Introduction: A Land Before the Eagles

Before Roman eagles shadowed Great Britain’s misty isles, vibrant cultures thrived. Tribes, bound by ancient traditions, showed fierce loyalties. Because of this, they held a deep connection to their land. As a result, in the first century BC, pre-Roman Britain culture flourished. It was a mosaic of Celtic tribes. From the Iceni in the east to northern Brigantes, they lived. Each had chieftains, druids, and sacred groves for worship. Hill forts crowned rolling landscapes with earthen ramparts that for instance guarded roundhouse villages where families wove wool.

They forged iron and honored earth’s spirits with rituals. Yet, whispers of a distant empire reached southern shores. The Romans approached, stirring fear and unity among tribes. Therefore, as Roman invasion loomed, coalitions formed and rivalries faded away. For this purpose, brave warriors stood against an unstoppable foe with courage. This tale traces Roman Britain’s rise and its resistance. It covers Hadrian’s Wall, Picts’ defiance, and the empire’s decline. A poet later saw desolation where mighty cultures once stood.

Pre-Roman Britain Culture – A World of Tribes and Traditions

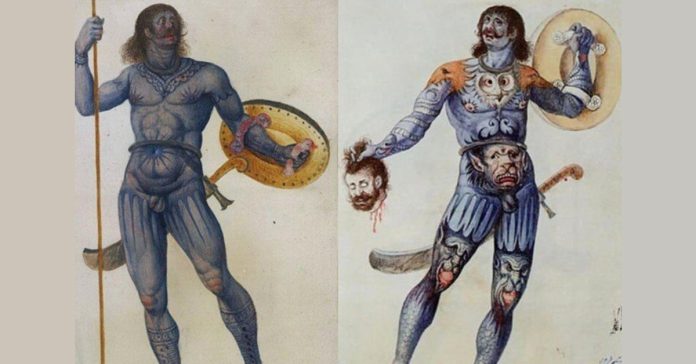

In the first century BC, pre-Roman Britain culture flourished as a patchwork of Celtic tribes with interconnected traditions. For example, the Iceni in East Anglia were renowned for horsemanship, warriors charging into battle with woad-painted bodies, terrifying foes. Julius Caesar noted with horror: “All Britons dye themselves with woad, giving a bluish colour, fearsome in battle.” In addition, the Brigantes, a powerful northern confederation, ruled by chieftains like Cartimandua, stretched influence across the Pennine hills widely. Likewise, in the west, the Silures of modern Wales and Ordovices resisted fiercely, rugged landscapes serving as their natural fortress. These tribes lived in timber-thatch roundhouses, clustered within hill forts like Maiden Castle, hence a Dorset stronghold with ramparts.

Society revolved around kinship, loyalty to chieftains, druids as spiritual leaders, judges, and keepers of sacred oral traditions. They worshipped Cernunnos, horned fertility god, in sacred groves, offering bronze torcs, iron swords to honor earth spirits.

Trade flourished widely, with Cornwall’s rare tin, crucial for bronze, exchanged with continental tribes via the Channel routes. Ironworking produced essential tools, weapons, as blacksmith forges at sites like Danebury Hill Fort reveal through archaeological evidence.

Art thrived in intricate forms. From the swirling patterns on La Tène-style brooches to the carved standing stones of the northern tribes. Festivals marked the solstices, with bonfires lighting the night as communities danced and feasted on roasted boar. Yet, beneath this vibrant culture, tensions simmered. Rivalries between tribes like the Catuvellauni and the Trinovantes often flared into conflict. Thus weakening their unity as a greater threat loomed on the horizon: the Roman Empire.

Roman Invasion Britain Resistance

Coalitions and Brave Battles

As the first century BC drew to a close, whispers of Roman ambition reached Britain’s shores. The Roman Republic, flush with conquests across Europe, Greece, and North Africa, viewed the island as a mysterious frontier. Some, as historian Plutarch recorded, believed Britain was a myth, its “name and story fabricated.” Yet, the allure of its tin, gold, and silver drew Rome’s gaze. Julius Caesar’s invasions in 55 and 54 BC, though unsuccessful, signalled Rome’s intent. His forces faltering in Kent’s marshy lands against fierce resistance. Emperor Augustus planned three invasions, all aborted, and Caligula’s 200,000-man army on the Normandy coast famously gathered seashells instead of conquering. A whimsical failure underscoring Britain’s elusiveness.

The true invasion came in 43 AD under Emperor Claudius, who landed 20,000 men, this being four legions, in Kent. The impending threat galvanized the tribes, forging coalitions as rivalries faded. The Catuvellauni, led by chieftain Caratacus, united with the Trinovantes, setting aside past conflicts to face the Roman eagles. The Iceni, though initially neutral, later joined the resistance under Boudicca’s banner. Caratacus, a master of guerilla warfare, rallied the tribes for a stand on the River Medway, where Britons—painted in woad, wielding spears, and charging with war cries—met the disciplined Roman legions. The battle raged for two days, an unusually long clash for the era, as Roman historian Dio Cassius notes, with the Britons fighting “fiercely” before retreating to the Thames.

The Long Defeat

Despite their bravery, the Britons could not withstand Rome’s mastery of war. The Romans, with their engineering prowess, built bridges across the swampy Essex marshes, outmaneuvering the defenders. After a final bloody clash on the Thames, Claudius arrived with a war elephant, its “heavy thuds” and “rattling chains” shattering British resolve. Caratacus fled west to the Silures, continuing his resistance until captured in 51 AD. The Roman victory was sealed, but the spirit of defiance lingered, setting the stage for future rebellions.

Roman Establishment – From Conquest to Civilization

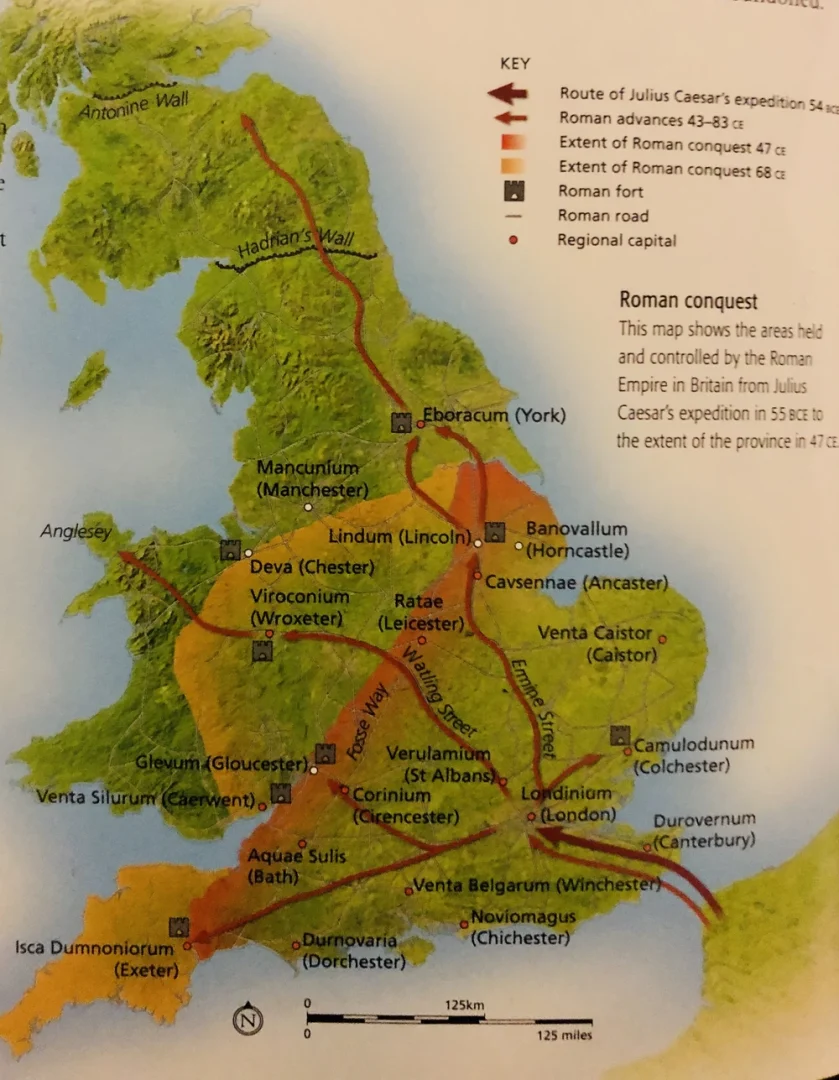

With Britain subdued, Rome established its rule, transforming the island into the province of Britannia. Cities like Londinium (London) and Camulodunum (Colchester) sprang up rapidly, their forums, theatres, and villas adorned with mosaics, baths, and underfloor heating. Trade flourished, bringing wine, olive oil, and even spices from India, while Britain supplied tin, gold, and silver. The Romans, devotees of urbanism, built roads connecting these hubs, facilitating the movement of goods and legions. Luxurious villas dotted the countryside, their owners enjoying imported red gloss pottery from Gaul and pepper from India, as archaeological finds reveal.

Yet, Rome’s grip was never secure. In 60 AD, Boudicca of the Iceni led a massive rebellion, burning Londinium, Camulodunum, and Verulamium (St. Albans). Her forces, numbering tens of thousands, were driven by rage at Roman oppression, her daughters’ assault by Roman soldiers and the enslavement of her people. Roman historian Tacitus describes her rallying cry: “We Britons are used to women commanders in war… we fight for our freedom!” Despite initial victories, Rome crushed the revolt, and Boudicca died, likely by poison, leaving a legacy of resistance.

To secure the northern frontier, Emperor Hadrian ordered the construction of Hadrian’s Wall in 120 AD, a 135-kilometer barrier of igneous dolerite stretching from coast to coast. Fortified with garrisons, it marked the empire’s limit against the unconquered tribes of Caledonia. The Antonine Wall, built 160 kilometers north in 142 AD, was abandoned due to the region’s harsh terrain, its stones left to crumble into the Scottish moors. Roman coins found north of Hadrian’s Wall suggest payments to the tribes to hold back attacks, a desperate measure to maintain peace.

Picts and Hadrian’s Wall – A Frontier of Defiance

The Picts, a fierce confederation in Caledonia, were the bane of Roman Britain. Historian Cassius Dio describes them as inhabiting “wild and waterless mountains… they dwell in tents, naked and unshod, very fond of plundering.” Named “Picts” (from Latin for “painted”) for their war paint, they left behind standing stones adorned with mesmerizing swirls, a cultural legacy that endures. Their mastery of guerilla warfare halted Roman expansion, forcing the construction of Hadrian’s Wall. A writing tablet from 92 AD, found in a fort’s rubbish heap, captures Roman frustration: “The Britons are unprotected by armour… the cavalry do not use swords.”

In 367 AD, the Great Barbarian Conspiracy exposed the wall’s vulnerability. Roman soldiers, battered by harsh winters and meager rations. Known words are: “cold that bit at their feet” and “not enough beer”, ended in mutiny, allowing Picts to cross the wall. Historian Ammianus Marcellinus recounts the chaos: “The Attacotti and Scots were ranging wildly… while the Gallic regions were harassed by the Franks and Saxons with cruel robbery, fire, and murder.” This coordinated assault by multiple tribes overwhelmed Roman defences, sacking cities and spreading terror. General Flavius Theodosius restored order, but the empire’s confidence was shattered, marking a turning point in the Picts’ resistance and Hadrian’s Wall decline.

The Decline of Roman Britain – A Slow Unraveling

Roman Britain’s decline was a slow unravelling, driven by internal flaws and external pressures. The province required a massive army of 40,000 soldiers to defend against Picts, Scots, and Saxons, making governors powerful but tempting them to march on Rome during imperial crises. Claudius Albinus in 195 AD, Magnus Maximus in 383 AD, and Constantine III in 407 AD each took their legions to challenge for the imperial throne, leaving Britain undefended. Maximus’ departure marked the end of Roman rule in Wales and the northern Pennines, with no artefacts found after 383. Constantine III’s exit in 407 AD prompted Emperor Honorius’ 410 AD decree, telling Britons to “look to their own defences.”

In short, the economic decline exacerbated the crisis. As a result, trade collapsed, pottery production dwindled, and iron prices soared, as evidenced by “coffins… sealed without nails.” Meanwhile, In Canterbury, sewers clogged, and silt filled public baths, the very symbols of Roman civilization. The Great Barbarian Conspiracy of 367 AD, combined with civil wars and barbarian incursions across the empire, weakened Rome’s grip. By the early 5th century, cities like Londinium were deserted, their forums quarried for stone, and nature reclaimed the streets with “ivy growing over crumbling walls.”

A Poet’s Witness – Desolation Where Cultures Stood

Centuries later, in the eighth or ninth century, an unknown poet stood amidst the ruins of a Roman town today believed to be likely Bath, penning The Ruin. So enters the The Old English poem, scarred by fire, laments a lost world: “Death took all the brave men away… the city decayed… these buildings grow desolate.” Where once mighty cultures stood. The vibrant tribes of pre-Roman Britain, the defiant Picts, and the grandeur of Roman cities, of these only desolation remained. The poet, clambering over shattered masonry, imagined the “cavernous halls” and the “work of giants,” pondering their builders’ fate. The ruins of Bath, Londinium, and York, overtaken by frogs and water voles, whispered of a golden age erased by time, leaving only poetry to mourn where once a clash of cultures shaped a land.

Conclusion: Echoes of a Lost World

The tale of Roman Britain, from its pre-Roman glory to its haunting desolation, is a saga of resilience and ruin. The tribes’ coalitions and brave battles could not withstand Rome’s mastery, yet their resistance, embodied by the Picts at Hadrian’s Wall, left an indelible mark. Rome’s establishment brought grandeur, but its decline revealed the fragility of empire. Through The Ruin poem, we hear the echoes of a lost world, where mighty cultures stood and fell, urging us to ponder the mysteries of history and the lessons they whisper through the ages.

Here is the Poem in full: Click Here