social complexity preceding later hominins. As Palmira Saladié (excavation co-director) emphasizes, “The treatment of the dead was not exceptional, but repeated” across millennia at Atapuerca. Such findings necessitate reevaluating cognitive and survival capacities during the initial peopling of Europe.