This Content Is Only For Subscribers!

A secret Mayan sign language has been hidden in plain sight. A groundbreaking discovery about Ancient Maya communication was published in a paper on February 21, 2025. The study explores how the Ancient Maya embedded hand forms in figural art to convey numerals. Particularly on Altar Q, an 8th-century sculptural text from Copán. Rich A. Sandoval proposes that these hand signs represent a unique script complementing hieroglyphic writing. He offers a fresh perspective on Maya textual traditions.

Unveiling a New Script in Ancient Maya Art

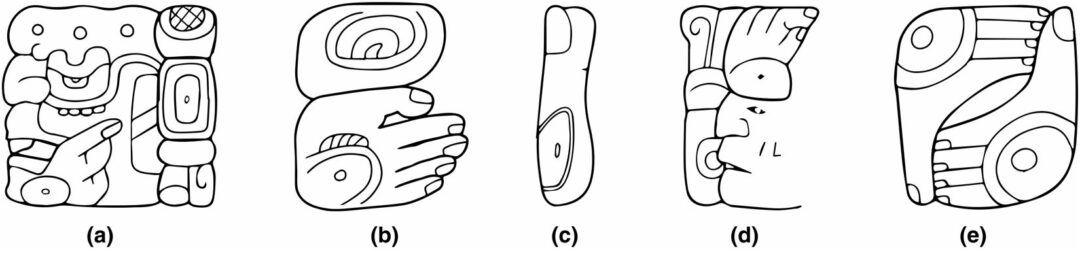

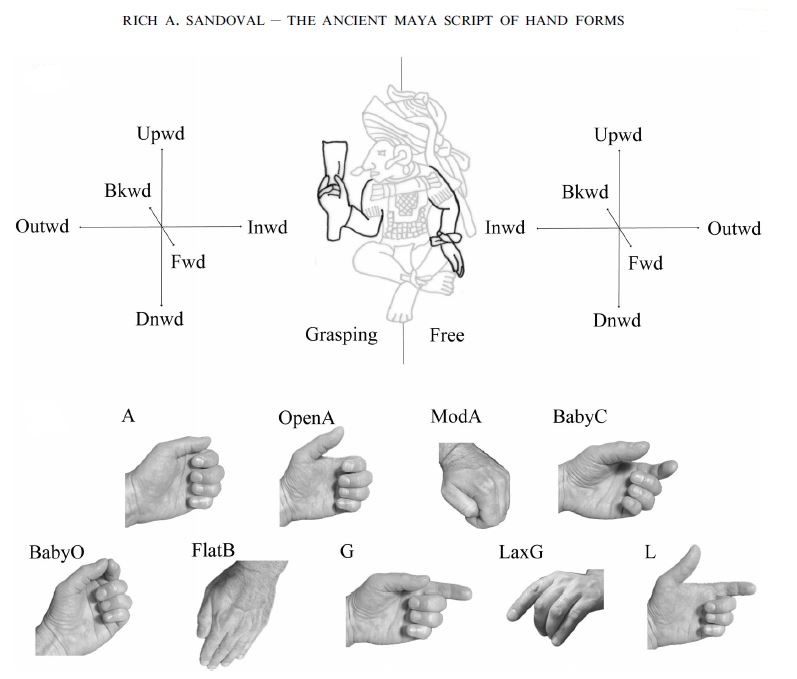

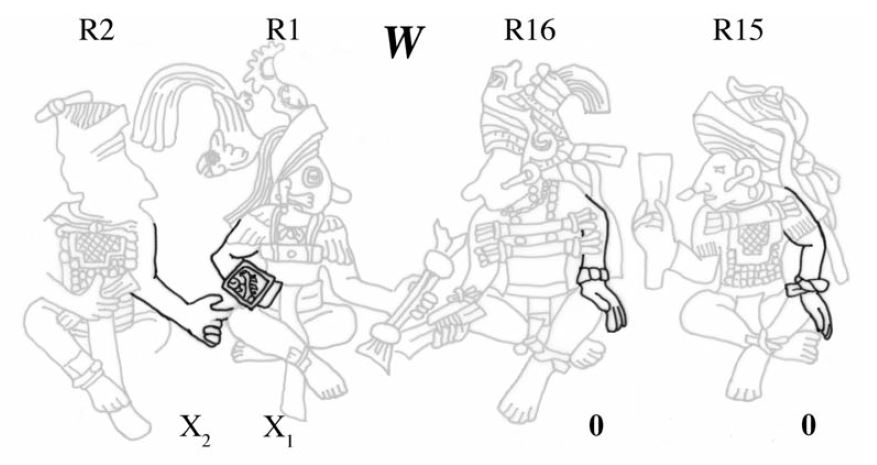

Sandoval’s research highlights that Ancient Maya texts rely heavily on hieroglyphic inscriptions for information, while figural art dominates visually with distinctly formed hands. These hands, often overlooked, suggest an iconographic embedding of hand signs that serve as a semantic expression alongside hieroglyphs. Despite previous efforts to decipher Maya hieroglyphs and iconography, the meaning of these hand forms remained elusive until now. Sandoval’s novel approach uses phonological parameters (handshape, orientation, and position) to define hand forms as graphic symbols. He focuses on Altar Q, which features 16 figural depictions of Copán’s rulers, providing a rich dataset for analysis due to its abundance of hand signs and extensive hieroglyphic context.

The paper argues that each hand sign on Altar Q encodes one of four Long Count dates. Verified through mathematical analysis of 11 unique numerical hand signs. This finding challenges the traditional view that hieroglyphs alone suffice for textual interpretation. It suggests a more complex multimodal system. Sandoval’s evidence includes isomorphisms between hand signs and hieroglyphs, intra-textual references, and direct links to hieroglyphic data. In doing so establishing a robust foundation for future decipherment efforts.

Methodology and Evidence from Altar Q

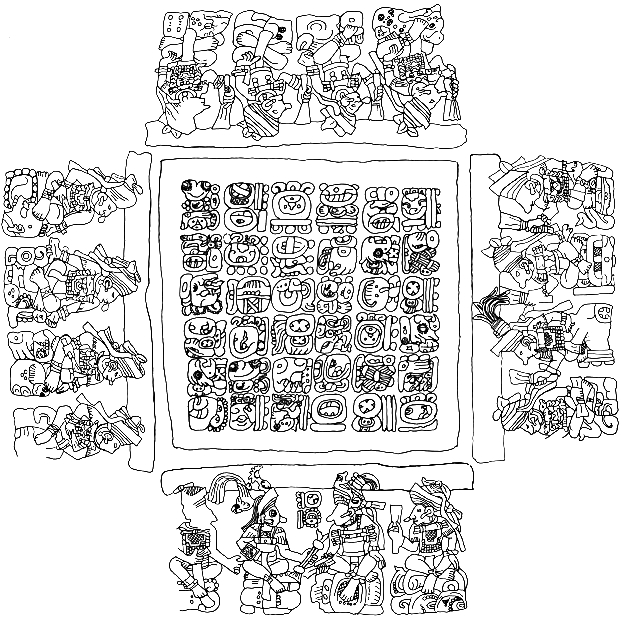

Altar Q, located in Copán’s West Court, serves as the cornerstone of Sandoval’s study due to its ideal characteristics. The monument, dating to the late 8th century, includes 36 hieroglyphic blocks and depictions of 16 rulers, each accompanied by varying hand forms. Sandoval eliminates variables like social status by focusing on dynastic rulers, controlling for static elements like heads and torsos, and leveraging the well-understood hieroglyphic context. This approach reveals abnormalities in the inscription, hinting at missing calendrical information that hand signs might supply.

hieroglyphic date on its West Panel, depictions of 16 rulers sitting on self-identifying

hieroglyphs, and many elements of iconographic symbolism and embedding. Note that

because the West Panel is positioned on the bottom, the topside hieroglyphic inscription is

upside down. (a) Photograph by author. (b) Drawing by author, following the interpretation

of Linda Schele’s illustration (see Schele & Freidel 1990: 310, fig. 8:3)

The evidence breaks into three thematic groups: isomorphisms, calendrical and directional references, and equations. Isomorphisms show that hand-sign patterns mirror hieroglyphic numerical sequences typical of Long Count dates, with some hand shapes matching hieroglyphic variants of zero. Calendrical references suggest that expected Long Count dates, absent from hieroglyphs, appear in hand signs, aligning with the 9th Bak’tun period. Equations highlight obscured distance numbers in the inscription, resolved by positing hand-sign-encoded dates. This multifaceted evidence, independently verified, supports Sandoval’s decipherment.

Historical Context and Previous Research

The study situates itself within a long history of Maya research, noting that distinctive hand forms appear across various text types, from sculptures to vases, since around 500 BCE. Earlier studies by scholars like Benson (1973) and Miller (1983) analyzed hand forms for social standing, while Mallery (1972) and Fox Tree (2009, 2016) explored connections to indigenous signed languages. However, these efforts lacked a systematic basis in Maya writing. Sandoval builds on this, integrating hieroglyphic analysis and modern gesture studies to propose a numerical hand-sign system, a concept previously unaddressed in Altar Q literature.

This innovation contrasts with known numerical systems, which typically use transparent finger counting. Sandoval’s esoteric hand signs, lacking a direct form-value relationship, align with rare signed-language subsystems and Maya emphasis on opaque hieroglyphic meanings. Ethnographic support from modern Maya gesture usage for time reckoning further bolsters this interpretation.

What the Secret Mayan Sign Language Reveals: Decoded Dates and Their Meanings

The secret Mayan sign language on Altar Q uncovers specific dates in the Ancient Maya Long Count calendar. This system counts days from a mythical start in 3114 BCE. Each date follows the format Bak’tun.K’atun.Tun.Winal.K’in. Bak’tuns span about 394 years. K’atuns cover 20 years. Tuns equal one year. Winals are 20 days. K’ins are single days.

| Unit | Days per Unit | Approximate Equivalent |

| Bak’tun | 144,000 | 394 years |

| K’atun | 7,200 | 20 years |

| Tun | 360 | 1 year |

| Winal | 20 | 20 days |

| K’in | 1 | 1 day |

Sandoval’s decipherment shows a hybrid approach. The Bak’tun value, always 9 here, comes from hieroglyphs on the panel rim and ruler heads. This 9 appears upside down to evoke the underworld. The lower units derive from hand signs of the four rulers per panel. Scribes read these left to right. This setup forms one full date per side.

East Panel: A Founder’s Death Date

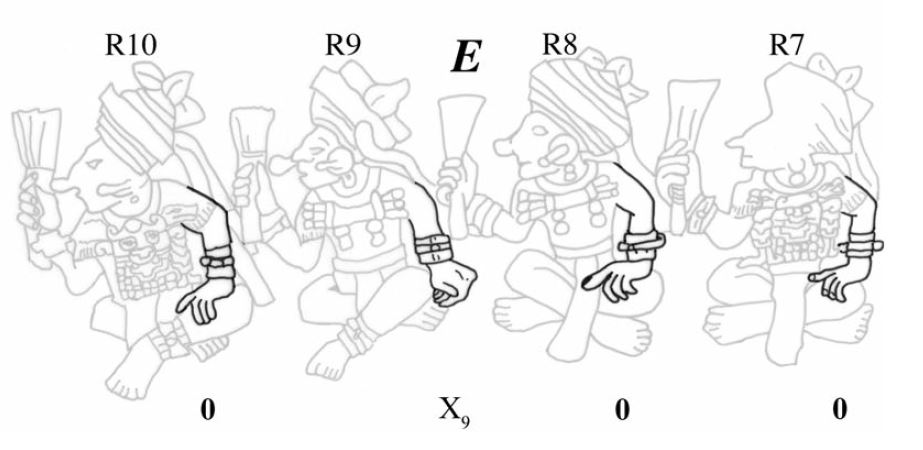

The East Panel reveals 9.0.2.0.0, or November 27, 437 AD. This marks Ruler 1’s death, the Copán dynasty founder. Hand signs encode 0 (K’atun), 2 (Tun), 0 (Winal), 0 (K’in). The 0s use a “LaxG” form with extended fingers and palm down. The 2 features an asymmetric two-handed pose. Verification comes from a distance number equation in the hieroglyphs. Adding 0.17.3.0.0 to this date yields 9.17.5.0.0, matching another implied date.

South Panel: A Ritual Event

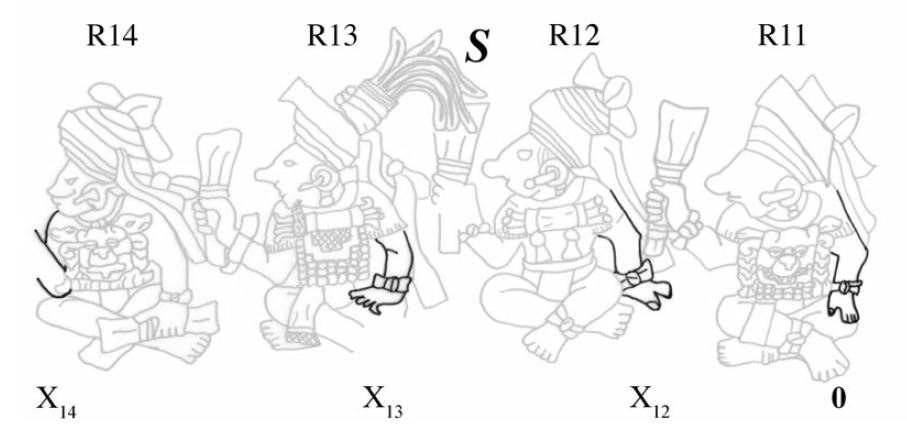

Here, the secret Mayan sign language decodes to 9.16.13.12.0, equating to October 21, 764 AD. It ties to a ritual, possibly a period-ending ceremony. Values include 16 (K’atun), 13 (Tun), 12 (Winal), 0 (K’in). The 16 appears as a raised free hand, unique to Ruler 14. The 13 and 12 use distinct asymmetric forms. The 0 employs a “FlatB” shape (a specific hand sign), flat hand with palm up. Math works by adding 0.17.3.1.0 from hieroglyph blocks with hand signs of 8.19.10.11.0 equaling 9.16.13.12.0.

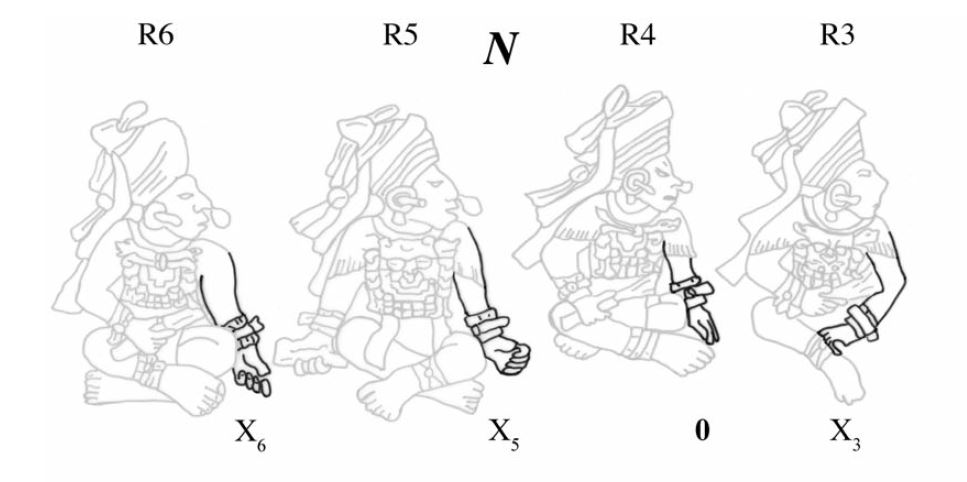

North Panel: Part of a 64-Day Ritual

The North Panel’s date is 9.17.5.0.15, January 7, 776 AD. This connects to a 64-day ritual sequence in Copán’s history. Hand signs give 17 (K’atun), 5 (Tun), 0 (Winal), 15 (K’in). The 5 and 15 show symmetric two-handed forms, near-identical in shape, placement, and orientation. These signal boundary numbers like 5, 10, 15. The 17 is asymmetric. The 0 is FlatB. Directional ties in the West Court support this as a northern reference.

West Panel: The Final Ruler’s Death

The West Panel yields 9.19.10.0.0, April 30, 820 AD. It signifies Ruler 16’s death, closing the dynasty. Encoded values: 19 (K’atun), 10 (Tun), 0 (Winal), 0 (K’in). The 19 uses asymmetric placement with partial finger extension on the dominant hand. The 10 forms a unique two-person symmetric grasp between Ruler 1 and 16. The 0s are FlatB. Verification comes from resolving the missing death date in the hieroglyphs and fitting the overall mathematical framework. The hand signs complete the dynastic numerology, marking the last calendar round sum of 16, ending in the 9th Bak’tun, with the symmetric 10 emphasizing closure through boundary symmetry. This ties into equations elsewhere by echoing the cycle’s start on the East Panel.

Detailed Numerical Breakdown

The epoch (Long Count 0.0.0.0.0) corresponds to August 11, 3114 BCE in the proleptic Gregorian calendar (an extension of the Gregorian system backward in time for consistency). This alignment uses the Goodman-Martinez-Thompson (GMT) correlation, the most widely accepted among Maya scholars. The GMT assigns this epoch to Julian Day Number (JDN) 584,283.

• JDN is a continuous count of days since January 1, 4713 BCE (noon UTC), used by astronomers for date conversions.

Compute the JDN for the Date

Add the total Maya days to the epoch JDN:

JDN = 584,283 + 1,416,120 = 2,000,403

Convert JDN to Gregorian Date

Using standard astronomical conversion formulas (such as those from the U.S. Naval Observatory), JDN 2,000,403 maps to October 21, 764 AD.

• This accounts for leap years, calendar drifts, and the switch from Julian to Gregorian rules (though for dates in 764 AD, the proleptic Gregorian is used to avoid anachronisms).

• Note: The Maya didn’t use leap years; their system is a pure day count. The conversion formula handles Gregorian leap rules (divisible by 4, except centuries not divisible by 400).

Potential Variations

The exact Gregorian date can shift by 1–2 days if using slight variants of the GMT correlation (e.g., GMT+2 = 584,285 gives October 23, 764 AD). However, the standard GMT (584,283) is confirmed by astronomical events in Maya inscriptions (like eclipses) and cross-referenced with other calendars, leading to October 21, 764 AD as the accepted equivalent. This date falls in the Classic Maya period, aligning with historical events like rituals on Altar Q in the paper.

This process demonstrates how the Long Count precisely tracks time over millennia, allowing modern scholars to sync it with our calendar.

Maya Long Count to Gregorian Conversion Key

The Maya Long Count uses a 5-number “code” (Bak’tun.K’atun.Tun.Winal.K’in) to count days from August 11, 3114 BCE (using the standard GMT correlation of 584283). Each unit multiplies as follows to find total days elapsed:

To convert:

1. Compute total days = (Bak’tun × 144,000) + (K’atun × 7,200) + (Tun × 360) + (Winal × 20) + (K’in × 1).

2. Add to epoch JDN (584,283) for the full JDN.

3. Convert JDN to Gregorian date (using proleptic rules for ancient dates).

Example Conversions from the Paper

These show the breakdown for Altar Q’s deciphered dates, with verified Gregorian equivalents.

| Long Count | Bak’tun Days | K’atun Days | Tun Days | Winal Days | K’in Days | Total Days | JDN | Gregorian Date |

| 9.0.2.0.0 | 1,296,000 | 0 | 720 | 0 | 0 | 1,296,720 | 1,881,003 | Nov.28, 437 AD |

| 9.16.13.12.0 | 1,296,000 | 115,200 | 4,680 | 240 | 0 | 1,416,120 | 2,000,403 | Oct.25, 764 AD |

| 9.17.5.0.15 | 1,296,000 | 122,400 | 1,800 | 0 | 15 | 1,420,215 | 2,004,498 | Jan.11, 776 AD |

| 9.19.10.0.0 | 1,296,000 | 136,800 | 3,600 | 0 | 0 | 1,436,400 | 2,020,683 | May 4, 820 AD |

These revelations from the secret Mayan sign language highlight esoteric numerals. Forms vary: extended fingers for 0, symmetry for multiples of 5, unique features for others. They resolve missing hieroglyph data, tying to deaths, rituals, and time periods in the 9th Bak’tun. This makes Ancient Maya history more tangible through precise, verifiable dates.

Implications and Future Directions

Sandoval’s decipherment implies that Maya scribes employed a complementary hand-sign script, enhancing textual richness beyond hieroglyphs. This discovery could reshape understandings of Maya communication, suggesting that partial hieroglyph-only readings miss critical data. The 11 deciphered hand signs, though partial, provide a solid base for future research, potentially extending to other Maya sites.

The study acknowledges limitations, noting that the focus on Altar Q constrains broader applicability. Future work might test this script across additional monuments. Refining hand-sign values and exploring their linguistic or ritual roles. Sandoval thanks contributors like Edwin Barnhart and Barbara MacLeod for reviews and data, underscoring the collaborative effort behind this breakthrough.

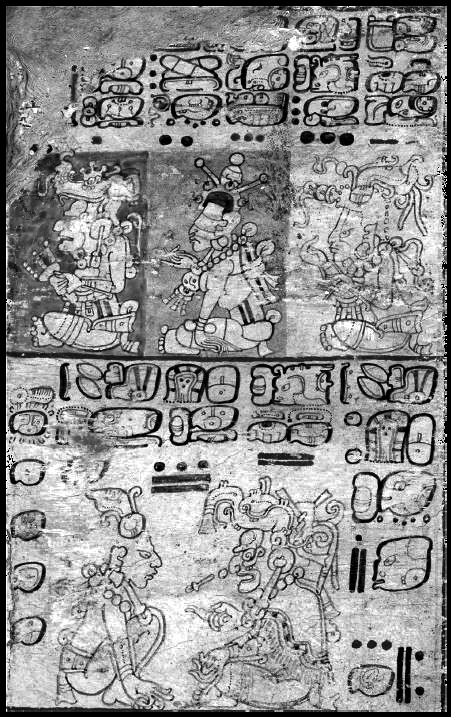

Visual and Structural Insights from Altar Q

Altar Q’s design, with its four side panels and upside-down topside inscription, reflects a cosmologically oriented foursquare layout. Figures from the Dresden Codex, illustrate similar hand variations, reinforcing the script’s antiquity. Sandoval’s drawings and photographs, alongside Linda Schele’s interpretations, visually support the analysis. Thus, making the secret Mayan sign language tangible.

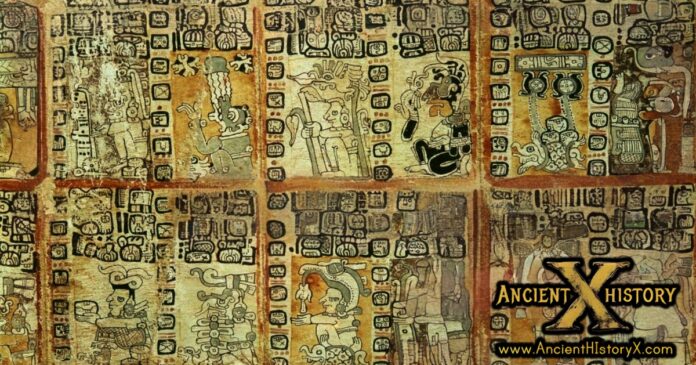

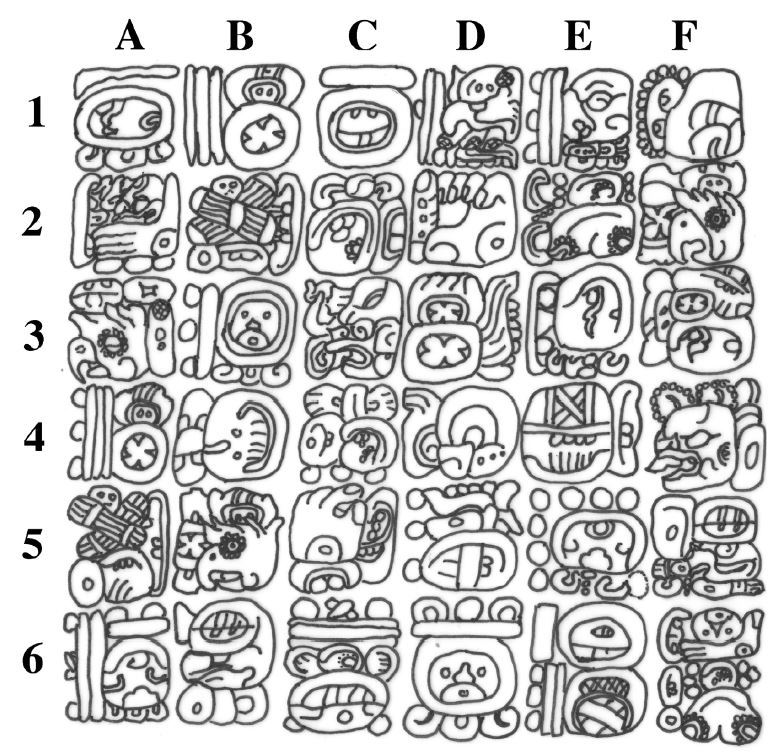

Image: Unique hand formations in the Maya Dresden Codex. Created around the twelfth century, concerns calendrical phenomena and divination. The upper sections of its 9th page, shown here, exemplify the scribal integration of hieroglyphic-block writing, bar-and-dot numerals and figures with distinctly formed hands.The meaning conveyed by the hands is unknown. However, the patterning and variation in formal features, such as handshape and palm orientation, suggest that the hands are complexgraphic symbols. Image made available foruse by the World Digital Library and retrieved from the Library of Congress Web Archives at https://www.loc.gov/item/2021667917

Thoughts

In the shadows of Ancient Maya art, where hieroglyphs have long held court, Rich A. Sandoval uncovers a silent script etched into the very hands of depicted rulers; a revelation that challenges our grasp of how civilizations encode time and power.

Maya scribes wove secrecy into visibility, using asymmetry for odd numbers and symmetry for boundaries, mirroring the cyclical cosmos they revered. Sandoval’s work prompts us to question the completeness of history’s narratives, urging a reevaluation of ancient artifacts where the unspoken hand might hold the key to forgotten wisdom.

Love decoding the secrets of the Ancient Maya? Check out Ancient Mayan Masonry Science