Rethinking the Hobbit

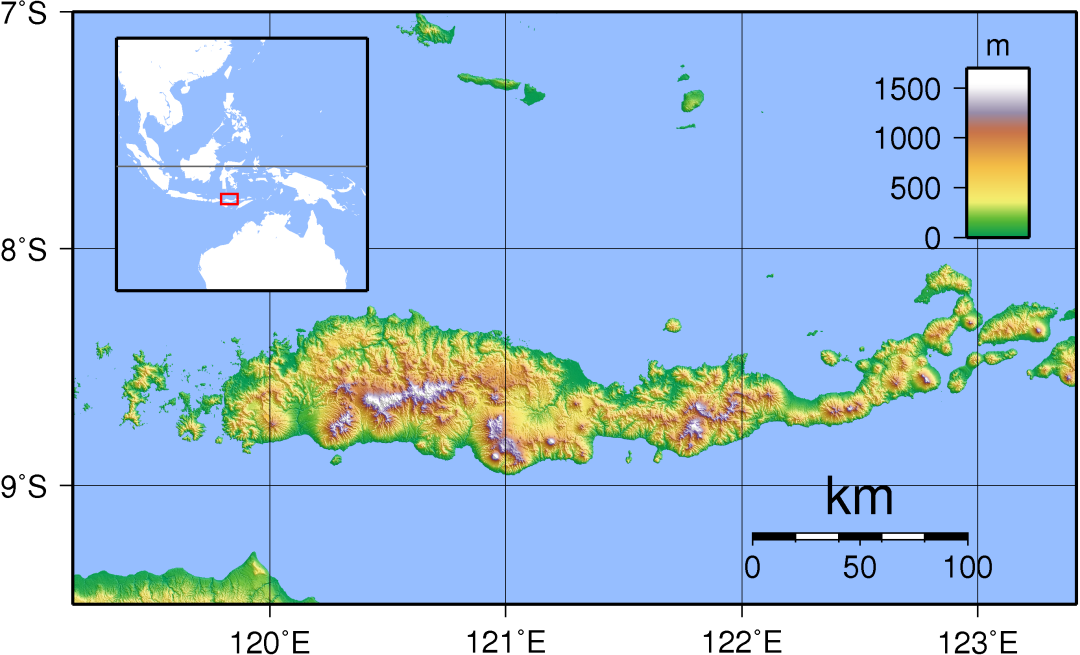

In the deep caverns of Liang Bua on the Indonesian island of Flores, a discovery was made in 2003 that rattled the scaffolding of human evolutionary theory. The partial skeleton of a diminutive hominid, standing just over a meter tall, was unearthed alongside stone tools, animal bones, and the traces of an ancient fire. Named Homo floresiensis, and affectionately dubbed “the Hobbit,” this small being forced paleoanthropologists to confront questions they were scarcely prepared to ask.

From the outset, Homo floresiensis was treated as an anomaly. Its small stature, limited brain volume, and seemingly archaic features were so incompatible with the established linear view of human evolution that many scientists rushed to classify it as pathological. Surely, they argued, this was a diseased modern human. Perhaps a case of microcephaly or dwarfism. Something abnormal rather than a distinct and intelligent lineage of the genus Homo.

But what if the real problem was not the fossil, but the lens through which it was being viewed?

The prevailing paradigm of human evolution, still tethered to nineteenth-century progressive ideas, tends to place modern humans at the apex. One that sees a pinnacle of intelligence and complexity. In this framework, any deviation from the standard Homo sapiens mold must be a defect, not a difference. Yet the bones found in Liang Bua may tell a different story, one of survival, adaptation, and intelligence manifested in unfamiliar form.

What if Homo floresiensis was not a failed offshoot, but a successful specialist? What if, rather than being a victim of pathology, it was an example of nature’s precise engineering. One that created a kind perfectly to its environment, evolved for life beneath the earth, and perhaps as cognitively capable in its own way as any modern human?

In this article, we will follow the echoes of this controversial hominid across stone, soil, and scholarly discourse. We here explore the possibility that intelligence is not confined to a single blueprint, and that human history may be far more diverse, mysterious, and humbling than we have dared imagine.

The time has come to reframe the Hobbit. Not as a scientific curiosity, but as a legitimate member of the human family. A creature not of lesser mind, but of different wisdom. A being whose story deserves to be told without the filters of prejudice or the scaffolding of outdated models.

And so, we begin.

The Cave People of Flores

The limestone vaults of Liang Bua are more than a burial chamber for the bones of Homo floresiensis. They are a silent testament to the kind of life these beings once led. A life beneath the surface, beneath the assumptions of those who would later seek to define them. In these caves, the air is cool and still, immune to the volatility of tropical surface weather. The darkness they pierced with firelight, illuminating the tasks of living: toolmaking, food preparation, storytelling. This was not a refuge, for them, it was home.

For a long time, it was assumed that caves were marginal places, temporary shelters for the unlucky or desperate. Yet what the archaeology of Liang Bua tells us is quite the opposite. The stratigraphy reveals layers of continuous occupation, spanning thousands of years. Hearths, tools, and faunal remains speak of familiarity, not flight. The inhabitants were not merely hiding from a hostile world; they were thriving within a chosen one.

This subterranean existence was not accidental. In fact, it may have been one of the keys to their longevity. Living underground offered protection from predators, harsh weather, and volcanic events. We now know they were quite common in this geologically restless region. It also fostered social cohesion, demanding cooperation and memory in the absence of visual cues. If language was spoken here as there is reason to suspect it may have been, then it echoed from stone walls, shaped by the acoustics of their chosen dwelling.

Masters of Subterranean Survival

The body of Homo floresiensis, with his dark environments, short stature and unique limb proportions, makes more sense in this light. Compact, robust, and agile, this hominid may have moved through the cave’s uneven chambers with an ease that taller, more gracile humans could not match. Adaptation, in this case, was not merely survival, what we see is optimization.

Moreover, their decision to remain cave dwellers was likely not due to incapacity, but to ecological intelligence. The resources of Flores, particularly near Liang Bua, would have offered ample sustenance. Giant rats, Komodo dragons, and Stegodon (a now-extinct dwarf elephant) roamed nearby. The tools found alongside the fossils were fashioned with purpose, from volcanic rock, shaped and sharpened with intention.

These were not primitive creatures reacting blindly to nature. They were engineers of their own habitat. The cave was not a cage, but a canvas, a welcoming home. Those who lived within it, far from being mere relics of a bygone time, may have been among the most well-adapted humans to have ever lived on this planet.

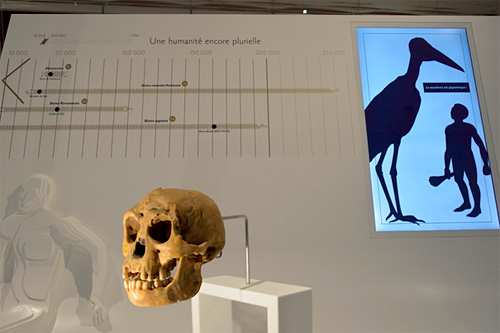

Intelligence Beyond Cranial Volume

For over a century, the size of the human brain has been used as a metric for intelligence. It is a model that has reinforced ideas of evolutionary superiority and shaped the way hominids are ranked on a presumed ladder of cognition. Yet Homo floresiensis presents a compelling challenge to this hierarchy. With a cranial volume of approximately 400 cubic centimeters, less than a third of modern humans, this small being should, by traditional standards, have been cognitively primitive. And yet, the evidence speaks otherwise.

The association of stone tools with Homo floresiensis remains among the strongest rebuttals to the brain-size fallacy. These were not crude implements. The flakes and cores unearthed in Liang Bua reveal a level of skill in lithic technology suggesting foresight, planning, and adaptability. The tools were effective, made with precision, and consistently replicated. Moreover, they were used in the butchery of large animals such as Stegodon. This was no small feat for a hominid, no matter its stature.

Toolmaking is not the only indicator. The archaeological layers suggest the controlled use of fire, further supporting the idea of symbolic cognition and technological mastery. Cooking, warmth, and light in a subterranean world would have been essential, not merely convenient. Fire implies communication, tradition, and memory passed through generations.

Modern Insights

Recent neurological studies support the view that intelligence is not simply a matter of scale. Brain organization, efficiency of neural pathways, and density of cortical structures all contribute to cognitive capabilities. It has been proposed that Homo floresiensis had a brain uniquely wired for its environment, perhaps not unlike some modern human populations whose brain-to-body ratio varies without any corresponding deficit in intelligence.

If anything, the tools, behaviours, and survival of this hominid point to a mind that was perfectly attuned to its context. His Mindscape was in perfect tune with its Landscape. Intelligence, then, must be redefined. It clearly is not as a singular trajectory toward complexity, but as an adaptive function expressed in diverse and context-specific ways.

In the case of Homo floresiensis, that intelligence was not written in brain mass, but in stone, fire, and survival. It was spoken, perhaps, in an ancient language that echoed through limestone halls and has yet to be translated.

Anatomical Sophistication

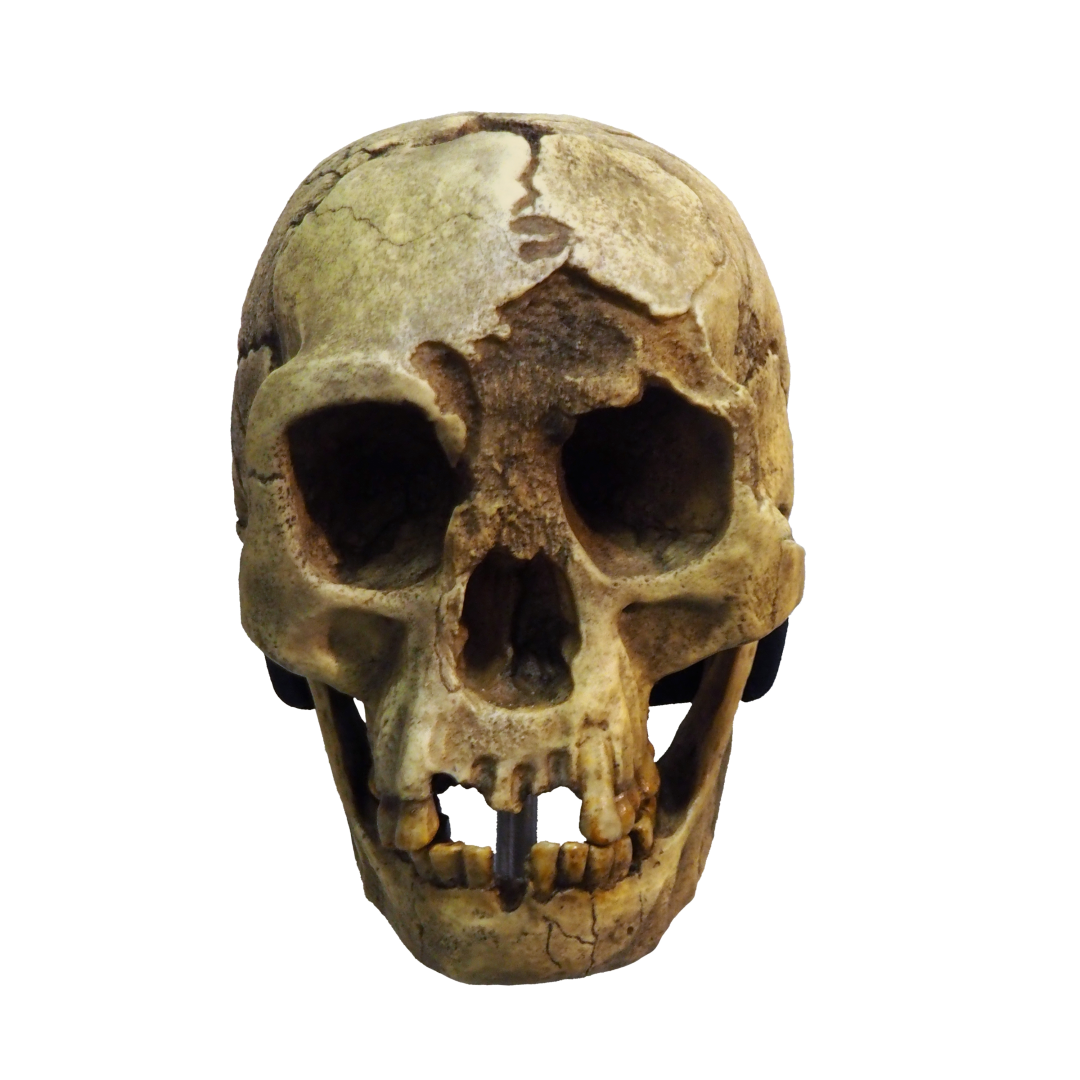

To understand Homo floresiensis fully, one must not only look at its skull, but also its body. The skeletal evidence reveals an individual, perhaps an entire population, that evolved not through degeneration, but through refinement. The Hobbit was not a stunted human. It was something different, and perhaps even something better suited to its world.

The limbs of Homo floresiensis are short yet strong, its feet proportionally long, and its pelvis broad. These features may initially appear primitive, but when viewed within the context of island adaptation, they emerge as signs of efficient engineering. Island dwarfism has been proposed as an explanation, and while the reduction in size fits such models, it fails to account for the entire picture. Notably, this body type also resembles earlier hominins, such as Homo habilis, suggesting a lineage that diverged early and developed along its own path.

Rather than viewing these traits as regressive, we might consider them purposeful. On an island of dense forest, sharp limestone, and volcanic instability, a smaller frame may have been a survival advantage. Less energy was required for movement and food. Agile climbing and crouched walking were essential. In this light, Homo floresiensis was not underdeveloped, but optimally designed.

Small but Sovereign

Furthermore, the wrist bones and shoulder structure bear similarities to both Australopithecus and early Homo, reinforcing the theory of a deep ancestral lineage. These were not malformed humans, no, they were part of a diverse mosaic of human evolution that never conformed to a linear model.

In redefining Homo floresiensis, we are asked to question not only what it means to be human, but also what it means to be evolved. The Hobbit, small as it may be, casts a long shadow across the assumptions of anthropology. It stands not in the margins, but in the center of a much larger and richer human story.

The Pathology Debate

Ever since researchers unveiled Homo floresiensis, debate has raged, not only about its place in the human family tree but also about its legitimacy as a distinct species. A number of voices in the scientific community sought to reduce this ancient lineage to a medical footnote. They claimed that the skeletal remains found in Liang Bua were not evolutionary cousins but pathological modern humans. The primary theory? That LB1, the holotype of Homo floresiensis, was simply a microcephalic dwarf.

But such claims, while loud, have not held up under careful scrutiny.

At the heart of the argument lies brain size. With a cranial volume of approximately 400 cubic centimeters, LB1’s brain was unquestionably small. Deniers like Professor Teuku Jacob and Robert Martin argued that this matched the profiles of modern humans afflicted by microcephaly. This condition involves abnormally reduced brain size along with physical impairments. Researchers used photographs of the Rampasasa people. These lived near Liang Bua and are typically smaller in stature. They cited receding chins and facial asymmetries as signs of pathology

However, these comparisons collapse when met with the full weight of the anatomical data.

Misreading the Evidence

The mandibles of Homo floresiensis, both LB1 and the later-discovered LB6, lack the defining chin structure of Homo sapiens, including the “inverted T” formed by the lower ridge and midline. Instead, they bear internal buttressing more in line with earlier hominids like Homo habilis. This structural divergence cannot be explained by disease. No known pathology can account for the consistent appearance of primitive features across multiple individuals, separated by tens of thousands of years.

Moreover, extensive analysis of modern microcephalic skulls has revealed stark differences from LB1. Studies by Falk et al. demonstrated that the brain shape and structure of the Hobbit, though small, was proportionally normal, suggesting a brain that was not diseased but miniaturized and functionally adapted.

The asymmetry of the skull, another key point raised by sceptics, clearly shows resulting from post-mortem distortion and excavation damage. When digitally reconstructed, the skull of LB1 exhibits far more symmetry than early critics admitted. The archaeological layers themselves undermine the pathology theory: nine individuals, spanning a period of over 60,000 years, all sharing the same diminutive dimensions. Is it likely that an entire population suffered the same rare condition and left no trace of unaffected individuals? I believe not.

Conclusion

The pathology debate has revealed more about the biases within the field than about the bones of Flores. The rush to pathologize reflects a deeper discomfort with diversity in human form. A resistance to the idea that intelligence, capability, and humanity can emerge in unfamiliar packages. To the fact that Panspermia is far likely a better creation mechanism than evolution. That there is a variety of created Hominid beings that although fused in the vast ages of the world, were created individually, for different purposes, for different environments.

In the story of Homo floresiensis, the true abnormality lies not in the fossil record, but in the assumptions used to interpret it.