The discovery of 5000-year-old whale-bone harpoons in southern Brazil has upended long-standing assumptions about the origins of large whale hunting. While Arctic and subarctic cultures have traditionally been credited with pioneering this practice around 3500–2500 years ago, new evidence from sambaqui sites in Babitonga Bay suggests that Indigenous Brazilian communities were actively hunting baleen whales. Including humpbacks and southern rights a millennium earlier. This revelation demands a deeper interrogation, particularly of the maritime technology that made such feats possible. Were these ancient whalers truly equipped to pursue and subdue multi-ton leviathans in open coastal waters? And if so, what kind of vessels did they use; and how do those presumed boats hold up under scrutiny?

Whale Hunting Before the Arctic: A Timeline Rewritten

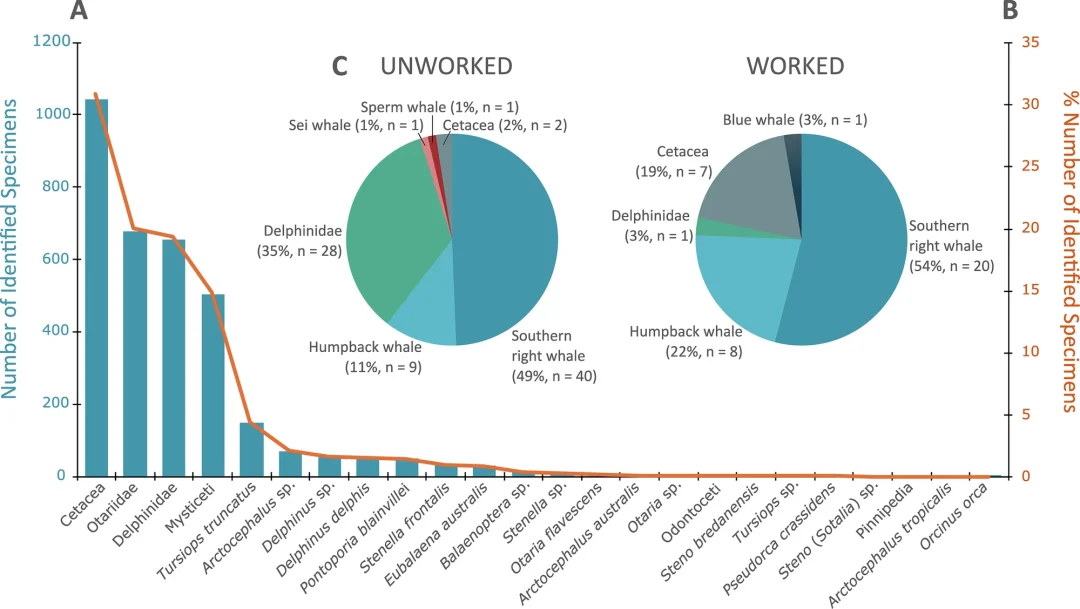

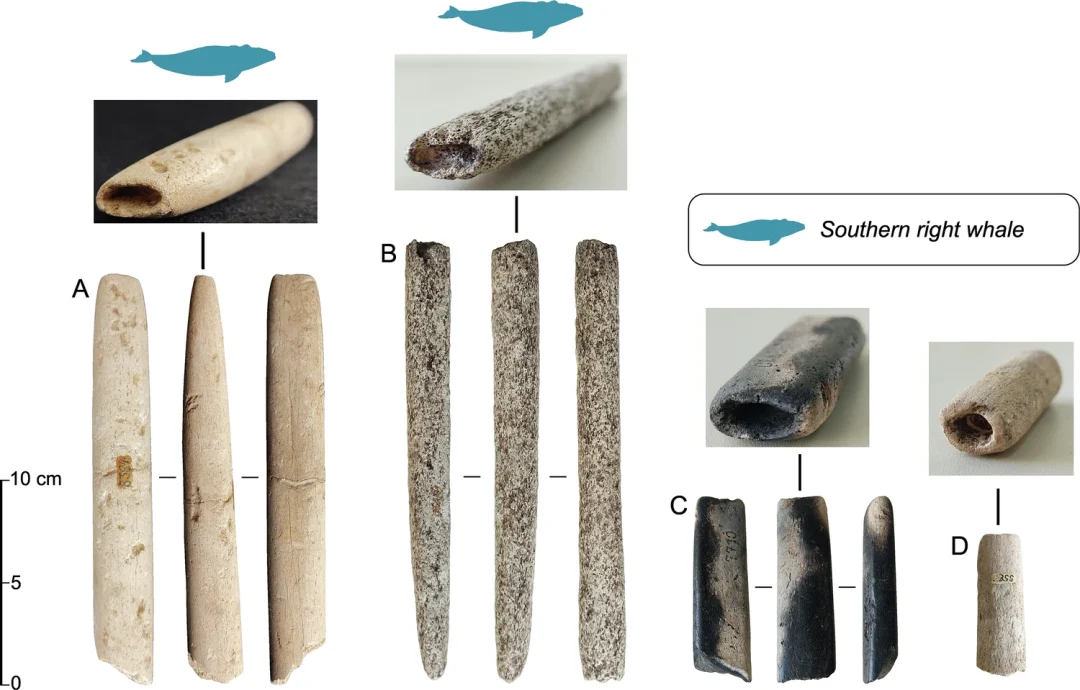

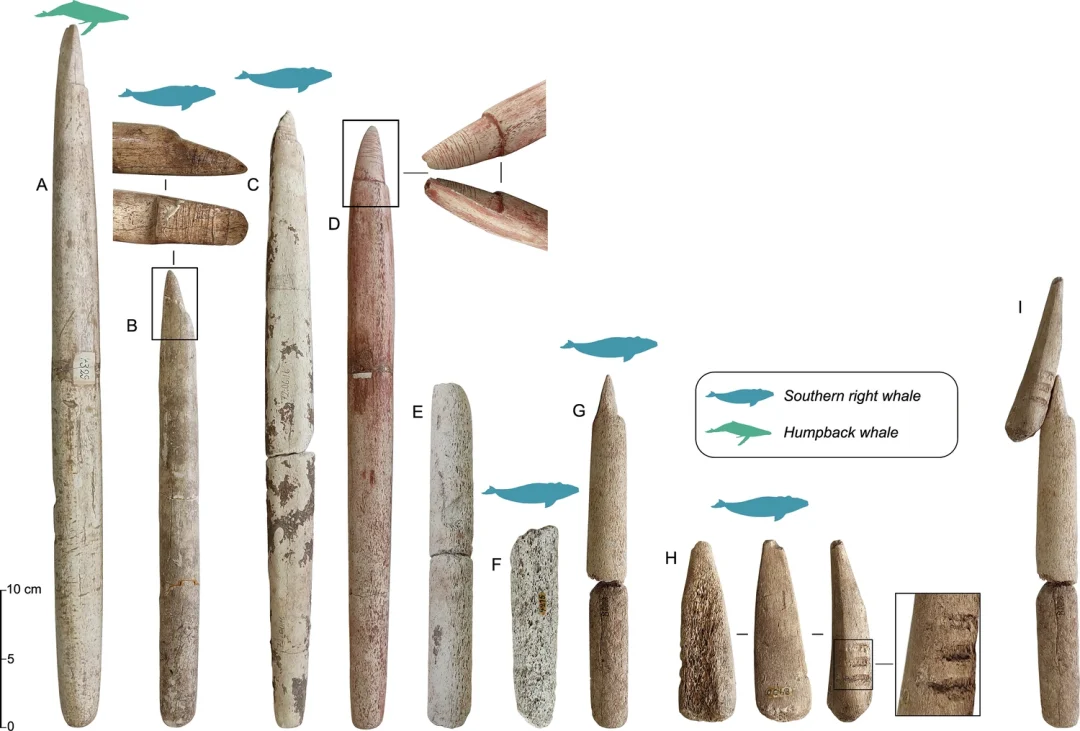

Sambaquis are ancient shell mounds built by coastal communities in southern Brazil, and they are famous for their large quantities of marine mammal bones. But until recently, the prevailing view held that whales were scavenged opportunistically, not hunted. That view is no longer tenable. Molecular analysis using ZooMS (Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry) has confirmed the presence of worked and unworked bones from humpback whales, southern right whales, and even blue and sei whales. More strikingly, several bone harpoon foreshafts and socket pieces bear unmistakable hallmarks of active hunting technology. These bones have been radiocarbon dated to nearly 5000 years ago. They include beveled ends for hafting, grooves for securing barbs, and hollowed sockets for detachable points.

The implications are profound: not only were Sambaqui peoples targeting large baleen whales, but they were doing so with specialized tools and cultural reverence, as evidenced by the inclusion of harpoon components in funerary contexts. This positions southern Brazil as one of the earliest centers of systematic whaling, predating Arctic traditions by over a millennium.

A Whale of a Question

Here’s where the inquisitive lens sharpens. The harpoons are real. The whale bones are real. The cut marks, the burial associations, the species identifications, all real. But what about the boats?

The archaeological record is silent on preserved watercraft from this period in Brazil. No dugouts, no planks, no lashings. Yet the scale of the prey (humpbacks reaching 30–50 feet and weighing up to 40 tons) demands a serious reassessment of what kind of vessel could have supported such hunts. Even if we assume the whales were targeted in shallow coastal waters, the logistics of approaching, striking, and retrieving such massive animals require more than casual paddling.

Let’s consider the forces involved. A harpooned whale, even a juvenile, would thrash violently. The recoil alone could capsize a small canoe. The retrieval line, likely made of sinew or plant fiber, would need to be anchored to a vessel with enough mass and stability to absorb the shock. And if the strategy involved multiple boats, then coordination, maneuverability, and endurance become critical.

Dugouts, Catamarans, or Something Else?

Ethnographic analogs from later Indigenous groups in South America and Polynesia offer some clues. Dugout canoes carved from massive tree trunks could reach lengths of 10–15 meters and carry several individuals. Some were stabilized with outriggers or paired into catamarans. But even these designs strain under the demands of whale hunting.

Let’s model a hypothetical scenario. A 12-meter dugout with a beam of 1 meter, carrying three hunters and gear, might weigh 500–700 kg. Add the dynamic forces of a harpooned whale, and the vessel would need to resist lateral torque, maintain directional control, and avoid capsizing. Without outriggers or ballast, the risk of rollover is high. Moreover, the absence of sails or advanced propulsion means the hunters would rely entirely on paddling; limiting speed and range.

Could they have used shore-based strategies, striking whales from shallows or estuarine bottlenecks? Possibly. But the presence of deep-water species like blue and sei whales complicates that theory. These whales do not frequent shallow bays and are unlikely to strand naturally in large numbers. Their bones, found in sambaquis, suggest offshore engagement.

Harpoon Design and Tactical Implications

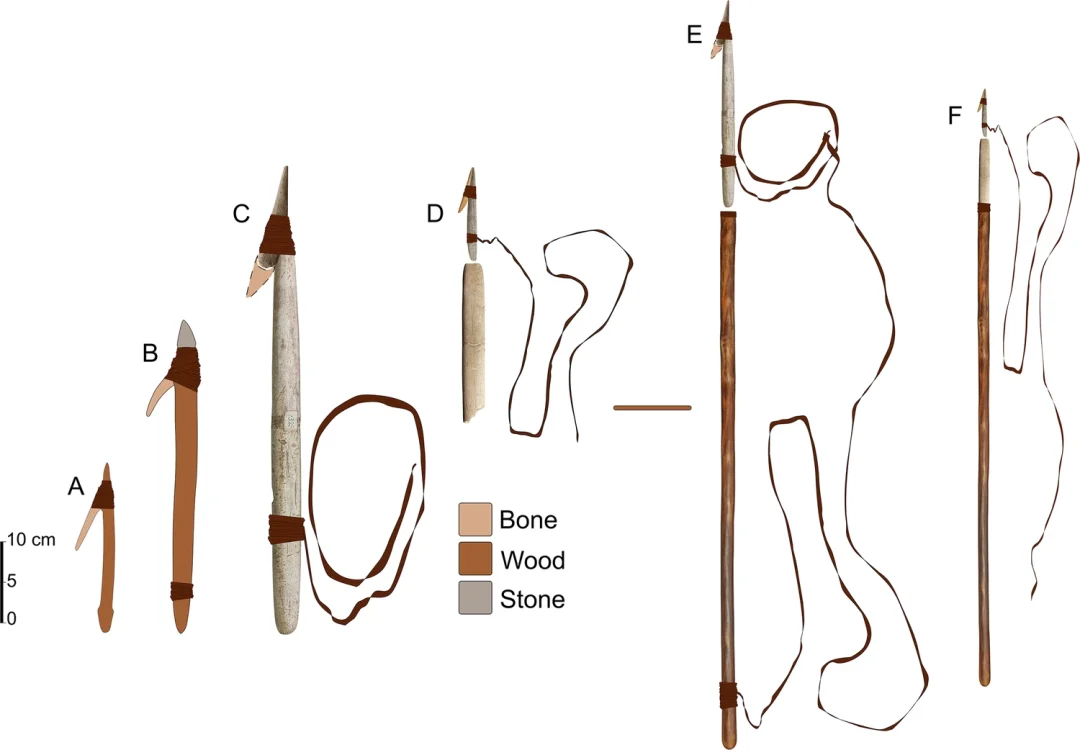

The harpoons themselves offer further clues. Two distinct types were identified: socket pieces for detachable heads and bevelled foreshafts for side-barbed points. Both designs imply a modular system (shaft, foreshaft, point, and line) optimized for penetration and retention. The bevelled points, some with hafting grooves, resemble Chilean harpoons dated to 4500 cal BP, but the Brazilian examples are older and made from whale bone rather than wood.

This choice of material is telling. Whale bone is dense, resilient, and buoyant. Its use suggests not only symbolic value but functional superiority. The foreshafts, some over 50 cm long, would have added weight and momentum to the strike, increasing penetration depth. But they also imply a need for precise handling. Which again raises questions about boat stability and hunter coordination.

Reconsidering Vessel Size and Maritime Capability

The scale of the whales involved forces a fundamental reassessment of the watercraft traditionally assumed for Sambaqui hunters. The assumption of small, nearshore canoes becomes increasingly untenable when considering real world logistics. A humpback or southern right whale, even at subadult size, represents a multiton mass capable of generating violent recoil forces the moment a harpoon strikes. Any vessel participating in such a hunt would need to withstand sudden lateral torque, rapid directional changes, and the drag of a fleeing whale.

These demands point toward boats far larger and more stable than simple dugouts. The evidence suggests that Sambaqui communities must have engineered substantial seagoing vessels. Boats crafted with enough length, beam, and structural reinforcement to absorb shock, support multiple crew members, and anchor retrieval lines without catastrophic instability. Such boats would not only enable whale hunting but also reflect a sophisticated maritime tradition that has yet to be fully recognized in the archaeological record

To resolve these questions, experimental archaeology must step in. Reconstructing plausible boat designs using local materials (wood, fiber, resin) testing them under simulated whale-hunting conditions could yield insights.

Implications for LongDistance Seafaring

If Sambaqui vessels were large and stable enough to engage whales offshore, then their capabilities likely extended well beyond hunting. A boat that can survive the thrashing of a harpooned whale is, by definition, a boat capable of traveling significant distances along the coast or even across open stretches of ocean under favorable conditions. This possibility reframes the maritime landscape of prehistoric Brazil.

Large vessels could have facilitated seasonal movement following whale migrations, long distance exchange between sambaqui settlements, or exploratory ventures into new coastal zones. The absence of preserved boats is not surprising given the poor preservation conditions of subtropical environments, but the indirect evidence strongly implies a seafaring capacity far more advanced than previously assumed. These communities may have operated within a broader maritime network, one that blended resource gathering and mobility into a cohesive ocean-oriented lifeway.

Conclusion: Reframing the Maritime Legacy

The evidence from Babitonga Bay is clear: ancient Brazilians hunted whales 5000 years ago, using sophisticated bone harpoons and embedding cetacean symbolism into their cultural fabric. But the forensic challenge remains: what kind of boat made this possible?

Until direct evidence emerges, we must triangulate from tool design, species behavior, and ethnographic analogs. The answer may lie not in a single vessel type but in a system, a coordinated maritime strategy that blended engineering and ecological knowledge. As we continue to unearth the secrets of the sambaquis, let us not underestimate the maritime legacy of these early whalers, nor the unanswered questions that ripple beneath the surface.

For More on ancient sea faring check out Ancient Egyptian Ships: Large Cargo Transport Vessels