Long before the rise of Sumerian temple cities or the first dynasties of Egypt, the Cucuteni‑Trypillian culture flourished across the forest‑steppe zone of modern Ukraine, Moldova, and Romania. This remarkable civilization (5200 to 3500 BC) built some of the largest and most organized settlements anywhere in the prehistoric world. For decades, these communities were overshadowed by the monumental stone architecture of the Near East. Dismissed as peripheral or misunderstood as scattered villages.

Yet the last twenty years of geomagnetic research have revealed a very different picture. Beneath the fertile black soils of Eastern Europe lie the remains of vast proto‑cities. We find ritual complexes, and sacred structures that challenge long‑held assumptions about the origins of urban life. The Cucuteni‑Trypillian world was not a footnote to early civilization. They were a major center of innovation, spirituality, and communal engineering during a deep timeframe. When most of Europe was still sparsely populated by small farming hamlets.

Rediscovery and the Birth of a New Archaeological Narrative

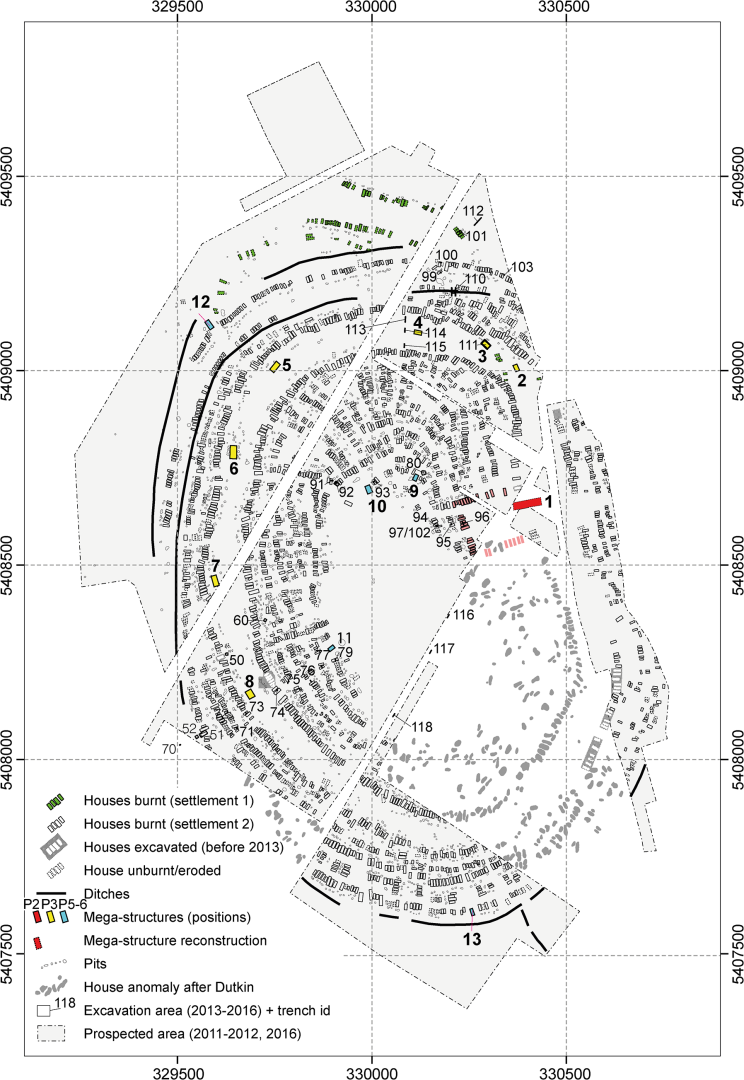

The story of the Cucuteni‑Trypillian rediscovery began in the late nineteenth century, when Romanian archaeologist Teodor Burada uncovered painted pottery near the village of Cucuteni. Around the same time, Ukrainian researchers excavating near Trypillia found similar ceramics, establishing the cultural unity of the region. Early excavations revealed unusually large settlements, but without modern surveying tools, their full scale remained invisible. It was not until the early twenty‑first century that geomagnetic surveys transformed the field. These non‑invasive scans mapped entire settlement plans beneath the soil, exposing concentric rings of houses, radial streets, central plazas, and monumental structures that had been hidden for millennia.

This remarkable Cucuteni‑Trypillian artifact (4,000 BCE) May be the oldest object ever found with wheels.

Source: “The Wheel” Columbia Studies in International and Global History, Richard W. Bulliet, Columbia University Press New York.

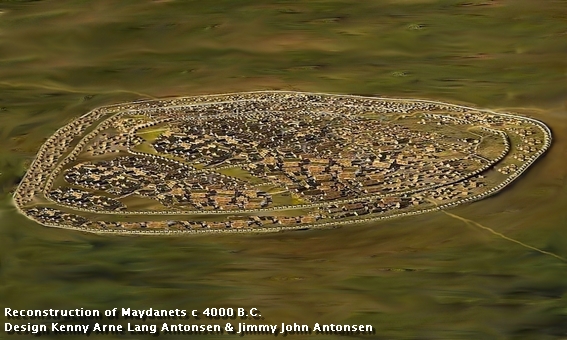

Sites such as Maidanetske, Talianky, Dobrovody, and Nebelivka emerged as sprawling proto‑urban landscapes. Some covered more than 250 hectares, with estimated populations rivaling or surpassing contemporary Mesopotamian centers like Uruk. According to the Trypillia Mega‑Sites Project, these were among the largest settlements on Earth between 4100 and 3600 BC. Their discovery forced scholars to reconsider the Eurocentric narrative that placed the origins of urbanism exclusively in the Near East. The Cucuteni‑Trypillian world demonstrated that large, organized communities could emerge independently, shaped by their own cosmology and social logic.

Life Inside the Mega Settlements

Archaeological evidence reveals a society deeply rooted in agriculture, craft specialization, and ritual expression. The Trypillians cultivated wheat, barley, peas, and flax, and raised cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs. Their pottery, decorated with swirling red, black, and white motifs, stands among the most sophisticated ceramic traditions of prehistoric Europe. Figurines depicting women, animals, and abstract symbols suggest a symbolic system that may have emphasized fertility, cosmology, and the cycles of nature.

Cucuteni‑Trypillian settlements themselves were meticulously planned. Houses were built from wattle and daub, often two stories tall, with ovens, storage vessels, and painted interiors. Many settlements followed a concentric layout, with rings of houses surrounding a central open space. This pattern suggests a communal ethos rather than a hierarchical one. Unlike Mesopotamia, where temples and palaces dominated the urban core, Trypillian settlements appear to have been organized around shared ritual and social spaces. The absence of elite residences or defensive fortifications hints at a society that valued cooperation and ritual cohesion over centralized authority.

One of the most enigmatic aspects of Trypillian life was the cyclical burning of settlements. Every few generations, entire communities were intentionally set ablaze. The reasons remain debated, but the practice appears to have been ritualized rather than accidental. The burning hardened the clay architecture into a ceramic‑like state, preserving the layout of houses and their contents. This “firing of the village” created a unique archaeological record and may have symbolized renewal, purification, or the closing of a cosmological cycle.

The Nebelivka Temple and the Emergence of Sacred Architecture

The most transformative discovery in recent years came from the settlement of Nebelivka, where geomagnetic anomalies revealed a massive structure unlike any typical dwelling. Excavations in 2012 confirmed it as a monumental temple complex dating to 4000–3900 BC, covering approximately 1200 square meters. This makes it one of the oldest known temple structures in Europe.

The Nebelivka Temple contained seven fire altars, a raised clay podium, ritual grinding stones, ceremonial vessels, and a symbolic pit marked with red ochre at the center of the main hall. The building was precisely aligned to the east‑west axis, with its entrance facing the rising equinox sun. This orientation reflects a cosmological worldview in which celestial cycles governed ritual life. The temple’s internal “sun corridor,” narrowing toward the central chamber, appears designed to concentrate sunlight on the main ritual symbol during sacred days of the year.

The discovery of the Nebelivka Temple provided a template for identifying similar structures across other settlements. More than 110 “megastructures” have now been recorded through geomagnetic surveys, many sharing the same spatial logic: placement on elevated ground, orientation toward the sunrise, and separation from residential zones. These were not random buildings but sacred centers that anchored the spiritual and social life of each community.

A Civilization Ahead of Its Time

The uniqueness of the Cucuteni‑Trypillian culture becomes even more striking when placed within its global timeframe. Between 5000 and 3500 BC, Mesopotamia was only beginning to form temple towns. Egypt had not yet unified under pharaonic rule. Stonehenge was still two thousand years in the future, and the Indus Valley Civilization had not yet emerged. Yet in the forest‑steppe of Eastern Europe, a network of mega‑settlements flourished, connected by shared architectural traditions, pottery styles, and ritual practices. Their settlements were larger than any contemporary European culture and rivaled the earliest cities of the Near East.

What sets them apart is the absence of features typically associated with early urbanism. There were no palaces, no monumental stone architecture, no centralized kingship, and no evidence of rigid social stratification. Their society appears to have been decentralized, communal, and ritually oriented. This makes the Cucuteni‑Trypillian world an anomaly in the global story of early cities; proof that large, complex settlements could exist without authoritarian structures or militarized elites.

The Mystery of Their Disappearance

Around 3500 BC, the mega‑settlements were gradually abandoned. Climate change, soil exhaustion, and the arrival of steppe pastoralists from the Pontic‑Caspian region may have contributed to their decline. Yet the cultural legacy of the Cucuteni‑Trypillian world persisted in the symbolic traditions, pottery motifs, and settlement patterns of later European cultures. Their disappearance remains one of prehistory’s great mysteries, but their rediscovery has reshaped our understanding of ancient Europe.

A Civilization Worthy of Renewed Attention

The Cucuteni‑Trypillian culture stands as one of the most remarkable prehistoric civilizations ever uncovered. Their mega‑settlements challenge traditional narratives about where and how urban life began. Its temples reveal a sophisticated cosmology. Their artifacts reflect a people deeply connected to ritual, community, and the cycles of nature. As geomagnetic surveys continue to uncover new sites, the story of the Cucuteni‑Trypillian world grows richer, and its place in the history of human civilization becomes impossible to ignore.

Author’s Note

When I study the Cucuteni‑Trypillian world, I’m struck by how profoundly unmilitarized it was. Across thousands of excavated structures, there are no arsenals, no warrior burials, no fortifications, and almost no weapons beyond simple hunting tools. Their settlements were open, their houses arranged in harmonious rings, their temples aligned to the rising sun. Everything about their material culture suggests a people invested in ritual, agriculture, and communal life rather than conflict. It is a rare thing in prehistory to encounter a society of this scale that left behind no trace of a warrior class.

And yet, when their timeline intersects with the arrival of steppe groups—people who rode horses, carried axes and spears, and used bows with practiced skill—it’s difficult not to feel a jolt of narrative tension. The contrast is stark. On one side, a settled culture with painted pottery, sunrise‑oriented sanctuaries, and no martial infrastructure. On the other, highly mobile pastoralists whose toolkit included the very technologies that would reshape Europe for millennia. Archaeology does not show scenes of slaughter, but the emotional imagination can’t help but picture the vulnerability of a peaceful society confronted by newcomers who lived by a different code.

There is no evidence for a single violent end, yet the juxtaposition of these two worlds lingers in the mind. The Trypillians built some of the largest settlements of their age without swords, shields, or walls. The people who followed them did not share that approach to life. That contrast alone is enough to stir a quiet, haunting sense of what might have happened at the edges of their world, even if the soil preserves only silence.