Introduction

The notion of a global flood echoes through the annals of human history, woven into the fabric of countless cultures, religious traditions, and scientific investigations. This recurring theme suggests a shared memory of a cataclysmic event that reshaped the Earth and its inhabitants. Around 6000 years ago, circa 4000 BC. A series of catastrophic events likely transformed landscapes and societies, leaving a lasting imprint. This article explores how geological evidence, worldwide flood narratives, and the biblical story of Noah’s Flood converge to describe a singular, devastating deluge that altered the course of human civilization.

The 4000 BC Catastrophe: A Comet-Driven Deluge

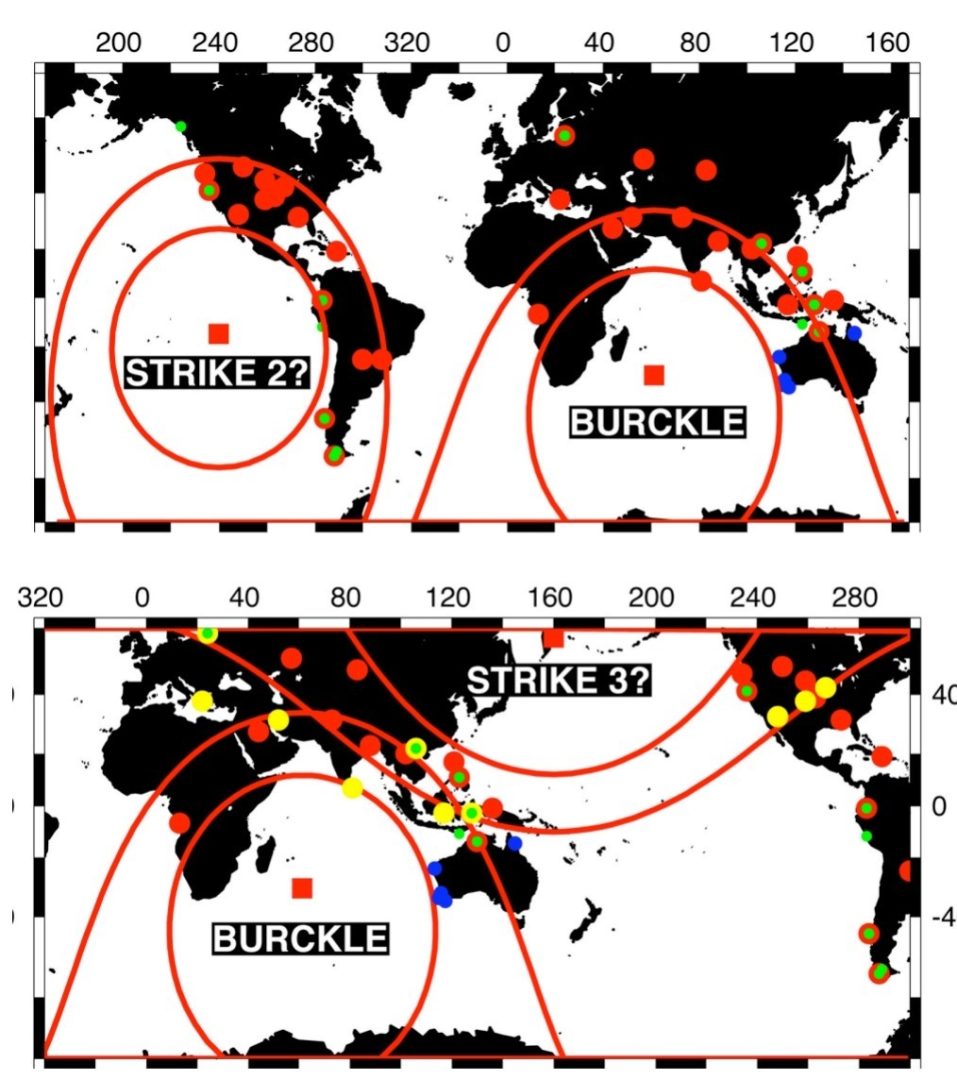

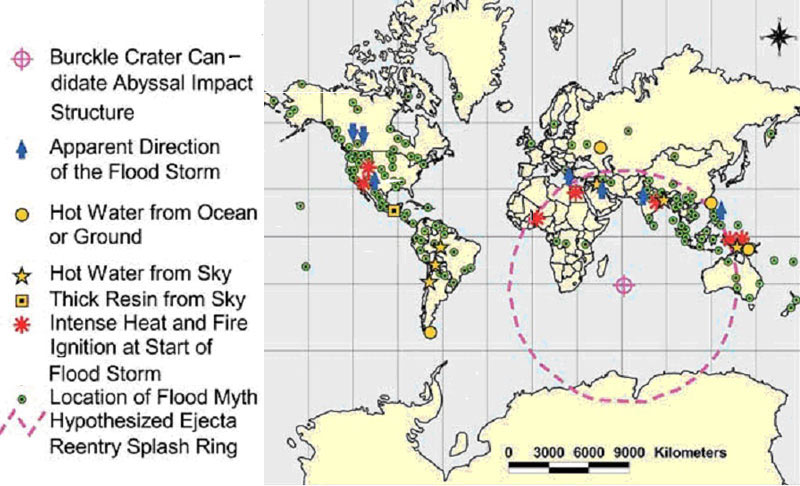

Around 4000 BC, a fragmented comet may have collided with Earth, creating multiple impact craters that unleashed profound environmental changes. One such feature, a 29-kilometer-wide crater in the Indian Ocean, points to an impactor ranging from 0.5 to several kilometres in diameter. The immense energy released vaporized millions of tons of seawater, triggering megatsunamis and days of torrential rainfall. In Western Australia, chevron deposits stretching 4 kilometers inland and rising 150 meters above sea level testify to the scale of these tsunamis. Other potential craters in the Northwest Pacific, Central-Eastern Pacific, and off Portugal’s coast suggest a global event. These impacts, occurring within a narrow time frame, likely produced tsunamis exceeding 300 meters in height in some regions, followed by prolonged rainfall as vaporized water condensed. Ancient accounts from India, the Congo, and New Guinea describe “hot rain” and “fiery particles” falling from the sky, aligning with this scenario.

Known Evidences for this 4000BC Event

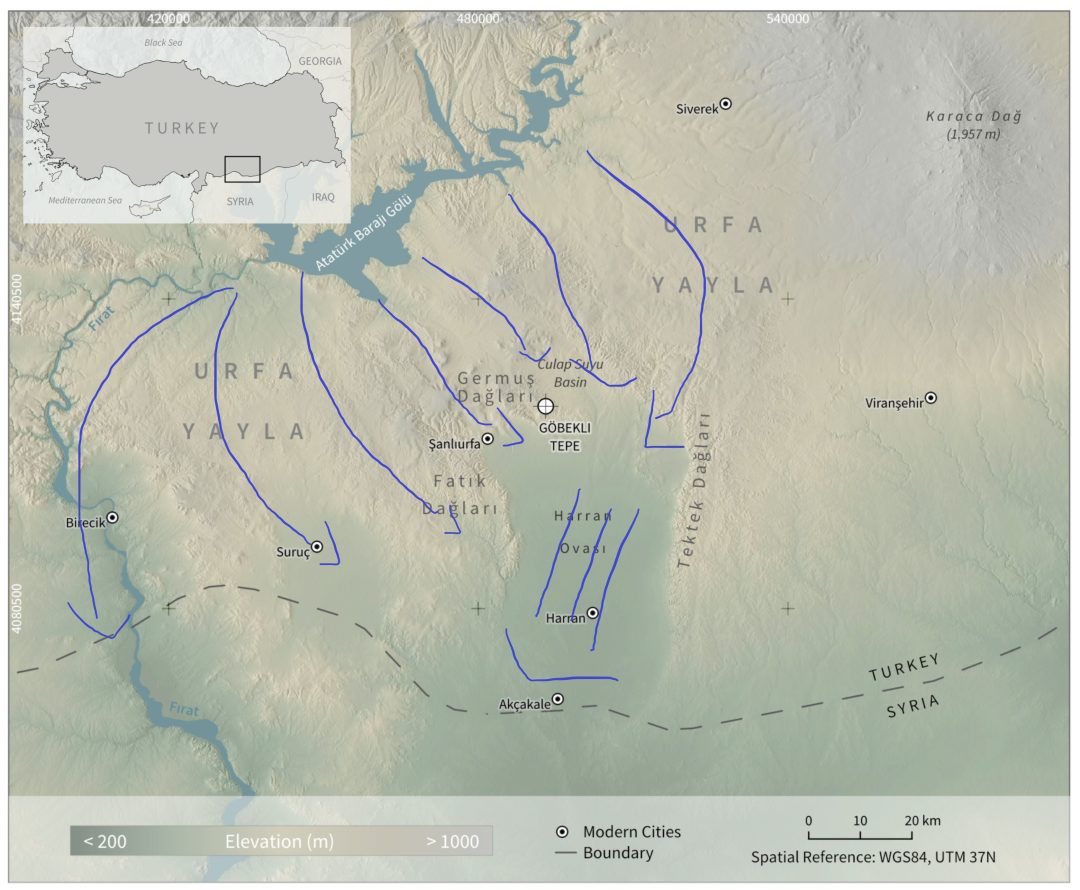

In the Iberian Peninsula, vast flood plains in the Tagus basin reveal sediment deposits 130 meters above current sea level, unexplained by glacial meltwater sources. These likely resulted from tsunamis and heavy rains tied to an offshore impact. In Northern Europe, the submersion of Doggerland, once linking Britain to the continent, may have stemmed from a tsunami breaching an ice dam, rather than gradual flooding. On the other hand, in Turkey, a lake overflow buried Göbekli Tepe under silt, as hydrological markers indicate, not human effort.

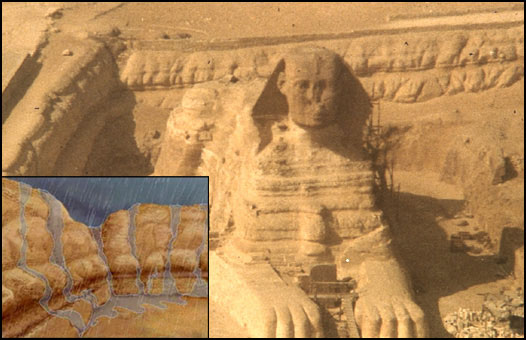

In Egypt, deep erosion on the Giza Plateau’s Sphinx enclosure suggests massive water flows, possibly damaging the monument’s head. In Western Africa, flooding of a circular geological structure forced survivors to the Atlas Mountains, leaving salt deposits from evaporated seawater. Globally, a sand-like scar crossing continents from west to east covers nearly 20% of Earth’s surface, hinting at impact ejecta. Archaeological records from this period show population declines, shifts to highland settlements, and fortified structures, marking a transition from open, agrarian communities to defensive ones.

Flood Myths: A Shared Human Memory

Over 400 flood myths span every continent, sharing remarkable similarities that suggest a collective memory of a catastrophic event. In Europe, Greek tales recount Zeus flooding the Bronze Age world, with Deucalion and Pyrrha surviving on Parnassus. Near Eastern stories, like the Hebrew account of Noah, depict divine judgment and salvation through an ark. African narratives from the Kikuyu and Yoruba speak of torrential rains and tsunamis, while Asian stories from India and China mention fiery skies and submerged lands. Australian and Pacific Island accounts describe seas sweeping inland, and Native American tales, such as those of the Cherokee and Hopi, portray survivors fleeing to mountains.

These stories often describe floods striking abruptly, frequently after celestial signs like comets or eclipses, leading to near-total loss of life, with only a few enduring on arks, rafts, or high ground. They recount environmental chaos, with hurricane winds, hot rain, and altered landscapes, mirroring geological findings. Post-flood, cultures focus on survival, birthing new social orders and technologies, such as metal weapons, indicating a profound societal shift. This uniformity across isolated cultures points to a shared event, not localized floods exaggerated over generations.

In the Greek myth from around 1500 BC, Deucalion’s ark lands on Parnassus after nine days, with survivors repopulating by throwing stones that become humans, echoing post-flood rebuilding on highlands. In Southern India, a Tamil narrative describes the sea rising against Madurai, halting near a shrine 100 plus meters above sea level, consistent with tsunami funnelling in the Gulf of Mannar. Meanwhile in Australia’s Arnhem Land, stories of tsunamis sweeping inland match chevron deposits from an Indian Ocean impact. The Cherokee of the Great Lakes region recount a flood submerging lowlands, with survivors escaping to mountains, reflecting global highland retreats.

Biblical Narrative: Noah’s Flood

The book of Genesis, in Chapters 6 through 8, describes a global flood in Noah’s 600th year, dated by some chronologies to around 2300 BC, though possibly earlier. The “fountains of the great deep” burst open, and the “windows of heaven” unleash 40 days of rain, covering “all the high mountains” by about 22 feet. The waters prevail for 150 days before receding over another 220 days, allowing Noah, his family, and animals to disembark. The “fountains” may indicate tectonic disruptions or tsunamis from impacts, while the “windows” align with torrential rainfall from condensed vapour. The universal destruction described matches both myths and geological evidence of widespread flooding.

Some have suggested an atmospheric water canopy caused the flood’s rainfall, but this model faces challenges: condensation would release lethal heat, and a thick vapor layer would obscure celestial bodies, contradicting Genesis 1:14–18. A comet impact model avoids these issues, attributing rain to vaporized seawater and tsunamis to oceanic disturbances, fitting both scripture and geological observations.

Integrating the Evidence

The 4000 BC impacts provide a unifying mechanism for diverse flood narratives. Ocean craters explain myths of seas rising inland, such as those from Tamil regions and Pacific Islands. All of these align with megatsunami evidence. Days of “hot rain” in Indian and African accounts correspond to condensed vapour from impacts. Sedimentary deposits, eroded plateaus, and submerged lands like Doggerland echo stories of destroyed terrains. Archaeological changes, including lowland abandonment, fortified settlements, and metal weapons, parallel myths of post-flood upheaval. The global spread of these narratives across isolated cultures reinforces the idea of a singular event.

In Genesis, the “fountains of the great deep” could reflect impact-driven tsunamis or tectonics. On the other hand, while the “windows of heaven” match prolonged rains from vaporized water. The 40-day rain and 150-day flood duration fit the scale of multiple impacts. In addition we have the receding waters explained by post-tsunami ocean adjustments. Noah’s survival mirrors myths like Deucalion’s and Tamil shrine accounts, emphasizing a remnant enduring to rebuild.

Around 4000 BC, societies transitioned from shaman-led, open communities to warrior-led, fortified ones. This can clearly be seen in megalithic sites like Almendres, Portugal. Myths encode this trauma, with celestial omens spurring new astronomical focus in architecture. The rise of human-targeted weapons reflects a loss of pre-flood harmony. This is akin to Genesis’s depiction of pre-flood wickedness and post-flood renewal.

Countering Objections

Mainstream science, grounded in gradualist assumptions, attributes geological features to millions of years of slow processes. Thus, dismissing flood myths as allegories. The confirmed Indian Ocean crater and its ejecta challenge this view. This because it links chevrons, flood plains, and erosion to a rapid event. Some biblical scholars debate tectonic-driven flood models, but these struggle to explain global myth uniformity. An impact-driven model integrates geological markers and narrative consistency without contradicting scripture. While some date related impacts to 2800–3200 BC, archaeological shifts like population declines and highland settlements suggest 4000 BC. However, with myth-encoded astronomical data needing further analysis to refine timelines.

Future Directions

Confirming proposed craters, such as the one off Portugal, through seismic and drilling studies could validate the multi-impact theory. Cross-referencing sediment layers and savannah formation with myth locations would help map flood extents. Myths’ astronomical and seasonal details could pinpoint event timings, enriching historical reconstructions and highlighting human resilience for modern adaptation strategies. For faith communities, an impact-driven flood model strengthens biblical historicity. It brides science and scripture while underscoring shared human heritage to foster dialogue across beliefs.

Conclusion

Geological evidence, global flood myths, and the Genesis account converge on a cataclysmic event around 4000 BC. One likely driven by comet impacts. From Iberian flood plains to Göbekli Tepe’s silt. From Deucalion’s ark to Noah’s salvation, the narrative is one of devastation and rebirth. This unified model honors ancient stories. It does so by blending science and faith to illuminate our shared past. Thus urging us to learn from history’s enduring lessons.