Imagine a terrace above the Salmon River, winds howling through a world locked in ice, some 16,000 years ago. Beneath a sky vast and unyielding, hands, both calloused and deliberate, shape stone into tools, their edges sharp with purpose. Nevertheless, these are not the fluted points of Clovis lore, those heralded icons of a supposed “first” American culture. No, these are stemmed points, older by millennia, whispering a tale that stretches beyond the glaciers, across oceans, to the Northwest Pacific Rim. At the Cooper’s Ferry site in western Idaho, archaeologists have unearthed a truth that defies the dogma of textbooks: the peopling of the Americas began earlier than we dared believe, and its roots may lie far from the Beringian plains.

What if the story we’ve clung to, stating Clovis as the genesis, 13,000 years ago, was but a chapter, not the opening verse? The discovery of 14 stemmed projectile points, dated to ~15,785 calibrated years before the present (cal yr B.P.), shatters that narrative. Buried in loess, kissed by carbonate from the ancient Rock Creek Soil, these artefacts predate Clovis by 3,000 years and even outstrip earlier finds at the same site by 2,300 more. For this reason, this isn’t just a dig; it’s a rebellion against time itself, a call to rethink who we are and where we came from. Hence let’s journey into this deep past, where science meets mystery, and the echoes of forgotten artisans beckon us to listen.

The Discovery at Cooper’s Ferry: A Glimpse into the Deep Past

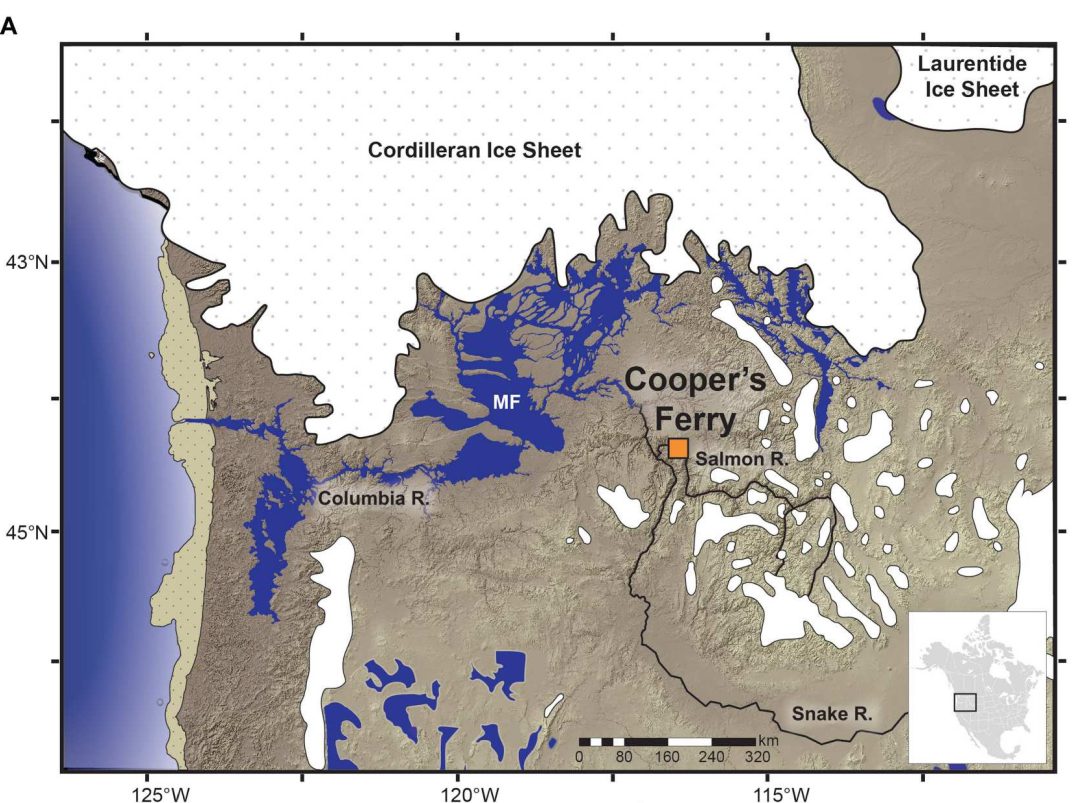

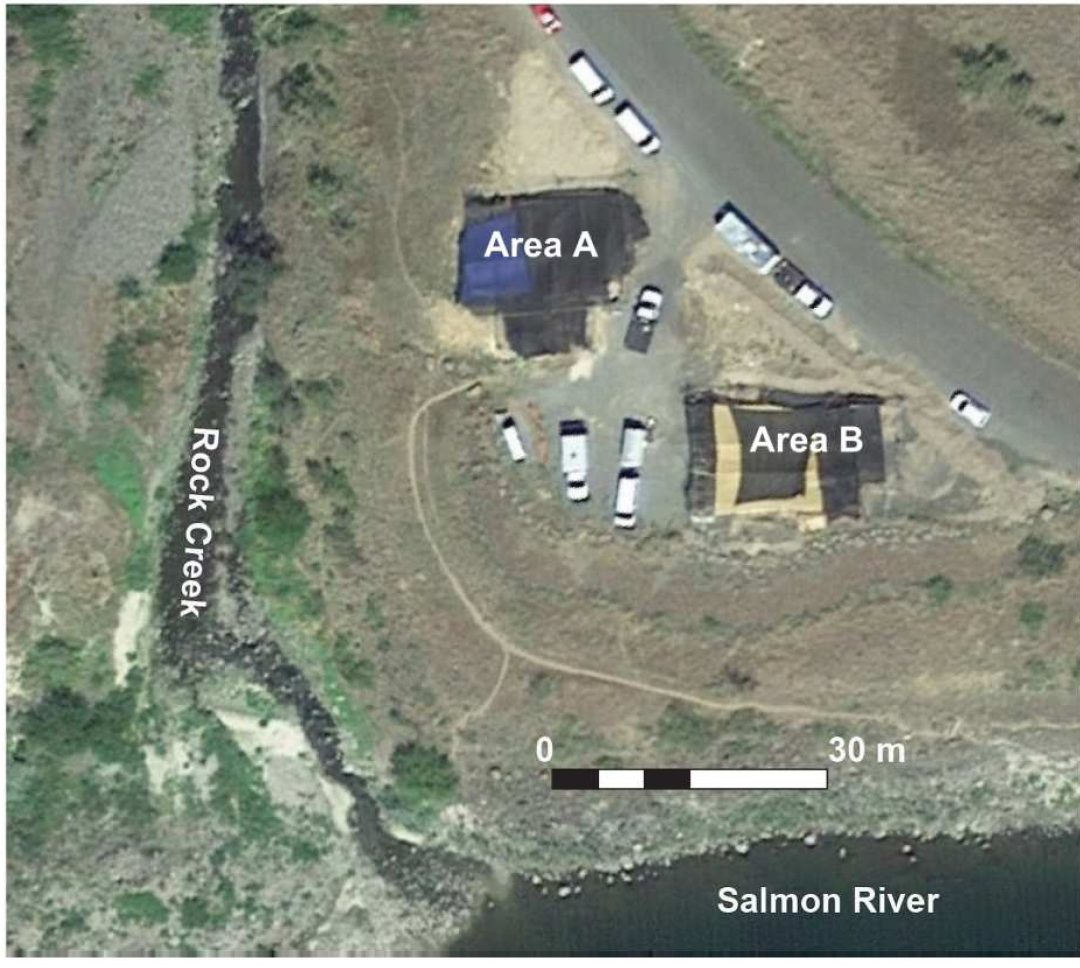

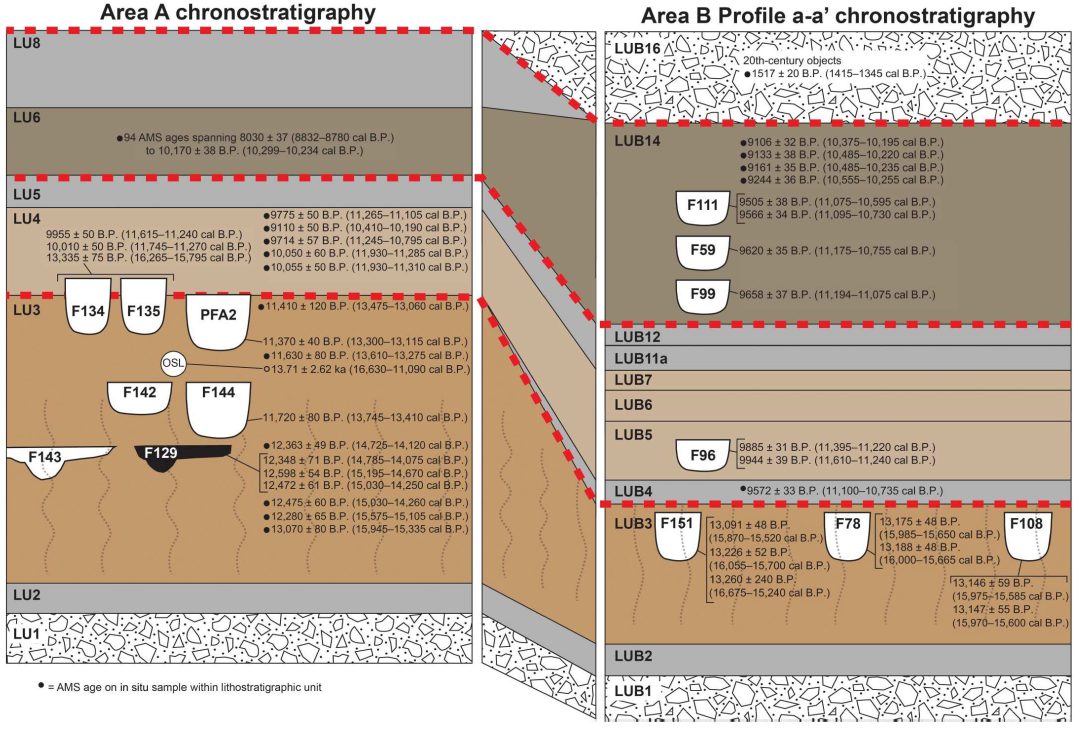

Picture the scene: western Idaho, where the Salmon River carves its quiet path through a land once shadowed by the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets. Here, at Cooper’s Ferry, archaeologists led by Loren G. Davis peeled back layers of earth- Loess, gravel and sand, unveiling a story etched in sediment. From 2012 to 2018, in an area dubbed “Area B,” they found something extraordinary: a tool assemblage older than the Clovis horizon, nestled in lithostratigraphic unit 3 (LUB3), a loess blanket laid down at the tail end of Marine Isotope Stage 2, when glaciers sealed the interior route into the Americas.

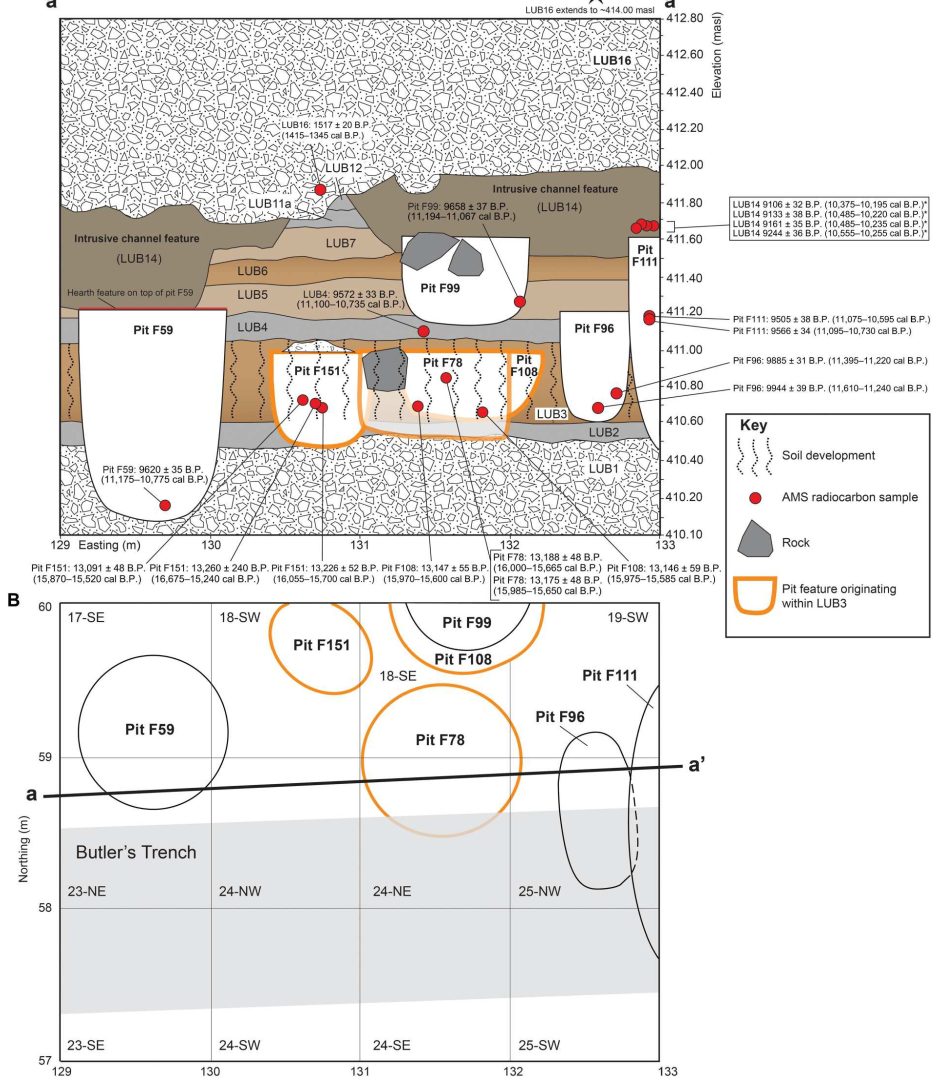

This wasn’t a fluke. Earlier digs in Area A had hinted at antiquity, revealing stemmed points dated to ~13,200 cal yr B.P. (Davis et al., 2019). But Area B pushed the clock back further. Three pit features, F78, F108, F151, yielded a trove: 14 stemmed points, hundreds of bone fragments, debitage, charcoal, and fire-cracked rock. These pits, dug into LUB3, were capped by sediment and time, their contents coated in carbonate from the Rock Creek Soil, a paleosol dated between 16,450 and 14,160 cal yr B.P. (Fryxell et al., 1968). The tools weren’t scattered; they were cached, perhaps offerings to a world both provider and predator.

Inhabitants of Copper Ferry

Who were these people? The bones whisper of a diet tied to the land. Fragments of an extinct horse among them, while the tools speak of skill honed over generations. The Younger Dryas, a cold snap from 12,900 to 11,700 cal yr B.P., loomed on the horizon, but these artisans lived before its chill, in a time when Megafauna roamed and the Pacific coast offered a lifeline. This discovery, detailed in Science Advances (DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ade1248), isn’t just about artefacts; it’s a portal to a forgotten epoch, a testament to human resilience in a world we can scarcely fathom.

The Tools That Challenge Time: Stemmed Points and Their Secrets

Hold one of these stemmed points in your mind’s eye: small, elongate, crafted from cryptocrystalline silicate or fine-grained volcanic rock, sourced within 10 kilometres of the site. Unlike the broad, fluted elegance of Clovis points, these are subtler, biconvex or plano-convex, with collateral flaking and single-beveled edges, some bearing weak shoulders and contracting stems. Twelve of the 14 show resharpening, signs of a life lived hard and long. The smallest, catalogued as 73-54688, mirrors a diminutive point from Texas’ Gault site, dated to ~16,000 years by optically stimulated luminescence (Williams et al., 2018). These aren’t mere tools; they’re relics of a technological tradition that defies our timeline.

Compare them to Clovis: those fluted points, iconic since their discovery in New Mexico in the 1930s, were once deemed the Americas’ oldest at 13,000 cal yr B.P. (Haynes, 2002). Yet here, in Idaho, we find stemmed points, some larger, bifacially reduced from preforms and predating them by millennia. They resemble pre-Clovis finds elsewhere: the Friedkin site in Texas (15,500 years, Waters et al., 2018) or Mexico’s Santa Isabel Iztapan, linked to mammoth bones and a 14,500-year-old tephra (Mirambell, 1978). But Cooper’s Ferry stands apart, its assemblage vast enough to trace a lineage.

What has Copper Ferry to teach us?

What do they tell us? These points evolve over time at the site, their haft morphometry shifting from subtle shoulders to forms like Lind Coulee and Windust, known in the Pacific Northwest (Rice, 1972). This isn’t a static craft; it’s a dance of adaptation, a thread woven through the late Pleistocene. They challenge the Clovis-first dogma, suggesting a deeper root system. Perhaps, one that stretches across the Pacific, where similar tools whisper from the shadows of another continent. Can a stone tool rewrite history? These do, with every flake and bevel.

Dating the Unthinkable: How Science Pinned 16,000 Years

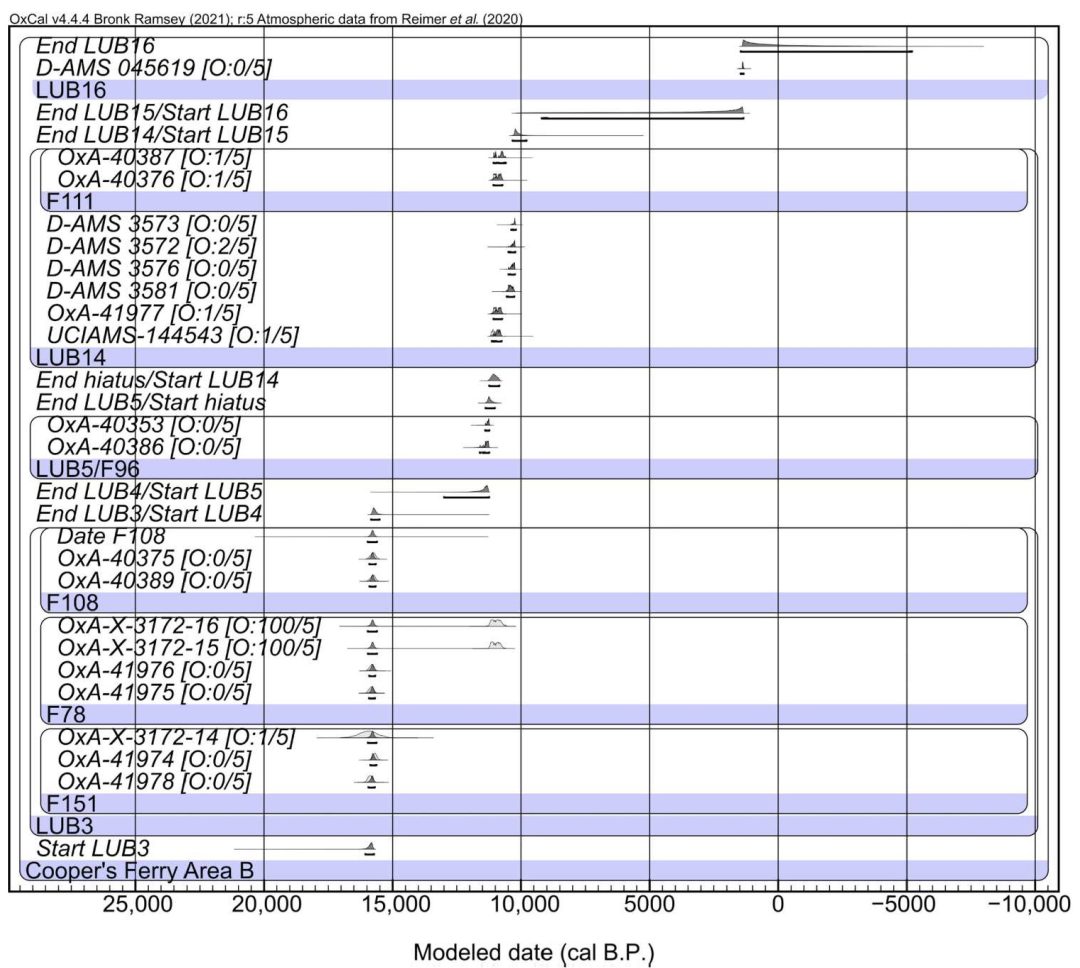

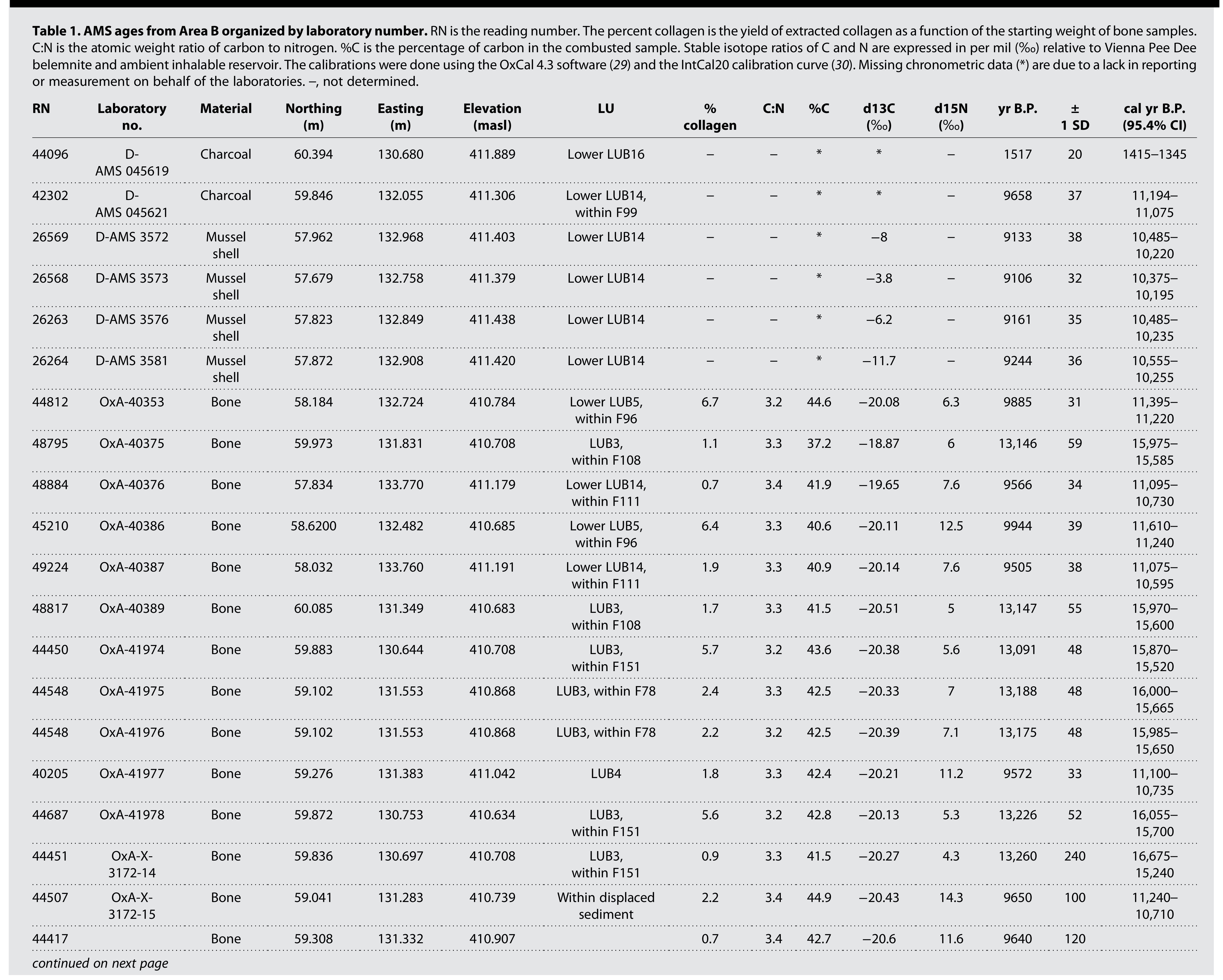

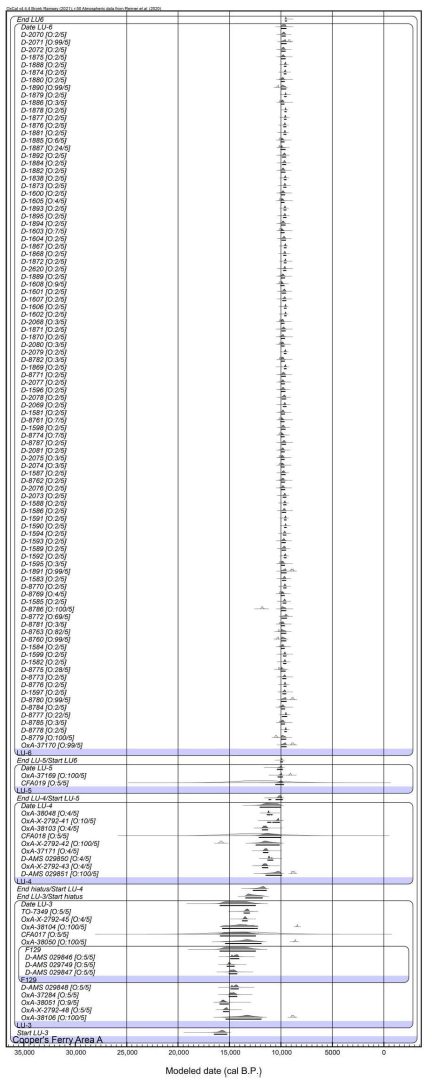

How do we know these points are 16,000 years old? Science, that relentless seeker, offers answers through radiocarbon and Bayesian magic. In Area B, seven animal bone fragments from pits F78, F108, and F151 yielded ages between 13,260 ± 240 and 13,091 ± 48 yr B.P., calibrating to 16,675–15,240 cal yr B.P. (Davis et al., 2022). A fragment from F78 clocks in at 15,882–15,719 cal yr B.P., another from F108 at 15,975–15,590. These aren’t outliers; Bayesian modelling tightens the noose: LUB3 begins at 16,045–15,725 cal yr B.P., its pit features clustering at 15,955–15,625. The loess ends at 15,845–15,530, eroded away before Clovis ever touched this soil.

Moreover, Area A’s chronology aligns, with 94 new radiocarbon dates on mussel shells from LU6 pinning LU3’s span at 16,500–15,250 to 13,450–11,800 cal yr B.P. Hence, no reservoir offset muddies the waters. In addition, modern mussels from the Salmon River confirm it (Davis et al., 2022). Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) fills gaps, like LUB4’s 73-15-OSL-Lu2-5, bridging millennia. This isn’t guesswork; it’s precision etched in carbon-14 and light-trapped quartz, a dialogue between earth and isotope.

Copper Ferry and the shattering of the Dogma

Yet, isn’t there poetry in this rigor? These dates aren’t cold numbers; they’re a heartbeat from the Pleistocene, pulsing through loess and bone. They place humans here when glaciers barred the interior, forcing a coastal path—a Pacific corridor now drowned beneath rising seas (Mandryk et al., 2001). In short, the Rock Creek Soil, forming after these pits were dug, seals the deal: carbonate coats the artefacts, a timestamp from 16,450–14,160 cal yr B.P. Science proves what intuition whispers: we’ve underestimated our ancestors’ reach.

deepest excavation units showing distribution of pit features and trench excavation placed by Butler (B). Excavation unit numbers and quadrant designations are shown in each 1 m–by–1 m square (e.g., 23-SE).

Echoes from the Pacific Rim: A Hypothesis of Origins

Now, cast your gaze across the Pacific, to Hokkaido, Japan, where the Late Upper Paleolithic (LUP) blooms from 21,400–16,170 cal yr B.P. Here, bifacial stemmed points, collateral-flaked and single-beveled mirror those at Cooper’s Ferry (Izuho & Sato, 2007). These pre-Jomon tools, predating the ceramic dawn of ~14,700 cal yr B.P. (Nakazawa et al., 2011), hint at a technological kin. Before them, a blade-point industry thrived from 32,000–20,000 cal yr B.P., a precursor to this tradition (Morlan, 1967). Could this be the cradle of the Americas’ first tools?

Davis and his team hypothesize so. The First Americans, sharing ancestry with Siberia and East Asia, diverged after ~25,000 cal yr B.P. (Raghavan et al., 2015), entering the Americas post-19,500 (Moreno-Mayar et al., 2018). Paleogenetics can’t pinpoint their launchpad, but these points, small, stemmed and resonant, suggest a Northwest Pacific origin, perhaps 22,000–16,000 years ago. Jomon DNA doesn’t match Native Americans (Adachi et al., 2011), but these pre-Jomon artisans predate that shift. Their tools, found in Hokkaido’s Shirataki sites, sing a song of continuity.

Imagine it: a coastal migration, boats hugging the ice-fringed Pacific, carrying this craft from Japan to Alaska, down to Idaho. The Kelp Highway hypothesis supports this, seaweed-rich shores sustaining travelers (Erlandson et al., 2007). No Beringian land bridge needed; the ice was a wall, the sea a road. These stemmed points, then, are not just tools but emissaries, linking continents in a dance of stone and survival. Can a hypothesis bridge oceans? This one dares to try.

Rewriting the Peopling of the Americas: Beyond Clovis Dogma

For decades, Clovis reigned supreme, 13,000 cal yr B.P., the benchmark of America’s peopling (Fiedel, 1999). Its fluted points, tied to mammoth hunts, fueled a narrative of pioneers crossing Beringia. But cracks appeared: Monte Verde, Chile, at 14,500 cal yr B.P. (Dillehay, 1997); Paisley Caves, Oregon, with 14,300-year-old coprolites (Jenkins et al., 2012). Cooper’s Ferry, at 16,000, drives the stake deeper. Consequently, Clovis wasn’t first; it was a latecomer.

This shift upends more than dates. The ice-free corridor, once the holy grail, was closed at 16,000 cal yr B.P. (Pedersen et al., 2016). A Pacific route, coastal, vibrant, emerges as the path. Stemmed points at Cooper’s Ferry align with pre-Clovis sites, not Clovis successors, suggesting multiple waves, diverse traditions. The Americas weren’t a blank slate awaiting Clovis; they were a tapestry, woven earlier, richer.

Why resist this? Dogma dies hard. Clovis-first was tidy, a creation myth for archaeologists. But science, like life, thrives on disruption. Cooper’s Ferry demands we shed that skin, embrace a messier truth: humanity’s journey here was vast, varied, older than we knew. It’s not just about when, but who, in this case, artisans from a Pacific cradle, defying ice and time. Isn’t that a story worth telling?

What It Means: Humanity’s Dance with the Cosmos

Step back, beneath the stars. In sum, these stemmed points aren’t relics; they’re voices from a chorus spanning millennia. To illustrate this, they speak of resilience, ingenuity, a thread from Hokkaido to Idaho, woven into the fabric of the cosmos. In my books, I wrote of humans seeking meaning amid chaos; here, we find it in stone, in the hands that shaped it 16,000 years ago. Indeed, this isn’t just archaeology, it’s a mirror to our soul. Therefore, we’re not separate from this tale. The Pacific Rim hypothesis ties us to Asia’s ancient artisans, a reminder that borders are illusions, time a fleeting veil. However, be it free will or fate, these people chose to craft, to survive, to leave a mark. Their legacy challenges us: to question, to connect, to see ourselves as part of the All. Are we passengers or creators in this dance? Cooper’s Ferry suggests both.

Conclusion: A Call to Wonder

So, here we stand, atop loess and history, peering into a past that reshapes our present. As a result, Cooper’s Ferry’s stemmed points, standing 16,000 years old, dissolve the Clovis myth, pointing to a Pacific origin, a coastal odyssey. They’re more than tools; they’re a testament to human spirit, a whisper from the Pleistocene that we’re older, broader, than we thought. Science pins the date, but imagination fills the gaps: who were they, these travellers, and what drove them across seas and ice?

This isn’t the end, but a beginning. A call to shed dogma, to marvel at our roots, to feel the unity beneath our diversity. Whether you read this by chance or choice, ponder it. Finally, Americas’ tale is rewritten, and we’re all its heirs, stardust, scattered across time, shaping our destiny with every step. Let’s walk it with eyes wide open.rdust, scattered across time, shaping our destiny with every step. Let’s walk it with eyes wide open.

References

- Davis, L. G., et al. (2022). Science Advances, 8(51), eade1248. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ade1248

- Dillehay, T. D. (1997). Monte Verde: A Late Pleistocene Settlement in Chile. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Erlandson, J. M., et al. (2007). Journal of Island & Coastal Archaeology, 2(2), 161-174.

- Raghavan, M., et al. (2015). Science, 349(6250), aab3884.