The ancient Garamantes civilization, a sophisticated society that thrived in the Sahara Desert, was revealed through groundbreaking satellite imagery studies in southwestern Libya’s Fezzan region. This remarkable discovery, made by researchers from the University of Leicester, has unveiled over 100 fortified farms, villages, and towns with castle-like structures, reshaping our understanding of this once-mischaracterized culture. Dating primarily between AD 1 and 500, these settlements demonstrate the Garamantes’ advanced urban planning, irrigation systems, and role in trans-Saharan trade. This article explores the discovery, the civilization’s achievements, and the methods that brought this hidden history to light.

Discovery Through Satellite Imagery

In 2011, a team led by Professor David Mattingly from the University of Leicester utilized high-resolution satellite imagery and aerial photographs to identify over 100 fortified settlements in the Fezzan region. The project, funded by the European Research Council, the Leverhulme Trust, the Society for Libyan Studies, and the GeoEye Foundation, capitalized on technological advancements to uncover sites previously obscured by the desert’s harsh terrain. The fall of the Gaddafi regime in 2011 lifted restrictions on archaeological exploration of Libya’s pre-Islamic heritage, enabling this research.

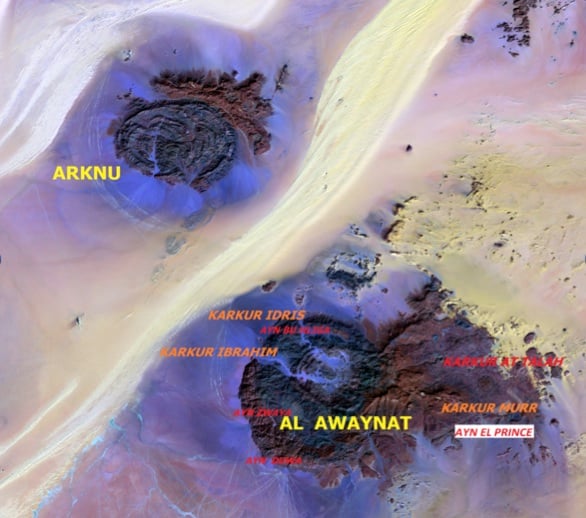

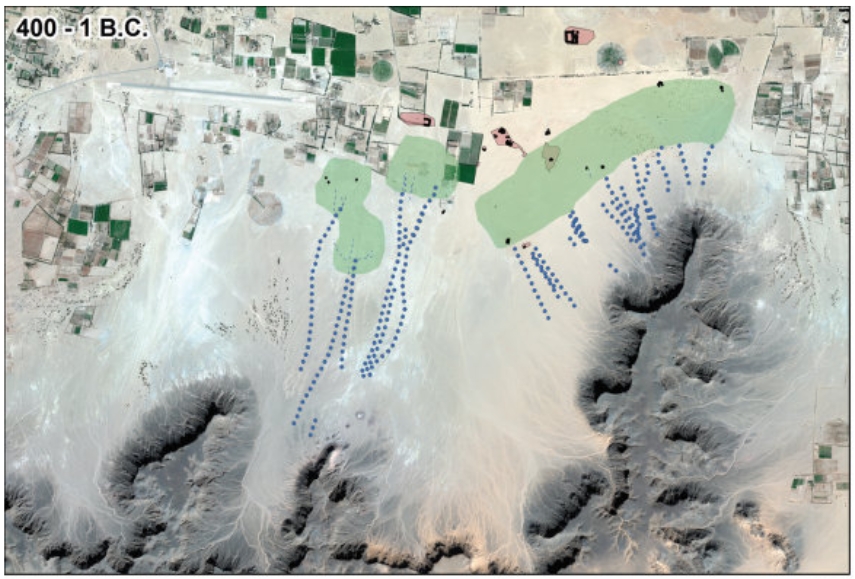

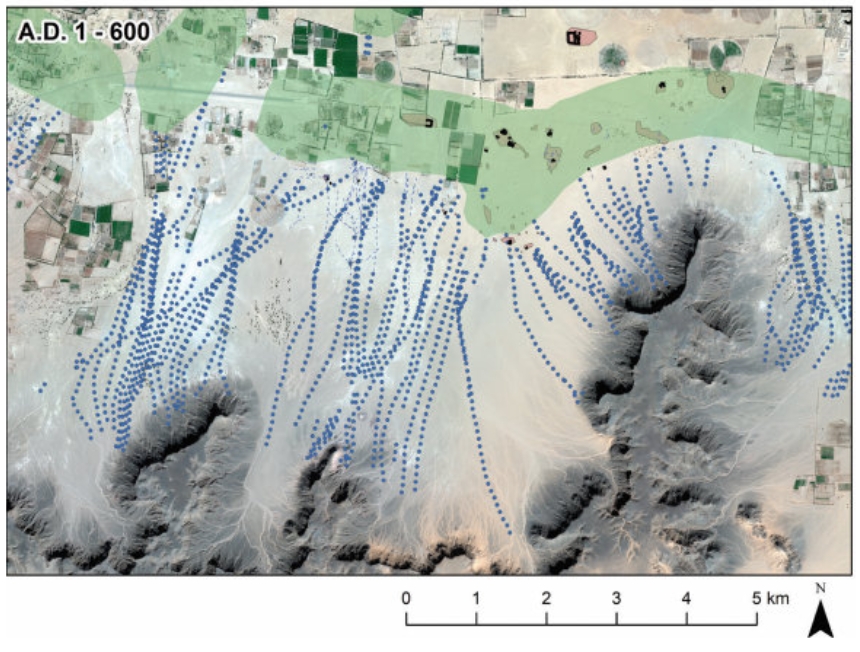

The team analyzed images from commercial satellites and oil industry surveys, supplemented by aerial photographs from the 1950s and 1960s. These tools revealed a dense network of settlements, including the Garamantes’ capital, Garama (modern-day Jarma), and other sites like Al Awaynat (oasis). Fieldwork confirmed the findings, with Garamantian pottery and mudbrick structures providing tangible evidence of the civilization’s existence. The settlements, some featuring walls up to four meters high, included farms, villages, towns, cairn cemeteries, wells, and agricultural fields, indicating a highly organized society.

The Garamantes Civilization: A Sahara Oasis Culture

The Garamantes civilization, centered in the Wadi al-Ajal valley, defied the Sahara’s arid conditions through innovative irrigation systems. They constructed underground channels called foggaras or qanats, which tapped into fossil water aquifers to sustain agriculture. These systems supported oasis farming, allowing the cultivation of crops in an otherwise inhospitable environment. The settlements’ layouts, with fortified structures and interconnected field systems, suggest a complex society capable of supporting a significant population.

The Garamantes were not the nomadic barbarians described by ancient Greek and Roman sources like Herodotus and Pliny. Instead, they developed a state with urban centers, a written language, metallurgy, and high-quality textile production. Their capital, Garama, featured large-scale mudbrick architecture, including castle-like buildings that likely served defensive and administrative purposes. Archaeological evidence also points to a robust economy driven by trans-Saharan trade, with the Garamantes acting as intermediaries between sub-Saharan Africa and the Mediterranean world. Goods such as gold, ivory, and slaves likely passed through their networks, connecting them to Roman markets.

The discovery of over 100 sites, including at least ten village-sized settlements within a 1.5-square-mile area, underscores the civilization’s scale. This density rivals that of other ancient urban societies, challenging earlier assumptions about the Sahara’s historical inhabitants. The Garamantes’ ability to thrive in such a challenging environment highlights their engineering prowess and cultural sophistication.

Methods and Challenges of the Discovery

The use of satellite imagery marked a turning point in studying the Garamantes civilization. Traditional archaeological methods faced significant obstacles in the Sahara, including vast distances, extreme temperatures, and political restrictions under the Gaddafi regime. Satellite imagery allowed researchers to survey large areas efficiently, identifying subtle features like eroded walls and buried irrigation channels invisible from the ground. The 1950s and 1960s aerial photographs provided additional context, capturing the landscape before modern development altered it.

Fieldwork complemented the remote sensing data. Teams visited key sites to collect artifacts, such as pottery, and to map structures. These efforts confirmed the satellite findings and provided a timeline for the settlements, with most dating to the first five centuries AD. The combination of remote and on-the-ground methods proved essential in reconstructing the Garamantes’ world.

However, challenges persisted. The Sahara’s harsh conditions have eroded many structures, and looting has damaged some sites. Political instability in Libya since 2011 has also limited further exploration. Despite these hurdles, the project’s success demonstrates the power of integrating technology with traditional archaeology to uncover hidden histories.

Significance of the Garamantes Civilization

The discovery of the Garamantes civilization redefines our understanding of ancient North Africa. Far from being marginal nomads, the Garamantes built a state comparable to contemporary Mediterranean societies. Their irrigation systems, urban planning, and trade networks reveal a people who mastered their environment and played a pivotal role in connecting African regions. This challenges Eurocentric narratives that often downplayed pre-Islamic African civilizations.

The Garamantes’ decline, likely around the 7th century AD, coincided with the depletion of groundwater reserves and disruptions in trans-Saharan trade following the Roman Empire’s fall. These factors likely strained their agricultural and economic systems, leading to the abandonment of many settlements. Today, their mudbrick structures are eroded, but the satellite imagery discovery ensures their legacy endures.

Implications for Future Research

The findings open new avenues for studying the Garamantes civilization and other Sahara cultures. Satellite imagery has proven invaluable for identifying sites in remote regions, suggesting potential for similar discoveries elsewhere. The Fezzan region, with its rich archaeological record, remains a priority for researchers, though ongoing instability in Libya poses challenges. Future studies could focus on the Garamantes’ trade goods, social structure, and interactions with neighboring cultures to further illuminate their world.

The project also highlights the importance of interdisciplinary approaches. Combining archaeology, history, and technology allows researchers to piece together stories that might otherwise remain buried. As satellite imaging technology advances, more discoveries may emerge, offering fresh perspectives on ancient African civilizations.

Legacy of the Garamantes

The discovery of the Garamantes civilization through satellite imagery stands as a testament to human ingenuity, both ancient and modern. The Garamantes transformed the Sahara into a hub of agriculture and trade, leaving behind a network of fortified settlements that endured for centuries. Their story, uncovered through meticulous research and cutting-edge technology, corrects historical misrepresentations and celebrates their achievements.

This work also underscores the value of preserving archaeological sites. The Fezzan region’s harsh environment and human activities threaten these remnants, making documentation and protection critical. By studying the Garamantes, we gain a deeper appreciation for the diversity of ancient societies and their contributions to global history.

In conclusion, the uncovering of the Garamantes civilization in the Sahara Desert through satellite imagery reveals a sophisticated society that thrived against the odds. Over 100 fortified farms, villages, and towns, complete with advanced irrigation and urban systems, paint a picture of a people who mastered their environment. This discovery, made possible by the University of Leicester’s innovative approach, invites us to reconsider the history of the Sahara and the role of African civilizations in antiquity. As research continues, the Garamantes’ legacy will inspire further exploration into the rich tapestry of human history.