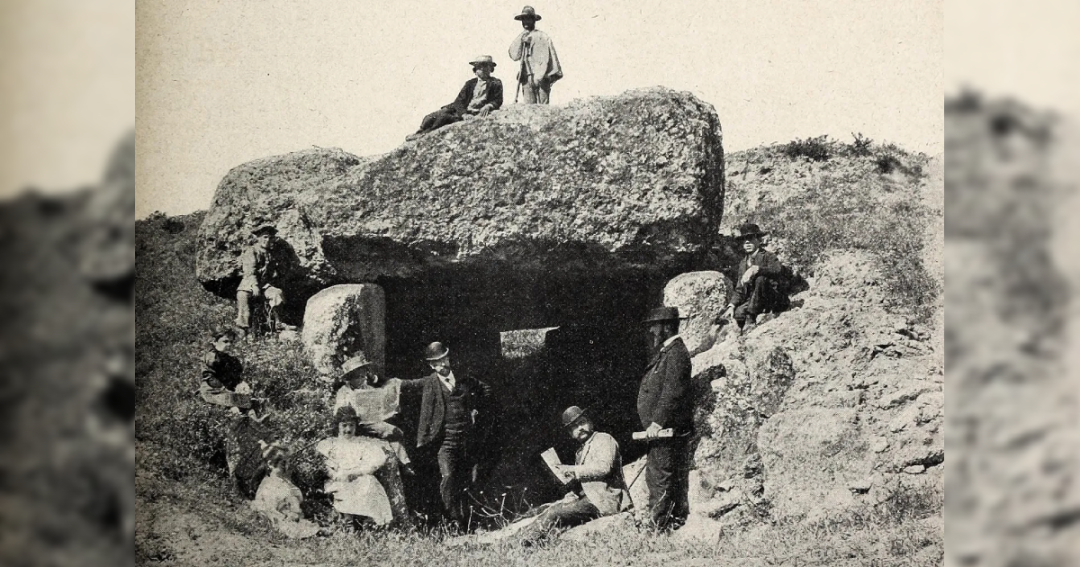

The so-called “Dolmen of Menga” on the Iberian Peninsula in Antequera, Spain was acknowledged as a groundbreaking discovery shortly after the first explorations were undertaken in the 1840’s.

Dolmen of Menga: Design

With the originality of design, three pillars aligned with the central axis of the monument, and the massive size of the orthostates and capstones. Mengas extraordinary dimensions demanded sophisticated design and planning, a large mobilization of labor, as well as perfectly executed logistics.

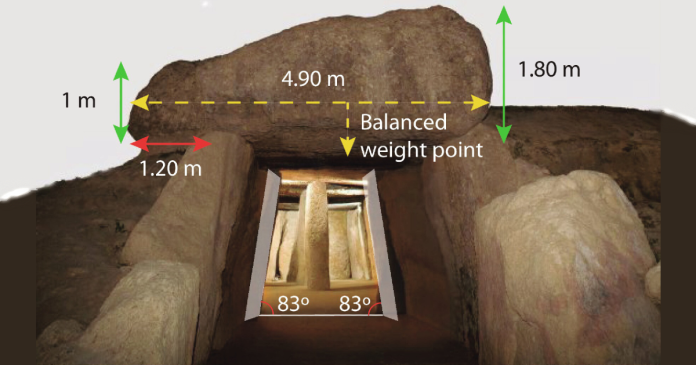

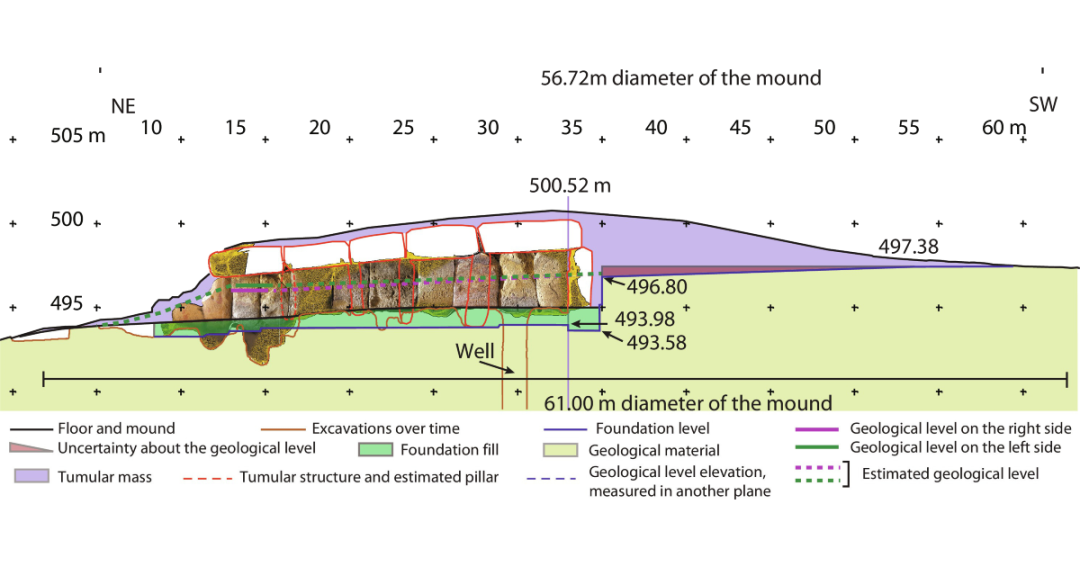

Inside Menga, observers quickly notice that the uprights (orthostats) lean inward rather than standing perfectly vertical. On average, they tilt at 85.2 ± 1.6° on the left side and 84.0 ± 2.0° on the right, measured against the horizontal floor. This inward tilt creates a trapezoidal cross-section within the dolmen.

In addition to leaning inward, the orthostats also tilt sideways against one another. On both sides of the dolmen, their angles measure 80°, 86°, and 88°, averaging 87.1 ± 2.4° on the left and 88.0 ± 1.9° on the right. These tilt patterns help researchers determine the sequence of stone placement and reconstruct the monument’s construction process.

Dolmen of Menga: Construction

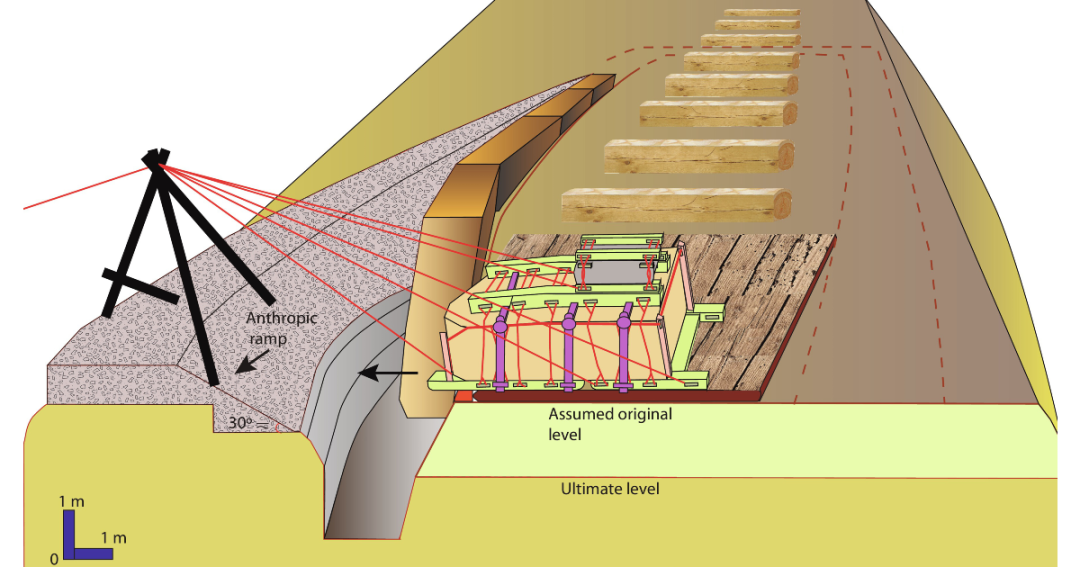

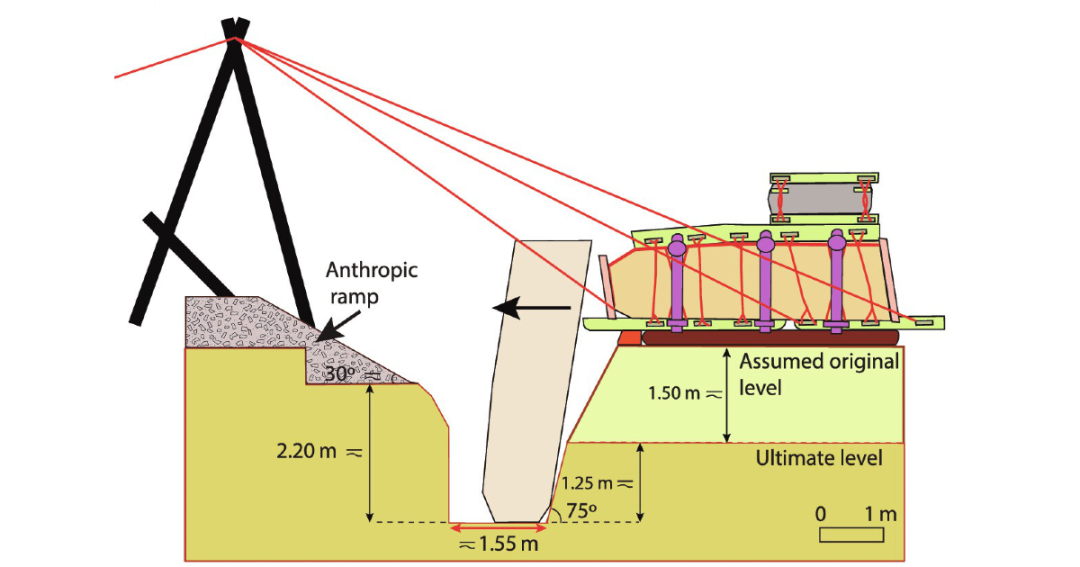

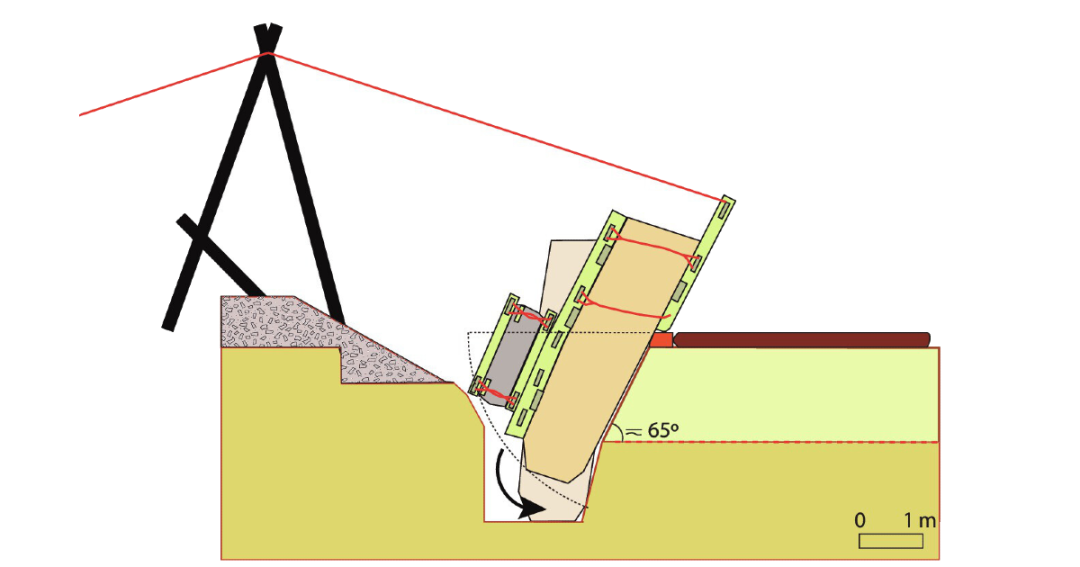

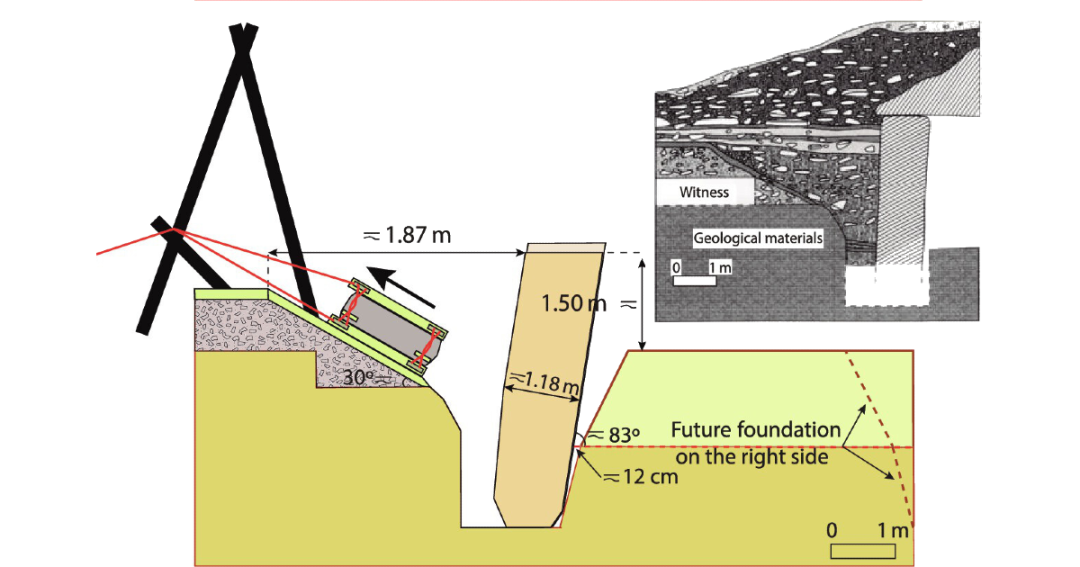

The placement of the stones at Menga reveals the ingenuity and engineering skill of its builders. They carved deep foundation sockets so that one-third of each upright would stand underground. This design strongly suggests they used counterweights to position the massive pillars with precision.

This technique, aimed at achieving a smooth and gradual tilting of the stones into the sockets, was crucial for two reasons.

1. This allowed for the placement of the stones with millimetric precision, both inside the sockets & with the adjacent stone.

2. It avoided the use of external descending ramps.

Several clues suggest that the uprights in Menga were dragged and placed from the inside out, not from the outside in, as previously thought.

Dolmen of Menga: Reconstruction

Engineering reconstruction has conclusively shown that the placement of large stones is more efficient when the gravity point shifts gradually with the help of a moving counterweight. This procedure achieves a smoother tilting of the stone into its socket.

With this construction method, it was possible to achieve a near-perfect adjustment of the orthostats to each other. This explains the precise and regular angle at which they are positioned. The uprights created two strong “walls” to support the massive capstones. The trapezoidal orthostats “locked” with one another downward and upward forming a solid and lasting stone assemblage. No other monument built at that time shows that type of design.

One striking feature of Menga’s design is the way much of the structure was carved directly into the bedrock. Researchers from the universities of Málaga and Granada documented this for the first time in the monument’s 200-year research history. They confirmed it through detailed analysis of excavation plans, photographs, and inferred topographic levels.

Builders embedded the front uprights of the dolmen (O-1 and O-23, beneath capstone C-1) about 2.75 meters into the bedrock, placing roughly one-third of each stone underground. Toward the back of the chamber, uprights O-11 and O-13 (beneath C-5) sit even deeper—around 3.20 meters. This “box-like” design anchors the structure directly into the bedrock, ensuring complete stability.

Megalith Longevity

Another important element to understand the prolonged persistence of Menga is the durability of the tumular structure. The dolmen builders created an insulating mound that keeps the interior of the dolmen perfectly dry. This insulation is especially important because the highly porous rocks that compose the main support for the dolmen would suffer major weight changes and chemical and physical weathering due to water interaction.

The dolmen’s architects designed pillars strong enough to support the unstable rock above. They also accounted for the weight of the tumulus, as shown by the arch-shaped contour of capstone #5. This feature helps redirect vector forces from the center toward the edges, reducing structural stress. Making Menga the first human-built stone structure functioning as a discharge arch.

The Dolmen of Menga stands as a remarkable feat of ancient engineering and construction. Yet it also served as a sacred space for the people who built itan enduring place of worship shaped by care, effort, and spiritual purpose.