Deep in the heart of ancient Mexico, the sprawling metropolis of Teotihuacan once rivaled Rome in scale and influence. At its peak during the Classic Period (ca. 150–650 CE), this urban giant housed up to 150,000 people in vast apartment compounds, traded with distant Maya cities, and hosted multicultural barrios from Oaxaca to the Gulf Coast. Yet for all its grandeur, pyramids towering over the Avenue of the Dead, murals bursting with mythic serpents, one mystery has long puzzled scholars: Did the Teotihuacan’s write?

Most experts said no. Joyce Marcus, in her 1992 survey of Mesoamerican scripts, flatly declared writing absent from the city. But in a seminal 2000 paper published in Ancient America, University of California, Riverside archaeologist Karl Taube flipped the script. Drawing on murals, ceramics, and stone carvings, Taube argued that Teotihuacan boasted a full-fledged hieroglyphic system. One that was complex, phonetic, and a direct ancestor to later Aztec writing. His evidence? Glyphs that repeat consistently, pair with bar-and-dot numbers, and label everything from places to priests.

A Multi-Ethnic Hub Begging for Records

Teotihuacan’s cosmopolitan nature demanded literacy. Zapotec immigrants carved a stone with the date 9 “L” in their script. Maya expatriates painted Early Classic texts in the Tetitla compound’s “Realistic Paintings.” Gulf Coast merchants and Purépecha artisans added to the mix. With foreign tongues and far-flung trade, how could administrators track tribute, alliances, or rituals without writing?

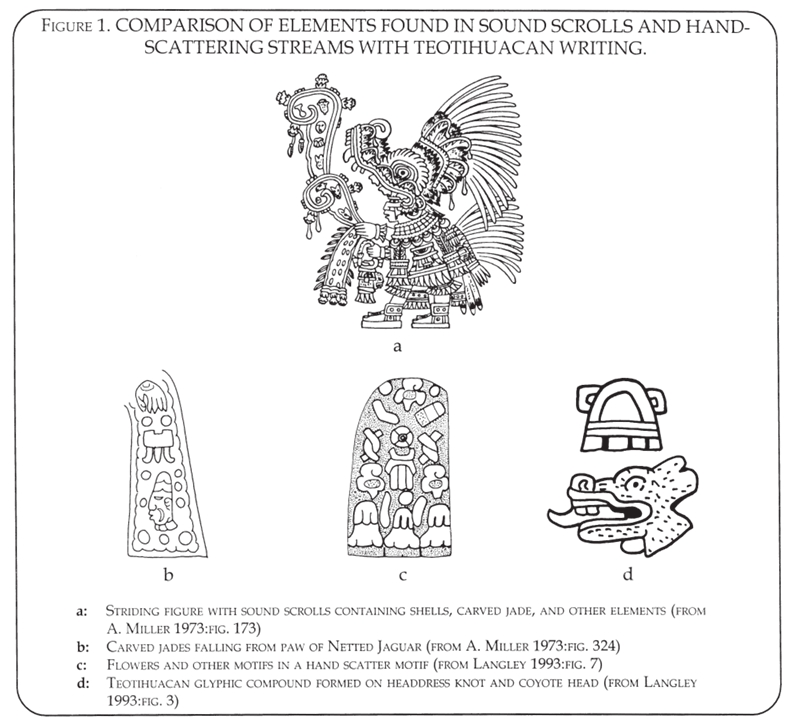

Taube stressed that writing wasn’t just pretty pictures; it’s “visually recorded speech.” Signs must be specific, repeatable, and tied to spoken words. Thus, allowing anyone to read them aloud identically. Aztec codices blur the line with pictorial scenes, but day names like Ce Cozcacuauhtli are true script: logographic, consistent, and pronounceable in Nahuatl. Maya lintels from Yaxchilan show the contrast; narrative art versus unambiguous glyphs naming captives and dates.

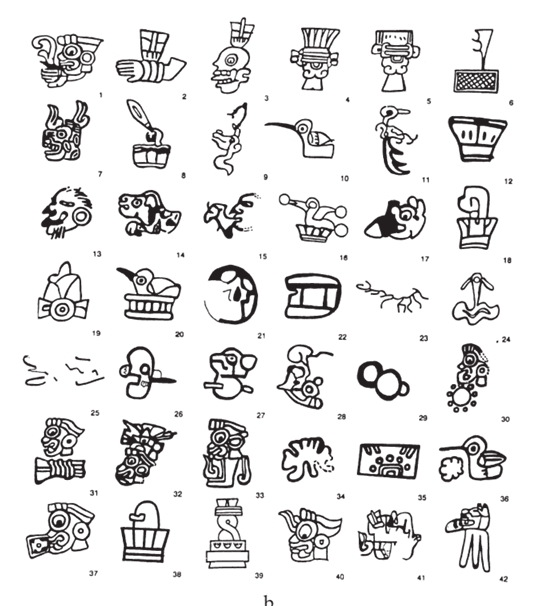

At Teotihuacan, Taube saw the same divide. Speech scrolls and hand-scattering streams overflow with symbols (shells, jades, flowers), but scholars like Thomas Barthel mistook them for “graphemes” forming texts. James Langley, in exhaustive studies (1986–1994), treated all signs as symbolic clusters, dodging the “glyph” label to avoid overreach. Taube disagrees: True writing emerges where signs reduplicate in varied contexts, expressing precise terms.

From Numbers to Names: Early Discoveries

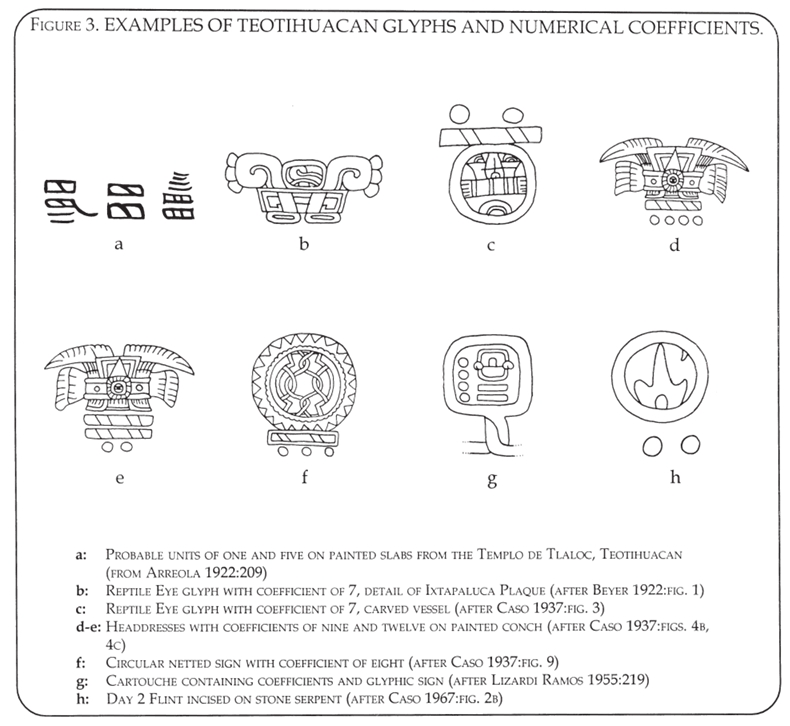

The trail started with math. In 1917, Manuel Gamio’s digs at the Templo de Tlaloc (within the Templo Mayor) uncovered slate slabs painted with thin lines and broad bars. A tally system echoed in colonial Tezcoco manuscripts. José María Arreola (1922) and Hermann Beyer (1921) ascertained these as numerals one and five respectively. Beyer also spotted the bar-and-dot versions on the “Ixtapaluca plaque” and a ceramic vessel.

Alfonso Caso pushed further. His 1937 paper documented coefficients up to 12 on conch shell headdresses and murals. By 1966, he identified “2 Flint” on a tecalli serpent: a trefoil projectile point framed in a circle, mirroring Xochicalco’s day sign. Numbers usually sit below glyphs (dots under bars) like Maya or Zapotec conventions. A Tetitla fragment with 14 (per César Lizardi Ramos) hints at the 365-day xihuitl calendar, though At Teotihuacan the 260-day tonalpohualli remains elusive. No full set of 20-day names survive, but coefficients denote attached signs as bona fide glyphs.

Murals That Speak: Tepantitla and Techinantitla

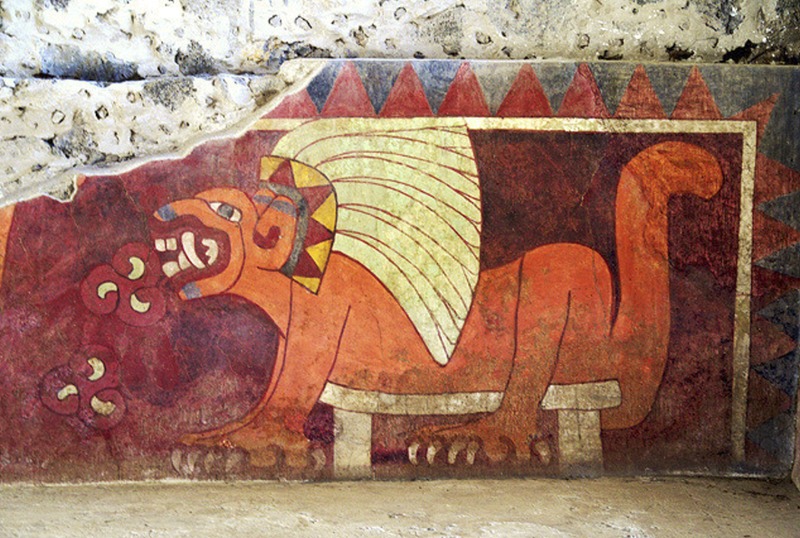

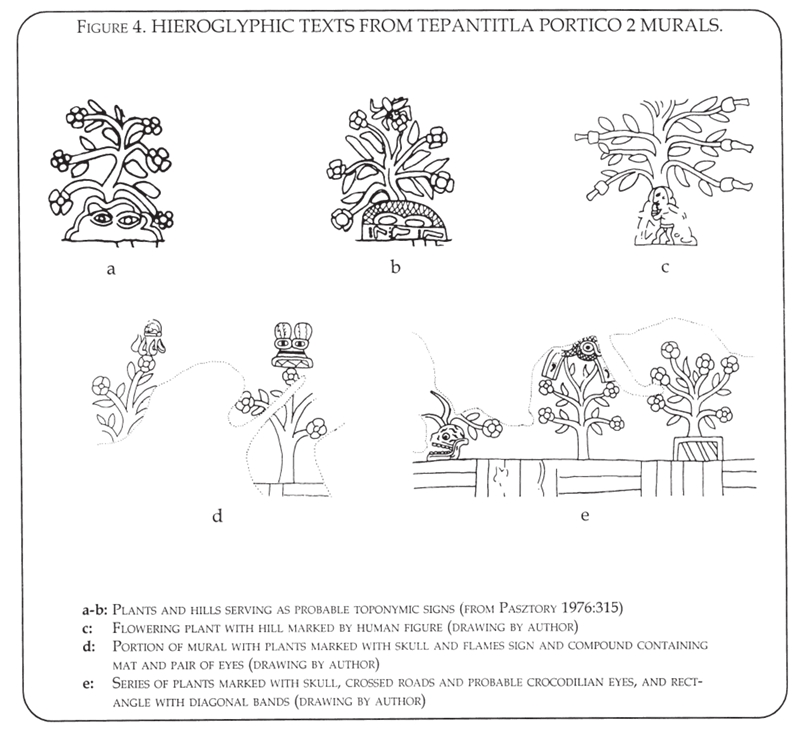

Excavations shaped the debate. In 1942, Tepantitla’s Portico 2 yielded murals of frenetic figures amid a glyphic treasure trove. Esther Pasztory (1974) added death imagery to the pallet, diagonal-banded rectangles, human figures on curves (hills?). Glyphs hover above or below flowering plants: paired eyes with crossed roads (perhaps a junction place), or crocodilian eyes evoking mythic beasts.

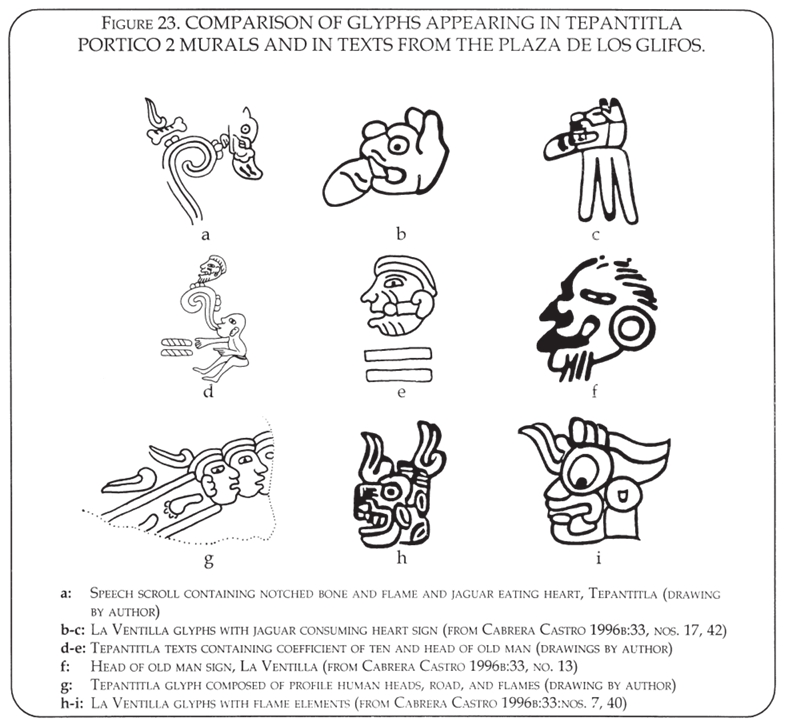

Techinantitla murals, reconstructed from fragments in U.S. museums, seal the deal. Plumed serpents rain on nine unique plants, each flower type matched by trunk glyphs. A red four-petaled bloom with blue centers drips water in some versions; its glyph shows a blue-petaled eye exuding trilobed drops. Another swaps in a green-feathered eye when water’s absent. Janet Berlo (1993) likened these to Aztec phonetic-pictographic toponyms, but Taube notes a key difference: no locative suffixes (like Aztec hill or water markers).

These aren’t random icons, they label specifics, repeatable across compounds. Pasztory tied Tepantitla’s flowering toponyms to Techinantitla’s, suggesting a city-wide naming system for sacred sites or tribute zones.

Precursor to Aztec Script?

Taube positions Teotihuacan writing as a bridge. Circular cartouches frame day signs; bar-and-dot math persists into Aztec times. Glyphs on headdresses (knot + coyote head) form compounds, like later Mixtec or Aztec names. Speech scrolls bear identifiers; priests or deities tagged mid-chant.

Critics like Joyce Marcus demanded phonetic proof, but Taube’s corpus delivers: consistent signs in diverse media (murals, vessels, stone), paired with numbers for dates or counts. Foreign scripts at the site prove literacy’s value; why import Zapotec or Maya without a local system?

Recent Research

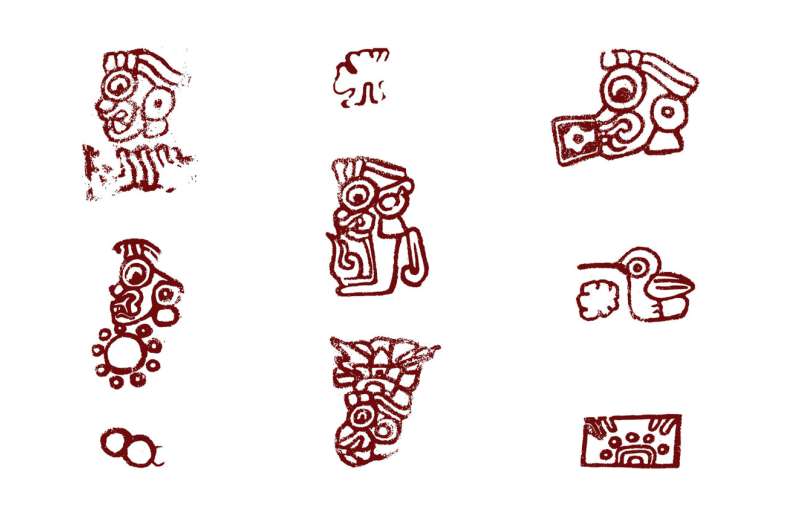

Building on Karl Taube’s foundational identification of Teotihuacan’s glyphic system, Magnus Pharao Hansen and Christopher Helmke have recently published a linguistic confirmation that pushes the debate into firmer terrain. Their 2025 study in Current Anthropology analyzes hundreds of glyphs across murals, ceramics, and stone carvings, demonstrating that the system meets criteria for true writing: consistent, phonetic, and structurally linguistic.

Dismissing as Taube did, signs as symbolic or decorative, they show how reduplication, semantic pairing, and rebus-like constructions encode speech in a repeatable, pronounceable way. Crucially, they back Taube that the underlying language was likely an early Uto-Aztecan tongue, Nahuatl, confirming that Teotihuacan was not only literate, but a linguistic ancestor to the Aztec world.

Rewriting Mesoamerican Literacy

Taube’s paper shattered the “writing-less Teotihuacan” myth. Pharao Hansen and Christopher Helmke confirm it. This was a mature system, influencing Xochicalco, Tula, and Tenochtitlan. It recorded toponyms, titles and calendars; bureaucracy for a superpower.

Future digs may yield codices or stelae, but murals already “speak.” As Taube concluded, Teotihuacan wasn’t mute; it spoke in glyphs, resonating across millennia.

Liked this deep dive check out Serapeum Science: Sarcophagi and the Sands of Time