The Moche civilization, flourishing between 100 and 800 CE along Peru’s northern coast. They are best known for their striking ceramics and monumental architecture. Yet their metallurgical achievements are equally remarkable. At the site of Loma Negra, archaeologists uncovered copper artifacts plated with gold and silver. Using a process that modern science identifies as electrochemical replacement plating. Unlike modern electroplating, which requires an external electrical current, the Moche relied on chemical reactions alone. Their success demonstrates a mastery of chemistry centuries before the discipline was formally defined.

The implications of this discovery are profound. By transforming base copper into objects that appeared to be solid gold or silver. The Moche elevated ceremonial and elite artifacts into symbols of divine power. This was a technological innovation that reinforced social hierarchies, conserved scarce resources, and showcased the ingenuity of a culture often underestimated in discussions of ancient science.

The Loma Negra Finds

The cemetery at Loma Negra, first exposed by looters in 1969, yielded an extraordinary collection of metal artifacts. Unlike other sites dominated by ceramics, this burial ground was rich in copper objects that had been gilded or silvered. Among the finds were ear ornaments, gilt copper bands, profile masks, and silvered cones. Many of which showed uniform coatings of precious metals even along edges and in surface irregularities.

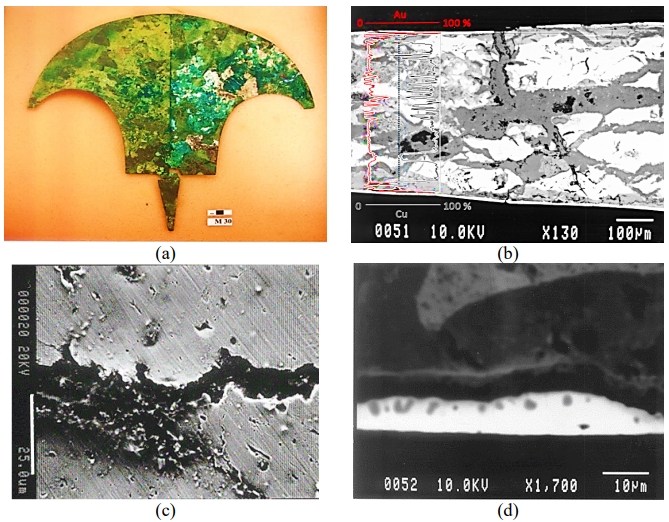

Detailed metallographic analysis revealed that these coatings were extremely thin, often less than one micron in thickness, but remarkably even. They covered not only flat surfaces but also declivities, holes for dangles, and other irregular features. This uniformity suggested a process far more sophisticated than hammering foil or applying molten gold. The evidence pointed toward a chemical technique that deposited precious metals across every exposed surface.

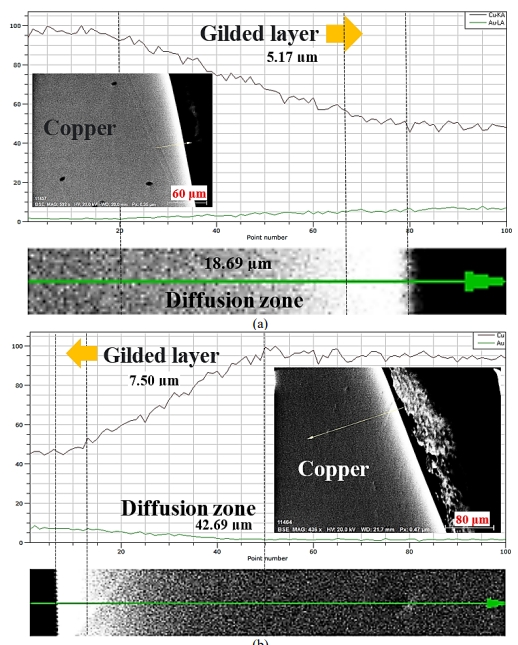

Image above, Backscattered images of the cross-section of the copper substrate after (a) 3 min and (b) 6 min in the electrolytic solutionSource:10.1088/1742-6596/2118/1/012015 CC BY 3.0

The discovery also expanded the known reach of Moche influence. Previously, scholars believed the Moche heartland was confined to valleys between the Chicama and Virú rivers. The presence of Moche‑style ceramics and metalwork in the upper Piura River valley demonstrated that their cultural and technological influence extended much farther north. This reshapes our understanding of their geographic scope.

Evidence of Electrochemical Plating

Microscopic examination of Loma Negra artifacts and Dos Cabezas finds reveal a solid‑state diffusion zone between the gold and copper layers. This indicated that after the gold was deposited, the objects were heated. Thus allowing atoms to diffuse across the interface and strengthening the bond. Importantly, there was no evidence of mercury gilding, foil welding, or immersion in molten gold, methods known in other metallurgical traditions.

Instead, the coatings resembled modern electrodeposits, though achieved without electricity. The researchers concluded that the Moche had discovered a form of electrochemical replacement plating, in which copper immersed in a gold‑bearing solution underwent a chemical exchange: copper atoms dissolved while gold ions precipitated onto the surface. The result was a thin but brilliant layer of gold that adhered to the copper substrate.

This process was replicated experimentally. Gold was dissolved in a heated solution of common salt (NaCl), potassium nitrate (KNO₃), and alum (KAl(SO₄)₂·12H₂O). When copper was introduced, gold plated onto its surface. Heating the plated copper at 500–800 °C produced durable diffusion bonds, closely matching the microstructures observed in the ancient artifacts. The experiments confirmed that the Moche process was both chemically plausible and archaeologically consistent.

Natural Sources of Moche Plating Chemicals

| Chemical | Formula | Likely Natural Sources in Andean Context | Notes on Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salt | NaCl | – Coastal salt flats and evaporite deposits – Seawater evaporation ponds along Peru’s northern coast | Salt was abundant and widely used in Andean societies for food preservation and ritual. |

| Potassium Nitrate (Saltpeter) | KNO₃ | – Natural nitratine deposits in arid soils (esp. Atacama Desert) – Crystalline efflorescence from dung heaps or compost pits – Leached wood ash combined with nitrogen-rich organic matter | Known to form in dry climates; the Andes provided both desert nitrate deposits and organic sources. |

| Alum | KAl(SO₄)₂·12H₂O | – Alunite mineral in volcanic zones – Alum-rich clays near geothermal springs – Evaporite basins with sulfate-rich waters | Volcanic activity along the Andes made alum-bearing minerals accessible. Used historically for dyeing and tanning. |

Silvering Techniques

The Moche also applied similar methods to silver. Some profile masks and ornamental cones were silvered on their front surfaces, though the coatings were even thinner and more fragile than the gold layers. Experimental replication showed that silver could be dissolved in comparable solutions, with silver chloride precipitating out. By neutralizing the solution with calcium carbonate, artisans could create a slurry or paste that deposited silver when rubbed onto copper.

Although corrosion has obscured much of the silver on surviving artifacts, microscopic analysis revealed traces of grain boundary diffusion, proving that silver plating was achieved through the same combination of chemical deposition and heat treatment. These findings demonstrate that Moche metallurgists were versatile, adapting their techniques to different metals..

Cultural and Symbolic Dimensions

The technological sophistication of Moche gilding shouldn’t be separated from its cultural meaning. In Andean cosmology, gold symbolized the sun, divine authority, and immortality, while silver represented the moon, fertility, and cycles of renewal. By plating copper with these metals, artisans imbued objects with cosmic significance. What appeared to be solid gold or silver artifacts carried immense prestige, reinforcing the authority of rulers, priests, and warriors.

Equally important was the economic dimension. Gold and silver were relatively scarce, and plating allowed the Moche to conserve resources while still achieving the desired visual effect. This efficiency ensured that elite classes could display wealth and power without exhausting precious reserves. Metallurgy thus became a tool of social engineering, shaping perceptions of abundance and divine favor.

Ancient Innovation Versus Modern Technology

Comparing Moche plating with modern electroplating highlights both parallels and distinctions. Modern electroplating relies on external electrical currents to deposit metal ions, producing thick, uniform coatings. The Moche, by contrast, relied on chemical replacement reactions, achieving thin but visually striking layers. While modern methods are more efficient and controllable, the Moche process demonstrates that ancient artisans could achieve comparable results through empirical experimentation.

For centuries, scholars assumed that electroplating was a strictly modern invention, first documented in the early 19th century when Luigi Brugnatelli applied Alessandro Volta’s discoveries in electricity to deposit gold onto silver.

This comparison underscores a broader truth: innovation is not confined to modernity. The Moche lacked electricity, microscopes, and chemical theory, yet they manipulated matter in ways that reveal a profound understanding of natural processes. Their achievements remind us that technological sophistication were present in ancient times, driven by necessity, symbolism, and creativity.

Conclusion: Rethinking Ancient Science

The metallurgical discoveries at Loma Negra compel us to rethink the narrative of ancient technology. The Moche were not primitive artisans but pioneers of chemical engineering, mastering both depletion gilding and electrochemical replacement plating centuries before modern science formalized these processes. Their work transformed copper into objects of divine brilliance, conserving resources while reinforcing social hierarchies and religious symbolism.

By recognizing the Moche as innovators, we expand our appreciation of human ingenuity across time and place. Their legacy challenges the assumption that advanced science is a product of modernity alone and invites us to see ancient metallurgy as a field of experimentation, adaptation, and cultural meaning. In the brilliance of their gilded artifacts, we glimpse not only the power of chemistry but the enduring human drive to transform the ordinary into the extraordinary.

For more ancient science read Ancient Mayan Masonry Science