In a groundbreaking study published in Nature, researchers have sequenced the first complete ancient human genome from early dynastic Egypt. This achievement offers new insight into ancestry, daily life, and cross-regional connections in Egypt over 4,500 years ago.

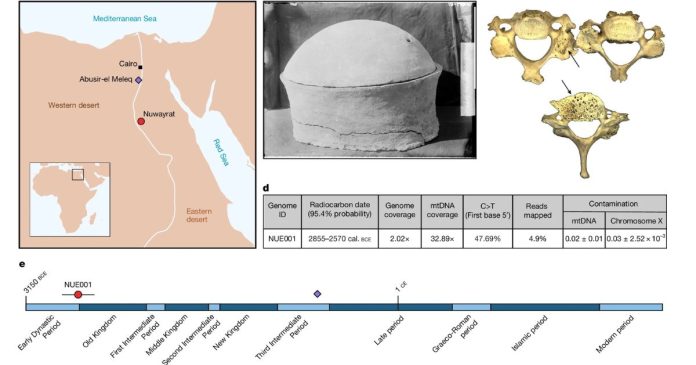

The research was led by the Francis Crick Institute and Liverpool John Moores University. It focuses on a single individual buried in a sealed ceramic jar at the Naqada (Nuwayrat) site in Upper Egypt.The results offer a rare and detailed genetic snapshot from a period central to the emergence of Egyptian civilization.

Burial Context and Individual Profile

The individual was an adult male who lived between 2855 and 2570 cal BCE. This was during Egypt’s shift from the Early Dynastic Period to the Old Kingdom. His remains were found inside a large, lidded pottery jar—a rare burial practice—at Nuwayrat, about 265 kilometers south of Cairo. Radiocarbon dating and context place the burial in Egypt’s formative state-building phase, marked by the unification of the Nile Valley and the rise of pyramid construction.

Skeletal analysis revealed extensive osteoarthritic changes, asymmetrical muscular development, and hip and knee modifications suggesting prolonged seated work. Wear on the ischial tuberosity and spinal curvature suggests he spent long hours in a squatting or cross-legged position. Muscular changes in his arms and feet support this idea. Researchers believe he was likely a potter, possibly using a rotating pottery wheel—a technology thought to have originated in West Asia and introduced to Egypt during this period.

Exceptional DNA Preservation

The sealed ceramic vessel provided an ideal microenvironment for the preservation of ancient biomolecules. Researchers extracted and sequenced DNA from a molar tooth, producing a 2x-coverage whole genome. This is the oldest authenticated genome from ancient Egypt.

This achievement overcomes a major challenge in ancient Egyptian genomics. The country’s hot, dry climate and common embalming practices often cause DNA to degrade. Previous genetic studies on Egyptian mummies, many dating to the Greco-Roman period, produced only partial genetic information. This new find, from a secure archaeological context and with minimal postmortem contamination, sets a new standard in ancient DNA recovery from the region.

Genetic Affinities and Population Structure

Population genomic analysis shows that the Nuwayrat individual’s ancestry mainly came from North African Neolithic populations. This aligns with local continuity in the Nile Valley. However, the genome also shows a significant (≈20%) ancestry component from the eastern Fertile Crescent, specifically the Levant and Mesopotamia.

This admixture matches archaeological evidence of growing contact between Egypt and its Near Eastern neighbors in the late 4th and early 3rd millennia BCE. The findings suggest that people moved between regions, not just ideas or goods. This movement played a key role in shaping early Egyptian society.

Previous studies hinted at Near Eastern influences in Egyptian pottery styles and administration. However, this is the first direct genetic proof of Fertile Crescent ancestry in an Egyptian from this early period.

Rethinking Social Stratification

The individual’s burial context and skeletal pathology suggest that he lived and died as a laborer, possibly with specialized skills. Yet his interment within a large pottery jar—likely produced by himself or his peers—and the careful placement of his body reflect a level of social recognition. This challenges traditional interpretations of rigid class structures in early Egyptian state formation and suggests a more nuanced view of status among skilled artisans.

Moreover, the use of the burial jar may have had symbolic or occupational associations. Researchers raise the possibility that this practice, though rare, was part of a localized tradition, or perhaps a personalized mortuary gesture reflecting the deceased’s profession.

Broader Implications for Ancient Migration

The presence of Near Eastern ancestry in a southern Egyptian burial raises new questions about the scale and routes of early human migration in northeastern Africa. The genomic data indicates that gene flow from the Fertile Crescent reached Upper Egypt by the early Old Kingdom—much earlier than previously documented.

This supports a growing body of evidence that Egypt, rather than being a culturally isolated Nile-centered civilization, was part of a broader interregional network extending across the eastern Mediterranean and western Asia. Trade, technology transfer, and population movement were deeply interwoven into Egypt’s emergence as one of the world’s earliest complex societies.

Expert Perspectives

Dr. Pontus Skoglund, lead geneticist at the Francis Crick Institute, emphasized the importance of burial context in DNA preservation:

“Mummified individuals are probably not a great way to preserve DNA. In this case, it was the ceramic burial that gave us such unprecedented molecular access.”

Dr. Joel D. Irish, bioarchaeologist at Liverpool John Moores University, noted that physical adaptations in the skeleton point to specific motor activities—possibly the operation of an early potter’s wheel—offering rare insight into daily labor practices in early dynastic Egypt.

Daniel Antoine, head of physical anthropology at the British Museum, described the study as “highly significant,” and called for further genome sampling across Egypt’s archaeological record to better understand its ancient population diversity and mobility.

Future Directions

The authors highlight that while this genome provides critical insight into early Egyptian population history, it is only a single data point. Broader conclusions about regional genetic diversity and long-term population dynamics will require additional samples across space and time.

Nevertheless, this study sets a new benchmark for ancient DNA research in Egypt and opens promising new directions for understanding the biological and social dimensions of one of the world’s earliest state-level societies.

References:

Schuenemann, V.J., Skoglund, P., Irish, J.D. et al. (2025). A 4,500-year-old Egyptian genome reveals ancient Near Eastern ancestry. Nature, 625(7838), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09195-5