The religious and cultural milieu of ancient Mesopotamia profoundly shaped the theological and ethical foundations of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. While these Abrahamic faiths emerged as distinct monotheistic traditions, their core narratives, legal frameworks, and cosmological ideas bear the indelible influence of Mesopotamian thought. This article examines the transmission and adaptation of Mesopotamian motifs into Abrahamic theology, focusing on textual parallels, sociopolitical contexts, and the hermeneutical processes through which polytheistic myths were reimagined within monotheistic paradigms.

Mythological Syncretism: Flood and Creation Narratives

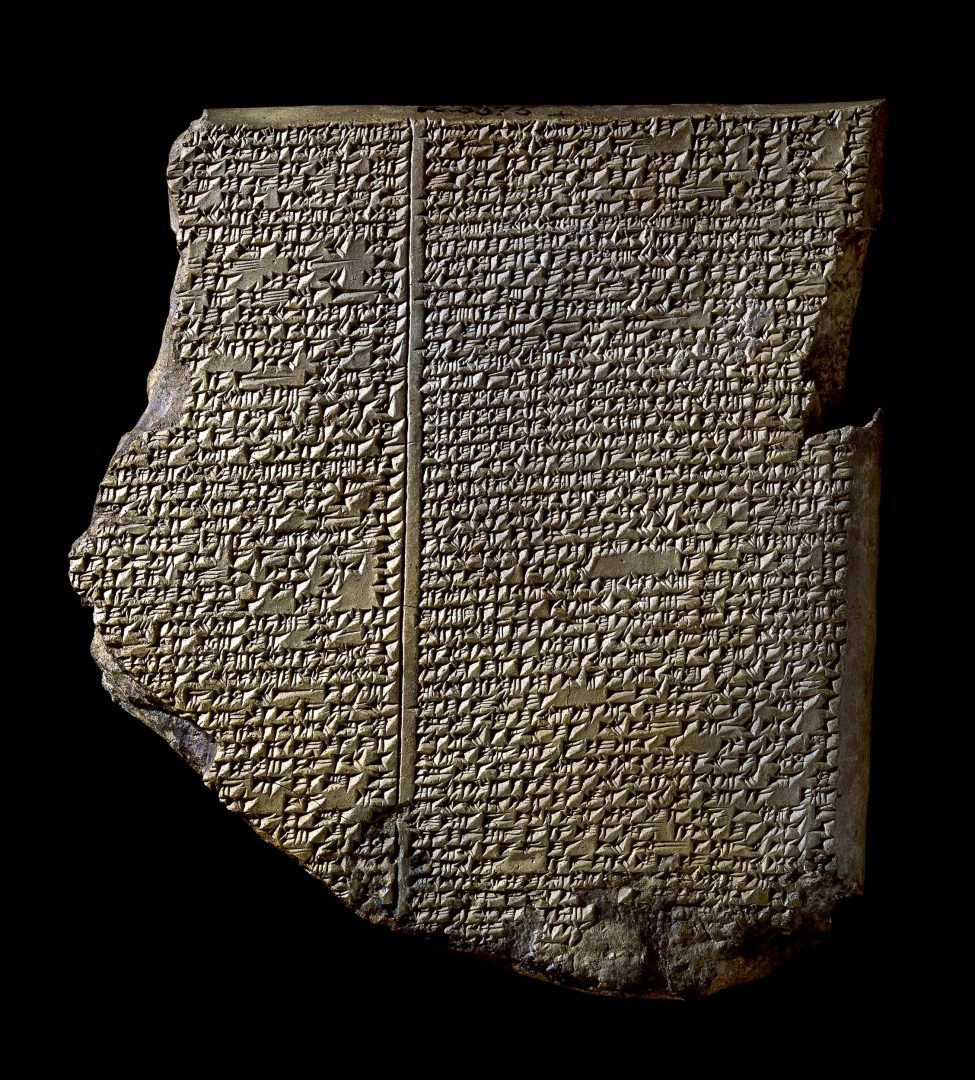

The Genesis flood account (Genesis 6–9) and the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh (Tablet XI) share striking structural and thematic parallels, including divine wrath, a deluge, and the preservation of life through a divinely instructed vessel.¹ Similarly, the Enuma Elish, Babylon’s creation epic, depicts cosmic order arising from primordial chaos through divine conflict—a motif reinterpreted in Genesis 1–2, where a single God creates ex nihilo without struggle.² These parallels suggest not mere borrowing but a deliberate reworking of Mesopotamian tropes to assert theological distinctiveness. For instance, the Genesis flood narrative omits the capricious polytheism of Mesopotamian myths, instead emphasizing Yahweh’s moral governance and covenantal fidelity.³

Legal Traditions: From Hammurabi to Moses

The Code of Hammurabi (c. 1754 BCE) and Mosaic Law (Exodus 20–23) both employ the lex talionis (“eye for an eye”) and prioritize social order through retributive justice.⁴ However, the Torah reframes these laws as divine revelation rather than royal edict, embedding them within a covenant theology that binds Israel to Yahweh.⁵ This shift mirrors the structure of Mesopotamian suzerainty treaties, where vassal obligations were enforced through blessings and curses—a template evident in Deuteronomy 28.⁶ The Abrahamic faiths thus appropriated Mesopotamian legal formalism but subordinated it to a transcendent moral authority.

Theological Reconfigurations: Divine Sovereignty and Eschatology

Mesopotamian conceptions of divine kingship, wherein gods like Marduk ruled the cosmos, resonate in Yahweh’s portrayal as a universal sovereign (Psalm 47:2; Quran 112:1–4).⁷ However, Abrahamic monotheism eliminated the pantheon’s hierarchical competition, centralizing divine agency in a single, omnipotent deity. Similarly, Mesopotamian visions of the afterlife—a bleak underworld (Irkalla) devoid of moral judgment—contrast with the Abrahamic eschatologies of resurrection and final accountability (Daniel 12:2; Quran 75:3–4).⁸ These innovations reflect a theological synthesis: adopting Mesopotamian frameworks while infusing them with ethical urgency and hope.

Cultural Adaptation and Identity Formation

The Babylonian Exile (597–538 BCE) served as a crucible for Judaic theological development. Exposed to Mesopotamian myths and legal systems, Jewish scribes engaged in selective adaptation, repurposing regional motifs to fortify communal identity against assimilation.⁹ For example, the Tower of Babel narrative (Genesis 11:1–9) critiques Babylonian ziggurat-building as hubris, polemicizing Mesopotamian religious practice.¹⁰ This dialectic of adoption and rejection underscores how Abrahamic traditions transformed shared cultural materials into vehicles for theological innovation.

Ethical Monotheism as a Mesopotamian Legacy

While Mesopotamian religion emphasized ritual efficacy, Abrahamic faiths prioritized ethical conduct as the locus of divine-human interaction. Prophetic critiques of social injustice (Amos 5:24; Isaiah 1:17) echo earlier Mesopotamian wisdom literature (e.g., Counsels of Wisdom), yet they transcend ritualism by linking morality to covenantal obligation.¹¹ Islam’s zakat (almsgiving) and Christianity’s emphasis on charity further universalize this ethic, transforming regional legal principles into global imperatives.

Conclusion

The Abrahamic faiths did not emerge in a cultural vacuum but engaged dynamically with the Mesopotamian intellectual heritage. By recontextualizing myths, laws, and theological concepts within a monotheistic framework, they forged a distinctive vision of divine unity, moral accountability, and social justice. This synthesis exemplifies the broader process of ancient Near Eastern cross-fertilization, wherein shared cultural materials were reinterpreted to meet evolving spiritual and communal needs. Far from diminishing their originality, this adaptive process underscores the resilience and creativity of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam as they negotiated their place within a pluralistic world.

References

¹ Tigay, Jeffrey H. The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982. DOI: 10.9783/9781512803032.

² Lambert, W. G. “Babylonian Creation Stories.” In Imagining Creation, edited by Markham J. Geller and Mineke Schipper, 15–59. Leiden: Brill, 2008. DOI: 10.1163/ej.9789004163274.i-534.7.

³ Jacobsen, Thorkild. The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976. Google Books.

⁴ Roth, Martha T. Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1997. WorldCat.

⁵ Wright, David P. Inventing God’s Law: How the Covenant Code of the Bible Used and Revised the Laws of Hammurabi. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195304756.001.0001.

References Con’t

⁶ Mendenhall, George E. Law and Covenant in Israel and the Ancient Near East. Pittsburgh: Biblical Colloquium, 1955. JSTOR.

⁷ Frankfort, Henri. Kingship and the Gods: A Study of Ancient Near Eastern Religion as the Integration of Society and Nature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1948. DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226260222.001.0001.

⁸ Bottero, Jean. Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia. Translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001. DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226067180.001.0001.

⁹ Finkelstein, Israel, and Neil Asher Silberman. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New York: Free Press, 2001. Google Books.

¹⁰ Scurlock, JoAnn. “The Techniques of the Sacrifice of Animals in Ancient Israel and Ancient Mesopotamia.” Andrews University Seminary Studies 44, no. 1 (2006): 13–49. Academia.edu.

¹¹ Lambert, W. G. Babylonian Wisdom Literature. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1960. Internet Archive.