Introduction: A Neolithic Challenge to History

The Dispilio Tablet challenges history with ancient markings that defy our understanding of early human communication. Unearthed in 1993 near Kastoria, Greece, this wooden artifact, dated to 5200 BCE, may represent humanity’s earliest writing, taking it back to a staggering 7,200 years ago. Discovered by archaeologist George Hourmouziadis, its linear symbols provoke a fierce debate. Is this a script predating Mesopotamian cuneiform, or a symbolic relic of a Neolithic mind? Housed in the Museum of the Prehistoric Lakeside Settlement, the tablet stands as a defiant enigma. Its existence urging us to rethink the dawn of literacy and the sophistication of Neolithic Europe.

Discovery at the Dispilio Settlement: A Window into the Neolithic

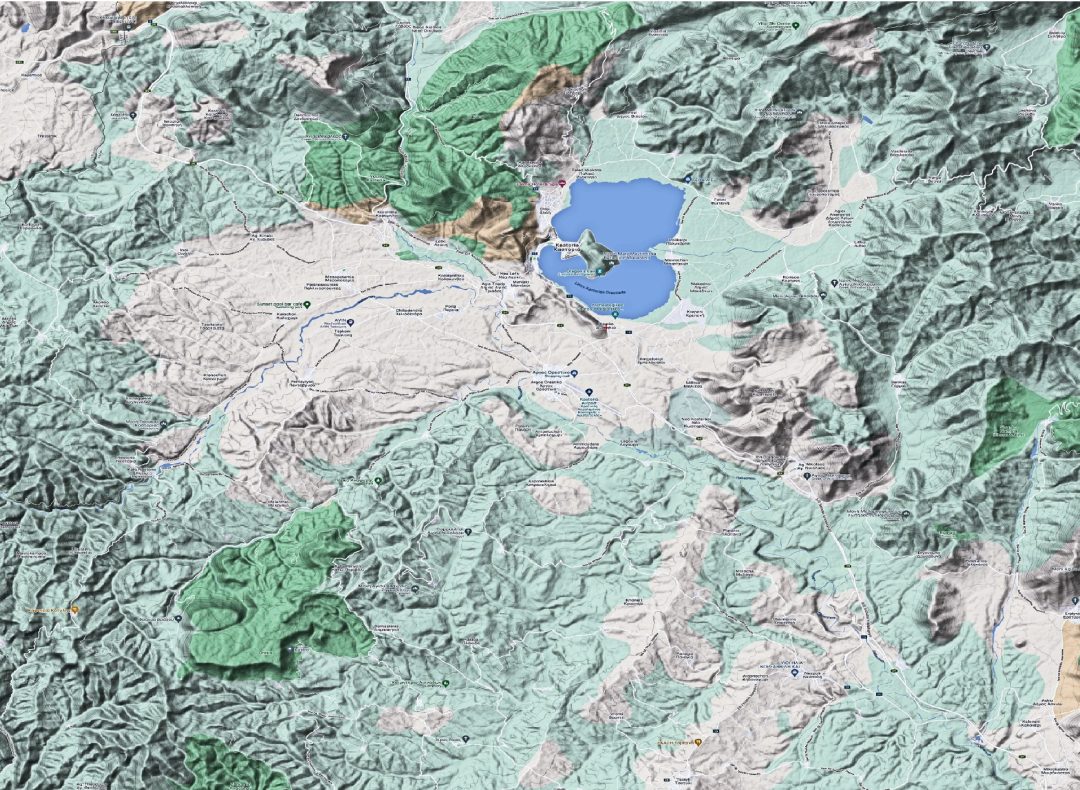

Found at a Neolithic lakeside settlement on the shores of Lake Orestiada, near Kastoria in northern Greece. This prehistoric village, thriving from 5600 to 3000 BCE, was a marvel of early engineering. All of it, built on stilts over the lake. In itself, a testament to the ingenuity of its inhabitants. The settlement, covering approximately 2 hectares (5 acres), consisted of wooden platforms supporting huts, surrounded by a palisade for protection. Excavations were led by George Hourmouziadis, a professor at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. His team revealed a community with advanced agricultural practices. This including the cultivation of wheat, barley, and lentils, alongside domesticated animals like pigs and sheep. The villagers crafted pottery, bone tools, and figurines, showcasing a rich material culture.

Hourmouziadis’ team unearthed the tablet in 1993. Found within a layer associated with the site’s final occupation phase, around 5200–5260 BCE. Radiocarbon dating of organic materials, such as wooden posts and seeds found nearby, confirmed this timeline. These were detailed by Fakorellis and Maniatis in their 2000 study published in Radiocarbon. The anaerobic conditions of the lakebed preserved organic artifacts like the tablet, which would have otherwise decayed. This preservation offers a rare glimpse into the organic world of the Neolithic. Otherwise, wood, textiles, and other perishable materials typically vanish from the archaeological record. The discovery of the site itself, now partially reconstructed, allows visitors to envision a bustling lakeside community. A strong contestant on assumptions of Neolithic simplicity with its organized complexity.

Structure and Markings: A Potential Script Emerges

The Dispilio Tablet is a small, rectangular wooden piece, measuring 19 cm by 6 cm (7.5 in by 2.4 in) and about 2 cm (0.8 in) thick. Its surface bears a series of linear symbols, etched with a sharp tool, that resemble ideograms or a rudimentary script. The markings are arranged in rows, with some symbols appearing as simple lines, crosses, or geometric shapes. But we can also find others, more complex, possibly representing objects or concepts. The tablet’s fragility, due to its organic composition, makes it a delicate artifact. A miracle of preservation in the waterlogged lakebed allowed it to survive for over 7,200 years .

The symbols’ arrangement has led some researchers to propose they constitute an early form of writing or proto-writing. This a system of symbols used to convey meaning, potentially predating known scripts like Sumerian cuneiform (3100 BCE) or Egyptian hieroglyphs (3100 BCE). Hourmouziadis, in his 2002 book Dispilio: 7500 Years After, argued that the markings exhibit intentional structure, suggesting a communicative purpose. However, the lack of systematic repetition or a clear phonetic system has fueled skepticism. Some symbols bear a superficial resemblance to later scripts, such as the Vinča symbols (4500–4000 BCE). But also of Linear A (1800–1450 BCE), these comparisons are tenuous due to the vast time gap. The tablet’s markings, whether script or symbol, challenge us to reconsider what Neolithic minds were capable of expressing.

Cultural Significance: A Testament to Neolithic Sophistication

The Dispilio Tablet offers a profound insight into the cultural complexity of its Neolithic creators. The Dispilio settlement was not a primitive encampment but a thriving community with advanced social organization. Archaeological evidence reveals a division of labor, with specialized roles for potters, farmers, and toolmakers. The villagers constructed wooden boats for fishing, wove baskets, and produced ceramic vessels with intricate designs, indicating a high level of craftsmanship. Their diet, rich in grains, legumes, meat and fish, supported a stable population, likely numbering in the hundreds, which in turn enabled communal projects like the stilted village.

The tablet’s purpose remains a matter of speculation, but several theories highlight its cultural weight. If the markings are a form of writing, they could have served practical purposes, such as recording harvests, trade, or communal events. Therefore, an early accounting system predating Sumerian clay tablets by 2,000 years. Alternatively, the symbols might have held ritual significance, perhaps used in ceremonies to honor deities or ancestors. Hourmouziadis suggested they could mark ownership or social roles, a proto-script for a community beginning to formalize its hierarchy. Even if symbolic rather than linguistic, the tablet reflects a Neolithic society capable of abstract thought, defying the notion that such cultures were solely focused on survival.

A Genesis For The Written Word?

Maybe not, who knows what more will we find and where. Comparatively, the tablet aligns with other early symbolic systems in southeastern Europe. The Vinča culture, flourishing around 4500–4000 BCE in the Balkans, left behind thousands of inscribed objects, as detailed by Winn in Pre-Writing in Southeastern Europe (1981). These symbols, often on pottery, are considered proto-writing, used for ritual or economic purposes. The Dispilio Tablet, predating Vinča by nearly a millennium, suggests that symbolic communication may have deeper roots, challenging the Mesopotamia-centric narrative of writing’s origins. Its discovery underscores Neolithic Europe’s intellectual vibrancy, a region often overshadowed by the Near East in early literacy studies.

Preservation Challenges: A Fragile Relic Under Threat

The Dispilio Tablet’s organic nature makes it a rare find, but also a fragile one. Unearthed from the anaerobic lakebed, it was well-preserved until exposure to air triggered rapid deterioration. The wood began to crack and degrade, complicating initial studies of the markings. Conservators at the Museum of the Prehistoric Lakeside Settlement in Dispilio, where the tablet is housed, placed it in a controlled environment with regulated humidity and temperature to halt further damage. Public access is restricted due to its fragility, though a replica is often displayed for visitors.

Advanced imaging techniques, such as 3D scanning and X-ray analysis, have been employed to study the markings without physical handling. These methods allow researchers to examine the depth and structure of the incisions, potentially revealing more about their creation process. However, the tablet’s condition remains a barrier to comprehensive analysis. Papakostas, in his 2013 guide The Prehistoric Lakeside Settlement of Dispilio, notes that future conservation technologies, such as nanotechnology-based stabilization, could better preserve such artifacts. The tablet’s survival, despite these challenges, defies the odds, standing as a testament to the resilience of Neolithic craftsmanship.

Debate on Writing’s Origins: A Battle of Interpretations

The Dispilio Tablet has ignited a contentious debate about the origins of writing. Hourmouziadis championed the idea that its markings constitute a script, potentially making it the world’s oldest written record. If true, this would shift the timeline of literacy back by 2,000 years, predating Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs, both dated to around 3100 BCE. Hourmouziadis argued that the symbols’ arrangement suggests a deliberate system, possibly for communication or record-keeping, aligning with the Neolithic transition to settled, agricultural societies that required new forms of documentation.

Critics, however, remain skeptical. The markings lack the repetition and structure typical of a phonetic script, such as consistent signs for sounds or words. Some scholars, as noted by Merlini in An Inquiry into the Danube Script (2009), propose they are symbolic rather than linguistic, perhaps used in rituals or to mark ownership. Merlini’s work on the Danube Script, a system of symbols from the Vinča culture, provides a comparative framework, but the Dispilio symbols are far older, leaving their connection uncertain. The debate mirrors broader discussions about early writing, such as the Tartaria Tablets (5300 BCE), which also face scrutiny over their status as script. The tablet’s ambiguity defies easy categorization, challenging scholars to expand their definitions of literacy.

The implications of this debate are profound. If the Dispilio Tablet is writing, it suggests that Neolithic Europe developed literacy independently, long before Near Eastern influences. This would upend traditional narratives that place Mesopotamia as the cradle of writing, highlighting a more decentralized emergence of human communication. Even if symbolic, the tablet reveals a Neolithic capacity for abstract thought, pushing back the timeline of cognitive complexity in Europe. Its very existence dares us to question long-held assumptions about the evolution of human expression.

Legacy and Future Research: Unlocking a 7,200-Year-Old Secret

The Dispilio Tablet’s legacy lies in its potential to rewrite history. It challenges the conventional timeline of writing, suggesting that Neolithic societies were far more advanced than previously thought. Its discovery has inspired renewed interest in early European symbolic systems, prompting comparisons with the Vinča culture and the later Linear A script of Crete. The tablet also underscores the importance of organic artifacts in archaeology, as most Neolithic evidence, as wood, textiles and basketry rarely survives. Its preservation in Dispilio’s lakebed offers a rare window into a material culture that defies the passage of time.

Future research holds promise for unlocking the tablet’s secrets. Advanced technologies, such as AI-assisted pattern analysis, could identify recurring symbols or structures, shedding light on whether they form a script. Machine learning models, trained on known early writing systems, might detect patterns invisible to the human eye, as suggested by ongoing studies in digital archaeology. Additionally, isotopic analysis of the wood could trace its origin, revealing more about Dispilio’s environment and resources. Collaborative efforts between linguists, archaeologists, and technologists are crucial to deciphering the markings, potentially confirming Hourmouziadis’ hypothesis of early literacy.

The tablet’s cultural impact extends beyond academia. It has become a symbol of Greece’s Neolithic heritage, drawing visitors to the Dispilio museum and reconstructed settlement. Educational programs at the site highlight its significance, fostering public appreciation for early human innovation. The tablet’s defiance lies in its mystery, refusing to yield its meaning easily, yet inspiring a quest for knowledge that bridges millennia. It stands as a call to action, urging us to explore beyond assumptions and embrace the complexity of our Neolithic ancestors.

Conclusion: A Defiant Voice from 5200 BCE

The Dispilio Tablet, etched with 7,200-year-old symbols, stands as Neolithic Greece’s defiant enigma. Discovered in the stilted village of Dispilio, its markings challenge the timeline of writing, hinting at a lost literacy that predates Sumer by millennia. Whether a script or symbolic code, it reveals a Neolithic society capable of profound abstraction, defying simplistic views of prehistory. Preserved against the odds, it demands rigorous study. This can be provided by AI analysis and or isotopic tracing, to unlock its secrets. From Lake Orestiada’s shores, the tablet calls us to hear a 5200 BCE voice, one that refuses to fade into history’s shadows.

References

- Hourmouziadis, G. (2002). Dispilio: 7500 Years After. Thessaloniki: Aristotle University Press.

- Fakorellis, G., & Maniatis, Y. (2000). “Radiocarbon Dating of the Dispilio Settlement.” Radiocarbon, 42(3), 411–418.

- Merlini, M. (2009). An Inquiry into the Danube Script. Sibiu: Editura Altip.