A new open-access study in Scientific Reports has used synchrotron-based infrared spectroscopy to reconstruct the colour technology behind one of Iran’s most iconic archaeological finds: the naturally mummified “Salt Man No. 1” from the Chehrabad salt mine in north-western Iran.

By probing microscopic samples from his patterned wool trousers, researchers have identified the exact natural dyes, their likely botanical and insect origins, and how they interacted with the wool at a molecular level. The work not only reveals Sassanid dye recipes but also hints at trade routes and advanced craft knowledge in 3rd–4th-century Persia.

A 1,700-year-old wardrobe in a salt mine

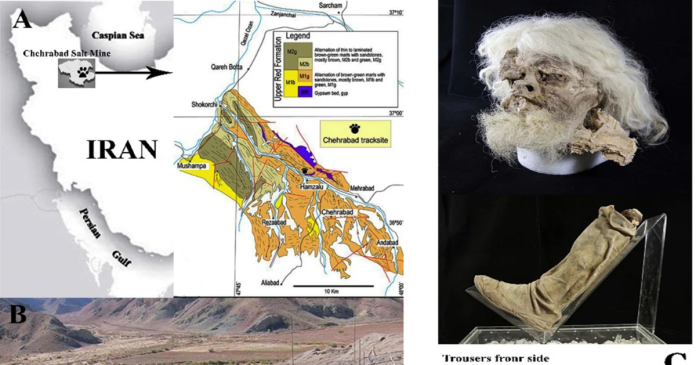

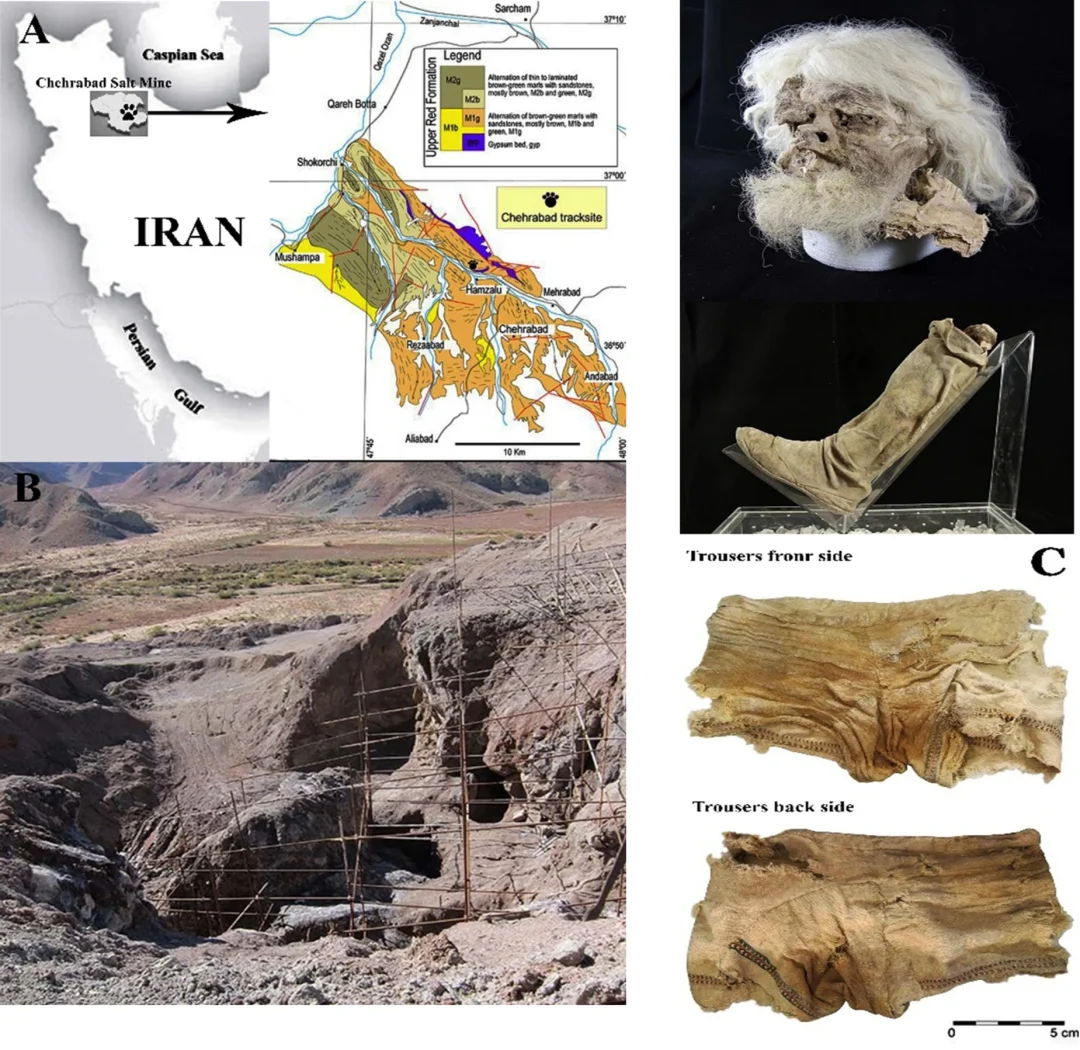

Chehrabad, in Zanjan Province, is famous for its “Salt Men” — miners whose bodies, clothes and even stomach contents were preserved by the highly saline environment. Salt Man No. 1, discovered in the 1990s, dates to between 220 and 390 A.D., firmly within the Sassanid period.

His remains include:

- Woollen half-trousers with colourful woven patterns

- A high leather boot

- Jewellery, including a gold earring

The quality of the textiles and accessories suggests he belonged to a higher social class, not an ordinary labourer. His trousers, in particular, have long attracted attention for their complex patterning and vivid colours — colours that are still visible after more than 1,700 years underground.

Why synchrotron FTIR matters

Traditional methods for identifying dyes (such as HPLC-MS) usually require cutting off relatively large fragments of textile — something conservators understandably try to avoid with unique artifacts like the Chehrabad trousers.

In this study, the team turned to synchrotron-based Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) microspectroscopy at the SESAME synchrotron facility in Jordan. Synchrotron light provides:

- Extremely bright, stable infrared radiation

- The ability to analyse individual wool fibres only tens of microns across

- Non-destructive or minimally invasive sampling

They combined FTIR with:

- Laboratory reference wool samples dyed using historical recipes (madder, cochineal, indigo, weld, walnut)

- Second-derivative and curve-fitting analysis of key spectral bands

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the lipid region of the wool spectra

This multi-layered approach allowed them to distinguish the dye molecules from the underlying wool protein and lipids with high confidence.

What colours did the Sassanid dyers use?

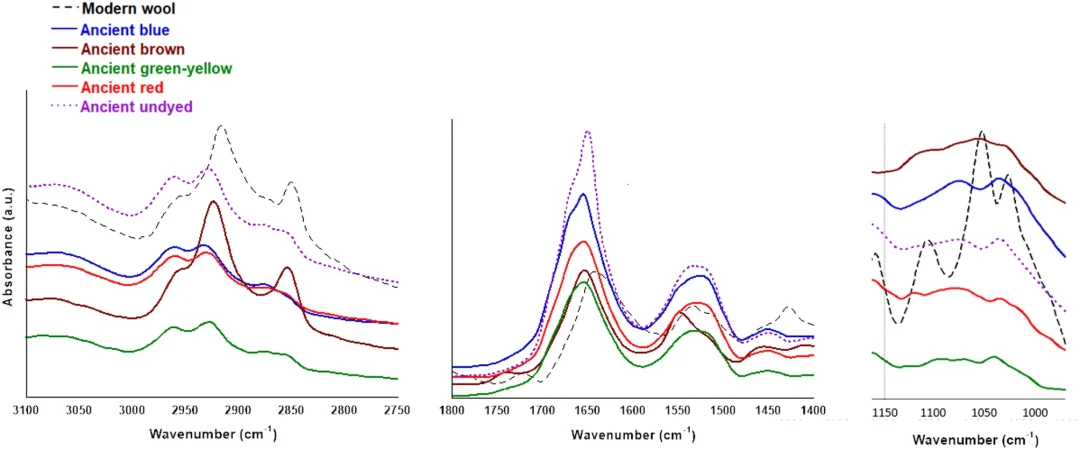

The trousers were woven in several colours — blue, red, yellow, brown and undyed areas. The FTIR signatures, compared with modern reference dyes, reveal the following palette:

Blue: Indigotin (vat dye)

- Spectral matches show that the blue fibres are coloured with indigotin, the main chromophore of indigo-type dyes (Indigofera spp.).

- The FTIR data, including characteristic bands around 1035 and 1075 cm⁻¹, point to vat dyeing — a reduction–oxidation process that drives the dye deep into the fibre.

Red: Madder and cochineal together

- The red threads show features of both alizarin (from madder, Rubia tinctorum) and carminic acid (from cochineal insects, Dactylopius coccus).

- This is particularly striking: cochineal has rarely been identified in textiles from this site, implying long-distance trade in high-status dyestuffs, or at least circulation of insect-based reds into Sassanid workshops.

Yellow: Quercetin and apigenin — but no luteolin

- Yellow fibres contained flavonoids quercetin and apigenin.

- Surprisingly, luteolin — usually dominant in weld (Reseda luteola), a classic Old World yellow — was absent.

- This suggests that Sassanid dyers at Chehrabad may have relied on alternative local yellow plants rather than standard weld recipes.

Brown: Tannic acid from walnut, without juglone

- The brown colour is linked to tannic acid, likely from Persian walnut (Juglans regia), a well-known traditional source of brown dyes.

- Juglone, another walnut pigment, was not detected, indicating a selective extraction or particular processing method focused on tannins rather than the full pigment spectrum.

The authors note that this is the first time tannic acid has been identified in this context, and that carminic acid has not previously been reported in other red textiles from the Chehrabad mine — both important “firsts” for the site and period.

Reading dye recipes from wool proteins and lipids

The study goes beyond “what colour was used” and asks “what did these dyes do to the wool itself?”

Wool’s structure is dominated by:

- Keratin proteins (mechanical strength, elasticity; main dye-binding sites)

- Lipids (waxy components forming a hydrophobic barrier around fibres)

Keratin: subtle structural changes

In the amide bands (linked to protein secondary structure), the team used second derivatives and curve fitting to decompose broad peaks into contributions from α-helices, β-sheets, turns and random coils. They observed:

- Vat-dyed indigo samples showing increased β-sheet content, consistent with some rearrangement of the keratin structure.

- Mordant-dyed reds and yellows (madder, cochineal, flavonoids) causing mixed modifications to protein conformation.

- Tannin-dyed wool remaining closest to the undyed reference in its protein architecture.

Overall, however, the core keratin structure of the Chehrabad textiles appears well preserved, reflecting both the intrinsic durability of wool and the stabilising influence of the salty burial environment.

Lipids: the key to dye uptake

The most striking differences emerged in the lipid region (3050–2800 cm⁻¹), which captures CH₂ and CH₃ stretching in fatty chains. PCA on this region effectively grouped the samples by dyeing method:

- Vat-dyed indigo fibres clustered separately, indicating substantial modification of the epicuticle lipids during reduction and re-oxidation.

- Mordant-dyed reds and yellows formed a distinct cluster, showing similar lipid disruption patterns due to metal–dye–fibre complexes.

- Tannin-dyed brown fibres sat close to undyed wool, suggesting that walnut tannins bonded without significantly reorganising the lipid barrier.

- Modern undyed wool used as a control occupied its own space in the plot, reflecting different preparation methods from ancient textiles.

Loadings on the principal components point to shifts in lipid saturation and chain packing — essentially, the way dye processes “fluidise” or stabilise the outer lipid layer of wool, which in turn affects dye penetration and fastness.

What this tells us about Sassanid Persia

Taken together, the findings paint a picture of a sophisticated textile industry in Sassanid Iran:

- Technological know-how

- Mastery of different dye technologies: vat dyeing for blues, mordant dyeing for reds and yellows, and tannin-based browns applied directly.

- Ability to control dye–fibre interactions without destroying wool structure, preserving both colour and fabric integrity.

- Trade and connectivity

- Presence of cochineal suggests access to high-value insect dyes, pointing to far-reaching exchange networks or imported dyestuff traditions.

- The unusual yellow signature (apigenin and quercetin without luteolin) hints at regional plant traditions, possibly distinct from Roman and Byzantine recipes.

- Cultural identity

- The Salt Man’s trousers, with their bright, chemically complex palette, reinforce the reputation of Sassanid textiles as prestige goods in Late Antique global trade.

Where the Findings Lead Us

The authors emphasise that this work is part of an ongoing project. Future steps include:

- Building a reference library of native Iranian yellow dye plants to resolve the apigenin–quercetin puzzle.

- Expanding sampling to more textiles from Chehrabad and other Sassanid sites.

- Testing the emerging link between dyeing methods and lipid signatures across a broader range of archaeological and experimental fibres.

For historians and archaeologists, the study shows how synchrotron FTIR can unlock detailed technological stories from microscopic fragments of cloth — without sacrificing the artifacts themselves. For those interested in ancient colour, it confirms what the Salt Man’s trousers have been hinting at for decades: Sassanid Persia was not only politically powerful, but also a centre of chemical and artistic innovation in textile dyeing.