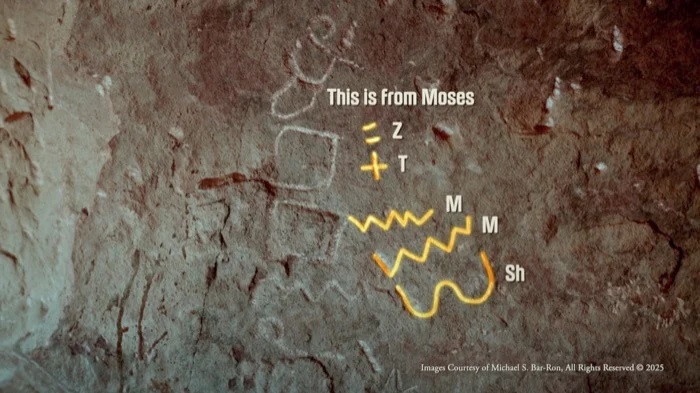

A mysterious inscription potentially linked to Moses has surfaced in an ancient Egyptian mine, stirring debate about its connection to the biblical Exodus. Discovered at Serabit el-Khadim in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, the 3,800-year-old Proto-Sinaitic markings, etched into the rock walls of Mine L, may read “zot m’Moshe,” Hebrew for “This is from Moses.” This finding, proposed by researcher Michael Bar-Ron, could tie directly to the biblical figure who led the Israelites out of slavery, though skepticism from mainstream scholars urges caution. The discovery, challenges long-held assumptions about the historical Moses and the origins of the Hebrew alphabet.

The Discovery at Serabit el-Khadim

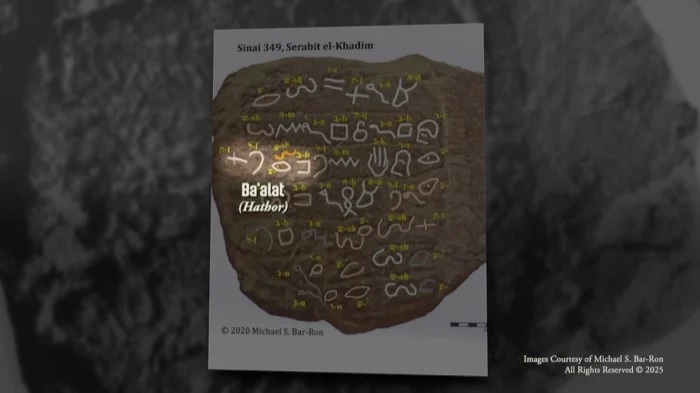

In the early 1900s, archaeologists first uncovered over two dozen Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions at Serabit el-Khadim, a turquoise mining site active during Egypt’s 12th Dynasty, around 1800 BCE. These texts, among the earliest known alphabetic scripts, were likely penned by Semitic-speaking laborers. Unlike the complex Egyptian hieroglyphs with their 800 symbols, Proto-Sinaitic used just 22 letters, making writing accessible to the masses. Bar-Ron, who spent eight years studying high-resolution images and 3D scans at Harvard’s Semitic Museum, suggests one inscription, Sinai 357, could bear Moses’ name. His academic advisor, Dr. Pieter van der Veen, supports this reading, noting its clarity, though the study awaits peer-reviewed publication.

The site itself, nestled at the foot of Jebel Saniyah and Jebel Ghoriba, aligns with some scholars’ proposals for the biblical Mount Sinai and Mount Horeb. The inscriptions reveal a cultural clash, with references to the Hebrew God “El” and defaced carvings of the Egyptian goddess Hathor, also known as Baʿalat. This tension mirrors the biblical narrative of Moses and the Israelites rejecting idol worship, particularly the golden calf, which some connect to Hathor. A burned temple dedicated to Baʿalat, built by Pharaoh Amenemhat III, further hints at a violent rejection of Egyptian religious practices, likely by Semitic workers.

Decoding the Proto-Sinaitic Script

Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions represent a pivotal moment in human history: the birth of the alphabet. Unlike earlier cuneiform, a logo-syllabic system with hundreds of symbols representing words and syllables, Proto-Sinaitic used just 22 letters to denote individual sounds. Also different from Hieroglyphs, which required extensive training, this script’s simplicity suggests it was used by common laborers, possibly including early Hebrews. Bar-Ron’s analysis groups the inscriptions into five categories, including dedications to Baʿalat, invocations of El, and texts showing later defacement. Some carvings express despair, such as one reading, “Bring Baʿalat joy, but there is no strength. We will die.” Others, altered by El-worshipping scribes, reflect a shift toward monotheism, a hallmark of early Israelite faith.

The phrase “zot m’Moshe” appears near Sinai 357 in Mine L, alongside another inscription referencing a figure named Arba, possibly a Levitical leader, urging readers to “hearken” to the message. A second potential reference to Moses in nearby carvings adds intrigue, though its context remains unclear. Bar-Ron emphasizes his cautious approach, seeking alternative explanations to avoid sensationalism.

His methodology, rooted in consistent rules for reading the script’s direction and letter forms, traces each character to its hieroglyphic roots, offering a framework for future studies.

Challenges in Interpretation

Deciphering Proto-Sinaitic script is no small feat. The characters, etched without spaces or clear direction, can be read left, right, or vertically, complicating translations. Dr. Thomas Schneider, an Egyptologist at the University of British Columbia, dismisses Bar-Ron’s claims as “completely unproven,” warning that arbitrary letter identifications risk distorting history. Despite this, van der Veen’s endorsement and Bar-Ron’s rigorous use of high-resolution casts lend credibility to the Moses hypothesis. The inscriptions’ connection to Northwest Semitic languages, closely related to biblical Hebrew, supports the idea of a Semitic presence at the site, potentially linked to figures like Joseph, who rose to power in Egypt according to Genesis.

Historical and Biblical Connections

The possibility that these inscriptions reference Moses directly challenges the lack of archaeological evidence for his existence. The Bible describes Moses as leading the Israelites out of Egypt, receiving the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai, and confronting the golden calf worship.

The defaced Baʿalat inscriptions and the burned temple at Serabit el-Khadim align with this narrative of rejecting idolatry.

References to a “Gate of the Accursed One,” likely tied to Pharaoh’s authority, suggest resistance against Egyptian rule, echoing the Exodus story. Amenemhat III, who reigned during the 12th Dynasty, is proposed by some as the pharaoh of the Exodus, given his extensive building projects and the Semitic presence in Egypt at the time.

Nearby artifacts, like the Stele of Reniseneb and a seal of an Asiatic official, point to significant Semitic influence, possibly linked to Joseph’s role as a high-ranking official. Inscriptions mentioning names like Levi, Issachar, and Qeni (a Kenite, related to the Midianites) further tie the site to early Israelite tribes. These names, alongside references to El and Yahweh, suggest Serabit el-Khadim was a cultic center for early Hebrew worship, distinct from other proposed Sinai locations.

El Versus Baʿalat: A Religious Clash

The inscriptions reveal a spiritual battle between El-worshippers and devotees of Baʿalat. Some texts show Baʿalat’s name scratched out, replaced with references to El, suggesting a deliberate effort to assert monotheistic beliefs. This mirrors the biblical account of Moses destroying the golden calf and reinforcing worship of Yahweh. Hieroglyphic inscriptions at the site also mention Sopdu, an Egyptian deity equated with El, known as the “Guardian of the Borders” and linked to the Western Asiatic population in Goshen, where the Israelites reportedly lived. This overlap between Proto-Sinaitic and hieroglyphic records strengthens the case for a Hebrew presence in the region.

Scholarly Debate and Future Research

Bar-Ron’s findings, while compelling, face scrutiny for their lack of peer-reviewed validation. Dr. Thomas Schneider’s critique highlights the difficulty of interpreting Proto-Sinaitic script, where letter shapes and reading directions remain contentious. Yet, Bar-Ron’s upcoming MA and PhD theses aim to formalize these findings, potentially reshaping our understanding of early Israelite history.

The discovery’s significance extends beyond proving Moses’ existence. It underscores the development of the alphabet, a Semitic innovation that transformed communication. The inscriptions’ references to slavery, overseers, and resistance align with biblical themes, offering a glimpse into the lives of ancient laborers. Bar-Ron’s call for further research emphasizes the need for rigorous scholarship to test these claims against academic standards.

Historical Significance

The Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions at Serabit el-Khadim offer a tantalizing link to the biblical Moses, challenging skeptics and believers alike to reconsider the Exodus narrative. Whether or not “zot m’Moshe” definitively points to the biblical figure, the inscriptions reveal a vibrant Semitic culture in ancient Egypt, with ties to early Hebrew worship and the alphabet’s origins. As Bar-Ron and his mentors continue their work, the site may yet yield more clues about the historical roots of the Israelites, bridging faith and archaeology in a way that invites us to keep thinking.