For years, Göbekli Tepe and Nevalı Çori stood as enigmatic outliers, two ancient sites in southeastern Turkey, adorned with haunting T-shaped pillars, that hinted at a level of sophistication we didn’t expect from humanity’s distant past. Göbekli Tepe, perched on a limestone ridge, was long seen as the “world’s oldest temple,” a ceremonial hub built by wandering hunter-gatherers over 11,000 years ago. Nevalı Çori, 40 miles away and now submerged in 1992 beneath the Euphrates, river due to the construction of the Atatürk Dam, was thought a curious echo; a smaller settlement with its own T-pillars, drowned before its secrets were fully told. But recent discoveries are stitching these sites together into a bolder tapestry: not mere isolated outposts, but fragments of a sprawling, organized civilization that thrived in Upper Mesopotamia during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic.

Göbekli Tepe’s Hidden Village

The game-changer at Göbekli Tepe came with the unearthing of domestic life. Excavations led by Dr. Lee Clare and the German Archaeological Institute since 2019 have peeled back layers of soil to reveal more than just ritual enclosures. Houses with stone foundations, cisterns for rainwater, and thousands of grinding tools for wild grains suggest a settled community, not just a pitstop for pilgrims. Dated between 9600 and 7000 BCE, this village, nestled among the famous T-pillars, shows people didn’t just worship here; they lived, ate, and planned their days under the shadow of their monumental creations. It’s a revelation that flips the old script: Göbekli Tepe wasn’t a temple with visitors, but a home with a heartbeat.

Nevalı Çori: The Submerged Precursor

Across the rolling hills, Nevalı Çori tells a parallel story; until the waters silenced it. Excavated in the 1980s and 1990s by Harald Hauptmann before its flooding in 1992, this site on the Euphrates boasted its own T-shaped pillars, eerily similar to Göbekli Tepe’s. But it wasn’t all ritual temples. Rectangular houses with thick stone foundations, some with underfloor channels for drainage or heating, housed a community from roughly 8400 to 8000 BCE. Life-sized limestone statues—a bare human head with a snake-like tuft, a bird; hint at a rich artistic tradition, while the oldest known domesticated einkorn wheat points to early farming experiments. Nevalı Çori wasn’t a fleeting camp; it was a place where people settled, innovated, and revered the same T-pillar motif that defines its famous neighbor.

The T-Pillar Thread

What binds these sites isn’t just proximity, it’s those towering T-shaped pillars, a signature unique to the Şanlıurfa region. At Göbekli Tepe, they’re carved with wild beasts, snakes, foxes, cranes—standing up to 18 feet tall, framing circular enclosures. At Nevalı Çori, they’re integrated into walls, some bearing human hand reliefs, echoing the same anthropomorphic motif. This isn’t coincidence; it’s a shared cultural DNA. The pillars, often interpreted as stylized human figures or ancestral guardians, suggest a common belief system, a thread weaving through the hills and valleys. Their construction, quarried from local limestone, hauled by sheer human grit, demanded coordination, skill, and a collective vision that transcends two lone settlements.

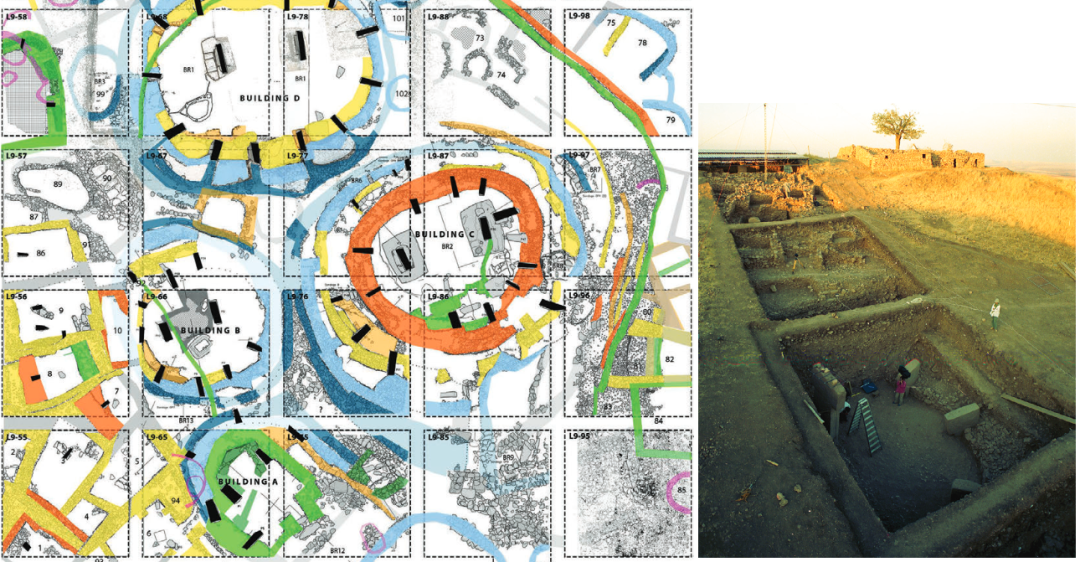

A Civilization in the Making

Imagine this: Göbekli Tepe and Nevalı Çori as nodes in a network, not solitary dots. The Taş Tepeler region—literally “Stone Hills”—is dotted with similar sites like Karahan Tepe and Taşlı Tepe, Kurt Tepesi, Harbetsuvan Tepesi, Hamzan Tepe, & Sefer Tepe, each flashing T-pillars like cultural beacons. Göbekli Tepe’s village, with its water management and food processing, mirrors Nevalı Çori’s domestic ingenuity, houses, early crops, and art. Together, they point to a society with division of labor: builders, carvers, farmers, and ritual leaders, all working in sync. The scale of their monuments, hundreds of workers fed and housed, as Klaus Schmidt once argued; implies a population bigger than a few scattered bands. This was a civilization, not in the urban sense of Sumer or Egypt, but in its social complexity, stretching across Upper Mesopotamia before pottery or metal entered the scene.

Why It Matters

Mainstream archaeology once pegged permanent settlements to agriculture’s rise, but these sites defy that timeline. Göbekli Tepe predates widespread farming, yet its dwellings suggest stability. Nevalı Çori, slightly later, bridges the gap with nascent wheat cultivation. Together, they propose a radical idea: social bonds, forged through shared rituals, monumental projects, and emerging villages, may have paved the way for farming, not the reverse. Their T-pillars, standing like sentinels, indicate a people who didn’t just survive but dreamed big, leaving a legacy now split between dry land and a watery grave.

A Lost World Reclaimed

Nevalı Çori’s drowning is a tragedy, its full story locked beneath the Euphrates, but Göbekli Tepe’s new finds offer a lifeline. As excavations continue, each house and tool uncovered could echo what’s lost, linking these sites into a coherent whole. They weren’t isolates; they were kin, part of a prehistoric civilization that flourished, built, and believed together. From Göbekli’s buzzing village to Nevalı’s sunken homes, we’re glimpsing the dawn of something greater; a society that didn’t just pass through history, but shaped it, one T-pillar at a time.

For more evidence on what makes Şanlıurfa region the key to a lost civilization read Megaliths and Metallurgy: A Lost Civilization Takes Shape