The construction of Khufu’s Great Pyramid has long been a subject of intense debate. Scholars, engineers, and independent researchers have all attempted to reconcile the monument’s extraordinary precision. Combined with the logistical constraints of the Fourth Dynasty. For decades, mainstream Egyptology favored large external ramps or combinations of straight and spiral ramps, despite the absence of archaeological evidence for such massive structures and the physical inefficiencies they would impose.

Into this landscape, Jean‑Pierre Houdin introduced a comprehensive construction theory that reinterpreted the pyramid’s internal architecture as an integrated system of ramps, mechanical devices, and structural innovations. His work, spanning multiple technical papers and detailed architectural analyses, offered a complete construction sequence from quarry to capstone. It explained not only how the pyramid was built but why its internal features take the forms they do.

The Grand Idea

In late 2025 a peer reviewed paper by Simon Andreas Scheuring presented a counterweight based construction idea for the Great Pyramid. The study frames the idea as a new mechanical interpretation. Yet the central mechanism was introduced almost twenty years earlier by Jean Pierre Houdin. Houdin showed the Grand Gallery as a counterweight ramp. His work included structural analysis and microgravimetry data. It also included a full architectural reconstruction.

Scheuring repeats the same core elements. These include the Grand Gallery, the Ascending Passage, the Descending Passage, and the space known as the portcullis antechamber. The study frames the chamber as a pulley like lifting system. The overlap is clear. The lack of citation raises questions about credit and the treatment of outsider research.

This article examines Scheuring’s hypothesis in detail and places it beside the complete construction theory developed by Jean Pierre Houdin. It documents the points of overlap between the two models and shows how Houdin’s earlier work already established the core mechanism. It also identifies the real differences between the approaches and considers what this moment means for the wider discussion about pyramid construction.

Scheuring’s Hypothesis

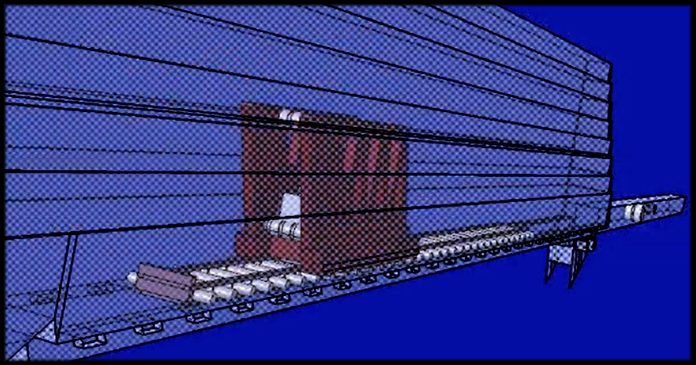

Sliding Ramp

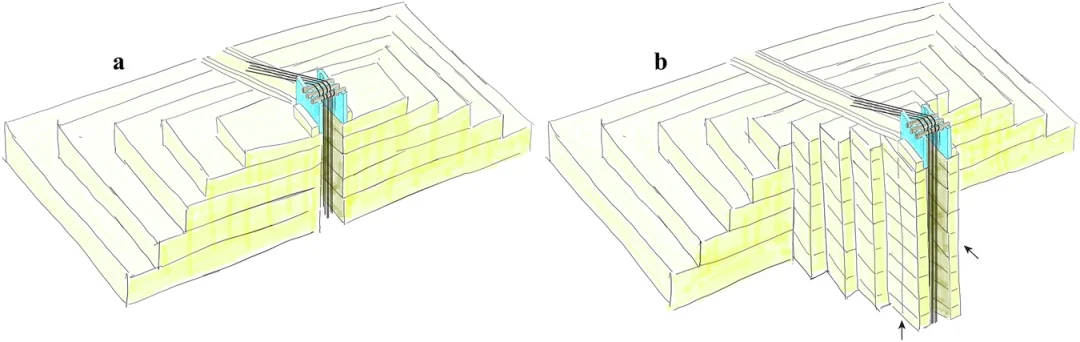

Scheuring’s model begins with the claim that the internal design of the Great Pyramid is mechanical rather than ceremonial. He argues that the Grand Gallery and the Ascending Passage form a continuous sliding ramp suited for force generation through a descending counterweight. In this view, wooden sledges loaded with stone or ballast slide down the Gallery and pull blocks upward. To support this motion, the model introduces vertical shafts in front of the Queen’s Chamber and the King’s Chamber. These shafts are not documented in any survey or scan and exist only inside the model.

Recasting the Antechamber

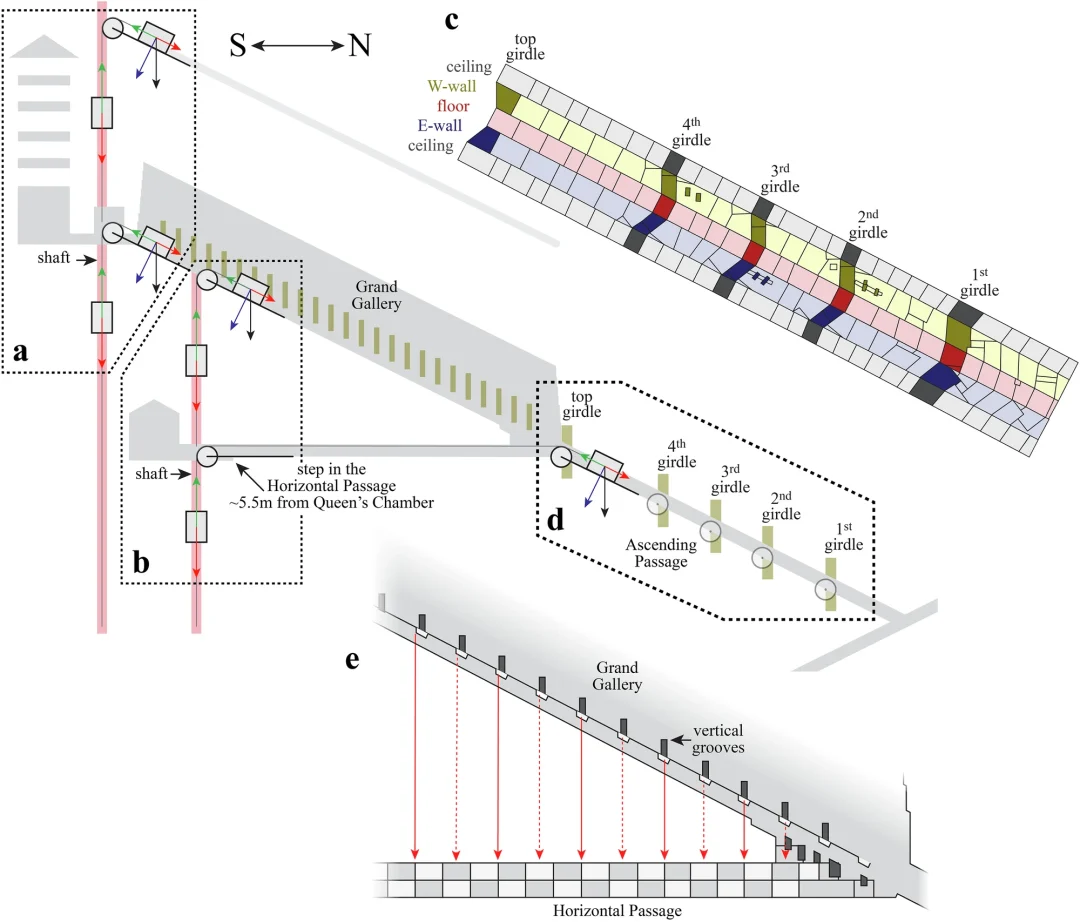

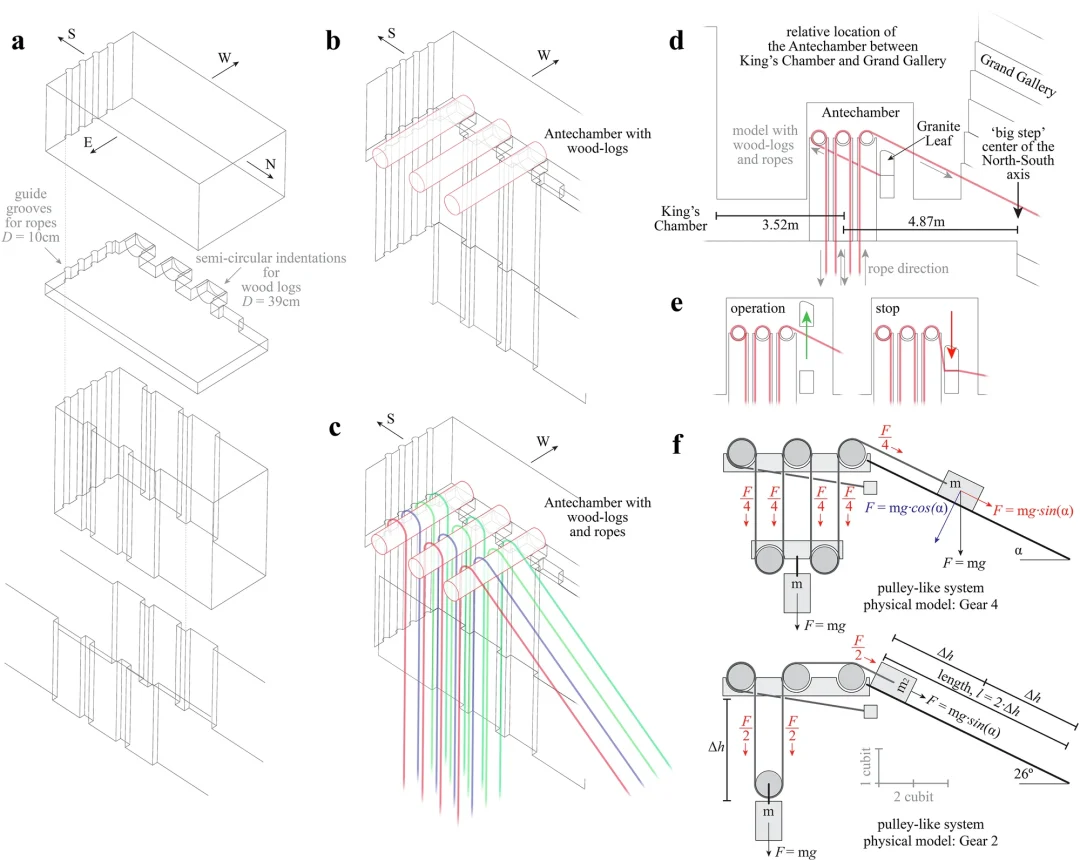

The portcullis antechamber is recast as a rope control room with channels and wooden logs that reduce friction. The Descending Passage is treated as an early or alternate sliding ramp inside a larger mechanical system. These are mechanical interpretations of existing architectural features.

A Unified Machine

Scheuring presents the internal spaces as parts of a single lifting machine. The Grand Gallery becomes a sliding track. The Antechamber becomes a pulley like device. The Ascending Passage becomes a force transmission corridor. The vertical shafts become lifting conduits inside the model. It claims that this system could raise the sixty ton granite beams of the King’s Chamber by using multiple rope folds to divide the load. It also claims that the pyramid grew in vertical shafts and sliding ramp spurts. This staged growth is not supported by direct evidence and is introduced to support the mechanical idea.

Limits of the Model

The paper is ambitious in its mechanical modeling. It attempts to reinterpret several architectural features through the idea of mechanical advantage. It presents the pyramid as a dynamic workspace rather than a static ceremonial monument. Yet the scope of the model is narrow. His hypothesis focuses on the internal passages and does not address the full construction sequence. External logistics are not addressed. Theirs no mention of structural engineering for the relieving spaces. Architectural inheritance from Sneferu is absent. It is an internal mechanical hypothesis, not a complete construction theory.

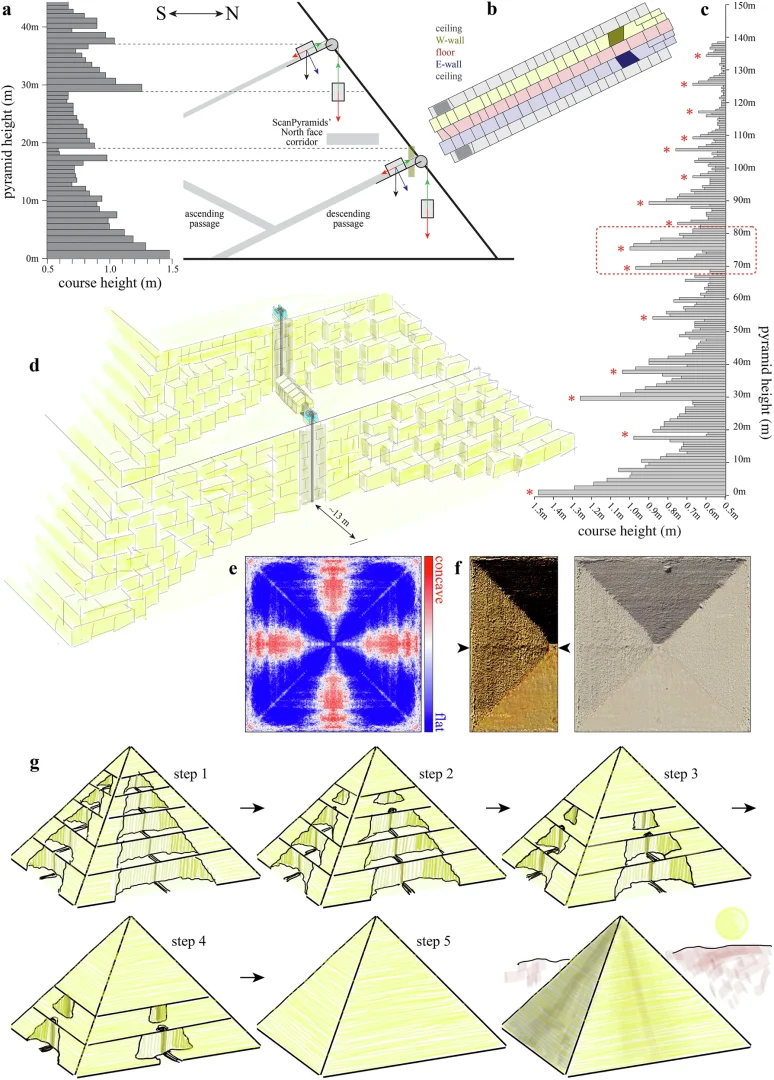

Houdin’s Construction Theory

Jean Pierre Houdin’s work, developed over more than a decade and documented in several technical papers, presents a complete construction theory that joins architecture, engineering, logistics, and structural analysis. He proposes that the pyramid was built with an external ramp for the lower third and an internal ramp for the upper two thirds. The internal ramp spirals upward inside the pyramid and turns at a series of ninety degree staging chambers. One of these chambers was later rediscovered and is now known as “Bobs Room”. This ramp system explains the concavity of the pyramid faces. It also explains the microgravimetry anomalies, the pattern of internal voids, and the architectural inheritance from the pyramids of Sneferu.

Central to Houdin’s theory is the use of the Grand Gallery as a counterweight machine. He interprets the notches, holes, and corbelled walls of the Gallery as evidence of a wooden framework that supported a sliding counterweight used to lift the massive granite beams of the King’s Chamber. Houdin’s analysis of the the portcullis chamber identifies rope grooves and mechanical features consistent with a lifting system. His work integrates the relieving chambers, the chevron structures, the microgravimetry anomalies, the predicted voids above the Gallery, and the predicted corridor behind the chevrons. It explains the structural logic of the King’s Chamber, the need for multiple granite ceilings, and the sequence in which these elements were constructed.

Houdin’s theory is not limited to the internal passages. It encompasses the entire construction process, from quarrying and transport to the placement of the final casing stones. He explains the architectural layout, the structural reinforcements, the mechanical devices, and the logistical flow of materials. It is a complete model of how the pyramid was built.

Overlapping Concepts and the Question of Attribution

The overlap between Scheuring’s model and Houdin’s earlier work is substantial and specific. Both theories identify the Grand Gallery as a functional mechanical space rather than a ceremonial corridor. They equally argue that its slope and architecture are ideal for a counterweight system. Both interpret the notches and grooves in the Gallery as evidence of wooden beams or mechanical supports. Each propose that heavy blocks were lifted using a counterweight sliding down the Gallery. Both reject the feasibility of large external ramps for the entire construction.

These are direct parallels in the interpretation of the same architectural features. The Grand Gallery as a counterweight ramp is the signature idea of Houdin’s theory. It is the innovation that made his work revolutionary. It is the mechanism that explains the placement of the granite beams, the structural logic of the relieving chambers, and the mechanical features of the portcullis chamber. Scheuring’s model adopts this mechanism as its foundation.

Glaring Omission

Yet Scheuring’s paper does not cite Houdin’s work. This absence is notable, especially given the prominence of Houdin’s theory in both academic and public discussions of pyramid construction. Houdin’s work was widely published, presented at conferences, supported by Dassault Systèmes, and documented in multiple technical papers. It is implausible that Scheuring, who clearly studied the internal architecture in depth, was unaware of it. Even if he had been, the scholarly norm would still be to acknowledge prior work once it is pointed out. The paper does not do so.

The absence of citation raisee questions about academic rigor and the treatment of outsider research. Houdin’s theory, though comprehensive and technically detailed, originated outside traditional Egyptology. Scheuring’s paper, published within a mainstream scientific journal, presents a narrower mechanical model that incorporates Houdin’s central mechanism without acknowledgment. This dynamic reflects a broader pattern in academia in which outsider ideas are dismissed until they are repackaged within institutional frameworks.

Where Scheuring’s Model Differs from Houdin’s

Despite the overlap, there are genuine differences between the two models. Scheuring’s hypothesis focuses almost exclusively on the internal passages and their mechanical reinterpretation. It does not attempt to explain the full construction sequence, the external logistics, the structural engineering of the relieving chambers, or the architectural inheritance from Sneferu. It presents the pyramid as a single integrated lifting machine rather than a combination of ramps, mechanical devices, and structural innovations.

Scheuring’s reinterpretation of the portcullis chamber is one of the more original aspects of his model. He treats it as a pulley like mechanism with rope channels and wooden logs that reduce friction. Houdin also identified mechanical features in this chamber, but his interpretation is integrated into a broader construction sequence rather than a standalone mechanism. Scheuring’s model also introduces the idea of vertical shafts used for lifting, though these shafts are speculative and not supported by direct archaeological evidence. Houdin’s theory does not rely on vertical shafts for lifting but instead uses the internal ramp and the Grand Gallery counterweight system.

These differences do not negate the overlap in the core mechanism, but they do represent genuine divergences in the interpretation of specific architectural features.

Assessment of Co‑Option and Innovation

The question of whether Scheuring co‑opted Houdin’s ideas without credit is not a matter of personal accusation but of scholarly analysis. The central mechanism of Scheuring’s model, the Grand Gallery as a counterweight ramp, is identical to the mechanism introduced by Houdin. The mechanical interpretation of the Gallery’s architecture, the use of sliding counterweights, the reinterpretation of the portcullis chamber’s rope grooves, and the rejection of large external ramps all originate in Houdin’s work. These elements form the foundation of Scheuring’s model.

At the same time, Scheuring introduces new mechanical interpretations, particularly in his treatment of the portcullis chamber and the Descending Passage. His model is narrower in scope but attempts to reinterpret the internal passages as a single integrated lifting machine. These contributions represent genuine innovation within the limited framework of his hypothesis.

Scheuring’s model builds upon Houdin’s foundational insight without acknowledgment, but it also introduces new mechanical interpretations that differ from Houdin’s broader construction theory. The issue is not whether Scheuring’s model is entirely derivative but whether it properly situates itself within the existing body of research. On that point, the absence of citation is a significant omission.

Implications for the Future of Pyramid Studies

Scheuring’s paper marks a significant moment in the academic conversation about pyramid construction. For the first time, a counterweight based construction model has been published in a major peer reviewed scientific journal. This development brings counterweight theories into mainstream academic discourse and validates the mechanical interpretation of the Grand Gallery that Houdin introduced nearly two decades earlier.

If Scheuring’s model gains traction, it may encourage new archaeological investigations into predicted shafts, inspire mechanical reconstructions or simulations, and prompt a reevaluation of the pyramid’s internal architecture. It may also lead to a broader recognition of the mechanical sophistication of Old Kingdom engineering.

At the same time, the moment highlights the need for proper attribution and the integration of outsider research into academic frameworks. Houdin’s theory, though developed outside traditional Egyptology, remains the most comprehensive and technically detailed construction model of the Great Pyramid. His work deserves acknowledgment not only for its originality but for its influence on subsequent research.

Conclusion

The Great Pyramid remains one of humanity’s most extraordinary engineering achievements, and the debate over its construction continues to evolve. Scheuring’s counterweight based model is a narrow but ambitious mechanical reinterpretation of the internal passages. It shares substantial conceptual overlap with Jean‑Pierre Houdin’s earlier and far more comprehensive construction theory. While Scheuring introduces new mechanical ideas, his model builds upon Houdin’s foundational insight without acknowledgment.

Scheuring’s paper brings counterweight based construction into mainstream academic discourse, but it does so by adopting the central mechanism of Houdin’s theory without credit. Houdin’s work remains the most expansive and detailed construction model of the Great Pyramid, and its influence is evident in the very ideas that Scheuring presents as new.

The future of pyramid studies will likely involve a synthesis of mechanical modeling, architectural analysis, and archaeological investigation. As counterweight based theories gain mainstream acceptance, it is essential to recognize the contributions of those who laid the groundwork. In that sense, the mainstreaming of counterweight construction is both a validation of Houdin’s insight but also a reminder that the walls surrounding mainstream research are still too high. And the people inside them too insular.