A Palaeolithic Gallery Unveiled

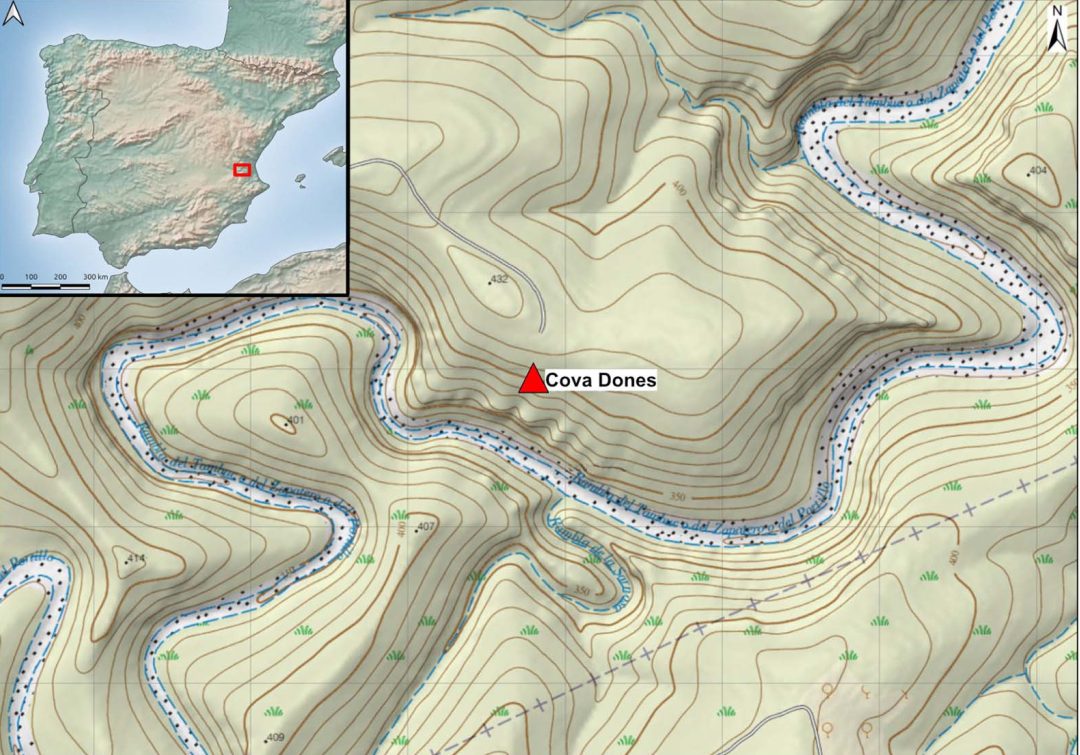

Imagine a steep canyon in the heart of Valencia, where the earth splits to reveal a single-gallery cave stretching 500 meters deep, its mouth a portal to a world untouched by the sun’s full reach. This is Cova Dones, nestled in Millares at 399 meters above the sea. Its coordinates etched as 30S 692764X 4338785Y in the unyielding grid of UTM. For ages, it stood silent, known only for a scattering of Iron Age relics, namely pottery and tools from a later folk.

First catalogued by Aparicio in 1976. His work that continued until the summer of 2021. When an informal wander through its depths uncovered something extraordinary. Four painted motifs, among them the proud head of an aurochs gazing from the rock. That glimpse, found by chance, sparked a fire. By 2023, Aitor Ruiz-Redondo, Virginia Barciela, and Ximo Martorell had named it a major Palaeolithic art site. A sanctuary of the Pleistocene unlike any known along Iberia’s eastern coast.

Marks of Man

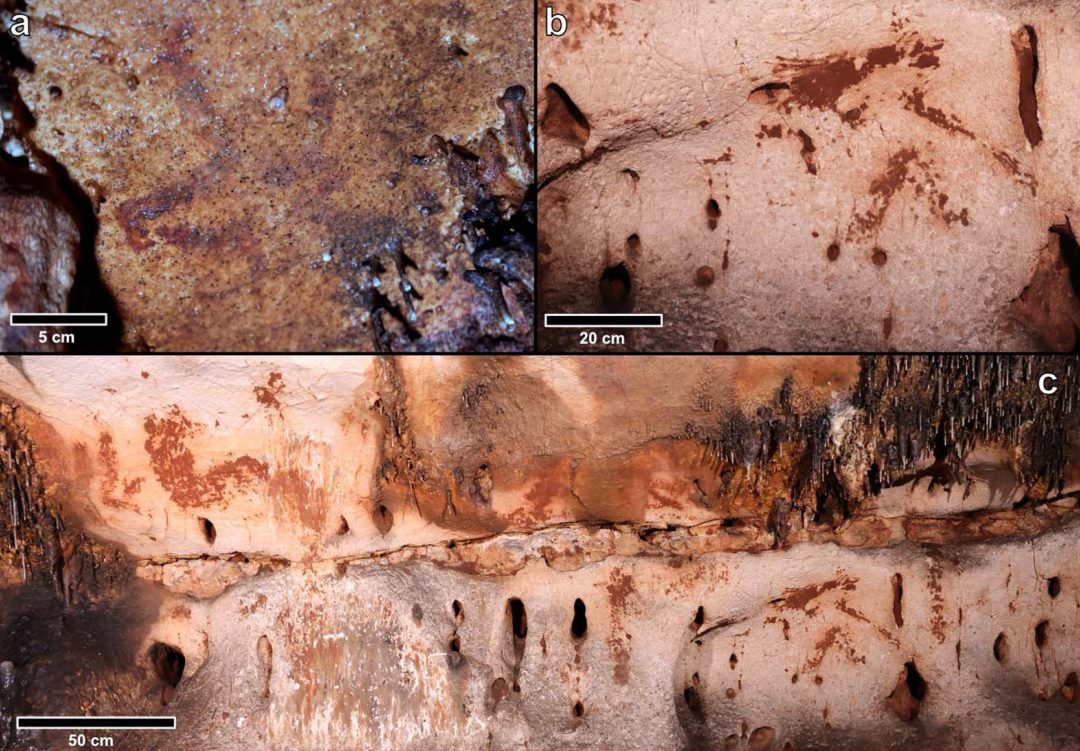

What do we find within these walls? More than 110 graphic units, as they call them. Marks of human intent scattered across three zones, each reachable without a climb. Even 400 meters from the entrance where the cave’s heart beats strongest. Nineteen of these are animals, clear as memory allows. Seven horses, their manes flowing in stillness. Seven hinds, female red deer graceful in their lines. Two aurochs, massive and horned; a stag, antlers proud; and two beasts too worn to name. Beyond these zoomorphs lie signs, rectangles and meanders etched with purpose. Panels of ‘macaroni,’ those finger-drawn flutings across soft surfaces, and lines that stand alone or fade into mystery. It’s a gallery vast and varied. A canvas of the Upper Palaeolithic that defies the scarcity of such art in this corner of the Mediterranean.

This isn’t the Franco-Cantabrian core, where seven in ten Pleistocene art sites cluster, nor the southern fringes of Spain or Italy that dot the edges of that heartland. Eastern Iberia has long been a paradox. Home to Parpalló, a cave rich with mobiliary art, its thousands of decorated slabs a testament to ancient hands, per Villaverde in 1994, yet stingy with parietal art. Before Cova Dones, only nine caves here bore certain Palaeolithic markings, perhaps 21 if you stretch the possibles, per Villaverde’s 2020 tally. Painted figures? A mere three, at best, across Valencia and Catalonia combined. So when Cova Dones yielded this bounty, it shifted the ground beneath us, a sudden flood of light on a coast thought dim.

Why Cova Dones is Unique

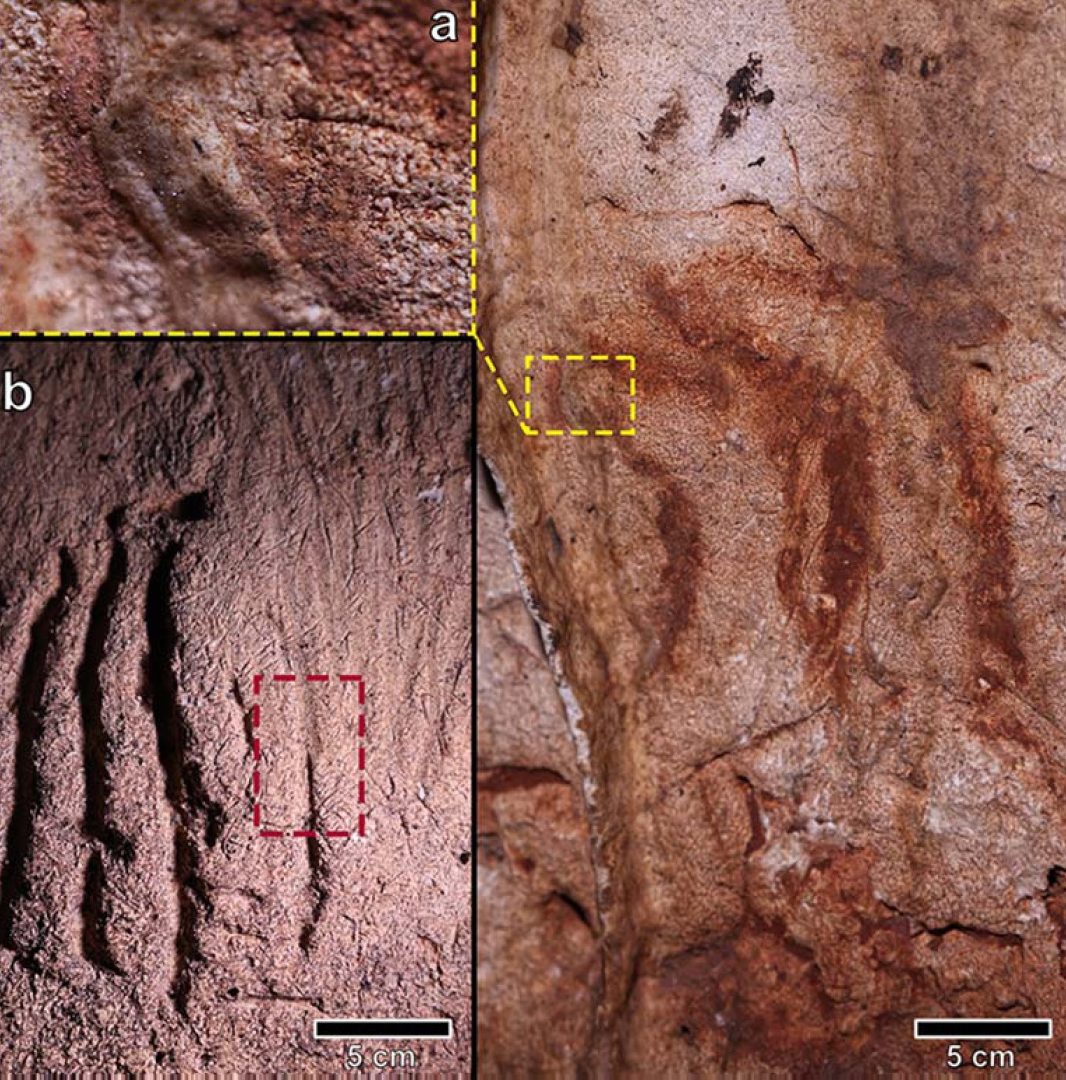

What sets this place apart isn’t just the count but the craft. The engravings catch the eye first, some are simple, single-trait outlines, like the ‘Mediterranean trilinear hind’ with its three-line grace. A style known from Nerja to La Pileta, per Fortea’s 1978 gaze. Others surprise: figures shaded by scraping mondmilch, that soft limestone skin, a technique rare in Palaeolithic caves, unseen before in eastern Iberia.

Two horse heads emerge this way, their forms carved from the wall’s own flesh, a method that whispers of ingenuity in the dark. Then the paintings, over 80 units, every one brushed with red clay, not the usual ochre or manganese dust diluted thin. This clay, iron-rich and plentiful on the cave’s floor, was smeared fresh onto stone, a bold choice known in spots like Ardales or Rouffignac but rare, save at La Baume Latrone. Here, it’s the rule, not the exception, a signature that marks Cova Dones as distinct.

including animals and signs (some partly covered by calcite layers)

Aging the Etchings

How old are these marks? Time’s a slippery thing in caves, where the clock ticks in calcite and patina, not neat years. The clay paintings defy easy dating, fresh when applied, they’ve dried in a damp world, some cloaked by thick calcite layers that shroud hinds and signs alike. That crust, slow to form, hints at age, a shield over art that’s stood for millennia. The ‘macaroni’ flutings, simple drags of finger or tool, are trickier still, their form’s too basic to pin down, though weathering suggests depth. But a clue sharpens the frame: cave-bear claw marks, scattered across the walls, one slicing over a fluting panel. Ursus spelaeus faded from Europe around 24,000 years ago, calibrated before present, per Terlato’s 2018 study, setting a boundary, these marks came before that end.

Style offers more. Those trilinear hinds echo Nerja, where a charcoal date from Sanchidrián in 2001, pegs a panel at 19,900 ± 210 years BP, calibrated to 24,545–23,680 BP with 85% certainty using IntCal20, a Gravettian-Solutrean cusp, 26,000 to 24,000 years ago. Rectangular signs, not common across the Upper Palaeolithic, match Parpalló’s mobiliary trove, dated to 24,500–21,100 BP by Villaverde and Cantó in 2020, aligning with Mediterranean peers like Comte and Ambrosio. The aurochs and horses, less diagnostic, lean pre-Magdalenian, older than 20,000 years, per Ruiz-Redondo’s team. Tie that to the bear’s exit, and we’re looking at art born before 24,000 years ago, Gravettian, perhaps, or earlier still, a whisper from the Pleistocene’s dawn.

Selective Placement

Why here, in this deep gallery? The cave’s no fortress, 500 meters long, single and straight, opening to a canyon’s edge, it’s a path, not a lair. Iron Age folk left their pots, per Aparicio, but Paleolithic feet were unseen until 2021. Accessibility matters: 400 meters in, the main panels greet you without a scramble, a stage set for those who dared the dark. The animals, meaning, horses, hinds and aurochs, mirror the prey and pride of a hunter’s world, yet the signs and flutings hint at more, a language we’ve lost. The clay, local and vivid, ties the art to this place, a bond of earth and hand. Scraping mondmilch, rare as it is, speaks of a mind at play, shaping what the cave gave. This isn’t Franco-Cantabria’s dense herd of bison or Italy’s sparse scratches, it’s a voice unique, a chorus from Iberia’s eastern flank.

Lone Cova Dones

What do we know beyond the cave? Eastern Iberia’s art was thin, Parpalló’s slabs, yes, but cave walls stayed mostly bare. Nine sure sites, per Villaverde, stretched from Catalonia to Valencia, with possibles pushing to 21, yet paintings were a whisper: three, maybe, before Cova Dones roared. The Franco-Cantabrian heartland, with its 70% share, per Ruiz-Redondo’s forthcoming work, long held the spotlight, but finds in Asia and southern Spain nudge us wider. Cova Dones joins this shift, a beacon on a coast thought silent, its 110 units dwarfing the region’s tally, its techniques, clay painting and mondmilch scraping, are new to this shore. Nearby, Cova de la Font Major hints at more, per Morales in 2022, but Dones stands tallest now, a giant among the sparse.

Absent Artists

Who made this? We see no bones, no hearths, just the art, speaking for hands lost to time. The Gravettian folk, 34,000 to 24,000 years back, roamed Europe, their tools and graves known from Parpalló to Nerja, per Villaverde’s 1994 dive. Hunters, they tracked horse and deer, their lives etched in flint and bone. The cave bear’s claw, overlapping flutings, ties them here before its end, a fleeting dance of beast and artist. Were they locals, rooted in this canyon, or wanderers from afar, drawn to its shelter? The clay says local, plucked from the floor, not hauled in, yet the trilinear hinds nod to a wider web, a style shared across Iberia’s Mediterranean arc.

Early Beginnings

What’s the meaning? Horses and hinds, Aurochs, two, and a stag, one, add weight, their bulk a challenge met. As Signs we find rectangles and meanders, these elude us, symbols of clan or cosmos, per Villaverde and Cantó, their kin at Parpalló dated deep. Flutings, finger-drawn, feel personal, a touch on soft stone, yet their overlap with bear marks roots them old. This isn’t narrative art, no scenes unfold within it, nothing but a gallery of presence, a claim on the dark. The techniques, the use of clay and mondmilch scraped, suggest experiment, a craft born here, or still to be found, for it remains rare elsewhere save in scattered echoes like Ardales or La Baume Latrone.

some finger flutings.

Where Does it Fit?

Where does this fit? Franco-Cantabria brims with art, remember the Altamira’s bison, or the Lascaux’s herds, these dated 36,000 to 12,000 BP, per Pike in 2012. Southern Spain’s Nerja, 42,000 BP at its oldest, per Sanchidrián, offers a counterpoint, yet eastern Iberia lagged, its caves quiet till now. Cova Dones bridges this, Gravettian, pre-24,000 BP, it aligns with Parpalló’s peak, per Villaverde, yet its parietal richness stands alone. The Mediterranean arc, Nerja and La Pileta, share hinds and signs, but Dones’ clay and scraping set it apart, a local twist on a shared tongue. Beyond Iberia, Asia’s Sulawesi, 45,000 BP, per Aubert in 2019, widens the map, making Pleistocene art a global hum, not Franco-Cantabrian alone.

More to Discover

What’s left to find? The team of Ruiz-Redondo, Barciela, Martorell, calls this the early days, per their 2023 Antiquity piece. Over 110 units found may hint at more, there are yet walls unsurveyed and shadows unlit. The clay’s age, calcite-sealed, begs dating, perhaps uranium-thorium on those layers. Flutings and signs need context, Parpalló’s slabs guide, but Dones’ walls demand their own voice. Archaeological traces like tools or bones, could flesh out the artists, though none surface yet. The Valencian Government backs this, per permit 2023/0075-V, and Zaragoza and Alicante fuel the quest, per their funding. Data lies open, they say, raw notes on request, a call to dig deeper.

Authors Notes

As we stare in Cova Dones’ gloom, these 19 beasts, including horses, hinds, and aurochs, stare back at us. Their gaze, 24,000 years cold, their makers not but dust. Clay paintings, mondmilch carvings, signs we can’t read, yet they challenge us: why this cave, this coast, this art? The bear’s claw, the calcite veil, pin them old, Gravettian or near, yet the why eludes. Were they marking home, honouring prey or speaking to spirits? Eastern Iberia, once sparse, now sings through Dones, its 110 marks a shout where whispers reigned. I see no answers, only questions, more walls to scan and more time to peel. As a final thought, we must also keep in mind that although we can identify the animals in these artworks, meaning what they are, we are still far from perceiving what they represent.

Bibliography:

- APARICIO, J. 1976. El culto en cuevas en la región valenciana. Revista de la Universidad Complutense 25 (101): 9–30. FORTEA, J. 1978. Arte paleolítico en el Mediterráneo Español. Trabajos de Prehistoria 35: 99–149.

- MORALES, J.I. et al. 2022. Palaeolithic archaeology in the conglomerate caves of north-eastern Iberia. Antiquity 96: 710–18. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2022.34

- RUIZ-REDONDO, A. In press. ‘Out of Franco-Cantabria’: the globalization of Pleistocene rock art, in O. Moro-Abadía, M. Conkey & J. McDonald (ed.) Deep-time

- art in the age of globalization: understanding rock art in the 21st century. London:Springer.

- SANCHIDRIÁN, J.L., A.M. MÁRQUEZ, H. VALLADAS & N. TISNERAT. 2001. Dates directes pour l’Art Rupestre de l’Andalousie. INORA 29: 15–19.

- TERLATO, G., H. BOCHERENS, M. ROMANDINI, N. NANNINI, K.A. HOBSON & M. PERESANI. Chronological and isotopic data support a revision for the timing of cave bear extinction in Mediterranean Europe. Historical Biology 31: 474–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2018. 1448395

- VILLAVERDE, V. 1994. Arte paleolítico de la Cova del Parpalló. Valencia: Servei d’investigació prehistòrica. – 2020. Avances en el estudio del Arte Rupestre Paleolítico del Mediterráneo Ibérico, in J.A. López & J.M. Segura (ed.) El Arte Rupestre del Arco Mediterráneo de la península Ibérica: 27–44. Alicante: DGCP.

- VILLAVERDE V. & A. CANTÓ. 2020. Les signes quadrangulaires dans la collection d’art mobilier de Parpalló, in E. Paillet, P. Paillet & E. Robert (ed.) Voyages dans une fôret de symboles: 295–302. Treignes: Cedarc.