Forged From Fire

In southeastern Turkey, a lost civilization rises from the depths of time, its legacy etched in megaliths and forged in metallurgy. Göbekli Tepe’s T-shaped pillars rise from a limestone ridge, dating to 9600 BCE; Nevalı Çori’s sunken ruins echo from beneath the Euphrates. Farther north, Norşun Tepe’s mound, partially drowned by Lake Keban, revealed layers of copper and bronze work from 4000 BCE onward. Now at Gre Fılla copper artifacts glint in the Upper Tigris Valley.

These sites, spanning Upper Mesopotamia, reveal a society of staggering complexity, predating pottery and cities. Recent discoveries, including copper smelting at Gre Fılla around 8000 BCE, unveil a people who mastered stone and metal with audacious skill. This article explores their world, a tapestry of monumental architecture and technological prowess, challenging everything we thought about humanity’s ancient past.

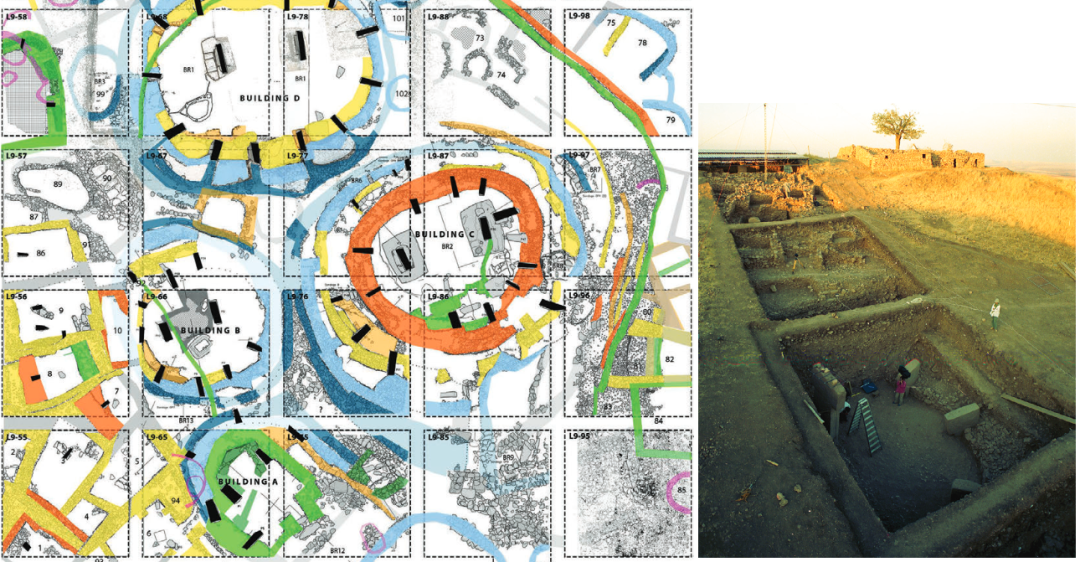

Göbekli Tepe: A Settlement Unveiled

Göbekli Tepe astonishes with its T-shaped pillars, erected between 9600 and 7000 BCE. Archaeologists once labeled it a temple, a ceremonial hub for nomads. Excavations since 2019, led by Dr. Lee Clare and the German Archaeological Institute, reveal a different truth. Stone-founded houses, cisterns capturing rainwater, and thousands of grinding stones for wild grains dot the site. People lived here, cooked here, slept here; they built a settlement, not a fleeting shrine. This lost civilization thrived before agriculture dominated, its daily life unfolding amid megaliths that still stand, weathered but defiant, after 11,000 years.

A Shift in Perspective

The discovery shatters old assumptions. Permanent dwellings at Göbekli Tepe, predating widespread farming by centuries, suggest social cohesion drove stability. Families gathered, worked, and gazed upon their towering creations, each pillar a testament to collective effort. This wasn’t a transient camp; it was a foundation, a cornerstone of a lost civilization that pulsed with ingenuity long before Sumer’s ziggurats rose in 3000 BCE.

Nevalı Çori: A Legacy Submerged

Life Before the Flood

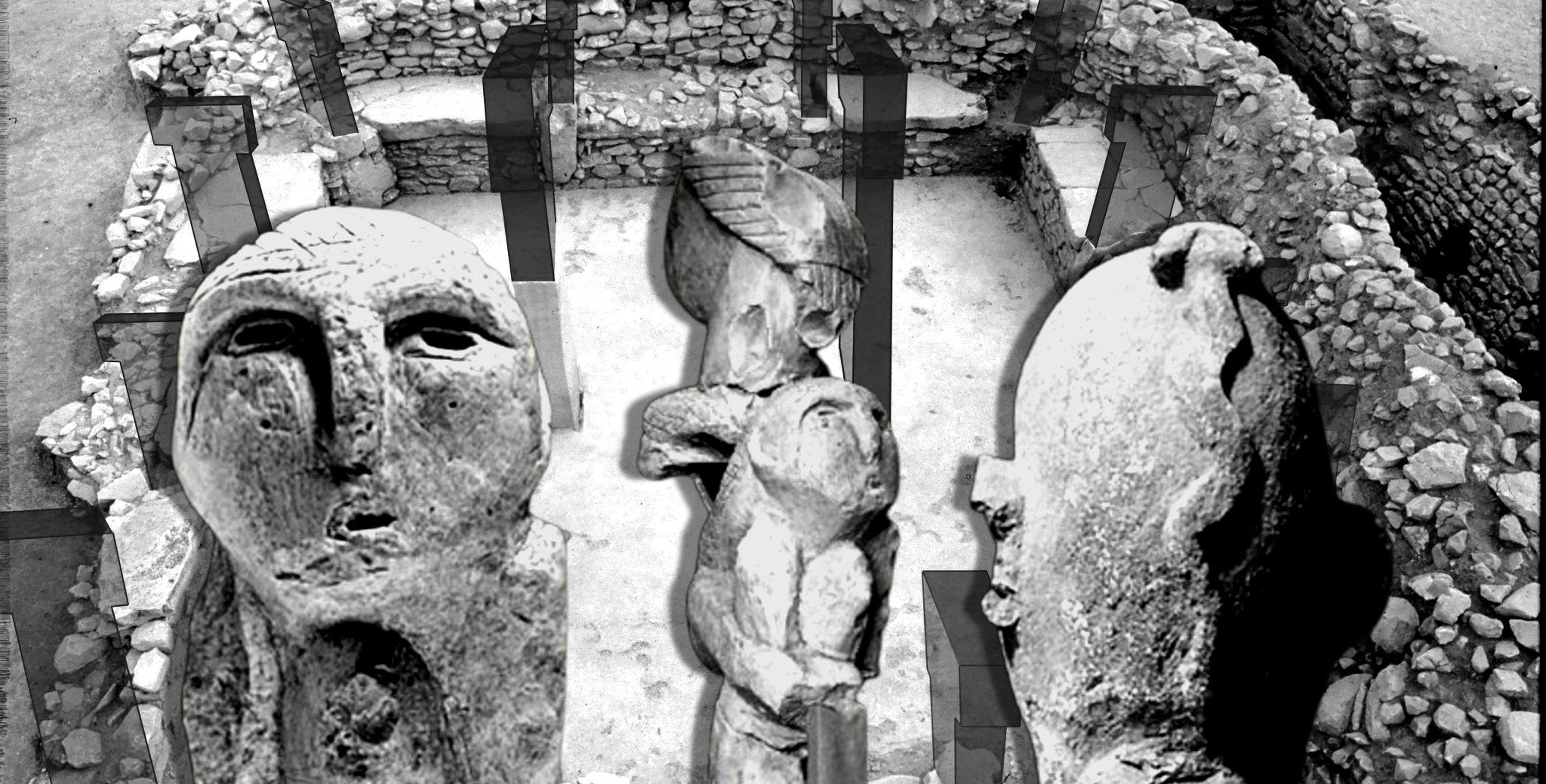

Forty miles from Göbekli Tepe, Nevalı Çori flourished between 8400 and 8000 BCE. Harald Hauptmann excavated it in the 1980s, uncovering rectangular houses with thick stone walls and underfloor channels, possibly for drainage or warmth. T-shaped pillars, mirroring Göbekli Tepe’s, anchored the site; limestone statues, a bald head with a snake tuft and a bird, showcased their artistry. The oldest domesticated einkorn wheat appeared here, a glint of agriculture’s birth. This lost civilization settled, innovated, and revered its megaliths until the Euphrates claimed it in 1992, submerged beneath the Atatürk Dam.

Nevalı Çori Copper

A 2014 study by Paul Ambert, referenced in the 2025 Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, adds to Nevalı Çori’s legacy. During the Early Bronze Age (EBA-1, circa 3000 BCE), its inhabitants smelted copper, a skill that hints at a remarkable continuity. Though submerged beneath the Euphrates since 1992, this site links the lost civilization’s early ingenuity to a broader metallurgical evolution.

Norşun Tepe: A Metallurgical Stronghold

Layers of Metal and Time

Norşun Tepe, in Elazığ Province, emerges as a vital node in this ancient network. Excavated between 1968 and 1974 by Harald Hauptmann, this tell spans the Chalcolithic (5000 BCE) to the Iron Age (600 BCE). Partially submerged by Lake Keban since the dam’s completion, its 35-meter-high acropolis and sprawling terraces (800 by 600 meters) reveal 40 occupation layers. Late Chalcolithic levels yield copper and arsenical bronze production, dated to 4000 BCE; Early Bronze Age phases show continued metalwork, paralleling Nevalı Çori’s later efforts. This lost civilization harnessed metallurgy here, its furnaces glowing amid a shifting landscape.

A Bridge to the Bronze Age

Norşun Tepe’s significance deepens the narrative. Its arsenical bronze, deliberately alloyed with arsenic-bearing materials, marks a leap in sophistication before 4000 BCE. The site’s Early Bronze Age copper production aligns with Nevalı Çori’s, suggesting a regional tradition that endured floods and time. Though less famed than Göbekli Tepe’s megaliths, Norşun Tepe’s metalwork anchors this lost civilization’s technological reach, its submerged ruins a silent witness to their craft.

Gre Fılla: Metallurgy’s Early Flame

Copper Forged in Fire

In the Upper Tigris Valley, Gre Fılla ignites the narrative with copper smelting around 8000 BCE. Üftade Muşkara’s team unearthed a bar-shaped copper object and vitrified soil, analyzed with X-ray diffraction and scanning electron microscopy. Chromite grains and copper droplets, fused at over 1,000°C, reveal deliberate ore processing; lead isotopes trace the metal to Trabzon, 300 kilometers north. This lost civilization didn’t stumble into metallurgy; they pursued it, trading across vast distances, mastering fire and stone in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB).

A Craft Beyond Its Time

The skill astonishes. Smelting predates the Chalcolithic (5000 BCE) by millennia, rivaling cold-worked copper at Çayönü (7000 BCE). Gre Fılla’s artisans controlled high temperatures, shaped metal with precision; their work hints at specialization, a hallmark of complexity. This lost civilization, stretching from Göbekli Tepe to the Tigris, wielded technology that defies its ancient label, its copper artifacts glinting like stars in a forgotten sky.

The T-Pillar Connection

T-shaped pillars unite these sites across the Taş Tepeler region: Göbekli Tepe, Nevalı Çori, Karahan Tepe, Sefer Tepe. Carved with foxes, snakes, and human hands, they tower up to 18 feet, quarried from local limestone, hauled by sheer will. They frame enclosures, line walls; their consistency signals a shared culture, a lost civilization bound by belief. Gre Fılla, though lacking pillars in current records, aligns with this PPNB world, its metallurgy a parallel triumph. Nevalı Çori’s EBA-1 copper ties it further, a thread from 8000 BCE to 3000 BCE.

A Civilization Redefined

Megaliths Before Fields

Traditional timelines place settlements after agriculture, complexity after cities. Göbekli Tepe upends this, thriving before farming took hold. Nevalı Çori’s wheat followed, a gradual shift; Gre Fılla’s copper predates both, a technological leap at 8000 BCE. This lost civilization built first, bonded through megaliths, then innovated. Hundreds collaborated, as Klaus Schmidt estimated for Göbekli Tepe; builders, carvers, metalworkers sustained a network reaching the Black Sea. Not urban, but intricate, they rivaled Sumer (3000 BCE) in ambition, if not scale.

Metallurgy as Catalyst

The Journal report frames Gre Fılla’s metallurgy as part of a cognitive surge, not an anomaly. Nevalı Çori’s later smelting (3000 BCE) extends this arc, a tradition rooted in PPNB fire. Copper tools or ornaments likely honed their hunts, enriched their rites; social unity, forged amid T-pillars, spurred these advances. Agriculture emerged later, a byproduct of a lost civilization already adept at reshaping its world, its megaliths and metallurgy standing as twin pillars of progress.

A Tapestry Across Time

Nevalı Çori’s submersion in 1992 obscures its depths, yet Gre Fılla’s copper and Göbekli Tepe’s homes illuminate the past. From Şanlıurfa’s ridges to the Tigris Valley, this lost civilization spanned Upper Mesopotamia, trading obsidian and copper, erecting megaliths that endure. Nevalı Çori’s metallurgy, noted alongside sites like Norşun Tepe, binds it to Gre Fılla’s earlier flame. They didn’t drift through history; they sculpted it, their stone and metal a legacy echoing from 9600 BCE to 3000 BCE. Each dig uncovers more, a testament to this lost civilization.

Stay tuned to Ancient History X for further tales from antiquity’s edge.