Forged in the crucible of time, an unknown culture rises from the prehistoric mists of the Americas, its legacy etched in copper and shrouded in mystery. Thriving in the Great Lakes region, it spanned modern-day Michigan, Wisconsin, and Ontario. From approximately 4000 to 1500 BCE, this enigmatic civilization mastered copper mining and trade, leaving behind a trail of sophisticated artifacts and unanswered questions. From the copper-rich veins of the Keweenaw Peninsula to the tantalizing possibility of transatlantic connections with the ancient Greeks and Minoans, as hinted by the Greek philosopher Plato and later referenced by the historian Plutarch, this article delves deep into the heart of a lost world. It challenges conventional understanding of early human ingenuity, weaving together archaeological evidence, theoretical frameworks, and speculative links to reshape our view of prehistoric America.

A Civilization Forged in Copper

The Heart of the Great Lakes

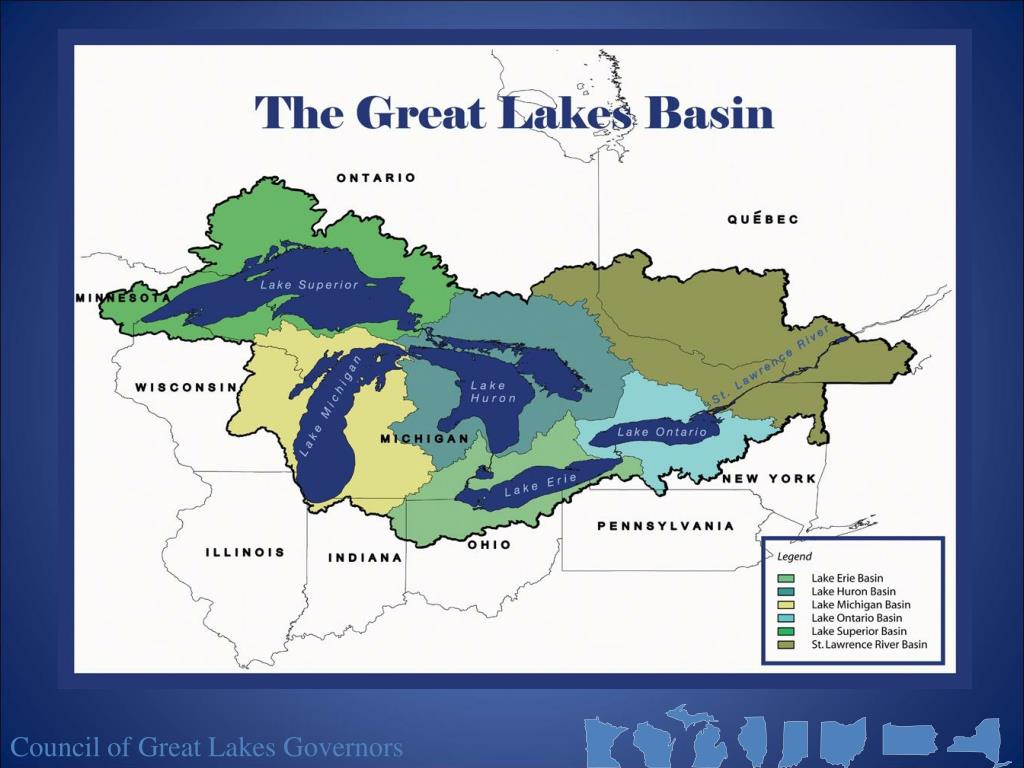

The unknown culture, later termed the Old Copper Culture, emerged as a pre-agricultural society, its people relying heavily on hunting, gathering, and fishing for sustenance across the expansive Great Lakes region. Their territory centered on copper-rich locales, notably the Keweenaw Peninsula in Michigan and Isle Royale in Lake Superior, where vast deposits of native copper lay waiting. This ancient civilization developed a remarkable expertise in extracting and processing this resource, crafting an array of tools. Tools like axes, knives, and fishhooks, along with ornamental items like copper beads and pendants. These artifacts, marked by technical precision and artistic expression, reveal a culture of extraordinary sophistication that thrived without the benefits of agriculture.

Old Copper Culture Evidence

Core Samples

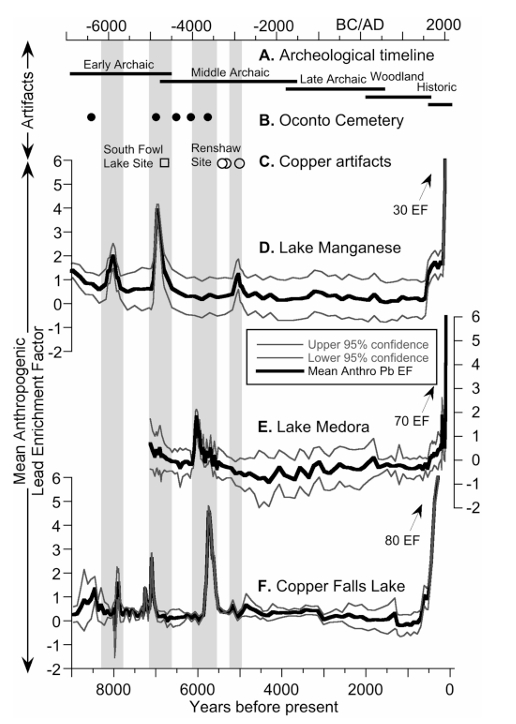

Archaeological evidence underscores the scale of their operations. Sediment cores from Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, and Lake Huron reveal a distinctive chemical signature of copper mining byproducts dating back to 9000 years ago, with a significant increase in activity between 4000 and 3000 BCE. The Old Copper Culture employed a variety of mining techniques, including open-pit mining, shaft mining, and quarrying, using rudimentary stone and wooden tools to extract the ore.

Missing Copper

This ore was then crushed and processed to produce pure copper, a process that supported an economy estimated to have processed hundreds of thousands of tons of copper over millennia. Yet, a perplexing enigma persists only a small fraction of this copper has been recovered from archaeological sites, leading to the phenomenon known as the “missing copper.” A whopping 500,000 tons of it. This discrepancy has sparked theories of extensive trade, loss due to natural processes like erosion or corrosion, or even recycling and reuse by the culture itself.

Timeline of a Thriving Culture

The chronological arc of the Old Copper Culture offers a window into its rise and fall:

- 4000 BCE: The culture emerges in the Great Lakes region, marking the onset of organized copper mining.

- 3000 BCE: Trade networks expand across the Americas, reaching a peak of complexity and geographical scope.

- 2000 BCE: The culture reaches its zenith, showcasing advanced metallurgy and an extensive trade network that connected distant regions.

- 1500 BCE: A sudden decline halts mining and trade activities, signaling the end of this thriving civilization.

Key Sites and Artifacts

Several key sites and artifacts illuminate the Old Copper Culture’s legacy:

- Keweenaw Peninsula: A copper-rich region in Michigan, extensively mined and later abandoned around 1500 BCE, reflecting the culture’s sudden cessation.

- Isle Royale: A copper-rich island in Lake Superior, where archaeological evidence points to significant mining activities by the Old Copper Culture.

- Copper Harbor: A Michigan site featuring extensive copper mining and smelting operations, which abruptly ceased around 1500 BCE, leaving behind traces of their advanced techniques.

- Artifacts: Distinctive copper axes, knives, beads, and pendants, widely traded across the Americas, disappear from the archaeological record post-1500 BCE, adding to the mystery of their decline.

The Enigma of Identity

The exact identity of the Old Copper Culture’s people remains a topic of intense debate among archaeologists and anthropologists. Several theoretical frameworks have been proposed to explain their origins and cultural affiliations:

Identity Hypotheses

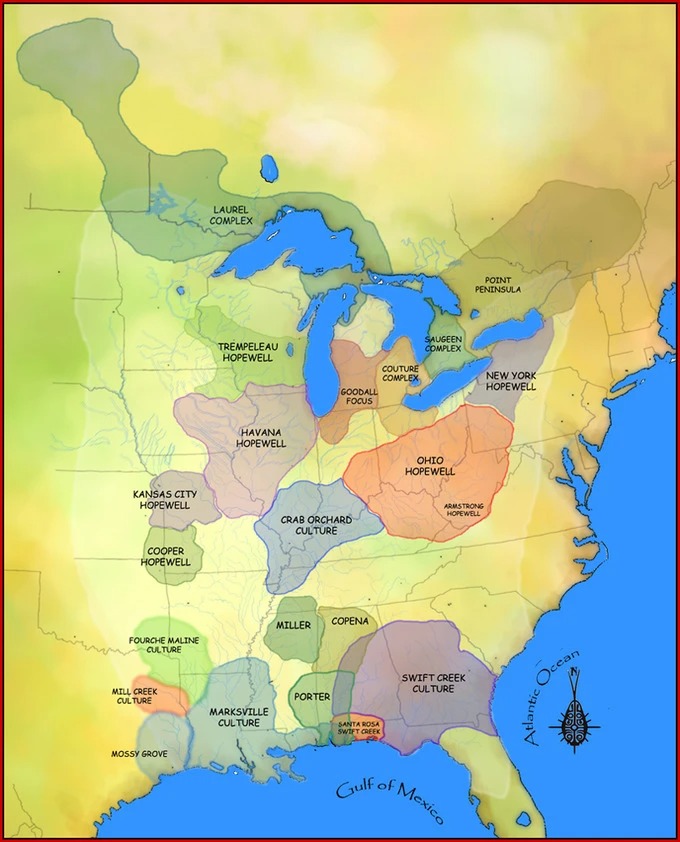

- The “Archaic” Hypothesis: Suggests the Old Copper Culture evolved from the Archaic culture (8000–1000 BCE), a prehistoric period in the Eastern Woodlands characterized by a mobile hunter-gatherer lifestyle. This period, marked by warmer and drier climates, saw the development of stone tools, simple shelters, and a rich spiritual life focused on animism and shamanism. The transition to copper technology around 4000 BCE likely built on these foundations.

- The “Woodland” Hypothesis: Proposes that the Old Copper Culture was a precursor to the Woodland culture (1000 BCE–1000 CE), which adopted sedentary lifestyles and agriculture, including the cultivation of maize, beans, and squash. The Woodland’s pottery tradition and complex social organizations may have inherited elements from the Old Copper Culture’s trade networks.

- The “Paleoindian” Hypothesis: Posits a connection to the Paleoindian culture (15,000–8000 BCE), one of the earliest human populations in the Americas. Known for big game hunting of mammoths and mastodons, their mobile lifestyle and tool technologies may have influenced the Old Copper Culture’s resource-driven society.

Old Copper Culture Identity

Linguistic Clues

Linguistic and cultural clues provide additional insights. Some researchers suggest the Old Copper Culture may have spoken a language from the Algonquian family, still used by Indigenous communities like the Ojibwe and Haudenosaunee in the Great Lakes region. Cultural practices, such as copper mining and trading, mirror those of these modern groups, suggesting a deep historical continuity.

Genetics

Genetic studies further illuminate their origins. A 2016 mitochondrial DNA analysis published in Science Advances. And a 2021 ancient DNA study in Nature examined human remains from Old Copper Culture sites. Both found genetic links to modern Indigenous communities in the Great Lakes and ancient Paleoindian populations. Reinforcing the idea of a long-standing presence in the region. However, these findings are preliminary, and more research is needed to fully unravel their identity.

A Vast and Complex Trade Network

The Old Copper Culture’s copper trade networks extended far beyond their local territory. Encompassing a vast region that included the eastern United States, the Great Plains, and Mesoamerica. Archaeological discoveries have unearthed copper artifacts from the Old Copper Culture in diverse locations:

The Americas

- The Eastern United States: Notably in the Ohio River Valley and the Appalachian Mountains, where trade goods suggest robust exchange routes.

- The Great Plains: Including present-day Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma, where copper items indicate long-distance commerce.

- Mesoamerica: Particularly in modern-day Mexico and Guatemala, hinting at connections with advanced civilizations to the south.

These findings point to an extensive and complex trade system, potentially spanning thousands of miles. The “missing copper” phenomenon, where only a small percentage of the estimated extracted copper is accounted for, supports the theory of significant exportation. Researchers speculate that this copper may have been traded to distant cultures. Then recycled into new artifacts, or lost to natural degradation, though the exact fate remains elusive.

To estimate the extent of copper extraction, archaeologists have employed methods such as excavations at mining sites. Geochemical analysis of ore deposits, and historical records from European colonizers. These efforts highlight the culture’s economic prowess but also underscore the challenges in tracing their full impact.

The Sudden and Mysterious Fall

Around 1500 BCE, the Old Copper Culture abruptly ceased. Marking the end of a civilization that had endured for over 2,500 years. The reasons for this decline are still debated, with several factors potentially contributing:

- Climate Change: Shifts in weather patterns may have reduced the availability of food resources, destabilizing the population and economy.

- Resource Depletion: The intensive copper mining and trade activities might have exhausted local deposits, making sustenance difficult.

- Conflict and Warfare: Encounters with rival groups could have weakened the culture, leading to its collapse.

- Disease and Epidemics: The introduction of new diseases may have decimated the population, a theory supported by the sudden nature of the decline.

The timeline of this decline offers further context:

- 1200 BCE: The Terminal phase of the Old Copper culture begins in the Great Lakes region, ushering in a new cultural phase.

- 1000 BCE: The Old Copper Culture begins to wane, marking a period of transformation in the region.

Key sites associated with this decline, such as Copper Harbor and the Keweenaw Peninsula. Show signs of abrupt abandonment, while artifacts like copper axes and beads vanish from the record, deepening the mystery.

Echoes Across the Atlantic? A Speculative Link

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Old Copper Culture is the possibility of transatlantic connections with the ancient Greeks and Minoans. A hypothesis inspired by Plato’s accounts of Atlantis. In his dialogues Timaeus and Critias (c. 360 BCE), Plato describes a mythical island beyond the Pillars of Hercules (the Strait of Gibraltar), inhabited by the Atlanteans. A civilization renowned for its vast copper wealth used in elaborate temples. This narrative intrigued later thinkers, including Johannes Kepler. Who in his 1593 Mysterium Cosmographicum speculated on ancient trade between the Old and New Worlds based on Plato’s works.

A 2016 paper, “Travelling from Canada to Carthage in 86 AD,” presented at the Ancient Greece and the Modern World Conference, expands on this idea. The author suggests Plato’s copper-rich Atlanteans may reflect real trade with the Americas, particularly the copper-rich Great Lakes region. Evidence includes:

- Copper Artifacts: Similarities in design and craftsmanship between Old Copper Culture artifacts and those found in Mediterranean sites like Delphi.

- Isotopic Analysis: Copper from both regions shares isotopic signatures, hinting at a common source.

- Maritime Capability: The Greeks’ and Minoans’ advanced maritime networks could have extended across the Atlantic.

Plutarch’s De Facie in Orbe Lunae (c. 100 CE) describes a sea voyage northwest past the Pillars of Hercules, aligning with the North Atlantic’s geography—potentially reaching Iceland, Greenland, or Nova Scotia. Astronomical correlations, such as lunar eclipse timings and the use of Ursa Major for navigation, support this route. While pre-Columbian transatlantic contact remains controversial, these clues suggest a feasible, if speculative, link warranting further investigation.

New Scientific Evidence: Ötzi Ice Man’s Axe

New scientific analysis brought to us By Rick Osmon has provided compelling evidence. Suggesting that the copper axe of Ötzi the Iceman, a 5,300-year-old mummy discovered in the Alps, may have originated from the Keweenaw Peninsula or Isle Royale in Upper Michigan. Conducted by Heartland Research Inc. in collaboration with ALS Scandinavia AB and Lehigh University’s Whitaker Laboratory. The study compared the axe’s composition to native Michigan copper, which boasts a purity exceeding 99.9%. Key findings include the presence of trace mercury (1500-1900 ppb).

In Michigan copper samples, a geological anomaly not typically found in Old World smelting products, mirroring Ötzi’s axe. Which lacks this mercury but aligns in purity (>99.3%) and trace element profiles. Isotopic analysis and mass spectroscopy data from Luleå Technical University further revealed similarities. With an AI statistical comparison concluding a high likelihood of Michigan sourcing. This evidence, pending authentication from Lehigh’s electron-beam microscopes, supports the hypothesis of transatlantic copper trade during the Bronze Age. Challenging traditional archaeological timelines.

A Legacy Rediscovered

The Old Copper Culture reshapes our understanding of ancient America, predating agriculture with a mastery that rivaled Old World innovations. Their extensive trade networks and possible transatlantic ties challenge conventional timelines, positioning them as pioneers of human achievement. As research continues, through sediment analysis, genetic studies, and new excavations, the story of this lost civilization unfolds. Their copper legacy, etched in tools and beads, and an axe, stands as a testament to resilience and ingenuity, echoing across millennia.

Original Version of this article was published in Pharos Magazine Ed. 2

Stay tuned to Ancient History X for more revelations from the edges of time.