A team of Spanish archaeologists has unraveled one of the most intriguing mysteries in Iberian prehistory: how a massive stone basin ended up inside the Matarrubilla dolmen near Seville—and why it is at least 1,000 years older than the structure meant to enshrine it.

Their findings, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, not only confirm the earliest known example of megalithic maritime transport in the Iberian Peninsula but also suggest that the Copper Age society in southern Spain was more complex and interconnected than previously believed.

A Monumental Enigma Inside a Dolmen

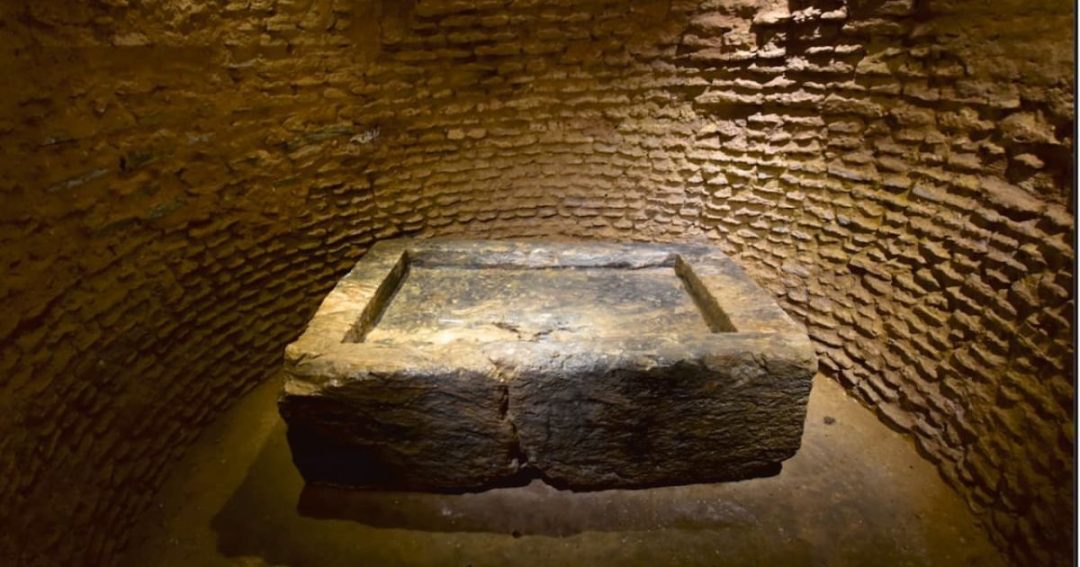

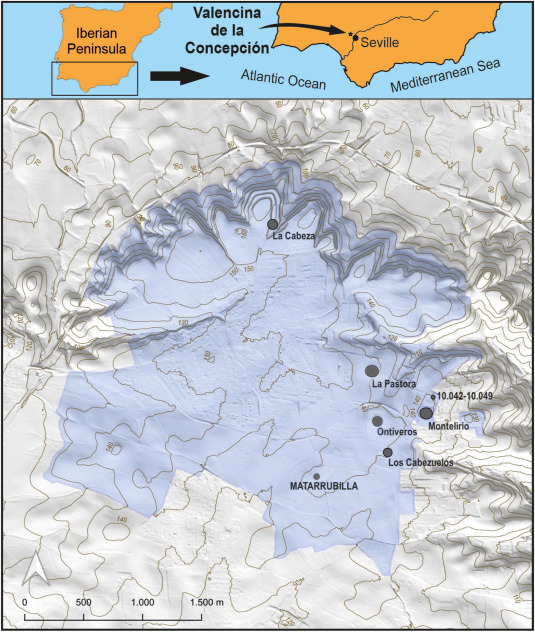

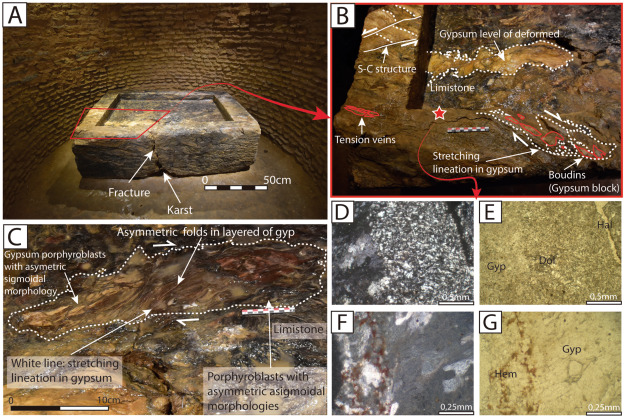

The Matarrubilla dolmen, part of the vast prehistoric site of Valencina de la Concepción in Andalusia, has long puzzled researchers due to an unusual artifact discovered inside: a rectangular stone basin measuring 1.7 m long, 1.2 m wide, and nearly 0.5 m high. Weighing more than 2,000 kg, the basin’s sheer size, unique material, and placement within the dolmen’s chamber raised numerous questions.

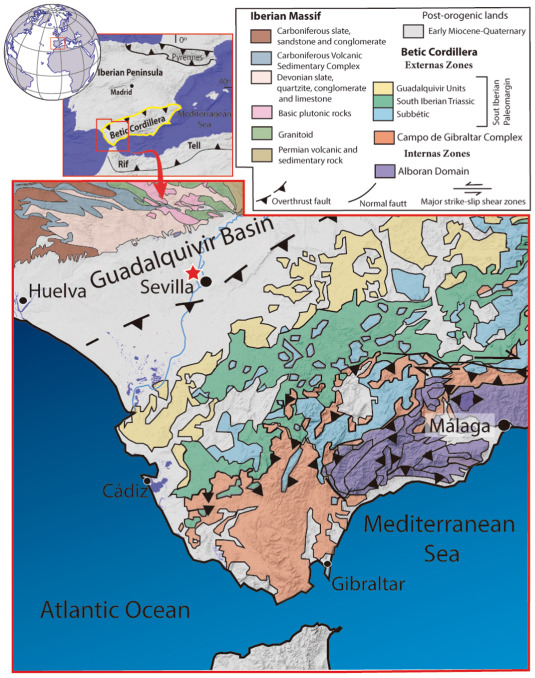

First documented in 1917, the basin seemed far too large to have been maneuvered through the dolmen’s narrow corridor. Additionally, its distinctive rock—gypsiferous cataclasite with red, green, and white veining—does not naturally occur anywhere near Valencina.

Provenance and Transport: From Distant Quarry to Ritual Center

By using geological and geoarchaeological techniques, the research team traced the stone’s likely origin to the opposite side of the ancient Gulf of Guadalquivir, near present-day Las Cabezas de San Juan, approximately 55 km from Valencina. At the time (around 3000–4500 BCE), the gulf stretched much farther inland than it does today.

Because of the stone’s weight and the distance, the team concluded that prehistoric people transported it via water—on rafts or boats—across the ancient bay. Once ashore, the basin was dragged approximately 3 km uphill, likely using wooden sleds and human or animal power.

This marks the first confirmed instance of riverine or maritime transport of a megalith in Iberian prehistory. Comparable methods have only previously been documented at sites like Stonehenge (UK) and Newgrange (Ireland).

Older Than Its Tomb: A Chronological Revelation

Using Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating—which reveals when minerals last saw sunlight—the researchers determined the basin’s placement occurred between 4544 and 3227 BCE. In contrast, they dated the construction of the Matarrubilla dolmen to between 2700 and 2400 BCE.

This staggering 800–1,800-year gap suggests that the basin already served a sacred or symbolic role long before the dolmen emerged. Researchers suggest it may have originally belonged to an earlier, undocumented monument on the same site—later incorporated into the dolmen during its construction.

Crafted Without Metal Tools

Contrary to earlier assumptions that the basin might have been cut using copper implements, the team’s microscopic analysis revealed a different story. The tool marks on the stone are consistent with polished stone axes and adzes, not metal. These marks closely resemble those left on wood by similar tools, indicating sophisticated craftsmanship with available Neolithic technology.

The shaping was done on all sides, further supporting the theory that the basin was carved before being placed inside the dolmen, and not afterward.

Symbolism in Stone: Aesthetic and Ritual Significance

The choice of this specific type of rock—a vibrant, multicolored gypsiferous cataclasite—is unlikely to be accidental. With its striking red, green, and white veins, the stone likely held strong symbolic or aesthetic appeal. Its presence may have marked a spiritual focal point or status object, reflecting social hierarchy, ceremonial function, or cosmological meaning.

The stone’s exotic origin and deliberate transport to Valencina suggest that the site served as a major ceremonial and trade hub during the Copper Age. The basin’s uniqueness—there are no known parallels on the Iberian Peninsula, and only distant comparisons in Ireland and Malta—emphasizes its exceptional value.

Rethinking Iberian Prehistory

This discovery challenges long-standing assumptions about the capabilities of Iberian prehistoric societies. It demonstrates that Neolithic and Copper Age communities in southern Spain:

- Had the technical knowledge to carve and transport massive stones

- Were able to coordinate long-distance projects and resource acquisition

- Possibly possessed boats capable of bearing several tons of weight

- Valued aesthetic and symbolic objects to an extent previously underestimated

The study reinforces Valencina’s status as one of Europe’s largest and most sophisticated Copper Age settlements—active centuries before its better-known megalithic counterparts in northern Europe.

Final Thoughts

The Matarrubilla basin reveals a highly organized and symbolically rich prehistoric world—not just as a mysterious stone relic, but as a powerful cultural artifact.

Its extraordinary journey from quarry to shrine stands as a testament to the ingenuity, planning, and cultural complexity of early Iberian societies.

As lead researcher Luis M. Cáceres Puro and colleagues conclude, this megalithic voyage across water “must have taken place between the 5th and 4th millennia BCE,” suggesting that the prehistoric people of southern Spain were already masters of both land and river.

Sources:

- Luis M. Cáceres Puro, Teodosio Donayre Romero, et al. Navigable megaliths: A geoarchaeological approach to the giant stone basin of Matarrubilla (Valencina, Spain). Journal of Archaeological Science, 2025.

- The enigma of the gigantic basin in the Matarrubilla dolmen solved. — La Brújula Verde (English version)

- Seafaring megaliths: A geoarchaeological approach to the Matarrubilla giant stone basin…” — Academia.edu / Journal Abstract