From 1200 to 1470 CE, the Chimú civilization rose in Peru’s northern desert, forging Chan Chan, the largest adobe city in the Americas. Nestled near modern Trujillo, this sprawling citadel became their epicenter, a marvel of mud and ingenuity that housed thousands and stood as a testament to their dominance long before the Inca arrived. Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Chan Chan reveals a society of builders, artists, and rulers who turned a barren coast into a thriving empire, leaving a mark that time struggles to erase.

Chimu’ People a Brief History

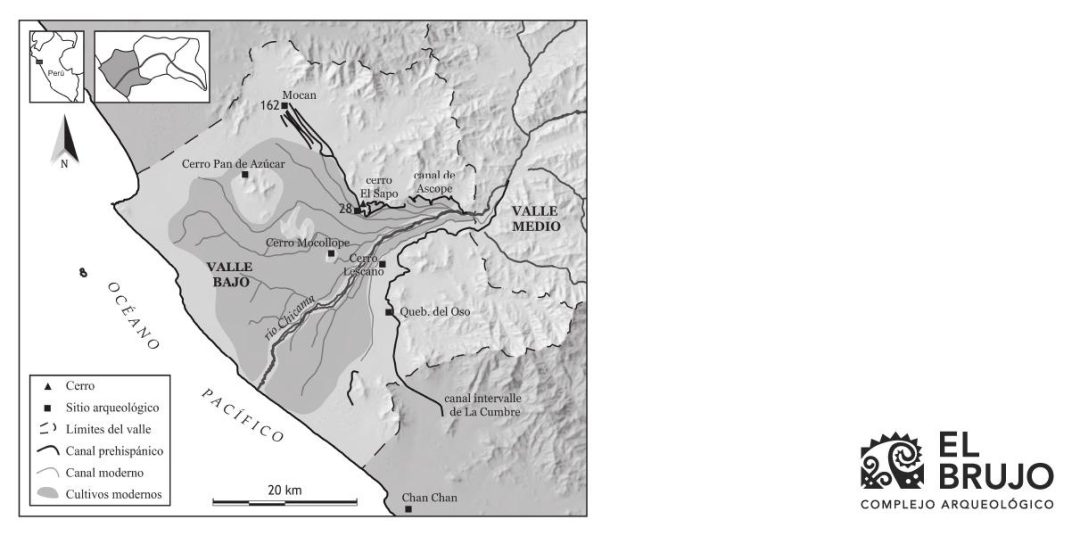

The Chimú emerged around 1200 CE in the Moche Valley, building on the ashes of the Mocha civilization, which dazzled with gold and pyramids from 100 to 800 CE. Eventually they grew into the continent’s largest pre-Incan state, spanning 600 miles of coastline from the Gulf of Guayaquil to the Chancay Valley. Their strength lay in water control. In a land parched by relentless sun, they engineered canals stretching over 50 miles from Andean rivers, irrigating fields of maize, cotton, and peanuts. This network sustained a population estimated between 30,000 and 60,000 at Chan Chan’s peak, transforming desert into abundance.

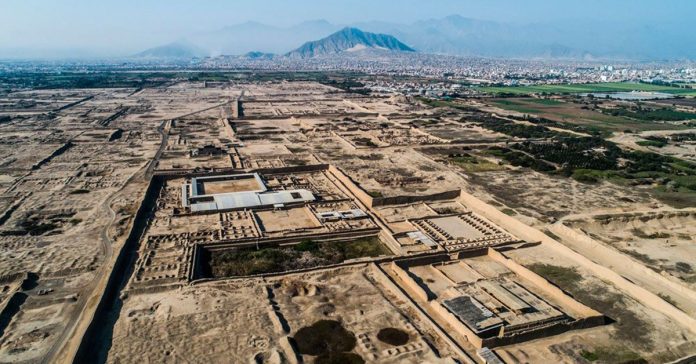

The Chimu’ Capital

Enter Chan Chan through its northern gate, and a maze unfolds. Eight citadels define its core: Chayhuac, Uhle, Tello, Laberinto, Gran Chimú, Velarde, Bandelier, Rivero, and Tschudi. Each forms a self-contained city, surrounded by towering adobe walls reaching 30 feet high with bases 16 feet thick. Inside, rulers governed from palaces crafted of mud and straw. Their plazas and corridors weaving a labyrinth once bustling with life. Beyond these elite zones, 30 smaller compounds sheltered lesser nobles. Complete with wells, patios, and reservoirs, a layout reflecting a society meticulously planned.

This city designed with purpose. The northern entrance leads to a central plaza, where hallways twist and turn, guiding traders, priests, and workers through daily routines. Each citadel belonged to a ruler who built his own seat of power, a tradition stacking generation upon generation. Archaeologists see this as evidence of centralized control, with Chan Chan serving as both capital and symbol of Chimú might.

A Structural Built for Status

Status shaped Chan Chan, high rulers, revered as divine, occupied the city’s heart. Their palaces flanked by huacas, sacred shrines where elites were buried with gold and retainers. Lesser nobles lived in those outer compounds, overseeing agriculture, crafts, and tribute: cotton cloth and dried fish sent inland. Commoners, likely farmers and fishers, dwelled outside the walls in cane huts, now faded to dust. This stratified world leaned on labor; thousands kept the canals flowing, the forges alight, and the fields green, a machine oiled by hierarchy.

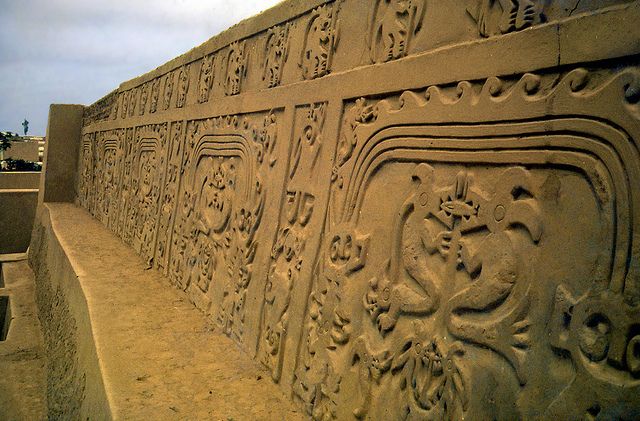

Artistic Flair

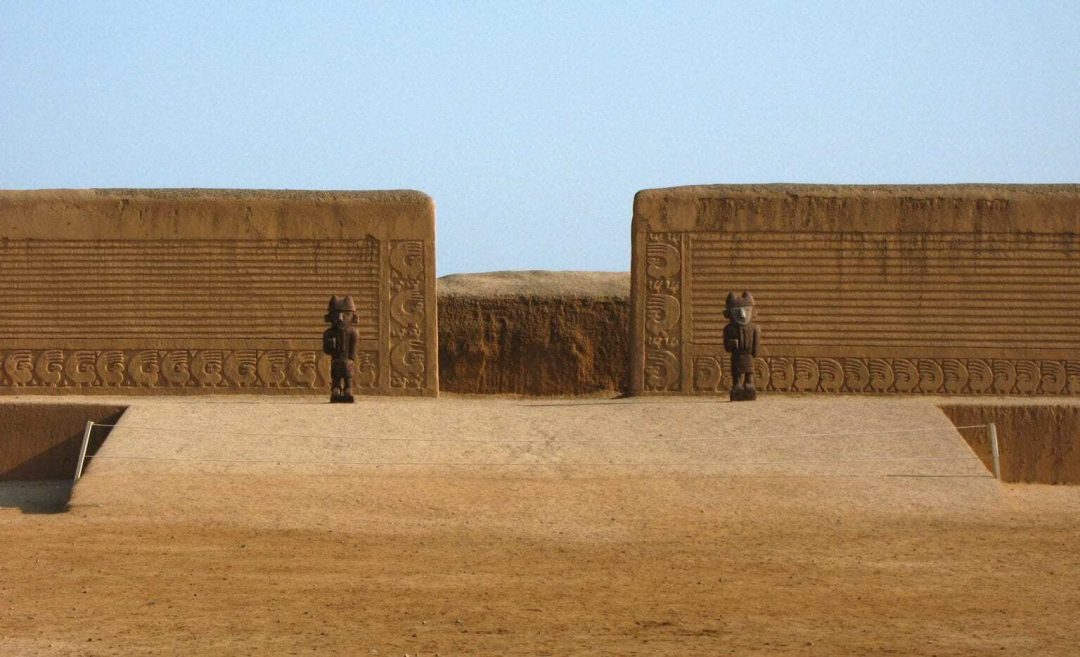

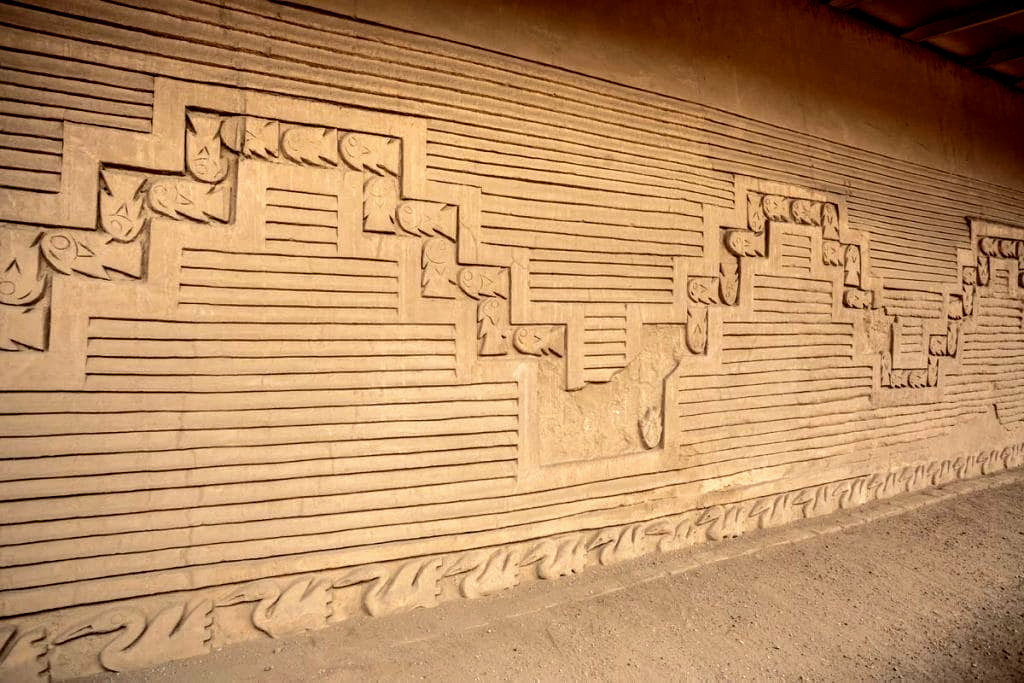

Beauty thrived alongside function. Wide patios open to walls etched with friezes: fish swim in dual directions, mirroring the Humboldt Current south and El Niño north, joined by waves, nets, and pelicans. These carvings celebrate the Pacific, a lifeline for fisheries and trade that fueled Chimú wealth. Their skill stretched beyond adobe. Metallurgists shaped gold, silver, and copper into masks, earspools, and ceremonial knives. While potters fired sleek black ceramics prized across the region. Patios doubled as stages for rituals, filled with coca leaves and chicha beer, binding the people to their gods and each other.

Ultimate Demise

Chan Chan reigned until 1470 CE, when the Inca emperor Tupac Yupanqui struck. The Chimú fell swiftly, overwhelmed by Inca numbers & strategy. Their final king, Minchancaman, was reportedly dragged to Cusco, his city annexed but not razed. The Inca admired its scale, adding stone platforms to the adobe, yet its essence lingered. After conquest, Spanish looters and El Niño rains battered the walls, but Chan Chan held firm, a ghost of its former roar.