The Atlantic Rock Art Culture

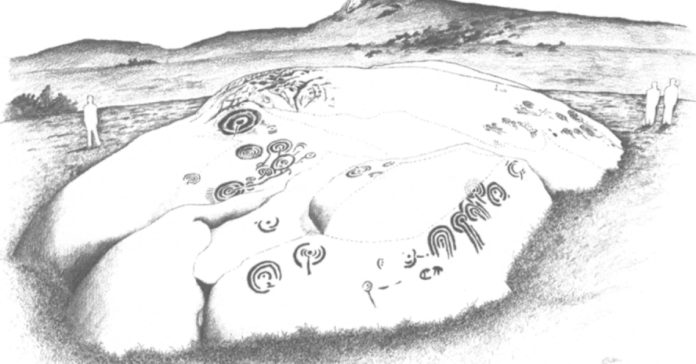

Across the rugged cliffs of northern Britain and the weathered outcrops of northern Spain, stones bear silent witness to a past we strain to fathom. Atlantic rock art as it is called, represented by cup marks, spirals and daggers etched into open air—whispers of origins obscured by time. Richard Bradley poses a haunting question: Where did these carvings begin, and what purpose did they serve? Scattered like memories along the Atlantic coast, they link to megalithic tombs, distant shores, and perhaps, as many academics believe, come to be by the sheer human impulse to mark the earth. I personally like to believe that most where done for a purpose, and not out of a whim.

Indelible Record

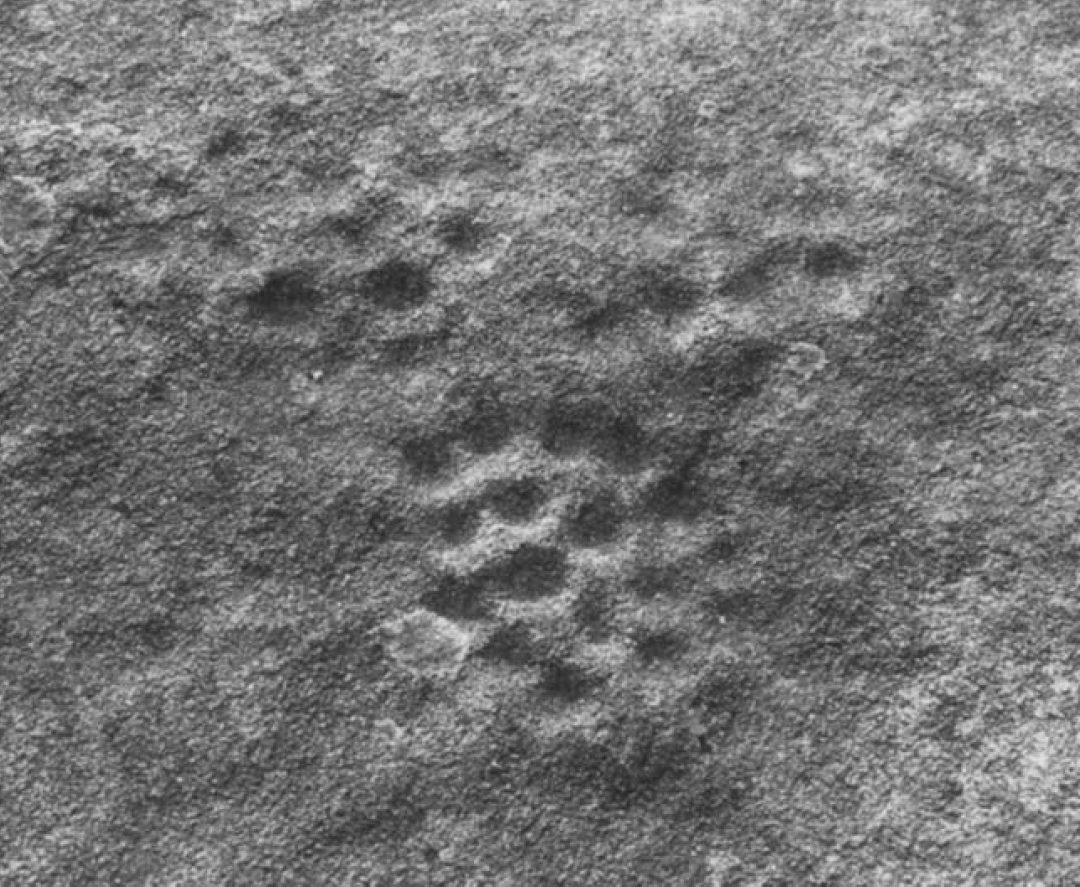

Luckily for us, these petroglyphs endure still, their surfaces weathered yet resolute, holding memories we cannot remember and sights we can only glimpse. In their quiet lines, some academics see a bridge between eras, where hands of Neolithic and Bronze Age artisans working stone, tracing metalwork and idols across landscapes from Galicia to Ireland. For others, the inquiry into their genesis stirs a deeper wonder: What drove these marks, and what tales do they carry across millennia?

Let us pause before these ancient sentinels, their stillness, a canvas for contemplation and ponder the faint, enduring pulse of a world long vanished, yet carved into the very bones of the earth. Living Ghosts of a forgotten era, one we must understand the Mindscape and Landscape of, if we wish to solve these riddles. Modern interpretations, based on our cultural perception of what was, is not the same of living their lives and seeing the world from their eyes. Without understanding this, this mystery will never be properly solved.

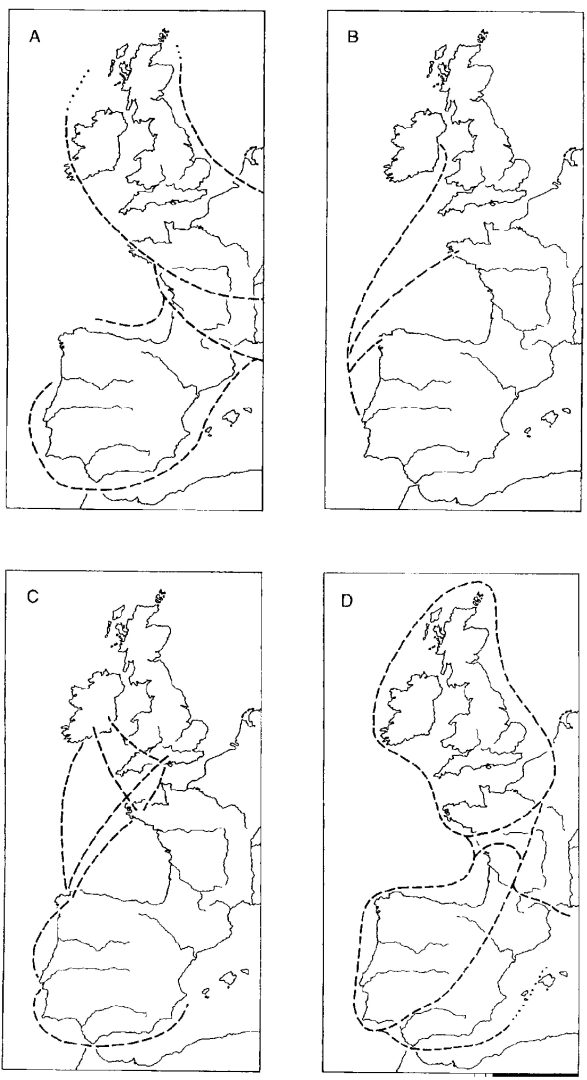

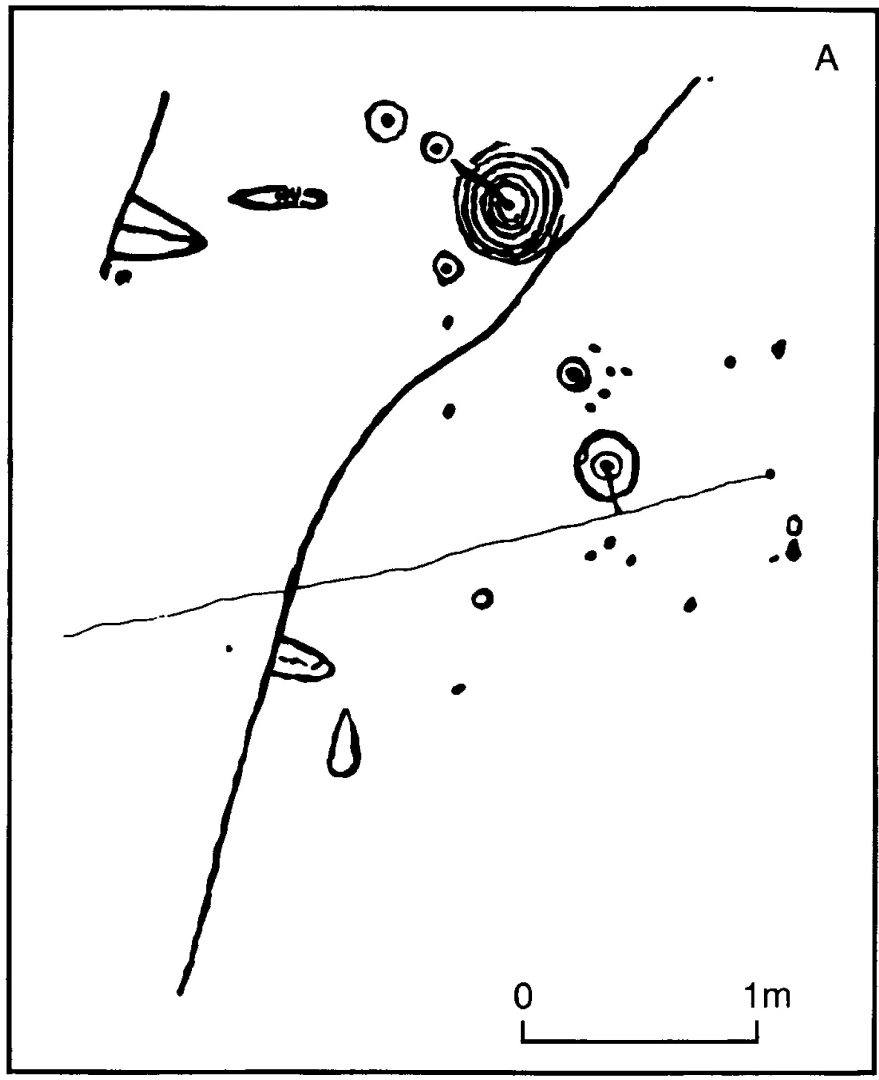

While tracing the Carvings’ Age, the Atlantic rock art’s silent chronology unfolds like a map etched in stone, its timeline pieced together by Richard Bradley’s careful gaze. These carvings, often deemed undatable, yield clues through naturalistic drawings, daggers, axeheads, halberds, linking them to known eras. In Britain, Early Bronze Age barrows like Nether Largie in Argyll and cairns near Stonehenge reveal flat axes and undiagnostic daggers, dating to the period’s dawn, around 2000–1500 BC (Simpson and Thawley, 1972). At Nether Largie, axe carvings overlay older cup marks, suggesting a minimum age for those abstract motifs, their history layered like sediment.

Across the Sea

Across the sea in Galicia, the story deepens: daggers and halberds carved into rock echo Beaker horizon weapons from the Early Bronze Age’s start, circa 2500–2000 BC, while some, like those at Castriño de Conxo, align with the Wessex Culture’s later types (Peña, 1979). Knappers near Glasgow offers a rare twist, a cist with fresh carvings and a Late Neolithic flint axe, hinting at continuity from 3300 BC (Ritchie and Adamson, 1981). Lilburn’s trench, with its spiral-decorated stone and cremations, stretches back to Neolithic barrows around 3300 BC, its wooden echoes buried in time (Moffatt, 1885).

Academics consider these marks, tied to metalwork and reused stones, whisper of a world adapting, its art outlasting its makers. Bradley’s particular quest for making these analogies, is now considered to reveal not just dates, but a rhythm of human hands shaping stone across centuries, a fragile bridge to a past we barely grasp. Well, I here disagree once more, Rock art is not an isolated art or occurring in but a few places, no. It is absolutely global, appearing even, in remote islands standing in the middle of the Oceans. But more importantly, they can date to much further back in time than mentioned by Bradley.

Oldest Rock Art

The very oldest widely recognized rock art example of oldest rock art lies at Cáceres, Spain, It is believed that Neanderthal hands carved and painted at least 64,000 years ago. Uranium-thorium dating, as used at La Pasiega and Ardales, confirms these marks, geometric designs, dots and animals. These revealing advanced behaviors as pigment mixing, light planning, a mind attuned to stone’s story (Hoffmann et al., 2018). Neanderthals where not inferior to Sapiens, as evidences from many studies are revealing. These caves hold a silent testament to creativity, a bridge across species and eras.

Across the Globe

Much farther east, half planet away, Sulawesi, Indonesia, offers another ancient example. A cave painting of human-animal hybrids and a wild pig, dated to at least 51,200 years ago. Also dated with innovative uranium-based methods, it captures early storytelling, its figures dancing between worlds, a visual poem of connection (Aubert et al., 2019). These marks, like Atlantic carvings, endure as fragile threads, linking us to hands long vanished, their quiet intent etched into stone beneath time’s unyielding gaze.

Standing as echoes in stone, and to the likeness of its universal counterparts, the Atlantic rock art’s quiet lines resonate beyond open fields, intertwining with the shadowed chambers of megalithic tombs. A dialogue Richard Bradley for instance, traces with delicate precision. In Britain and Ireland, cup marks, spirals, and curvilinear motifs on passage graves like those in the Boyne Valley echo the open-air carvings. Their shared roots stretching to the mid-fourth millennium BC. Bradley notes O’Sullivan’s “Depictive Style”, shallow, pecked lines scattered haphazardly across stones at Newgrange, Knowth, and Dowth, predating the tombs’ final form, around 3100–3000 BC (O’Sullivan, 1986, 1989). These simple marks, akin to open-air designs, suggest an earlier origin, a primal urge to mark stone before architecture confined it.

Distinctions

Yet differences can be seen in the stone’s grain. Open-air carvings, unlike the sculpted “Plastic Style” of later tomb art, rarely mold to rock contours, their technique closer to Boyne’s deeper, in-situ carvings but lacking their formality (Shee Twohig, 1981). In Galicia and France, the overlap thins, for cup marks appear, but circles and animals diverge, rooted in distinct traditions. At Clava in Scotland, passage graves reuse cup-marked slabs, their motifs mirroring local landscapes, a bridge to Ireland’s portal dolmens dated to the early fourth millennium BC (Bradley, 1993).

These echoes, both shared and distinct, hint at a cultural web stretching across Atlantic shores, a Neolithic pulse where stone spoke to stone, yet diverged in voice. Bradley’s inquiry invites us to listen, not just to the marks, but to the hands that carved them, their stories layered beneath time’s weight, a fragile harmony we strain to hear.

Assesment

In the end, what we do know, is that we now see a long arc of use followed by an abrupt fade to oblivion. As we have seen, Atlantic rock art’s story stretches across millennia, a slow cadence of creation and silence. Although I do not support this dates, what we are told is that the Atlantic rock art was born in the Late Neolithic, around 3300 BC, its abstract motifs, cups, rings and spirals, endured into the Early Bronze Age, capturing daggers and halberds of the Beaker horizon, circa 2500–2000 BC (Bradley, 1993). In Britain, sites like Ilkley Moor, with Late Neolithic flintwork dated 2900–2600 BC, and Galicia’s Lombo da Costa, with copper axes, hum with a long life, their carvings a testament to continuity (Edwards and Bradley, in press; Monteagudo, 1977).

Yet, this vitality waned as landscapes shifted. By the Late Bronze Age or Iron Age, rock art’s voice quieted, buried beneath new purposes. On Ilkley Moor, field walls overlay carvings; at Dod Law in Northumberland, a hillfort’s rampart entombed a decorated surface (Ilkley Archaeology Group, 1986; Smith, 1989). In Galicia, early hillforts similarly smothered petroglyphs, their metalwork depictions fading from use by the Middle Bronze Age (García and Peña, 1980). Eston Nab in Cleveland saw cup-marked boulders reused as packing in palisaded enclosures, their original meaning obscured (Vyner, 1988a).

Interpretations

Bradley’s chronicle paints a landscape transformed, where art once vibrant yielded to plough and fortification. These stones, once alive with meaning, now lie silent, their long arc a poignant reminder of cultures adapting, then letting go, a whispered elegy for a past etched, then erased, beneath time’s unyielding tread.

But is it really so. Should we take this discourse as gospel? Would a community, a culture so interconnected, interdependent with Nature and the Cosmos, really change in such short times? Or could it be that in most cases, what did happened was either a natural catastrophe or the fruit of merciless invasion by other cultures that had no knowledge or respect for others cultures, one caring only for the resources of any given area? Is it not so today?

Are not cultures in existence that believe their faith allows them to deny a destroy any other? As for a catastrophe, it is well documented now, though not widely accepted that around 4000BC a multiple ocean impact from a fragmented comet, perhaps survivors of the Younger Dryas event, that only fell 7 thousand years latter.

Who knows how many times these chunks passed by our planet and what impact these bright fast moving objects (considering the Stars) have had into our ancestors culture and beliefs.

A legacy

All we now have is a legacy carved in silence, a sentinel across time, marking the bridge between northern Britain’s moors and Galicia’s cliffs, linking distant shores in a shared obscurity. Richard Bradley sees it as a “unitary phenomenon,” its circular motifs and weapon drawings weaving a web of long-distance connections, idols from Portugal to Brittany, daggers echoing Britain and Ireland, rooted in the late fourth millennium BC (Bradley, 1993). These stones, spanning 3300 BC to the early second millennium BC, hold a legacy of hands that carved, then vanished, leaving only their traces beneath hillforts and fields.

So I ask you dear reader, what stories linger in these weathered lines? Can you imagine the Neolithic artisans, their tools shaping stone under under Sun and Star, marking a world now lost, a world of portals and passage graves, of Beaker metals and fading rituals. With all we do not know, these symbolic representations that reach us from the remote years of our presence in this planet, are but a direct invite to listen to what they have to say. The problem is, we no longer understand their language. Let us stand before these silent carvings, their stillness a poem of persistence, and wonder at the hands that shaped them. In their quiet depths, we glimpse not just a past, but a mirror of our own fleeting place in time, etched forever in stone’s enduring gaze.

Bibliography:

Abélanet, J. 1990. Les roches gravées nord catalanes. Perpignan: Centre de recherches et d’études Catalanes.

Aira Rodriguez, M., Saa Otero, P. and Taboada Castro, T. 1988. Estudios paleobotánicos y edafológicos en yaciaiemtos arqueológicos de Galicia. Santiago de Compostela: Xunta de Galicia.

Alberti, A.P. 1982. Xeografía de Galicia, tomo 1. Coruña: Sálvora.

Almagro Gorbea, Ma. J. 1973. Los ídolos del Bronce 1 hispánico. Madrid: Biblioteca Praehistorica Hispana.

Alonso Romero, F. 1995. La embarcación del petroglifo Laxe Auga dos Cebros

(Pedornes, Santa Maria de Oia, Pontevedra). Actas del Congreso Nacional de

Arqueología, Vigo, vol 2, 137–45.

Alvarez Nuñez, A. 1986. Los petroglifos de Fentáns (Cotobade). Pontevedra

Arqueologica 2, 97–125.

Con’t.

Alvarez Nuñez, A. and Souto Velasco, C. 1979. Nuevas insculturas en Campo Lameiro. Gallaecia 5, 17–61.

Anati, E. 1963. New petroglyphs at Derrynablaha, Co. Kerry, Ireland. Journal of the Cork

Historical and Archaeological Society 68, 1–15.

Anati, E. 1964. The rock carvings of ‘Pedra das Ferraduras’ at Fentáns, Pontevedra. In E.Ripoll Perelló (ed), Micelánea en homenaje al Abate Henri Breuil, 123–35. Barcelona: Instituto de Prehistoria y Arqueología.

Anati, E. 1968. Arte rupestre nelle regioni occidentali delle Peninsola Ibérica. Brescia: Archivi di Arti Preistorica.

Anati, E. 1976. Metodi di rivelamento e di analisis arte rupestre. Capo di Ponte: Studi Camuni.

Anati, E. 1993. Rock Art—The Primordial Language. Capo di Ponte: Studi Camuni.

Anati, E. 1994. Valcamonica Rock Art—A New History for Europe. Capo di Ponte:

Edizioni del Centro.