In the summer of 1999, a Massachusetts quarry turned into a proving ground for obelisk raising. Stonemason Roger Hopkins, teamed with archaeologist Mark Lehner and a NOVA film crew, set out to solve a 3,500-year-old puzzle: how did the Egyptians raise their towering obelisks without modern machines? With a 25-ton granite slab, they pulled it off using ropes, sand, and raw muscle, offering a glimpse into the ingenuity that built Egypt’s iconic monuments. Their success leaned on old ideas made new, echoing theories from a century ago.

Chasing an Ancient Secret

Egypt’s obelisks have stood as marvels for millennia, from the 68-ton pair erected at Luxor apx. 1250 BCE, of which only one still stands. The other was gifted to France in 1831 by Muhammad Ali Pasha and moved to the Place de la Concorde. To the 455-ton giant now in Rome’s Lateran Basilica. Which was erected around 1500 BCE at Karnak’s Great Temple of Amun until the Roman emperor Constantius II ordered its removal in 357 CE.

Scholars have long debated the methods for setting these behemoths in place: ramps, levers, or sheer manpower. Hopkins, a sculptor with stone in his blood, and Lehner, a Giza researcher, wanted piece together the puzzle. Their 1999 experiment, captured for NOVA’s “Obelisk” episode, aimed to recreate Egyptian techniques. After practicing on smaller lifts earlier that year, with wooden rigging on a 2-ton, which failed, then a 9-ton obelisk with sand that succeeded, they targeted the 25-ton slab by August.

Echoes of Engelbach

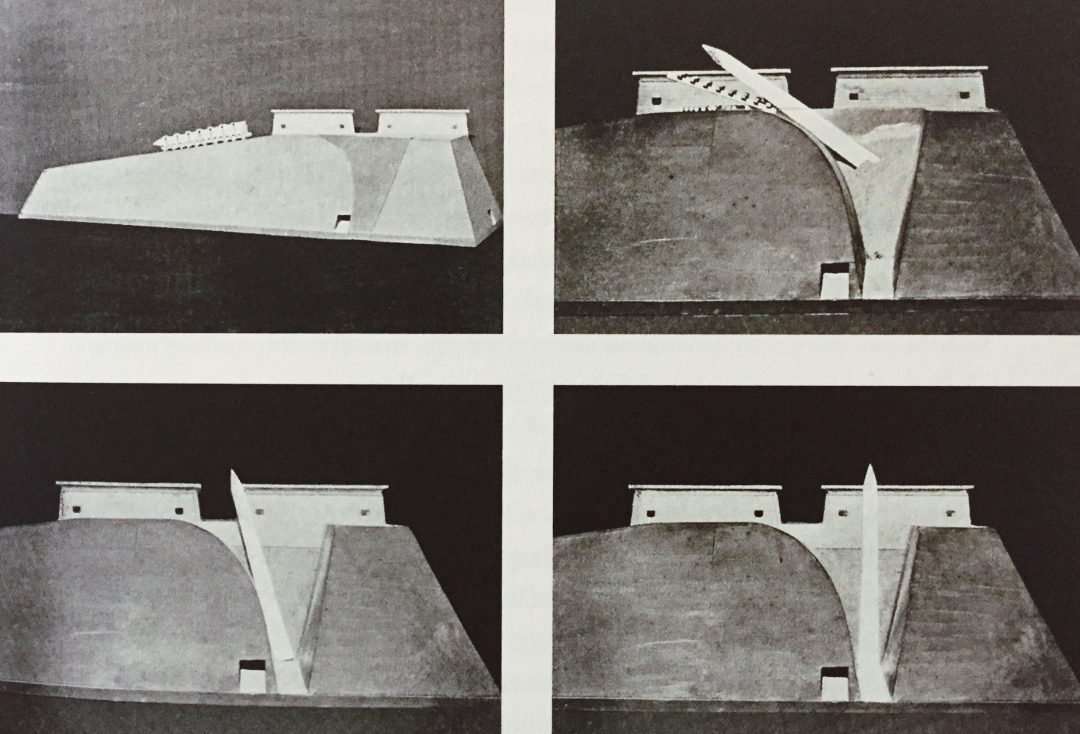

Their method built on a concept from Reginald Engelbach’s 1923 book, “The Problem of the Obelisks“. Engelbach, an Egyptologist-engineer, proposed that the ancients lowered obelisks into sand-filled pits, tilting them upright with ropes as sand was removed it would land on its pedestal. But the monolith could not just rest on its pedestal, there had to be pivot groove, or it would slide. Something Engelbach and Lehner both noted from their observations in Egypt.

Improving on the concept

Hopkins and Lehner refined this approach by adding a braking system at the ramp’s top. This was a key advancement of Engelbach’s idea. It mitigated the need for manpower and ropes to fully control the decent and eliminated a potential free fall accident. Workers laid the obelisk flat on the ramp and raised its tip, positioning the base over the pit. They lowered it onto a sand mound and gradually dug out the sand beneath. As the stone sank, they released the brake bit by bit, using ropes and manpower to guide it into position.

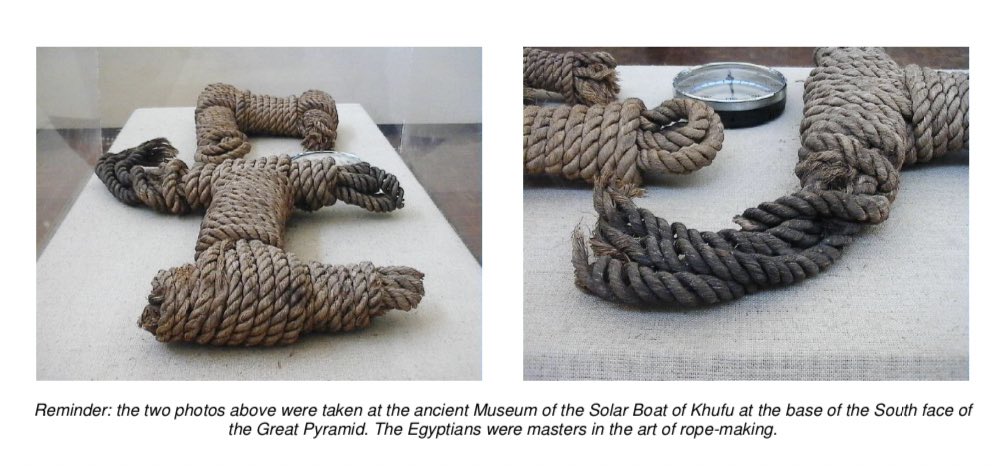

Some scoff at the idea of ropes, but Egypt’s rope-making technology exceeded expectations. The Grand Egyptian Museum preserves sturdy cords—over an inch wide—made from halfa grass and papyrus. Excavators retrieved them from Khufu’s solar barge tomb. Twisted into multi-strand cables, they lashed the 43-meter ship together, strong enough to hold tons of tension.

Hopkins’ team relied on similar strength: three crews of 40 to 50 pulled the ropes, one lifting the tip, two steadying the sides, while others scooped sand below by hand. Hopkins called the shots, Lehner tracked the positioning. On September 1st, after days of sweat, the slab locked into the groove and was then pulled upright and firm. The breaking mechanism smoothed out Engelbach’s pit decent, & ropes made the controlled placement & eventual pivot achievable.

Manpower the Ancient’s Machinery

Scale matters too Adolf Erman’s “Life in Ancient Egypt” (1894) offers a clue from Pharaoh Necho I, who quarried an obelisk at Syene, then sent 4,000 soldiers to the Hammamat quarries. Erman doesn’t confirm they raised it, but the numbers suggest muscle in reserve, thousands strong for Egypt’s giants like Karnak’s 328-ton obelisks. Hopkins’ 130 crew was a fraction, yet it hints at the ancients’ playbook: swarm a stone with bodies, and it moves.

Piecing Together the Clues

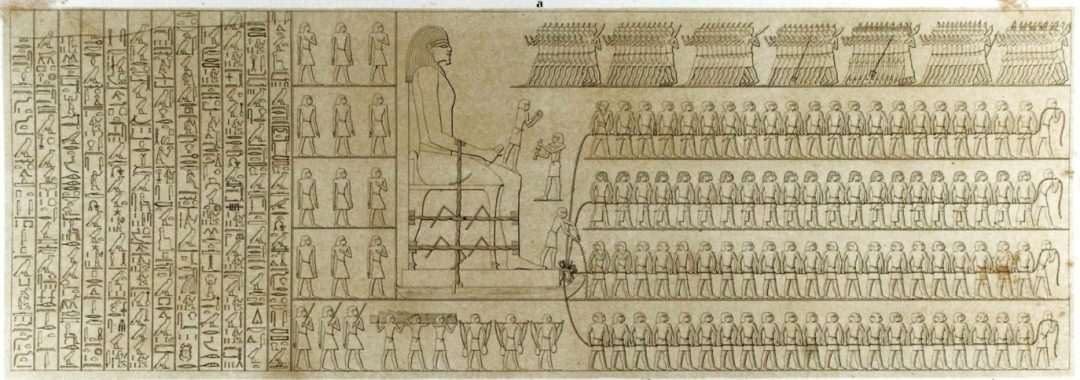

Engelbach’s pit-and-sand idea was the foundation, expounded upon by the 1999 lift, with a braking mechanism as the clincher. Egypt’s bigger obelisks likely demanded longer ramps and deeper pits. A wall painting from Djehutihotep’s tomb at Deir el-Bersha shows 172 men hauling a 60-ton alabaster statue on a sled, a 12th Dynasty effort emphasizing the scale of labor involved in moving massive stone objects. If 130 (in the case of the obelisk) can move 25 tons, 4,000 ancients could tackle 750 tons. It’s a piece, not the whole puzzle, but it was replicated successfully.

A Stone Legacy

The obelisk raised in the quarry was a quiet nod to Egypt’s builders. NOVA’s footage keeps it alive online. Hopkins and Lehner didn’t just move stone. They revived a craft, proving the ancients thrived on natures immutable physics, no hi-tech required.