Historical Context and Cultural Roots of Rongorongo

Rongorongo, a unique script from Easter Island, perhaps as old as time, but deemed by academics to have likely emerged after 1770. Possibly inspired by Spanish deeds during annexation, Fischer notes in 1997. Rapa Nui’s elite, including kings, nobility, and priests, used it to preserve oral traditions like genealogies, chants, and historical narratives, per Melka’s 2009 study. For example, tablets recorded victim lists, known as kohau ika, reflecting Polynesian traditions where “fish” symbolized sacrificial victims. Initially, these tablets held immense value, often hidden due to their perceived supernatural power. However, rongorongo’s use ended abruptly after 1862 due to Peruvian slave raids, epidemics, and economic exploitation. Missionary Eyraud reported around 2,000 tablets in 1864, but most were destroyed or lost soon after.

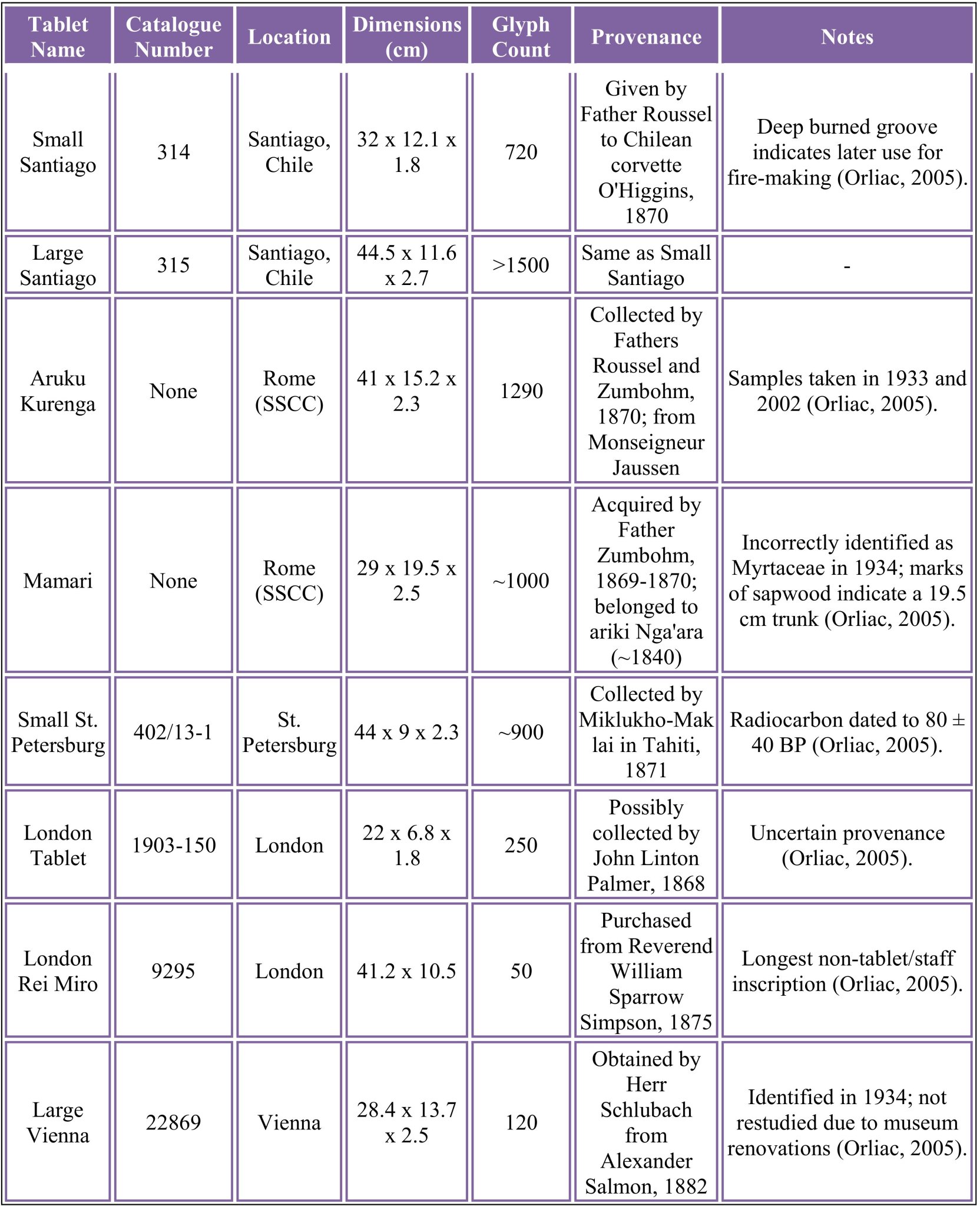

Today, none remain on Easter Island; surviving artefacts reside in museums in Santiago, Rome, St. Petersburg, London, and Vienna. Some scholars suggest Marquesas glyphs influenced rongorongo’s creation, indicating Polynesian cultural exchange. Additionally, its decline mirrors Rapa Nui’s broader cultural collapse in the 19th century, driven by external pressures and deforestations. By 1869, when Father Zumbohm collected the Mamari tablet, traditional knowledge was nearly lost. This history reveals Rongorongo’s profound role in Rapa Nui society, its elite-driven creation, and its tragic disappearance amid colonial impacts.

The Tablets and Their Sacred Material

Rongorongo tablets, crafted from Thespesia populnea, reveal the skilled artistry of Rapa Nui carvers. This sacred Polynesian tree, known as makoi, belongs to the Malvaceae family. Often pinkish when young, it turns dark red with purple glints as it matures, growing up to 15 meters tall on Polynesian shores. In Tahiti, makoi lined marae platforms, a spiritual practice for sacred spaces. Similarly, in the Gambier Islands, artisans carved divine figures from its wood, showing its revered status. Additionally, its yellow flowers and dye, extracted from fruits, leaves, and bark, held deep meaning, often linked to red and yellow hues used in Rapa Nui moai statues and body paintings.

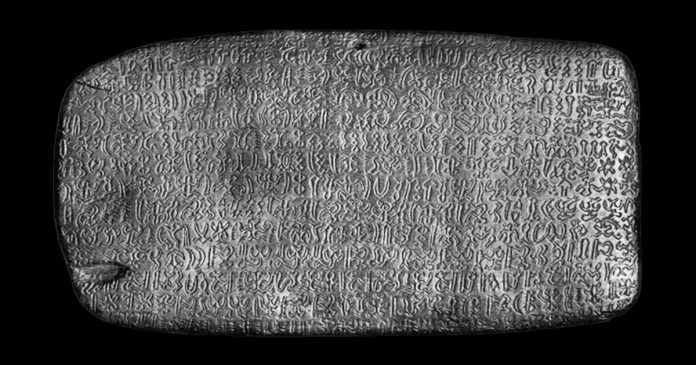

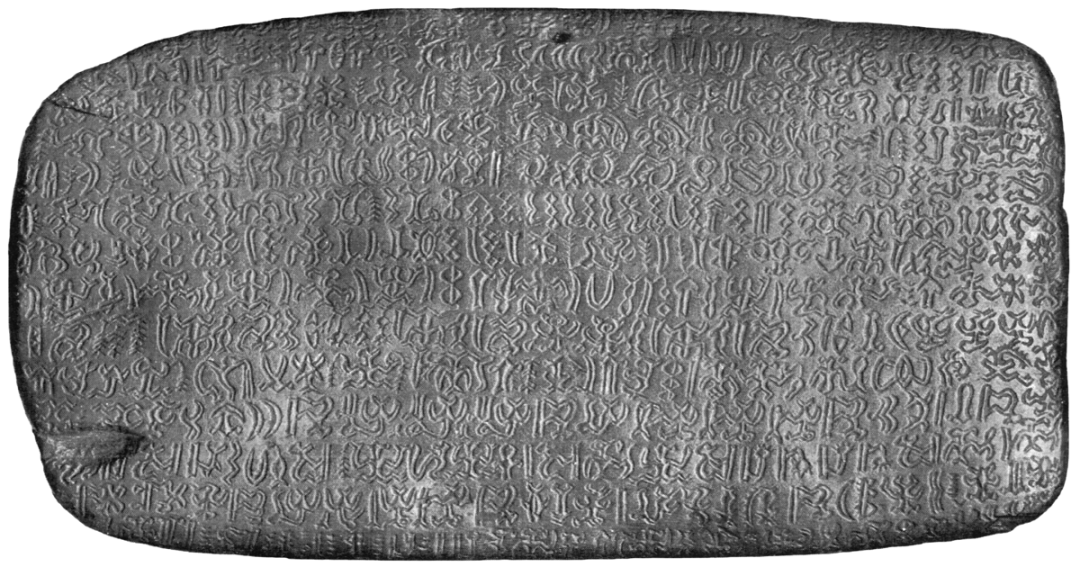

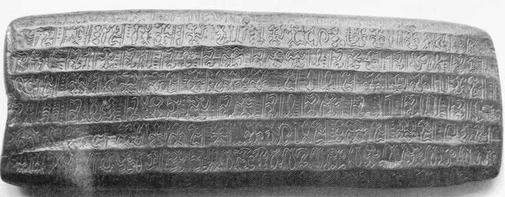

For example, the Small Santiago tablet, 32 cm long with 720 glyphs, shows a burned groove from later fire-making use. Another tablet, the Mamari, measures 29 cm wide with 1000 glyphs, displaying sapwood marks that indicate a 19.5 cm trunk, suggesting a 15-meter tree. The Large Santiago tablet, 44.5 cm long, holds over 1500 glyphs, while the London Rei Miro, 41.2 cm wide, features 50 glyphs, making it the longest non-tablet inscription. Moreover, the Large Vienna tablet, 28.4 cm long with 120 glyphs, reflects the same material choice. Carvings align with wood fibbers, perpendicular to ligneous rays, ensuring the tablets’ durability. This technique highlights the precision of Rapa Nui carvers, who worked with tools suited for fine detail. Tablets like the Small St. Petersburg, 44 cm long with 900 glyphs, further demonstrate this craft.

Total Deforestation

However, makoi’s availability dwindled after Rapa Nui’s deforestation around 1650, as European accounts later noted no large trees. Scholars believe Polynesian settlers introduced makoi to Rapa Nui in the 8th century, likely bringing it for its spiritual value. In Polynesian culture, makoi often symbolized divine connection, used in rituals and offerings. For instance, its wood crafted posts for sacred offerings in various islands, Orliac adds. On Rapa Nui, oral traditions rarely mention makoi, yet its use in rongorongo tablets suggests a deep cultural role. This sacred material, chosen for its durability and meaning, underscores rongorongo’s spiritual significance in Rapa Nui society, linking their script to broader Polynesian traditions.

_edit1.jpg)

Script Features, Structural Insights and Musical Cadences

Rongorongo’s script fascinates researchers with its unique features and complex structure. It uses an inverted boustrophedon style, starting bottom-left on the verso, alternating directions each line, then continuing down the recto. This scriptura continua lacks clear word or sentence divisions, except possibly on the Santiago Staff. Around 120 basic glyphs form the script, including pictographic signs like birds, fish, and the sun, with potential phonetic values, Fischer adds. For instance, ra’a may represent the sun, while manu could mean bird. However, numerous glyph variants arise from scribal creativity, wood type, and carving tools, complicating analysis. Harmonic sequences, repetitive dyadic or triadic patterns, resemble musical cadences. For example, on the Small Santiago tablet, line Sb3 shows /700.10 – 700.10 – 700.10 – 700.61/, possibly listing victims as fish. Another sequence, Ra4 on the Mamari tablet, /4.90f – 4.90f – 20f.3 – 4.90f/, uses a clef glyph /4/.

These triadic formations often parallel Rapa Nui oral traditions, like chants stating “X copulated with Y: issued Z”. Melka identifies four syntax types in 2009: elementary, with short clusters on Cb3-Cb4; scrambled, showing permutations on Ab5-6; loose, with high entropy on Br8; and combined, mixing patterns on Ra3-Ra4. Glyph /76/ might function as a subject marker (ko), often seen in genealogies, Davletshin proposes in 2002. Additionally, allography-glyph variations akin to font families-adds further complexity.

These structures suggest Rongorongo recorded oral traditions, such as kohau ika victim lists, pāta’uta’u recitations, or kai kai string figure chants, per Melka. For instance, Polynesian chants like “He Tangi o Te Māori” use “ko” to list murdered men, Campbell mentions in 1971. Similarly, “Tae-Reka” describes victims in the kohau ika genre. Moreover, the script’s artistic finesse, with neatly spaced and trimmed outlines, indicates skilled scribes. Longitudinal flutes on tablets like Aruku Kurenga aided reading and protected glyphs. This blend of structure and artistry reveals Rongorongo’s depth, likely capturing Rapa Nui’s cultural narratives.

Decipherment Challenges and Research Efforts

Deciphering rongorongo poses immense challenges, keeping its secrets locked. The script’s limited corpus, with only 14,000 glyphs across 25 artefacts, lacks bilingual texts for comparison. Additionally, glyph variations, driven by scribal creativity, wood type, and carving tools, create inconsistencies. For instance, a single glyph like the bird sign might appear in multiple forms. This allographic variation, akin to font families in typography, complicates identification. Moreover, rongorongo’s scriptura continua, lacking clear word or sentence breaks, further hinders segmentation. Thomas Barthel’s 1958 transliteration system, though foundational, requires updates due to numbering inconsistencies. Scholars also debate the script’s nature, unsure if it’s syllabic, logographic, mnemonic, or a mix. Some glyphs, like /76/, might act as subject markers (ko) in genealogies, yet this remains unconfirmed.

The absence of archaeological context, as no tablets appear in Rapa Nui digs, adds another layer of difficulty. Furthermore, Rongorongo glyphs don’t match stone carvings on the island. Despite these obstacles, researchers persist with various approaches, Melka highlights. Fischer’s 1997 work traces Rongorongo’s history and offers tentative glyph interpretations, focusing on Polynesian parallels. Meanwhile, Barthel’s early analysis identified harmonic sequences, laying groundwork for structural studies. Konstantin Pozdniakov’s 1996 statistical analysis examines glyph patterns, seeking repetition clues. Similarly, Paul Horley’s 2005 research explores allographic variations, aiming to standardize glyph forms.

New Techniques

Ethnographic comparisons also play a role, as Fischer links Rongorongo to oral traditions like kai kai chants. For example, Polynesian chants often use markers like “ko” for lists, supporting Davletshin’s hypothesis. However, without a Rosetta Stone-like text, progress remains slow. Computational methods, such as chi-squared collocation plots for bi-grams, offer hope. These tools could reveal hidden patterns, as Horley suggested in 2011. Additionally, Rongorongo shares traits with other undeciphered scripts, like Linear A and Indus Valley. Non-linguistic systems, such as Inka tokapu or the Voynich Manuscript, provide further context. Interdisciplinary efforts combining paleography, statistics, and ethnolinguistics might eventually unlock rongorongo. Until then, its mysteries endure, captivating scholars worldwide.

Future Research Directions and Cultural Legacy

Unlocking rongorongo’s secrets requires bold new approaches. First, more radiocarbon dating could confirm the script’s age. For example, the Small St. Petersburg tablet, dated to 80 ± 40 BP, suggests a range from 1680 to 1871. However, only one tablet has been dated, so testing others, like the Mamari or Large Santiago, might clarify if carvings predate European contact. Additionally, computational methods offer promising tools. Similarly, Horley’s 2011 research advocates for standardizing glyph forms to reduce allographic confusion. Linking Rongorongo to oral traditions provides another avenue, as Campbell highlighted in 1971. For instance, Polynesian chants like kai kai use binary rhythms, which may mirror rongorongo’s harmonic sequences. Moreover, chants such as “He Tangi o Te Māori” list murdered men with the marker “ko,” supporting Davletshin’s 2002 idea that glyph /76/ serves a similar role. Interdisciplinary efforts, combining paleography, statistics, and ethnolinguistics, might finally decode the scrip. Fischer’s 1997 ethnographic work, comparing Rongorongo to Marquesas glyphs, also deserves further exploration.

Beyond research, rongorongo’s cultural legacy endures. It embodies Rapa Nui’s elite knowledge, preserving oral traditions like genealogies and love charms, as Melka stated in 2009. Tablets, once sacred, held supernatural power, often concealed by their owners. Today, they reside in global museums, from Santiago to Vienna, sparking worldwide curiosity. For example, the Mamari tablet, collected in 1869, represents a lost era of Rapa Nui scholarship. Similarly, the London Rei Miro, acquired in 1875, captivates visitors with its 50 glyphs. Rongorongo also inspires modern Rapa Nui identity, symbolizing resilience despite 19th-century cultural collapse. Its undeciphered status fuels fascination, drawing scholars and enthusiasts alike. Ultimately, Rongorongo stands as a testament to Rapa Nui’s ingenuity, preserving their voice for future generations.

References:

- Fischer, S. R. (1997). Rongorongo: The Easter Island Script.

- Melka, T. S. (2013). Harmonic-like Structures in the Rongorongo Script.

- Melka, T. S. (2009). Linearity in Rongorongo Script.

- Orliac, C. (2005). Botanical Identification of Rongorongo Tablets.

- Zizka, G. (1991). Polynesian Flora Studies.

- Campbell, R. (1971). Polynesian Oral Traditions.

- Davletshin, A. (2002). Rongorongo Glyph Analysis.

- Horley, P. (2011). Allographic Variations in Rongorongo.

- Harris, R. (2010). Computational Methods for Undeciphered Scripts.