In 2015, Merlin Burrows, a UK based company specializing in advanced satellite imaging, conducted scans to explore the enigmatic Labyrinth of Hawara in Egypt’s Faiyum region. Led by Tim Akers, a former specialist at RAF Menwith Hill with expertise in military satellite technology, these scans aimed to uncover the legendary underground complex described by the ancient historian Herodotus. Kept under strict non disclosure until 2025, the findings reveal a sprawling subterranean network, likely mapped using Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR). This article delves into the scans’ discoveries, the probable technology behind them, their alignment with prior research, and the speculative elements that fuel debate, offering a fresh perspective on Hawara’s ancient mysteries.

Merlin Burrows Scans: Mapping an Ancient Complex

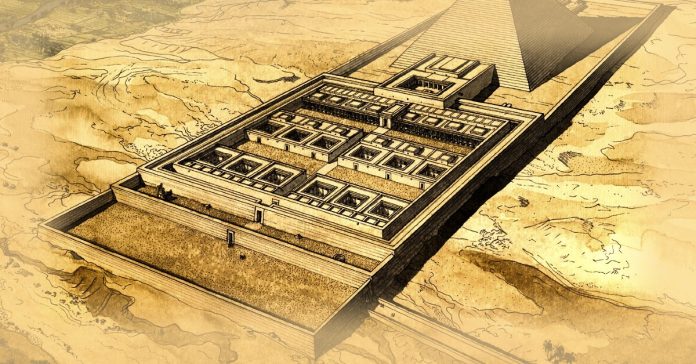

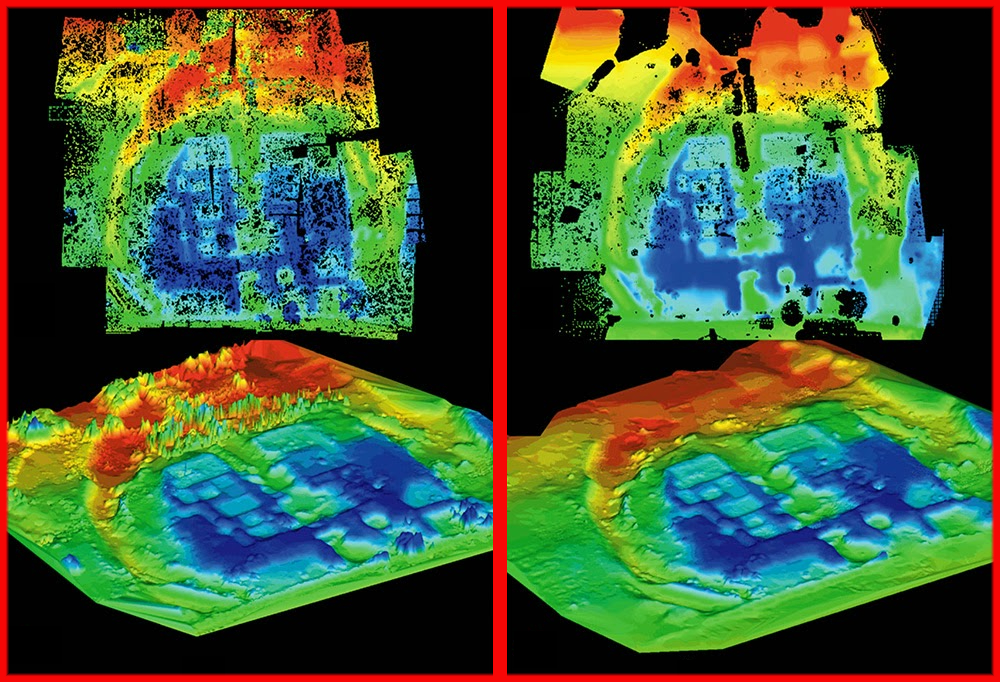

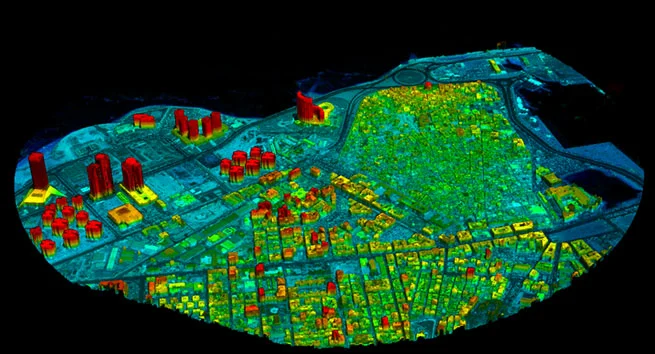

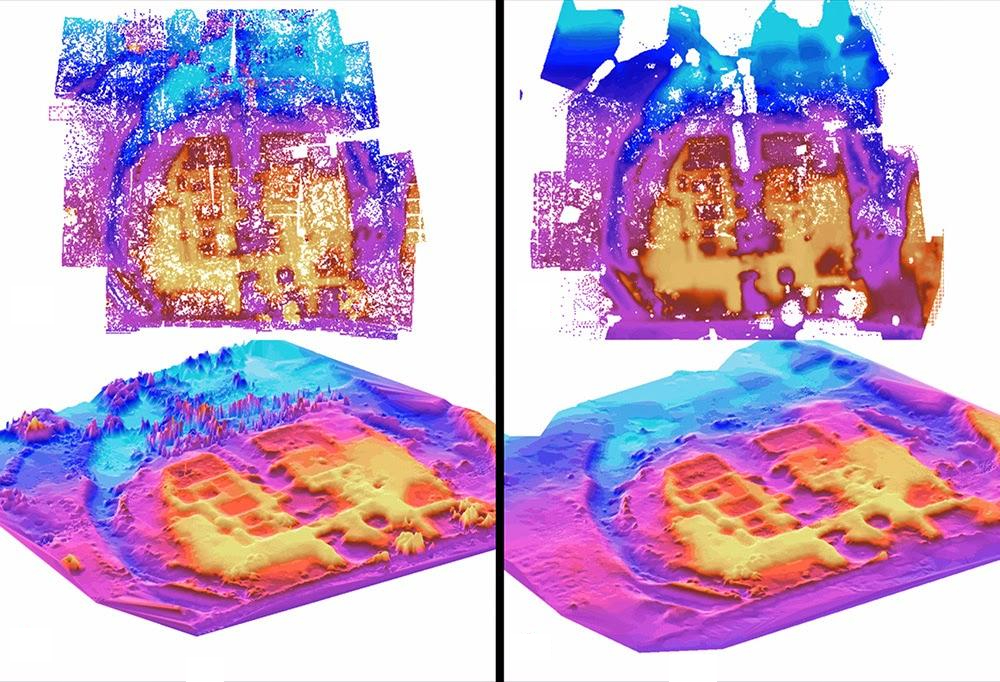

In 2015, Merlin Burrows deployed advanced satellite imaging, likely SAR, to probe Hawara’s subsurface. Akers’ military expertise enabled mapping of a complex spanning ten football fields. The scans reveal a central atrium (40 meters wide, 100 meters long) and four layers separated by 20 to 50 meters. A moat like structure, resembling the Egyptian Shen ring (according to Akers), suggests a sacred design. These findings build on earlier surveys, offering a glimpse into Hawara’s hidden depths, potentially supporting ancient accounts of a vast labyrinth.

The scans interpretively they claim also detect two chambers beneath the Hawara pyramid. One aligns with Flinders Petrie’s 1888 discovery; the other, beyond his “blind passage,” hints at a link to the labyrinth. This corroborates Herodotus’s description of a subterranean network with thousands of chambers. The proprietary SATSCAN© technology, though not fully disclosed, presumably may enhance SAR’s capabilities. This presumption is made, although not verified, because the scans reported depths far exceed known SAR technology. What the scans show are detailed visualization of subsurface features. Hypothetically through sophisticated radar data processing a hallmark of Akers’ military derived expertise.

Plausible Findings: Consistency with Prior Studies

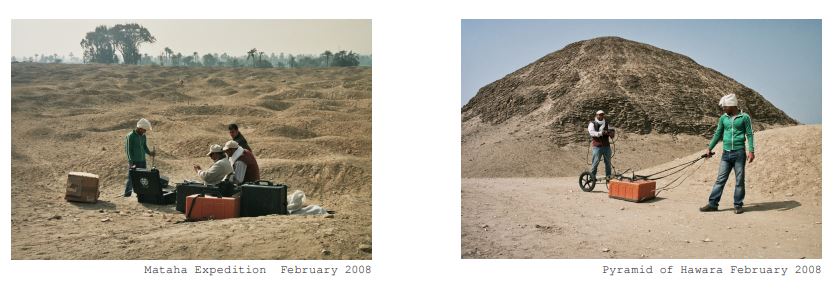

The Merlin Burrows scans align with earlier research, lending credibility to their shallow findings. The 2008 Mataha Expedition’s very low frequency electromagnetic (VLF EM) surveys detected thick walled rooms south of Amenemhet III’s pyramid, matching the scans’ atrium and layered structures. A 2023 SAR study confirmed shallow rectangular features (up to 0.5 meters deep), reinforcing the scans’ depiction of near surface anomalies. These consistencies suggest the scans accurately map Hawara’s upper subsurface, building on established geophysical evidence from multiple independent efforts.

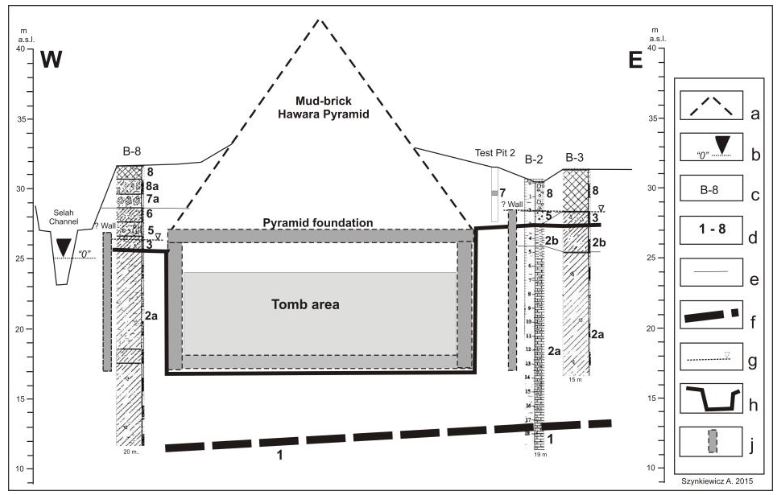

b) water level in the Selah canal. c) number of bore-hole. d) geological layers: 1 – Eocene limestone.

2a – Eocene mudstone. 2b – Eocene claystone 3 – mixed layers of calystone, anthropogenic overburden.

4 – Holocene river sand. 5 – sand and gravel, flood period. 6 – clay with rest of flora. 7 – limestone blocks.

7a – fragments of limestone. 8 – mixed layers, anthropogenic overburden. e) boundary of layer. f) top of Eocene limestone. g) ground water level. h) trench for the tomb cut in Eocene rocks. j) presumed wall

An Egyptian Polish mission’s findings, noting shallow groundwater (up to 8 meters), support the scans’ claim that deeper structures remain unaffected by water from the Bahr Wahbi canal. This aligns with Petrie’s 1888 measurements of a 277,000 square foot foundation, suggesting a large complex. The scans’ detection of Persian tomb shafts, likely from the Late Period, further supports historical accounts, making these elements a strong basis for future exploration of Hawara’s archaeological potential.

Exploring the Technology: Synthetic Aperture Radar

Merlin Burrows likely used SAR, a satellite based radar technology, for the 2015 Hawara scans. SAR emits microwave pulses to map surfaces and shallow subsurface features, penetrating a few centimeters to meters in dry conditions, such as Faiyum’s desert environment. Akers’ experience at RAF Menwith Hill, a hub for satellite intelligence, suggests possible access to advanced SAR systems. Potentially further enhanced by the proprietary SATSCAN© system. This could involve lower frequency bands (like L band, with a 23 cm wavelength) or data fusion techniques to improve resolution, as seen in other archaeological applications detecting paleochannels up to 2.84 meters deep.

SAR’s strength lies in its ability to produce high resolution images unaffected by weather or daylight. In dry, non conductive soils, L band SAR can penetrate a few meters, ideal for mapping shallow archaeological features. The Merlin Burrows scans’ detailed color coded layers (yellow, red, green, blue) indicate advanced processing, possibly combining multiple satellite passes to enhance depth visualization. Such techniques align with SAR’s use in other Egyptian sites, where buried foundations were detected in the Western Desert.

SAR’s Limitations: A Scientific Reality Check

Despite its capabilities, SAR faces significant constraints, particularly in penetration depth. Scientific studies confirm that X band SAR (3 cm wavelength) penetrates less than a meter in rock or moist soil, while L band reaches only a few meters in dry sand. Akers claims of imaging structures at 100 meters, as reported for the Burrows scans, exceed these limits. Even SAR Doppler Tomography, which infers shallow features from surface vibrations, cannot reliably extrapolate to tens or hundreds of meters, as vibration signals weaken and scatter in dense rock.

Ground based methods, like seismic tomography or ground penetrating radar (GPR), are required for deeper imaging. Seismic tomography uses low frequency sound waves to probe hundreds of meters. GPR however can reach tens of meters in dry conditions. In contrast, SAR’s microwave based approach remains surface focused. This makes the Merlin Burrows scans’ deeper claims scientifically questionable. Without physical validation through excavation or complementary technologies we cannot validate the 100m claims.

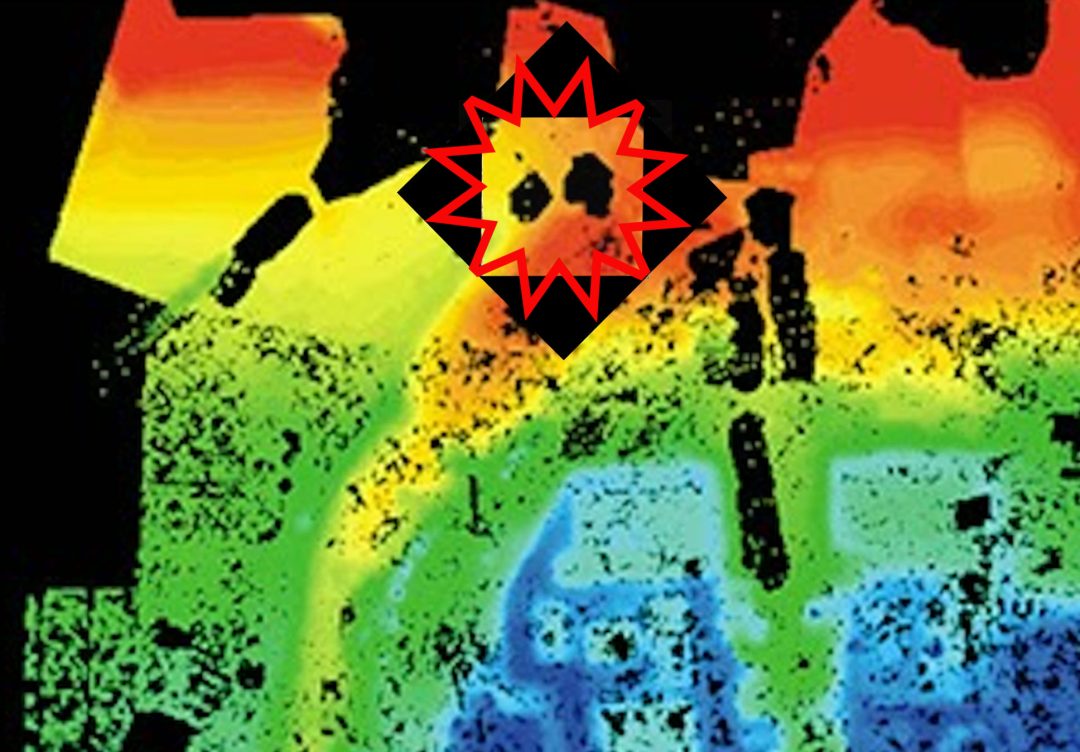

Speculative Claims: Pushing Beyond Evidence

Some Merlin Burrows scan interpretations venture into speculative territory. The scans purportedly identify a 40 meter long object, dubbed “Dippy,” described as metallic and possibly a technological artifact or interdimensional portal (citation needed). Such interpretations lack physical evidence and strain the team behind the Burrows scans credibility. SAR’s shallow penetration cannot reliably image structures at 20 to 100 meters, as claimed for the scans’ layered features. These assertions resemble over-extrapolated claims using SAR Doppler Tomography made by Corrado Malanga and Filippo Biondi.

The so called “Dippy” object, requires ground based validation to move beyond conjecture. The scans’ deeper layers, spanning 20 to 100 meters, rely on unverified processing methods. Possibly involving speculative extrapolation of surface data. Without excavations or seismic surveys, these claims remain unsupported. This echoes the skepticism surrounding other unverified deep imaging assertions in Egyptian archaeology.

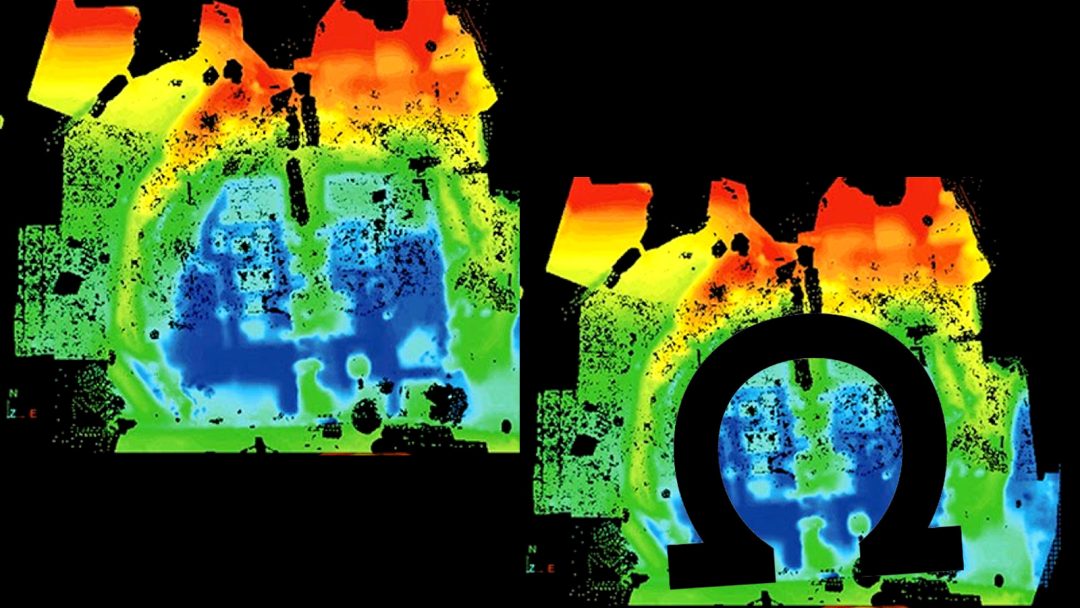

The Omega Moat: A Symbolic Boundary

The Merlin Burrows scans claim to reveal a moat like structure encircling the Hawara site. They’ve dubbed it the “omega moat” for its resemblance to the Greek omega. Or, Egyptian Shen ring, symbols of eternal life. Detected closer to the surface, this feature, they claim, suggests a ritual or defensive boundary, akin to the dry moat at Saqqara. Its shallow depth aligns with SAR’s penetration limits (centimeters to meters), making it a plausible finding. Unlike the speculative “Dippy” object, the moat’s symbolic design supports historical accounts of Hawara’s sacred significance, warranting further investigation.

Challenges to Archaeological Acceptance

Mainstream archaeology has not embraced the 2015 Merlin Burrows scans, perhaps due to their secrecy until 2025. Fear of backlash from Egyptian authorities, like Dr. Zahi Hawass, led to them withholding the scans according to Louis De Cordier. Groundwater and bureaucratic hurdles, stall physical verification. SAR’s inability to image beyond a few meters necessitates ground based technologies for deeper exploration. The scans’ plausible shallow findings hold promise, but their deeper claims await rigorous digs to reshape our understanding of Hawara.

The Bahr Wahbi canal, constructed in the 1830s, exacerbates exploration challenges by raising groundwater levels, flooding parts of the Hawara pyramid’s entrance. This environmental obstacle, noted in earlier studies, limits access to deeper structures, leaving the scans’ claims untested. The archaeological community’s skepticism reflects the need for physical evidence to validate such ambitious findings.

A Path Forward for Hawara’s Mysteries

The 2015 Merlin Burrows scans offer a compelling view of Hawara’s labyrinth, blending plausible shallow discoveries with speculative deeper claims. Their alignment with earlier surveys, like the Mataha Expedition and 2023 SAR studies, suggests a real complex. But, claims of 100 meter depths and mysterious objects like “Dippy” exceed SAR’s scientific limits. Ground based methods, like seismic tomography or GPR, are essential to verify these findings. As the archaeological community awaits excavation, the scans remain a provocative chapter in Faiyum’s ancient story. Further exploration, is required, to solve this enduring mystery.

The scans’ legacy lies in their potential to inspire new research. By combining advanced technology with historical accounts, they highlight Hawara’s significance as a site of ancient engineering. Future excavations, guided by the scans’ plausible elements, could unlock the labyrinth’s secrets, revealing whether it matches Herodotus’s awe inspiring vision or holds even greater surprises beneath the sands.