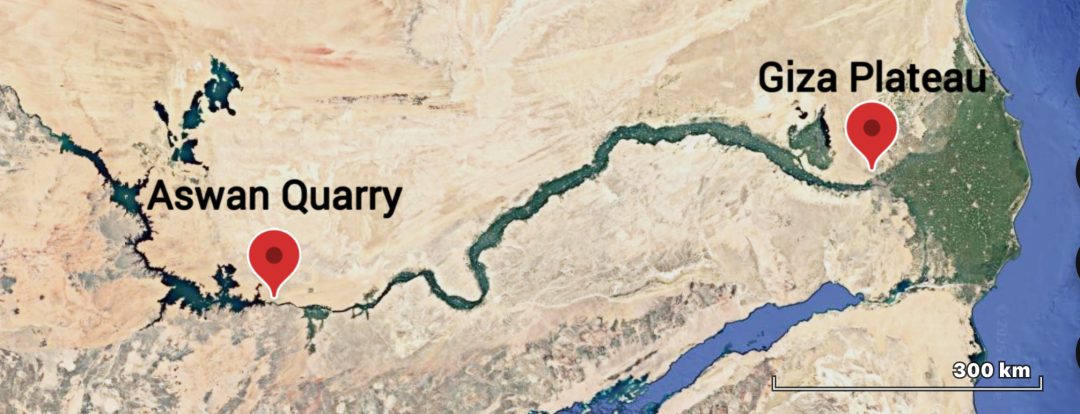

Ancient Egyptian engineering transformed bedrock into 60-ton granite blocks. Eventually placed in the King’s Chamber and relieving chambers of the Great Pyramid. Workers quarried these stones at Aswan, transported them 800 kilometers down the Nile, and installed them precisely at Giza. This article details the process, from bedrock extraction to pyramid placement. Offering geological, archaeological, and engineering evidence to support each step.

Quarrying Granite at Aswan

At Aswan, 800 kilometers south of Giza, workers targeted red granite, valued for its durability. They used two techniques, per Dieter Arnold’s Building in Egypt: Pharaonic Stone Masonry (1991). The fire-and-water method set fires on granite to create stress, then poured water to crack it along fissures. Diorite, a harder stone, was shaped into tools for pounding the fractured granite, removing material in bulk.

Additional Steps:

For refining the sides diorite pounding balls were employed. A painstaking process that took months. The unfinished obelisk at Aswan, studied by many show these diorite fingerprints, along with thousands of balls found in the historical record, confirming this method.

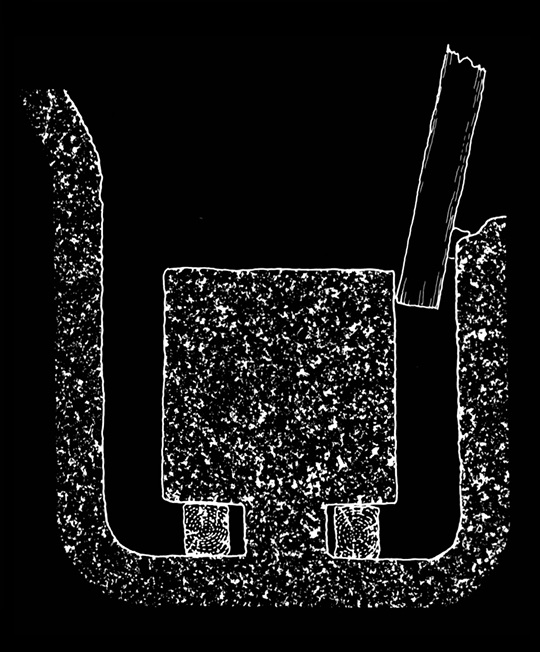

This author (expanding on Dieter Arnold’s work, left) postulates that a wooden frame would be built around the block when the rib underneath was the only portion remaining. This frame, tantamount to a sled, assisted in the removal of the block. Workers would rock the frame side to side until the rib broke, freeing it from the bedrock.

Ancient Egyptian Engineering in Extraction

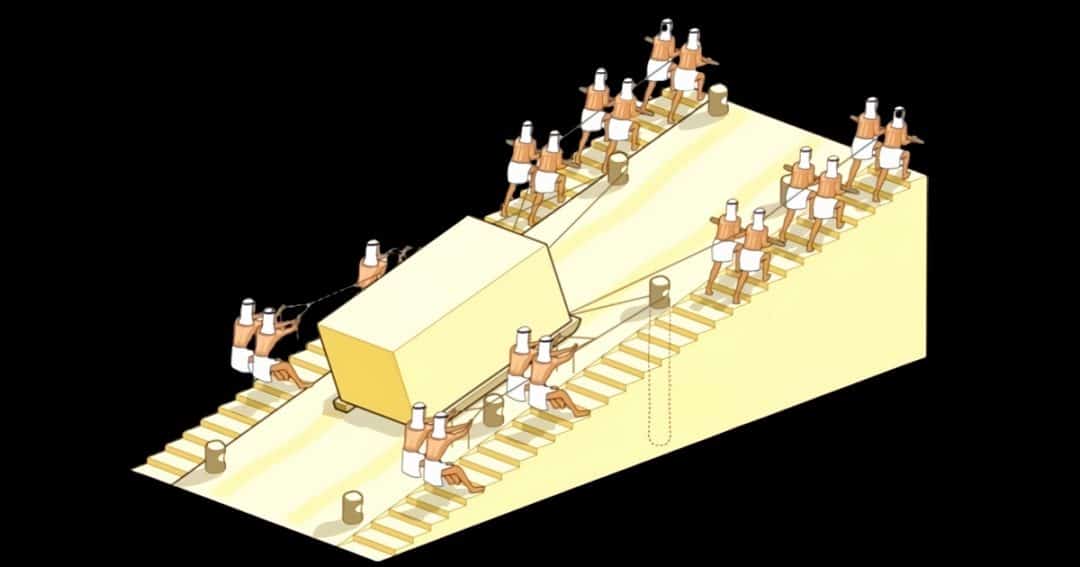

To extract blocks, workers used a ramp system, evidenced by the Hatnub quarry discovery, reported by Yannis Gourdon and Roland Enmarch (Sci.News, 2018). Hatnub, 65 kilometers southeast of Minya, revealed a 4,500-year-old quarry ramp. Its 11.3-degree slope, or 20% grade, featured staircases with postholes, anchoring wooden posts for ropes and simple pulleys. The Pulleys would act as a force multiplier assisting in the removal of the block.

After extraction about 300 workers could drag the block, strapped to a sledge in coordinated teams, to a canal near the Nile, per Aswan Quarry Project findings (Kelany et al., 2000s). The canal was pre dug ahead of the inundation season. Taking advantage of the Nile’s annual flooding, or “inundation,” seasons raising water levels.

Loading Blocks onto Barges

At the Aswan canal, workers loaded the block onto a barge. The canal utilized a sluice gate; a wooden barrier that controls water flow. Closing the gate, lowered the water, leveling the barge’s deck level with the ground. Using ropes and posts mounted to the deck, with simple pulleys, they pulled the sledge partway onto the deck. Opening the sluice gate flooded the canal, raising the barge, lifting the block’s grounded portion. Workers now with the sledge free from the ground could more easily position it on the barges wooden deck.

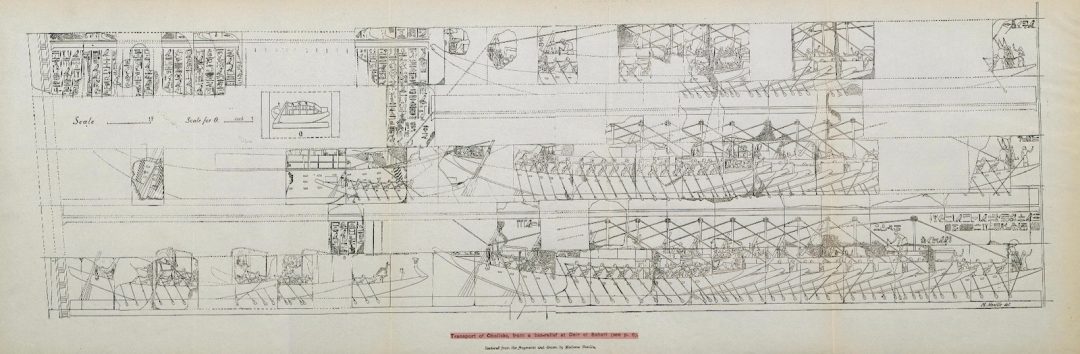

Barges in the historical record, specifically Hatshepsut’s obelisk ship, circa 1473 BCE, could carried up to 700 tons, per Chris Massey’s analysis (Engineering History and Heritage, 2009). At 200 feet long, it was towed by 20–30 rowed boats. Pierre Tallet’s dock studies (The Red Sea in Pharaonic Times, 2012) confirm canal use.

Transporting Blocks Down the Nile

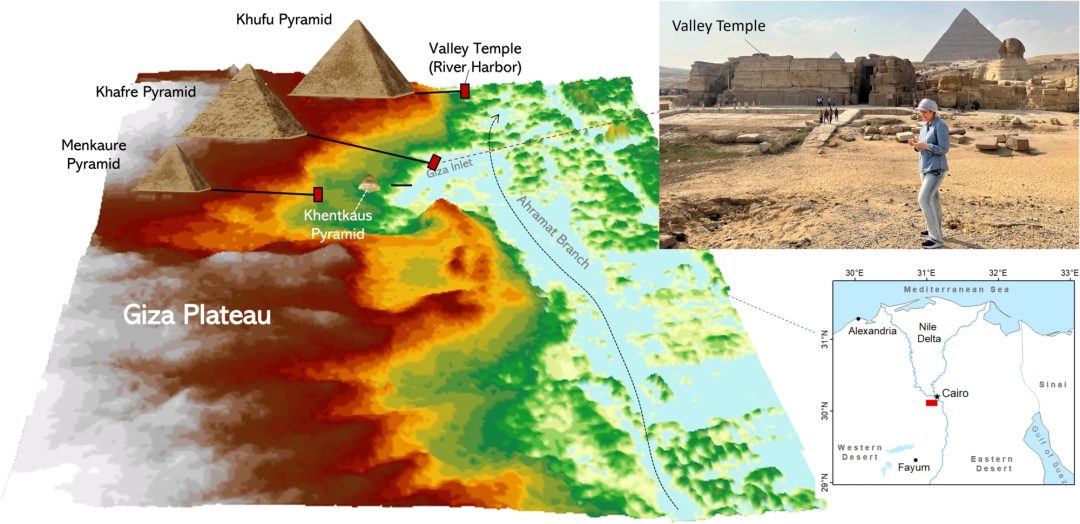

The barge sailed 800 kilometers down the Nile to Giza’s port, using the inundation’s current. A study by Eman Ghoneim and colleagues (Communications Earth & Environment, 2024) identified the Ahramat Branch, an extinct Nile channel running along the Western Desert Plateau, near Giza’s pyramids. This branch, 20 kilometers long and 0.5 kilometers wide, served as a waterway for transporting materials, with valley temples, acting as river harbors. The barge entered a canal off this branch, where workers lowered the water with a sluice gate, grounding the barge. After repositioning the block’s ends rested on the canal’s edge, ready for transport.

Ancient Egyptian Engineering in Block Movement

From the port, workers moved the block (on the sledge) to the pyramid site using an external counterweight ramp below the Giza plateau, proposed by Jean-Pierre Houdin (The Secret of the Great Pyramid, 2008). This ramp ascended from the Ahramat Branch’s harbor to the plateau. Workers strapped the sledge, linked by ropes to a counterweight sled with 60–70 tons of stones, descending an opposing ramp. With an 8-degree slope, supported by archaeological ramp evidence (Arnold, 1991), it needed 8.4 tons of force (F = m * g * sin(8°)) for a 60-ton block.

Ancient Egyptian Engineering in Installation

At the pyramid site, workers used an internal spiral ramp or an external ramp to course 43, about 50 meters high, to install blocks in the King’s Chamber and relieving chambers. Houdin’s spiral ramp, within the pyramid, allowed 90-degree turns to higher levels. This ramp rose with the pyramid allowing placement of blocks on successive levels.

Engineering Feats and Legacy

Ancient Egyptian engineering excelled in transforming granite into a monument. Fire-and-water quarrying extracted blocks efficiently. Hatnub-style ramps moved them from quarries. The Ahramat Branch enabled Nile transport, while Houdin’s counterweight ramp delivered blocks to the site. Spiral or external ramps ensured precise installation.

Compilation Hypothesis Brought to you by Author.

Sources:

- Arnold, D. (1991). Building in Egypt: Pharaonic Stone Masonry. Oxford University Press.

- Marián Marčiš, Marek Fraštia (2023) The problems of the obelisk revisited: Photogrammetric measurement of the speed of quarrying granite using dolerite pounders. Science Direct

- Breasted, J. H. (1906). Ancient Records of Egypt. University of Chicago Press.

- Bunbury, J. (2019). The Nile and Ancient Egypt: Changing Land- and Waterscapes. Cambridge University Press.

- Brier, B., & Houdin, J.-P. (2008). The Secret of the Great Pyramid. HarperCollins.

- Engelbach, R. (1923). The Problem of the Obelisks. T. Fisher Unwin.

- Ghoneim, E., et al. (2024). “The Egyptian pyramid chain was built along the now abandoned Ahramat Nile Branch.” Communications Earth & Environment, 5:233. Link.

- Gourdon, Y., & Enmarch, R. (2018). “Archaeologists Uncover 4,500-Year-Old Ramp System at Alabaster Quarry in Egypt.” Sci.News. Link.

- Kelany, A., et al. (2000s). Aswan Quarry Project Reports. Egyptian Antiquities Organization.

- Massey, C. (2009). Engineering History and Heritage. ICE Publishing.

- Tallet, P. (2012). The Red Sea in Pharaonic Times. Institute Français d’Archéologie Orientale.