On June 15th, 1837, a solitary figure stood before Menkaure’s pyramid at Giza. With its weathered red granite base shimmering beneath Egypt’s unforgiving sun. Colonel Richard William Howard Vyse, had left behind a soldier’s routine to pursue the mysteries of the ancient world. Deep within that pyramid’s stone heart, he uncovered the lost sarcophagus of Menkaure, a basalt coffin fashioned 4500 years ago for the pharaoh of Egypt’s Fourth Dynasty. By October 1838, that same relic vanished into the Mediterranean Sea aboard the Beatrice. A brigantine schooner, which was overtaken by a relentless storm. To this day, it resides on the seabed. A testament to Ancient Egypt’s dynastic empire. Still unrecovered after 186 years.

Richard Vyse: 19th Century Adventurer

Vyse was born on July 25, 1784, in the quiet village of Stoke Poges, Buckinghamshire. Born to a lineage defined by military service, his father, General Richard Vyse, had commanded battalions during the American Revolutionary War. His mother, Anne Howard, inherited wealth and prestige as the daughter of Field Marshal Sir George Howard. Whose victories in the Seven Years’ War adorned family lore. Richard spent his youth at Stoke Place, a sprawling Georgian manor. Where oak paneling framed the halls and expansive meadows stretched beyond leaded windows. Mornings brought lessons in Latin and mathematics, evenings tales of battlefield triumphs from his father’s lips, shaping a boy both disciplined and curious.

At sixteen, in 1800, Vyse joined the 1st Dragoons as a cornet, a junior officer astride a chestnut mare, saber at his side. Promotions arrived briskly: lieutenant in the 15th Light Dragoons by 1801, captain by 1802, major by 1813. He rode through the Napoleonic Wars, mud caking his boots at Salamanca in 1812, cannon smoke stinging his eyes. Standing six feet tall, lean from years in the saddle, his gray eyes betrayed a mind restless for more. From 1807 to 1818, he sat in Parliament, representing Beverley and Honiton, debating tariffs in smoky chambers. A role that dulled his spirit. By 1835, at fifty one, he sought purpose beyond Westminster’s walls, drawn to Egypt by Napoleon’s 1798 campaign and Europe’s craze for pharaonic relics.

Vyse Travels to Egypt

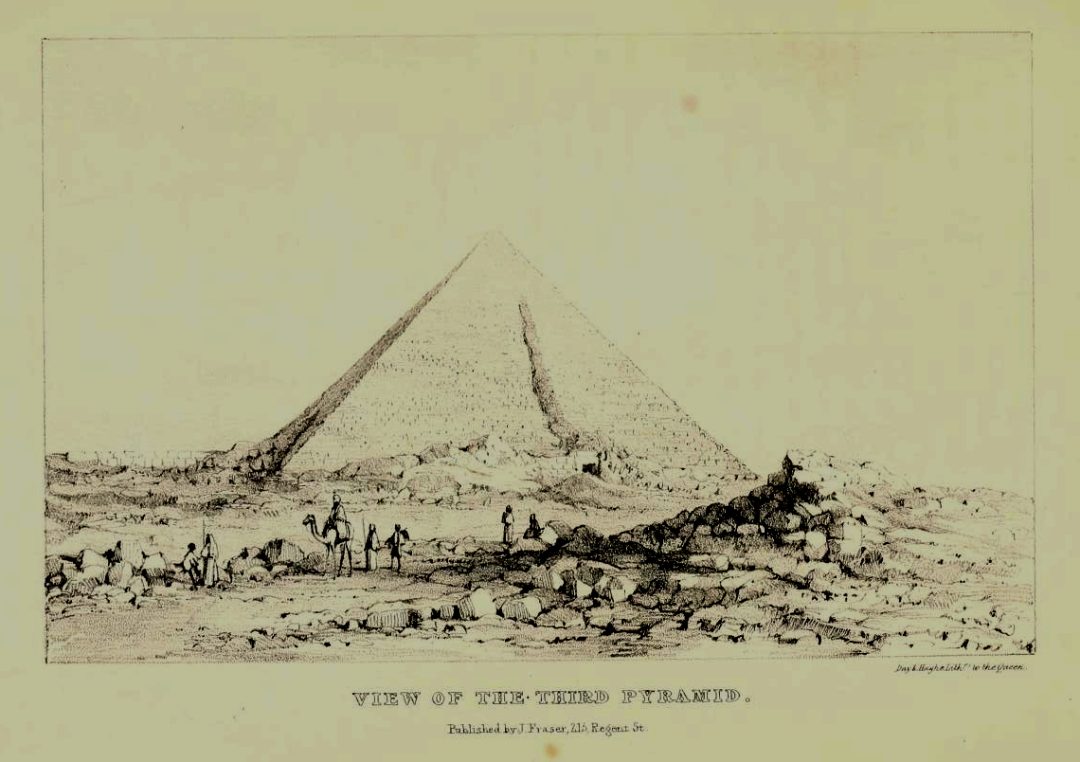

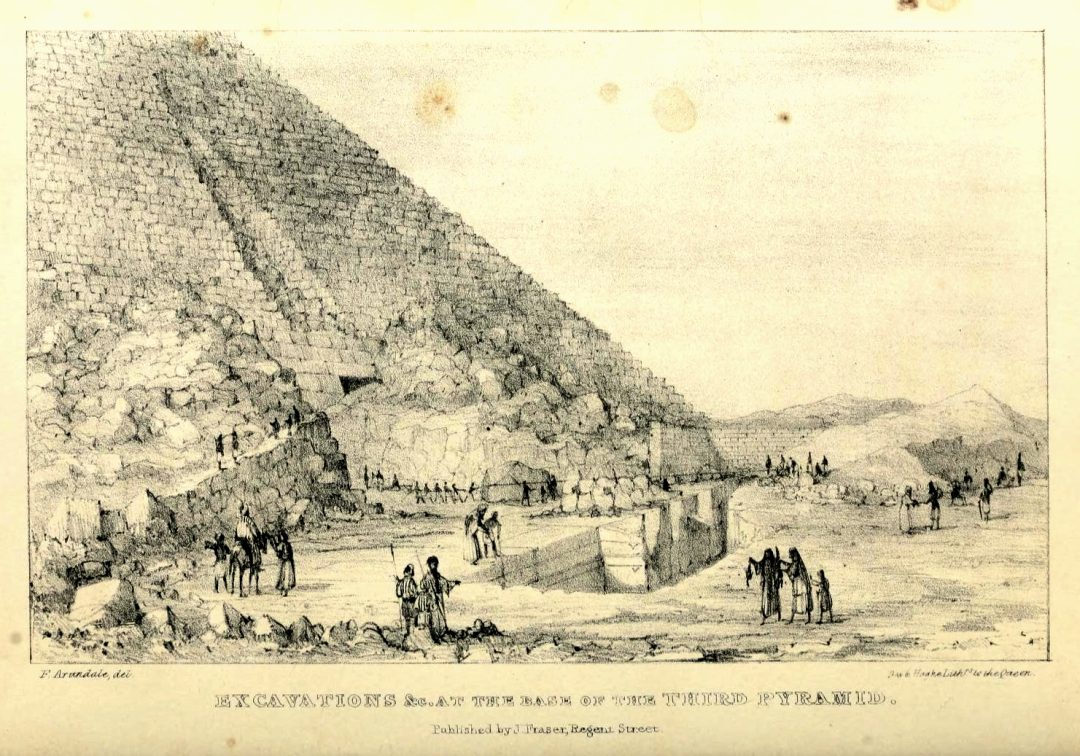

Driven by his dreams, Vyse reached Alexandria in January 1837, on a steamer cutting through the Nile’s brown waters. As they sailed, Menkaure’s pyramid rose before him. Seventy feet high, its base clad in red granite quarried from Aswan. Its limestone crown worn by 4500 years of wind and sun. He lived in a canvas tent near its base, waking to coffee brewed over a fire, poring over maps by lamplight. In his memoir, Operations Carried on at the Pyramids of Gizeh in 1837, published in 1840 he recorded his adventure. Carrying out excavations with explosives, in what later came to be referred to as “Dynomite archeology”.

Discovery of a Lifetime

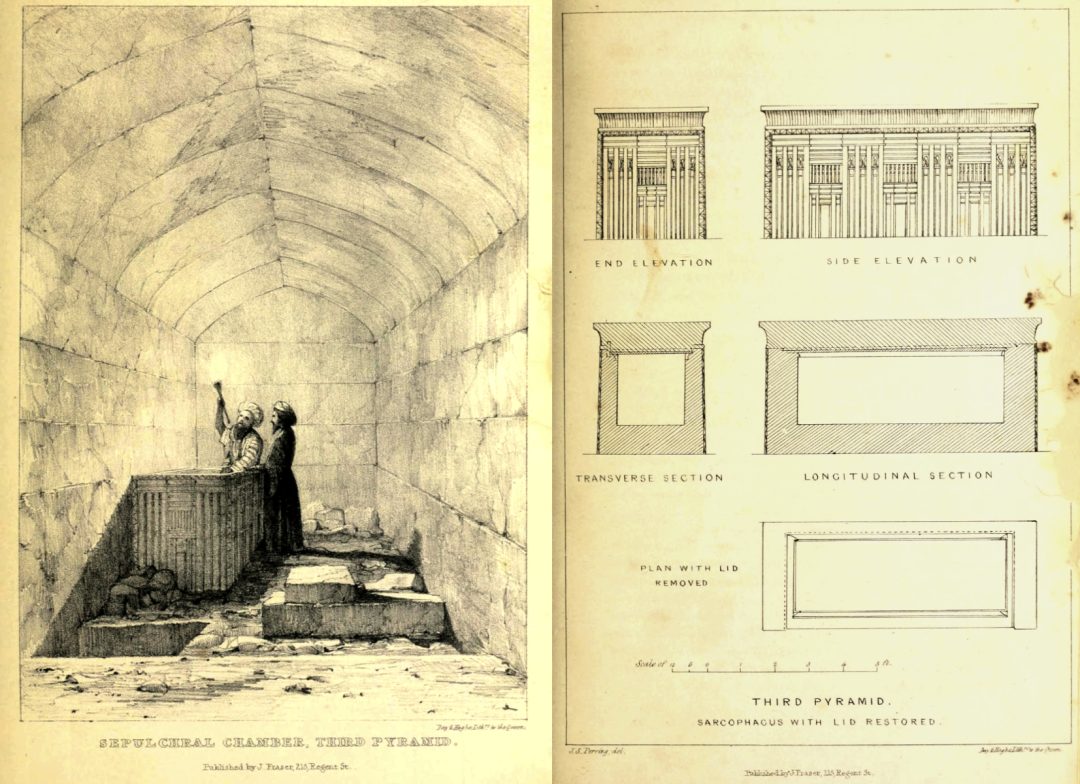

On June 15th, he detonated charges, stone dust clouding the air, until he breached a burial chamber. There amongst the ruins sat a sarcophagus: 8 feet long, 3 feet wide, 2 feet deep. Vyse stood before the sarcophagus of Menkaure, its basalt form a silent relic of a lost age. Over the following weeks, his team meticulously extracted it. Using wooden levers and ropes to maneuver the nearly 1000-pound coffin through the pyramid’s narrow passages.

A task completed by early July. Wrapped in canvas and hauled by camel caravan to Alexandria. It arrived at the bustling port by late August 1838, where Vyse arranged its transfer to England for study. On September 10th, it was loaded onto the Beatrice, a brigantine schooner. The ship was moored amidst the clamor of merchants and dockhands, secured in the hold with hemp ropes alongside crates of granite and gold. Setting the stage for its ill-fated voyage

Who was Menkaure?

Menkaure was pharaoh of Egypt, during the fourth Dynasty, between 2532 and 2503 BCE. He was the son of Khafre & grandson of Khufu. He ruled a land tethered to the Nile’s cycles; its people clustered in mud brick homes along its banks. They included farmers coaxing barley from silt with wooden plows, while metallurgists honed their craft. Stone masons busily crafted the blocks for the temples and sarcophagi, like his, for the elite. Memphis, the sprawling capital, was five miles from Giza, scribes there documented everything from the mundane to the divine. While priests in temples chanted to Amun & street merchants hawked their wares.

His pyramid, Vyse breached, demanded decades of labor. Workers felled granite from Aswan’s cliffs, 500 miles south, each block weighing apx. 50 tons. They dragged them across desert sands on sledges of acacia wood, pulled by teams of oxen and men. Then they were floated downriver on reed barges. Limestone for the pyramid came from Tura, 10 miles east, quarried with flint picks, its white slabs hauled to cap the structure. Rising 70 feet, smaller than Khufu’s 481, it puzzled scholars: some saw dwindling wealth, others a turn toward humility. Menkaure’s legacy endures in finely carved slate statues. Depicting him with deities such as Hathor, their almond-shaped eyes etched with precision, now housed in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum.

A Sarcophagi for a Pharoah

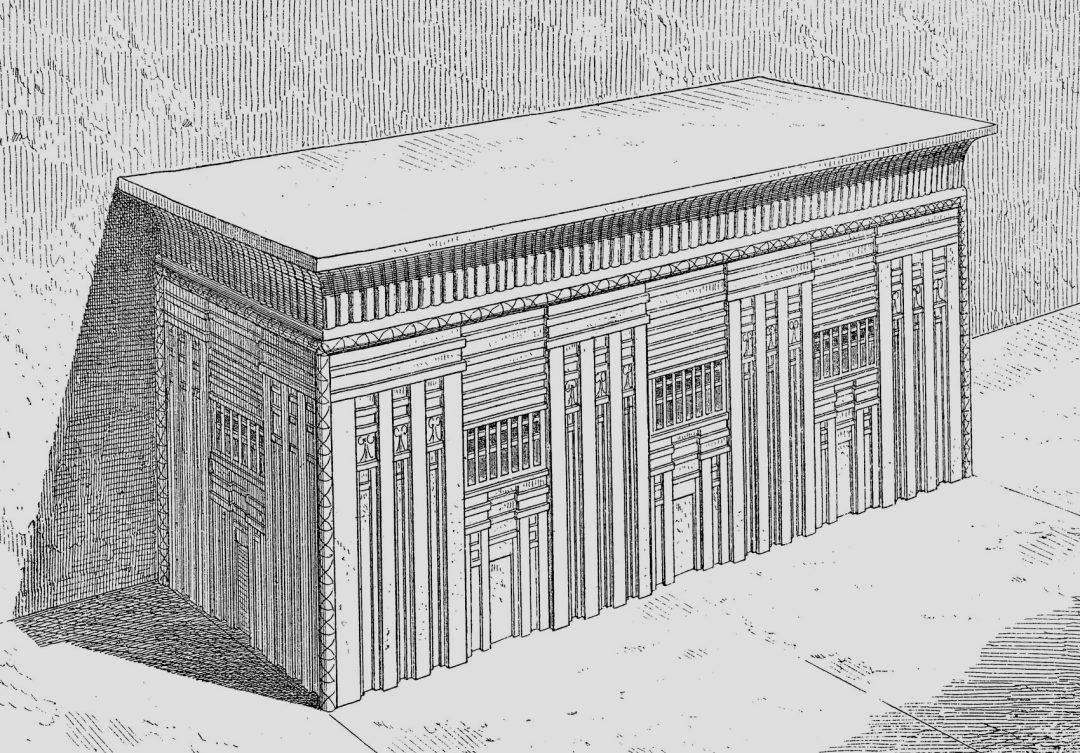

The sarcophagus emerged from basalt deposits near Fayum, 50 miles southwest of Giza, where volcanic rock hardened millennia before. Laborers shaped it with flint chisels and stone hammers, smoothing its gray black surface to a sheen by lapping and polishing with corundum. Weighing nearly 1000 pounds, it bore no glyphs or reliefs, only geometric panels on its sides; by Vyse’s documented account. Its simplicity a hallmark of the Old Kingdom’s stark reverence. One can picture priests prepared Menkaure’s body, organs removed, flesh dried with natron, wrapped in linen strips, anointed with myrrh. Once placed inside, the lid was sealed with resin. Prior to 1837, upon Vyse’s arrival looters, in antiquity, had stripped the tomb bare, leaving an empty room 4500 years old, a hollow shell once reserved for a pharaoh’s bid of immortality.

The Sarcophagi’s Ill-Fated Voyage

Move to September 1838, where Alexandria’s port thronged with life. Merchants weighed saffron on brass scales, dockhands rolled barrels of olive oil, and the Beatrice rested at her moorings. A brigantine schooner, she stretched 100 feet from bow to stern, her hull built from English oak felled in Kent’s forests, seasoned for two years before assembly. Shipwrights in Liverpool’s yards, circa 1821, framed her keel with iron bolts, clad her planks in copper sheathing to ward off worms, and raised two masts: one square rigged with three sails, one fore and aft with a gaff rig. Brigantines ruled Mediterranean trade, their 400 ton holds ferrying goods (wine from Sicily, cotton from Izmir) across a sea linking three continents. Neither rare nor luxurious, they outnumbered grand frigates ten to one, their crews smaller, their upkeep cheaper.

A Captain Goes Down with his Ship

Captain Richard Mayle Whichelo, fifty-two, owned a share of her. Born in 1786 in Portsmouth, he joined the Royal Navy at nineteen. Serving on HMS Neptune at Trafalgar in 1805, where cannon fire deafened his left ear. By 1838. His crew, twenty men strong, blended British deckhands and Maltese riggers. On September 10th, Vyse’s team arrived, hauling the sarcophagus on a cart drawn by six mules, its basalt bulk swaying. They hoisted it aboard with a block and tackle, securing it in the hold with hemp ropes, alongside 200 crates of granite blocks and gold coins bearing Ptolemy’s profile.

On September 20th, the Beatrice sailed from Alexandria, her sails billowing in a 10 knot southerly breeze, her course northwest toward Malta. Whichelo stood at the helm, plotting a 700 mile leg. She docked in Valletta’s Grand Harbour on October 13th. Her crew unloading empty casks, taking on 50 barrels of water, 20 sacks of biscuit, and 10 gallons of rum. Three days later, October 16th, she departed, threading through fishing boats, her bow cutting a sea that shimmered under a waning moon.

Lost at Sea

The Beatrice vanished in late October 1838; her fate pieced from fragments. Lloyd’s Loss and Casualty Book, a leather-bound tome of shipping losses, records: “Beatrice, Whichelo, sailed from Alexandria 20th September and from Malta 13th October for Liverpool, and has not since been heard of.” No captain’s log survived, or wreckage washed ashore.

The western Mediterranean, 2400 miles from Gibraltar to Crete, drops to 5000 feet in its basins but rises to 150 feet near coasts. Spanish logs from Cartagena and Alicante, preserved in municipal archives, detail October 1838 storms: winds gusting to 40 knots, waves cresting at 15 feet, rain slashing visibility to 100 yards.

Whichelo could have encountered this maelstrom, approximately 200 miles west of Malta, between Sardinia and Spain. Esteban Llagostera Cuenca, a Spanish historian, argued in a 2003 study that she rests a mile off Cartagena, where currents flow at 1 knot. Gibraltar, 600 miles west, offers another possible location, its straits a graveyard for ships.

Vyse received word by January 1839, relayed by Alexandria agents via steamer to London, confirmed in Lloyd’s reports. His memoirs mourn the loss, a bitter footnote to his triumph.

2008: A Quest Begins

In 2008, the lost sarcophagus of Menkaure kindled a modern pursuit. Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, steered by Zahi Hawass, joined Spain’s National Geographic Institute and Trion Technology, a Valencia firm specializing in underwater salvage. Javier Noriega, a Spanish marine expert, directed the operation. Born in 1970 in Madrid, Noriega studied at Complutense University, diving Roman wrecks off Alicante. Robert Ballard, who pinpointed the Titanic in 1985, joined the pursuit consulting from Woods Hole, his voice crackling over satellite calls.

The Search

The search zeroed on a 30 square mile patch off Cartagena, mapped from Vyse’s memoirs, Lloyd’s logs, and 1838 routes. From April 15th to June 30th, the team aboard the Mar Esperanza, a 120 foot steel research vessel. It faced shifting seas: early weeks brought 1-foot ripples under 5 knot breezes, late May saw 5-foot swells and 20 knot gusts whipping whitecaps. Noriega deployed a Kongsberg EM 3002 multibeam sonar, towed at 100 feet on a 300-foot cable, its pings charting the seabed in grids. Two Remotely Operated Vehicles, each 6 feet long with 1080p cameras and claw arms, descended to 150 and 400 feet. Their lights slicing through silt, feeds streaming to a control room lined with monitors.

Divers in drysuits, five men from Trion, dove three times (May 3, May 18th, June 12th) each descent a 90-minute plunge to 200 feet, 1.5 knot currents tugging at their 50-pound oxygen tanks. They searched by hand, gloved fingers sifting sand, visibility 20 feet in murky green. Sonar flagged anomalies: a 50-foot wreck at 180 feet, a Byzantine trader with amphorae; a 30-foot hulk at 320 feet, a 17th century galley with rusted cannon. The Beatrice eluded them. Hawass’s May 12th statement in Al Ahram claimed progress; Noriega’s logs, later in Revista Arqueología Subacuática, noted a 100-foot shadow at 320 feet, unconfirmed by ROVs. But Egypt’s 2011 unrest severed funding. The Sarcophagi left in its watery grave. Noriega, in a 2010 interview with El País, vowed to return: “It’s there, waiting.”

A Legacy Woven Through Ages

The lost sarcophagus of Menkaure is a tale century’s old. Born in 2500 BCE for a pharaoh’s rest, unearthed in 1837 by Vyse’s will, lost in 1838 to the Beatrice’s doom. It lingers still, 186 years submerged, 4700 years from its crafting. Vyse’s memoirs, penned in his Buckinghamshire estate, it’s last documented memory. Whichelo’s schooner, carried it to ruin, his crew’s cries lost to wind. Noriega’s 2008 hunt haunted its trail. In 2025, it rests a mile off Cartagena or deeper, claimed by Britain, Egypt, and Spain, it’s worth beyond measure. Beneath the Mediterranean, it endures, a pharaoh’s final resting place, in a mariner’s grave. A challenge for the ages; left for someone to pick up the torch.

For More mysteries of Ancient Egypt read The Ankh: Symbol of Life and Spiritual Power in Ancient Egypt