The question of what became of Alexander the Great’s body has haunted historians for nearly two millennia. His tomb, once one of the most visited shrines of the ancient Mediterranean, vanished from the historical record after late antiquity. In its place rose a swirl of legends, scholarly conjectures, and archaeological dead ends. Yet in recent years, a provocative and meticulously argued hypothesis has emerged from researcher Andrew Michael Chugg. He draws on textual evidence, archaeological anomalies, and a striking convergence of historical timelines.

Chugg proposes that the remains venerated today in Venice as those of St Mark the Evangelist may in fact belong to Alexander the Great. His case is not a flight of fancy but a structured argument. One grounded in documented events, ancient testimonies, and physical artifacts. When the pieces are assembled, they form a narrative as bold as it is unsettling. The greatest conqueror of the ancient world may lie beneath the high altar of the Basilica di San Marco.

The Disappearance of Alexander’s Tomb

Alexander’s body was originally interred in Memphis, Egypt, before being transferred to Alexandria by Ptolemy II Philadelphus. Ancient writers including Pausanias, Strabo, and Diodorus Siculus confirm that the tomb (known as the Soma) became a centerpiece of the Ptolemaic capital. Roman emperors visited it, paid homage, and in some cases disturbed it. Augustus famously viewed the body and reportedly broke its nose while touching it. Caligula removed Alexander’s breastplate. Caracalla draped his own cloak over the corpse. These accounts demonstrate that Alexander’s mummy was not only real but publicly accessible well into the Roman period.

The last known reference to the body appears in the writings of Libanius around AD 390, who notes that Alexander’s corpse was still on display in Alexandria. After this, the record falls silent. The disappearance coincides with a seismic shift in the religious landscape: the Theodosian decrees outlawing pagan worship. Temples were shuttered, cults suppressed, and relics of deified figures, Alexander included, became politically dangerous. Alexandria, whose civic identity was tied to its founder, faced a dilemma. What does a Christianizing city do with the preserved body of a man officially declared a god by the Roman Senate?

Chugg argues that the solution was not destruction but repurposing. If Alexander’s body could no longer be honored as that of a pagan hero, it could be rebranded as that of a Christian saint. And remarkably, the first appearance of a supposed tomb of St Mark in Alexandria occurs at precisely this moment in history.

The Sudden Appearance of St Mark’s Tomb

Early Christian martyrdom traditions agree that Mark’s death in Alexandria was violent. The earliest accounts describe the mob dragging him through the streets until his body was torn and battered. Later versions add an attempted burning, halted by a sudden storm. However brutal the treatment, none of these texts preserve any memory of a tomb. For more than three centuries there is no mention of a burial site.

Then, in the late fourth century, everything changes. In AD 391–392, the emperor Theodosius outlawed pagan worship across the empire. Temples were closed, cults suppressed, and the religious landscape of Alexandria was forcibly rewritten. This created a unique problem for the city: Alexander the Great (a pagan and the city’s founder) had been venerated for centuries as a divine figure. His embalmed body, still on display in Alexandria as late as the 380s, suddenly became a political and theological liability.

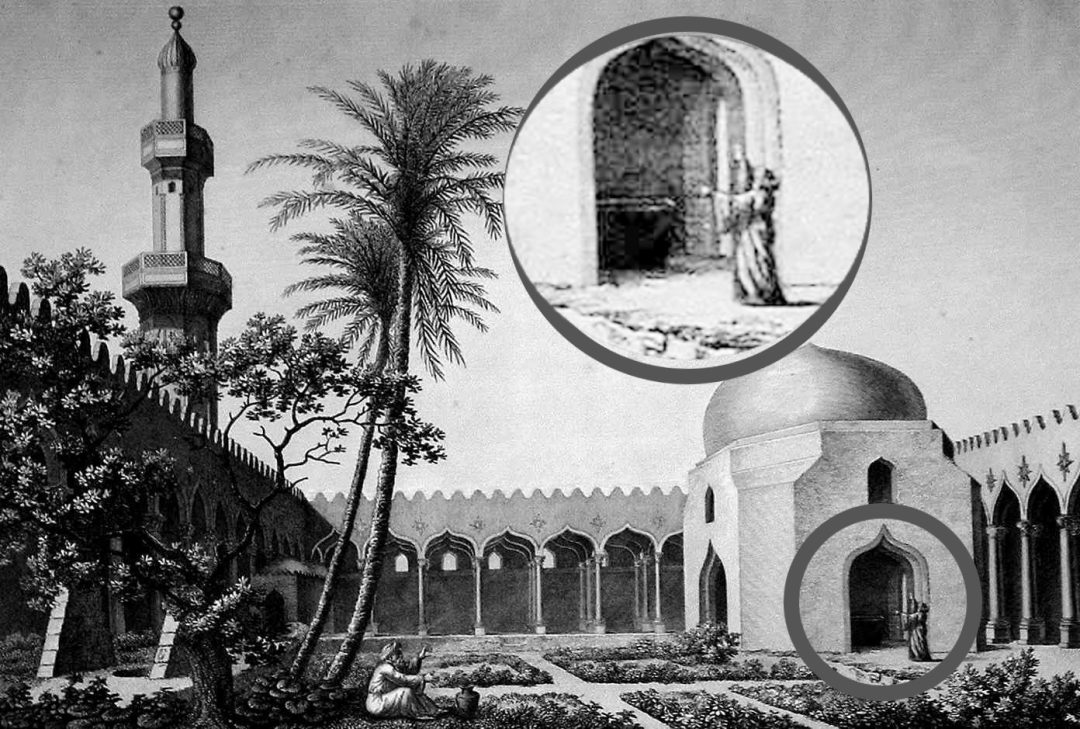

It is precisely at this moment that St Jerome, De viris illustribus in AD 392, states for the first time that Mark was buried in Alexandria. Within a few decades, pilgrims report visiting a church containing Mark’s tomb near the eastern gate. One in the very same district where ancient testimonies place Alexander’s Soma. The overlap is extraordinary. The disappearance of Alexander’s body from the historical record and the sudden appearance of Mark’s tomb occur in the same decade, in the same city, in the same location, under the same ideological pressure.

This is the foundation of Chugg’s thesis. But the argument does not rest on textual parallels alone.

The Venetian Translation and a Mysterious Body

In AD 828, two Venetian merchants, Tribunus and Rusticus, removed what they believed to be the body of St Mark from Alexandria and smuggled it to Venice. The event, known as the Translazione, is celebrated in Venetian chronicles and depicted in 12th‑century mosaics inside the Basilica di San Marco. Independent accounts from Christian pilgrims confirm that a body was indeed taken.

But the earliest traditions describe Mark’s corpse as mutilated and nearly burned, and no burial site was remembered for more than three centuries. Only after Theodosius’ decree does a tomb suddenly appear. So, what body did the Venetians actually remove?

Chugg suggests that the Alexandrians, needing to eliminate the public cult of Alexander without provoking unrest, rebranded his mummy as that of St Mark in the late fourth century and preserved it in a shrine near the eastern gate. When the Venetians arrived centuries later, they unknowingly carried off the remains of the Macedonian king.

By Andrew Chugg

Supporting this possibility is a remarkable artifact discovered in 1960 beneath the apse of the Basilica di San Marco. A sculpted limestone block bearing a Macedonian starburst, the emblem of Alexander’s dynasty. Archaeologist Eugenio Polito identified it as part of a high‑status Hellenistic tomb. Its casing dating to the third or early second century BC. Its presence in Venice, mere meters from the alleged tomb of St Mark, is difficult to explain unless it was brought from Alexandria along with the body.

The Nectanebo II Sarcophagus and the Outer Casing

Another pillar of Chugg’s argument involves the sarcophagus of Nectanebo II, the last native pharaoh of Egypt. This sarcophagus, discovered in Alexandria by Napoleon’s forces in 1798 and now housed in the British Museum. It was never used by Nectanebo, who fled Egypt before his death. Ancient sources state that Ptolemy I buried Alexander in Memphis.The availability of an unused royal sarcophagus fits the timeline perfectly. In 1801 the British captured Alexandria from the French and were told that the Nectanebo II sarcophagus had been Alexander’s tomb by the local inhabitants.

Authors note: This line of reasoning fits the conventions of the period. It was not uncommon sarcophagi meant or used for one were repurposed for another.

Chugg demonstrates that the Venetian star‑shield block fragment, when extrapolated, matches the dimensions of the Nectanebo sarcophagus with uncanny precision, suggesting it once formed part of an outer casing built around Alexander’s tomb.

The British Museum itself has recently softened its stance on the sarcophagus, revising its description to acknowledge that it was historically believed to be associated with Alexander.

A Case That Demands Investigation

Chugg’s thesis does not claim certainty, but it presents a coherent, evidence‑based scenario. One that resolves multiple historical puzzles:

- Disappearance of Alexander’s tomb.

- Sudden invention of St Mark’s burial site.

- Presence of Macedonian funerary art in Venice.

- Survival of a mummified body despite early Christian accounts of Mark’s cremation.

The final step? Examining the bones beneath the high altar of San Marco. But this has not been permitted since the early 19th century. Yet such an examination could answer the question definitively. Alexander suffered well‑documented injuries, including a chest wound at the Mallian town and a leg wound in Sogdiana. These would leave unmistakable traces on skeletal remains. If the body in Venice bears these marks, the implications would be extraordinary.

Chugg himself comments: “The perished mummy in the Basilica di San Marco deserves a resolution of the enigma of its identity and history needs to tell its true story.”