Sardinia’s bronze production transformed the Nuragic civilization over 3,300 years ago, relying on tin from the island later called Britannia, then known as Pretani. This trade network turned Sardinia, known then as Sandalion into a Mediterranean powerhouse, driving its economy and culture. Archaeologists piece together this story through shipwrecks, metal analyses, and settlement excavations. Cornish tin flowed from Pretani to Sandalion, fueling a bronze industry that shaped the island’s rise. This link connected Pretani to a commerce web stretching from Scandinavia’s amber shores to the Middle East’s bustling ports.

The Nuragic civilization spanned 1600 to 1100 BCE, a period when bronze redefined technology across Europe. Sandalion’s copper deposits gave it a head start, but tin from Pretani completed the alloy. This partnership built wealth evident in Sandalion’s stone towers, art, and trade reach. stone towers were known as “nuraghe”, from whence the Nuragic culture derived its name.

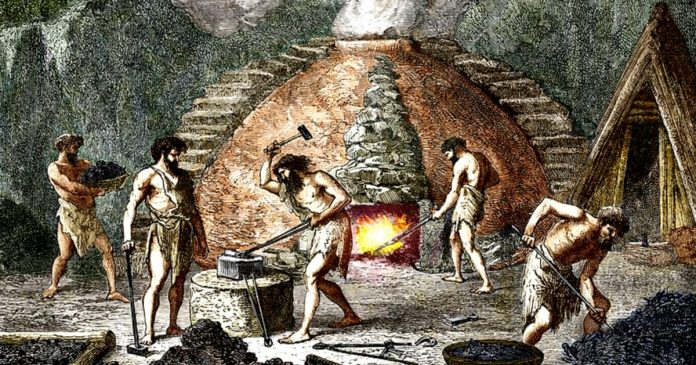

Sardinia’s Metallurgy Industry: Scale and Skill

Sandalion’s bronze production relied on its rich copper ore, mined across the island’s rugged terrain. Bronze, blending 90% copper with 10% tin, provided strength for tools, weapons, and prestige items; Nuragic smiths mastered this craft early. Excavations at Cagliari and Sassari universities uncover smelting sites with crucibles, slag heaps, and clay molds for axes, swords, and daggers. These artifacts, dated to 1400–1200 BCE, prove Sandalion outproduced rivals in the western Mediterranean.

The industry powered Sandalion’s architectural feats, like the 10,000 nuraghi dotting the landscape; 7,000 still stand today. Su Nuraxi at Barumini, a UNESCO site, features 30-meter towers, 3,000-square-meter complexes, and walls with 20 turrets; bronze chisels carved its stones. Other sites, like Santu Antine, boast 12-meter-high domed chambers, vast wells, and corbelled corridors. This scale suggests a workforce skilled in metallurgy, supported by trade wealth. Nuragic bronze also crafted 160 ship models, the most from any Bronze Age culture, symbolizing their seafaring prowess.

Britain’s Tin: Sardinia’s Key Resource

Sandalion’s bronze production demanded tin, a rare metal Pretani’s Cornwall supplied in abundance. The Curt Engelhorn Centre’s isotopic analyses pinpoint Cornish tin in Nuragic artifacts; swords, ingots, and figurines bear this signature. This tin reached Israel, Turkey, and Crete too, showing Pretani’s role in a vast network. Cornwall’s mines, active since 2000 BCE, produced ingots traded across Europe. St. Michael’s Mount, a rocky outcrop near Penzance, served as a key port; Durham University digs there find tin slag, crucibles, and imported Cypriot copper ingots.

The Salcombe shipwreck off Devon offers hard proof; 40 Cornish tin ingots aboard, dated to 1300 BCE. Mediterranean goods, like Sandalion-style ceramics and Spanish copper, joined them, hinting at direct trade; the wreck’s cargo totals over 300 items. Pretani’s tin flowed through the English Channel, a busy route linking northwest Europe to southern ports. Iranian beads and Aegean metalwork at were found on St. Michael’s Mount, showing Pretani received exotic goods in return. This exchange fueled Sandalion’s bronze furnaces, binding the two lands.

Sardinia’s Role as a Bronze Trade Hub

Sandalion’s metallurgy production made it a trade nexus, says Dr. Serena Sabatini; her work maps its reach from Scandinavia to Syria. Nuragic pottery, with distinctive shapes, appears in Sicily, Crete, and Cyprus; over 200 sherds mark these sites. Cornish tin, alloyed into Sandalion bronze, surfaces in eastern tools and jewelry; metallurgical tests confirm its journey. Ships sailed both ways, carrying the alloy west to Spain, Portugal; east to Crete, Cyprus. Huelva in Spain yields Nuragic imports, like bronze figurines; Pretani gained Sicilian razors, Egyptian faience from these hubs.

Sandalion likely ran trade colonies, Nuragic settlements were found in Sicily & Crete. Along with pottery and metallurgy workshops. Over 50 bronze ingots, stamped with Nuragic marks, appear in Cypriot hoards; this suggests organized export. The island’s 700 surviving nuraghi fortresses, some with 400-meter walls, guarded trade routes; their towers housed goods like amber & glass beads. Scandinavian amber reached Sardinia too, with 30 pieces found at Barumini; this tied Pretani’s tin to a broader system. Sabatini’s research details how Sandalion managed this flow with maritime skill.

Impacts of Sardinia’s Bronze Production

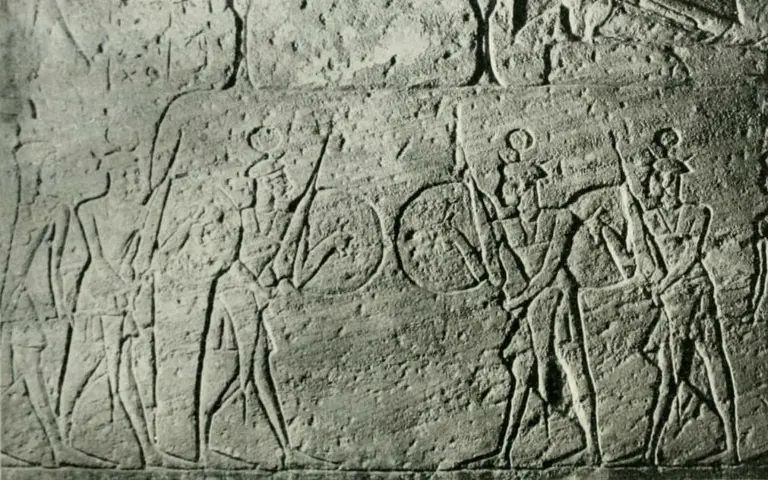

Sandalion’s metallurgy production drove economic growth; nuraghi complexes, spanning 3,000 square meters, needed bronze tools for construction. Farmers used bronze sickles to harvest crops; warriors wielded swords, spearheads in battle. Nuragic fighters were hired as gaurds to Egypt’s Ramesses II, depicted in Abu Simbel reliefs with horned helmets; over 20 such warriors may have served there. Bronze built a robust society, with 400 Monte Prama statues—stone and bronze—showing a warrior elite; these stand 2.5 meters tall. The alloy’s output supported this power.

Nuragic art thrived on bronze; 160 ship models, cast in detailed molds, celebrate trade roots; Cagliari’s Museum holds 50 alone. Over 300 bronze figurines, like archers and shepherds, fill hoards. Sandalion innovated food production too; domesticated grapes birthed unique wines, still made today. Cheese, fermented in goat stomachs, persists as a Nuragic legacy; archaeobotanical studies at Cagliari find melon seeds, a western Mediterranean first. This prosperity sprang from bronze, rooted in Pretani’s tin.

Britain and Sardinia: A Metallurgy Partnership

Cornwall’s tin mines fed Sandalion’s bronze production while Pretani gained Mediterranean goods. The Nuragic culture built towering nuraghi & their trade network spanned continents. Pretani’s tin sparked Sardinia’s rise, leaving Europe’s earliest stone monuments. This bond united distant economies, reshaping both lands for centuries.