A mysterious underworld beneath the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent in Teotihuacan, Mexico. It has captivated archaeologists and historians with its enigmatic purpose and rich artifacts. Discovered in 2003, this tunnel, sealed for nearly 1,800 years, offers a window into the Teotihuacan culture’s cosmology. Excavations, aided by robotic technology, uncovered liquid mercury, pyrite-coated spheres & jade figurines. Along with and organic & human remains. Suggesting a ritual space tied to the underworld. This article explores the tunnel’s discovery, its contents, the culture behind it. Theories for its sealing, which draw from archaeological findings and expert interpretations.

Discovery of the Tunnel: A Rainy Revelation

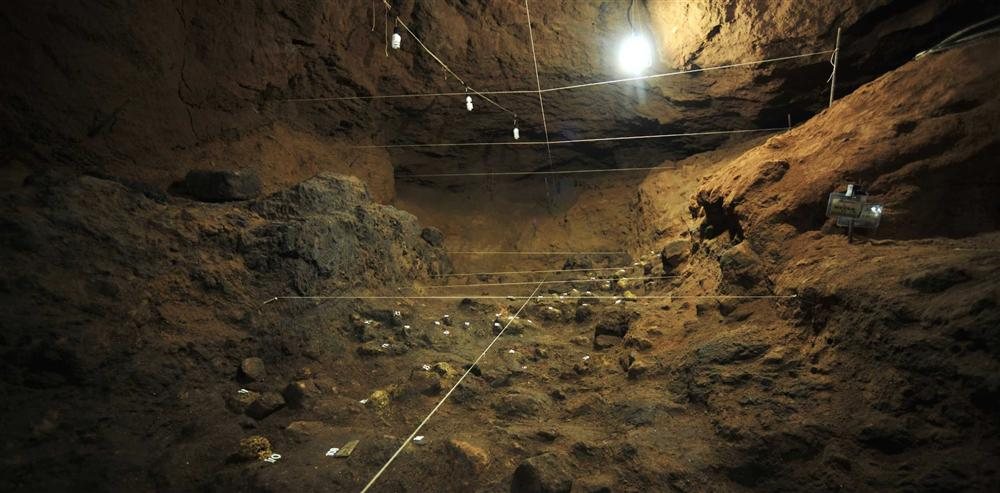

In October 2003, heavy rainfall at Teotihuacan, exposed a sinkhole near the Pyramid. The sinkhole, revealed a descending cylindrical shaft. Archaeologist Sergio Gómez Chávez, entered the shaft and found a 103-meter-long, man-made tunnel, sealed around 200–250 CE. The tunnel, filled with 1,000 tons of earth and blocked by stones, hinted at a significant ritual purpose. Its alignment beneath the pyramid’s center suggested a connection to Teotihuacan’s cosmological beliefs, sparking a decades-long excavation effort.

The discovery paralleled an earlier tunnel under the Pyramid of the Sun, indicating a cultural practice of subterranean ritual spaces. Gómez’s team erected a tent to protect the site from millions of annual visitors, ensuring careful exploration. Initial surveys, including digital mapping by 2005, confirmed the tunnel led to three chambers, setting the stage for advanced technological interventions.

Robot Expeditions: Unveiling the Underworld

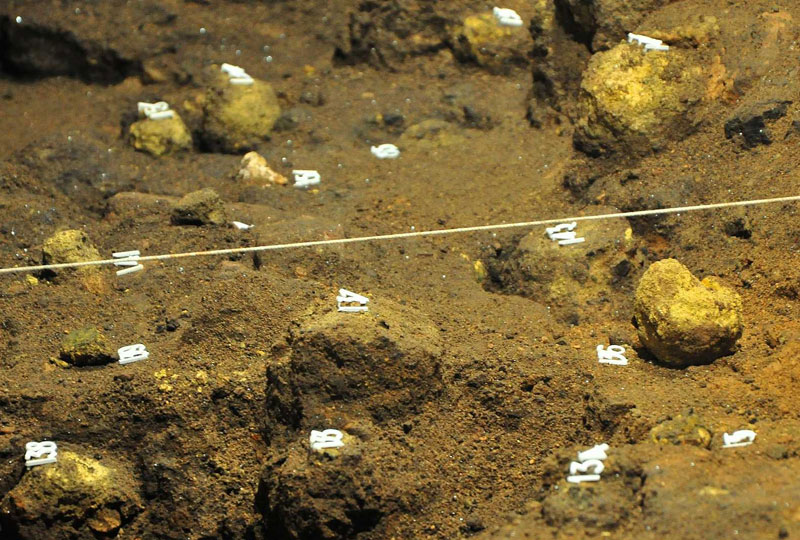

The tunnel’s narrow, muddy conditions and toxic substances like liquid mercury posed risks to human excavators. To overcome these challenges, Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) deployed a small robot in November 2010. Equipped with cameras and infrared scanners, Tláloc II navigated the tunnel, capturing images of its structure and artifacts. Between 2010 and 2015, robotic explorations mapped three chambers at the tunnel’s end using ground-penetrating radar and laser scanning. These scans provided a detailed view of the hidden structures. In the process, researchers uncovered over 100,000 artifacts.

These expeditions confirmed the tunnel’s role as a representation of the mysterious Mesoamerican underworld. The chambers contained liquid mercury, pyrite-coated clay spheres, jade statues, obsidian blades, and organic remains, all meticulously placed. The robots’ non-invasive approach preserved the fragile environment, allowing archaeologists to study the tunnel’s contents without compromising its integrity.

Artifacts and Their Cosmic Significance

The tunnel’s artifacts paint a vivid picture of Teotihuacan’s religious practices. Liquid mercury, discovered in 2015 in one of the chambers, likely symbolized an underworld river or lake. A rare find in Mesoamerican archaeology. Its reflective surface, suggest a connection to elite rituals. Possibly indicating a royal tomb, though as of yet, none has been found.

Hundreds of clay spheres, coated with pyrite (iron sulfide, often called “fool’s gold”), were scattered throughout the tunnel. These spheres, now oxidized to jarosite, once shimmered like stars under torchlight. They complemented the pyrite-dusted walls to create a cosmic effect.

Archaeologist George Cowgill noted their uniqueness, suggesting they represented celestial bodies in the mysterious Mesoamerican underworld.

Jade figurines, over 4,000 in number, included four anthropomorphic statues positioned to gaze at the axis mundi. The axis mundi is the cosmic axis linking earth, sky, and underworld. These likely depicted deities or founding shamans. Obsidian blades, ceramics (including a Tlaloc-shaped pot), and organic remains (preserved flowers, cocoa beans, jaguar skulls, and human hair) point to complex rituals involving fire and sacrifice. A bonfire, consisting of bouquets of 40–60 flowers, marked the tunnel’s final use before sealing.

Caribbean conch shells, shell necklaces mimicking human teeth, and rubber balls tied to the Mesoamerican ballgame were also found. Along with an amber sphere, possibly containing tobacco residue, suggests hallucinogenic rituals, adding to the tunnel’s sacred aura.

The Teotihuacan Culture: Builders of the Tunnel

The tunnel was crafted by the Teotihuacan culture, a multiethnic civilization thriving from 100 BCE to 750 CE, distinct from the later Aztecs who revered the site as “the place where the gods were created.” Teotihuacan, one of Mesoamerica’s largest cities, peaked around 200–450 CE with up to 150,000 residents. Its grid layout, centered on the Avenue of the Dead, and monumental pyramids reflect advanced engineering and cosmological focus.

The Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, built around 150–200 CE, was a religious hub associated with Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent deity, and Tlaloc, the storm god. Over 100 sacrificial victims beneath the pyramid, some with cranial deformation, indicate rituals tied to warfare or rulership. The tunnel’s design, with chambers representing the four cosmic directions, underscores Teotihuacan’s obsession with the mysterious Mesoamerican underworld, a realm of water, deities, and creation.

Unlike the Aztecs, who rose in the 14th century CE, Teotihuacan left no written records, leaving their ethnicities and language uncertain. Their influence, seen in jade, obsidian, and pyrite use, shaped later Mesoamerican cultures. But the tunnel’s sealing predates Aztec presence by over a millennium.

Why and Who Sealed the Tunnel?

The tunnel’s sealing around 200–250 CE, dated through radiocarbon analysis of organic artifacts like flowers and wood, was a deliberate act requiring significant labor. Priests or elites likely orchestrated it, given the tunnel’s ritual significance. Radiocarbon dating, corroborated by stratigraphic analysis and ceramic styles from the Tlamimilolpa phase (200–350 CE), places the sealing during Teotihuacan’s peak, ruling out decline or invasion.

The primary theory suggests a ritual closure to consecrate the mysterious Mesoamerican underworld. The tunnel’s artifacts (mercury, pyrite spheres, jade) were offerings for deities or rulers, possibly marking a cosmic cycle’s end or a ruler’s inauguration. Watermarks indicate intentional flooding, emulating a primordial sea, supporting this ceremonial purpose.

Sergio Gómez proposed the sealing might protect a royal tomb, given the mercury’s rarity and the pyramid’s sacrificial victims. However, no tomb has been confirmed, and scholars like Cowgill argue the tunnel was primarily a ritual space. The bonfire and careful artifact placement suggest a final ceremony before sealing, preserving the sacred environment.

Ongoing Mysteries and Future Exploration

The tunnel’s purpose remains partially speculative due to Teotihuacan’s lack of written records. The absence of a confirmed tomb keeps the royal burial theory open, while fringe ideas about energy generation lack evidence. Ongoing excavations, supported by INAH, may uncover new clues, but the tunnel’s pristine state, preserved since 250 CE, underscores its sanctity.

The mysterious Mesoamerican underworld beneath the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent continues to intrigue. Its artifacts, revealed through robotic exploration, highlight Teotihuacan’s sophisticated cosmology. As research progresses, this subterranean marvel promises to deepen our understanding of a civilization that shaped Mesoamerica.

Sources:

- Archaeology Magazine (2015): “Liquid Mercury Discovered Beneath Teotihuacan Pyramid”

- PBS Secrets of the Dead (2016): “Teotihuacán, the City of the Gods”

- INAH reports and The Mercury News (2017) on the de Young Museum exhibition.

- Buckley GM, Clayton SC, Gómez Chávez S, et al. Refining Ceramic Chronology and Epiclassic Reoccupation at La Ventilla, Teotihuacan Using Trapezoidal Bayesian Modeling. Radiocarbon. 2023;65(3):617-641. doi:10.1017/RDC.2023.21