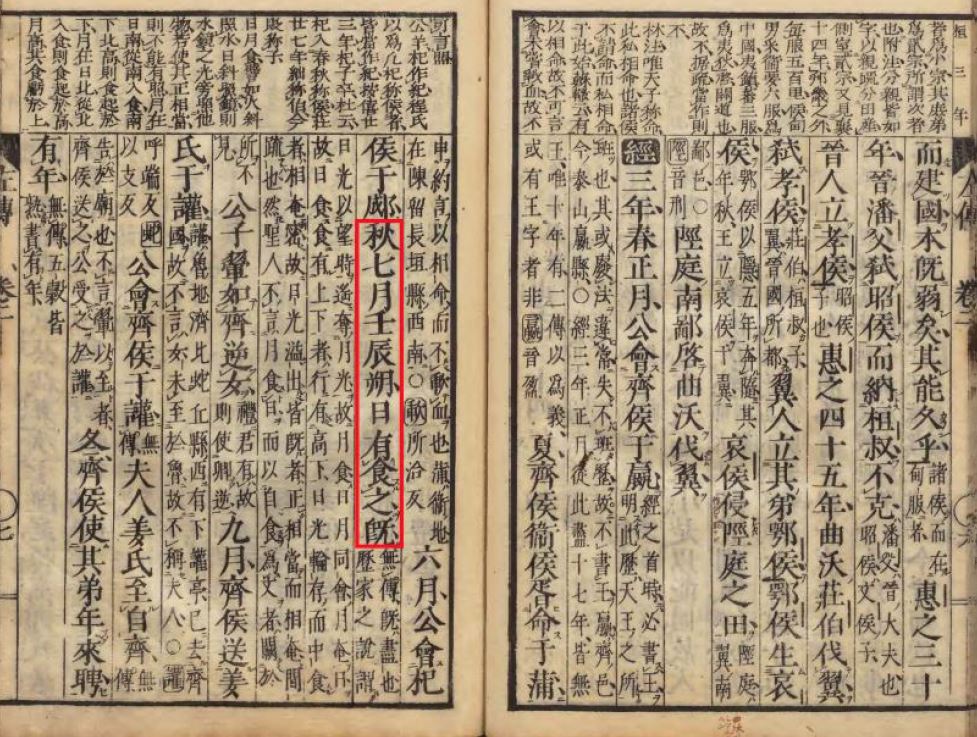

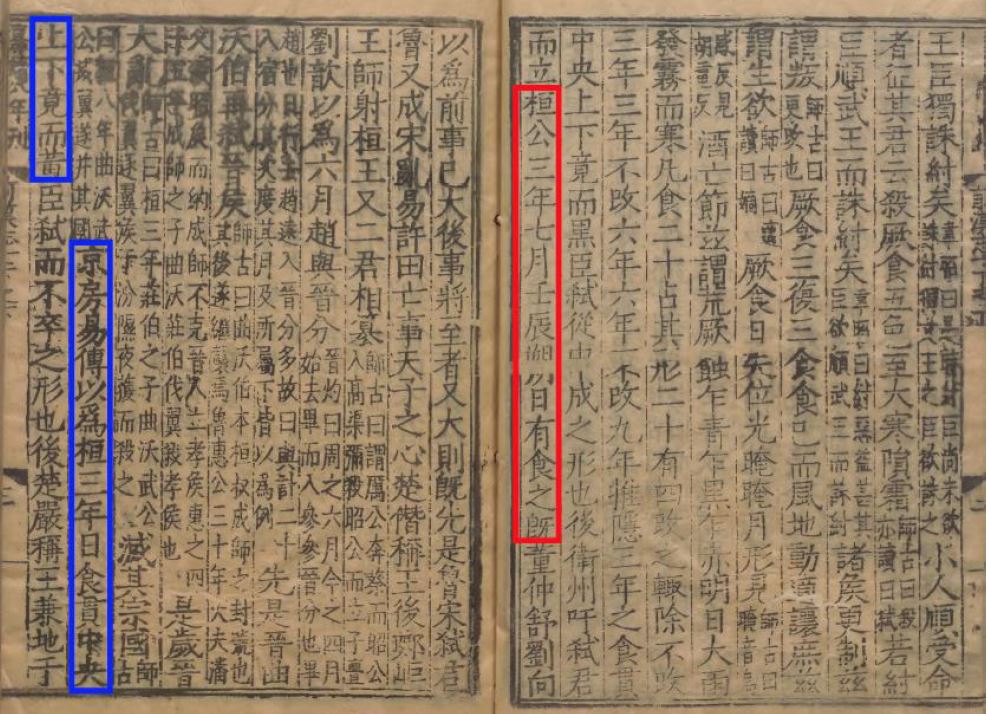

In 709 BCE, observers in the Duchy of Lu in ancient China documented a total solar eclipse. The Chūnqiū chronicles record the Sun as “totally eclipsed,” making this the earliest datable written account of totality. Centuries later, the Hànshū added a striking detail: the eclipsed Sun appeared “completely yellow above and below.” Modern researchers interpret this as a possible description of the solar corona. The outer atmosphere of the Sun visible only during total eclipses.

The significance of this record lies not only in its age but in its precision. By correcting the archaeological coordinates of Qūfù, the Lu capital, scientists placed the city firmly within the eclipse path. This correction allowed them to recalculate Earth’s rotation speed and contextualize solar activity during the late eighth century BCE

Earth’s Faster Rotation

The study recalculated ΔT (Delta‑T), the offset between atomic time and Earth’s rotation. For 709 BCE, ΔT was revised to 20,264–21,204 seconds. This higher value means Earth’s rotation was faster than today, producing shorter days. The slowdown over millennia is driven mainly by tidal friction from the Moon. But precise eclipse records like this one serve as rare calibration points. The correction also forced revisions for eclipses in 600 BCE and 548 BCE. They showed that a single mis‑placed coordinate can ripple through centuries of geophysical modeling

A Less Active Sun

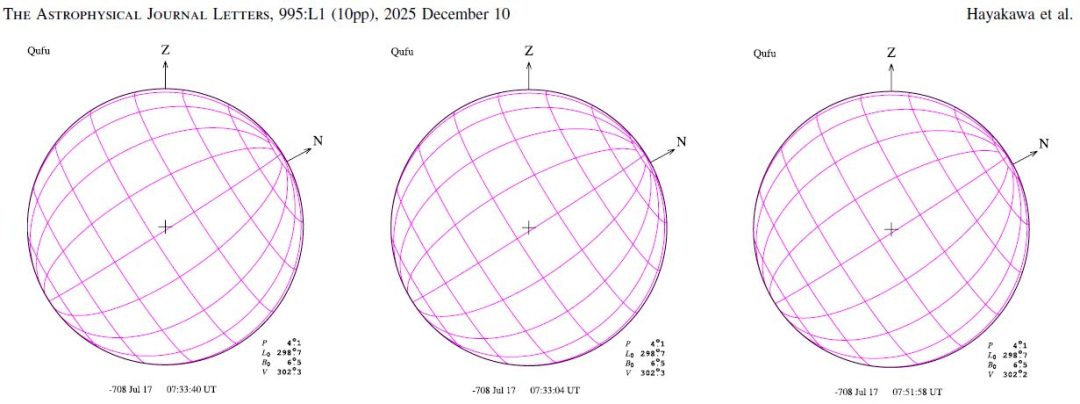

The “yellow above and below” description has been cautiously linked to coronal streamers. When compared with reconstructions of solar cycles from tree‑ring radiocarbon data, the eclipse occurred just after the Neo‑Assyrian Solar Grand Minimum (807–716 BCE). A prolonged lull in solar activity. The orientation of the solar disk during the eclipse suggested streamer belts at latitudes around ±32°. Which are consistent with reconstructions of open solar flux. This supports the conclusion that the Sun was relatively less active at the time. Producing fewer but still visible coronal structures

Comparative Ancient Eclipse Records

The Chinese record is not alone. Other civilizations also documented eclipses that became anchors for chronology and science:

- Assyrian Eclipse (763 BCE): Recorded in cuneiform tablets, this total eclipse over Nineveh is used to fix the chronology of the Assyrian Empire.

- Archilochus’ Eclipse (648 BCE): The Greek poet Archilochus described the Sun vanishing midday, a vivid literary record of totality.

- Thales’ Eclipse (585 BCE): Famously said to have stopped a battle between the Medes and Lydians, this eclipse was later tied to Herodotus’ histories.

- Ugarit Eclipse (1375 BCE): A clay tablet from Syria describes the Sun being “put to shame,” one of the earliest Mesopotamian eclipse records

These accounts, like the Chinese record, were often framed as omens, but they now serve as scientific calibration points for Earth’s rotation and solar cycles. But within that is an Omen in of itself.

A vanishing spectacle: why total eclipses will someday end

This discovery is also a reminder that totality itself is a temporary privilege. The Moon is receding from Earth by a few centimeters per year due to tidal interactions and the Earth’s rotation continues to slow. As it drifts outward, its apparent size shrinks against the Sun. There will come a time when the Moon no longer fully covers the solar disk. Turning future “total” events into annular or partial eclipses. The authors focus on a beginning, the oldest datable total eclipse, at the front of a long arc whose end is already written in orbital mechanics. The geometry that allowed coronal streamers to be seen naked‑eye in 709 BCE will not persist forever; the shadow will keep reaching us, but the perfect fit will be gone.

Conclusion

The 709 BCE total eclipse in the Duchy of Lu is the oldest datable written record of totality and perhaps the first glimpse of the corona in human history. By correcting Qūfù’s ancient coordinates and re‑solving ΔT, the authors show Earth rotated faster at that time and position the event near the end of a grand solar minimum. Set alongside Assyrian and Greek accounts, the Lu record forms part of a global chain of eclipse anchors. It also points forward: as the Moon slips away, true totality will disappear, and with it the cleanest view of the Sun’s atmosphere from Earth. The paper is not just about what happened; it is about what will no longer be possible.

For More on Ancient Eclipses Read Here:

Dresden Codex: Unveiling the Mayan Eclipse Table