Caral Supe stands as the oldest known civilization in the Americas. People there built massive pyramidal structures, located today in northern in Peru, around 5000 years ago. These pyramid like mounds challenge ideas about early societies. They show advanced organization without pottery or metal tools.

The Caral Supe sites sit in the arid Supe Valley, north of Lima. Dry conditions preserved the ruins well. Ruth Shady Solís led key excavations starting in 1994. Her team dated the sites to 3500 BCE. This pushed back timelines for complex societies in the New World over a millennia.

Visitors see six large pyramids at the main Caral site. The largest measures 150 meters wide and 20 meters high. Builders used stones and shicra bags filled with rocks. These methods allowed quick construction. Workers stacked layers over time.

Image Source: Inca Trail Machu

Discovery of Caral Supe Sites

Paul Kosok first spotted some mounds in 1948 while flying over the area. Back then, archaeologists shrugged them off. The mounds were mapped in 1975 by Carlos Williams. His sketches gave more context to what potentially lay buried. Leading to Ruth Shady’s excavations in 1994.

In 2001, Shady published findings in Science magazine. She worked with Jonathan Haas and Winifred Creamer. Their paper stunned the world. Caral Supe predated the Olmec by 1500 years. UNESCO named it a World Heritage Site in 2009.

Recent digs uncover more. In July 2025, Shady unveiled Peñico, a 3800-year-old city. It links to Caral Supe trade networks. The site sits 12 kilometers from the main area. Excavations show walls and ceremonial spaces. Peñico Courtesy Peruvian Ministry of Culture

Peñico added to an earlier find in January 2025 at Chupacigarro. Archaeologists there unearthed a pyramidal structure. Caral Supe’s Architectual foorprint just keeps growing.

Society and Economy in Caral Supe

In the heart of the Supe Valley, the people of Caral Supe built a society unlike any other in the ancient world. Archaeological digs reveal no weapons, no signs of battle; only evidence of cooperation and communal effort.

Their cities rose not through conquest, but through coordination. Elite planners oversaw massive construction projects, while farmers cultivated cotton, squash, beans, and early maize, channeling water from the Supe River through carefully managed irrigation systems.

Trade pulsed through the region like lifeblood. Coastal settlements such as Áspero supplied seafood, while inland groups brought obsidian and stone. Cotton, grown in abundance, was spun into nets that made fishing more efficient. This exchange of goods and knowledge helped build a thriving economy, connecting communities across valleys and time.

Music echoed through ceremonial plazas. Excavations uncovered 32 flutes carved from pelican and condor bones, and 37 cornets shaped from deer and llama remains. These instruments likely accompanied rituals, their sounds woven into the spiritual fabric of daily life.

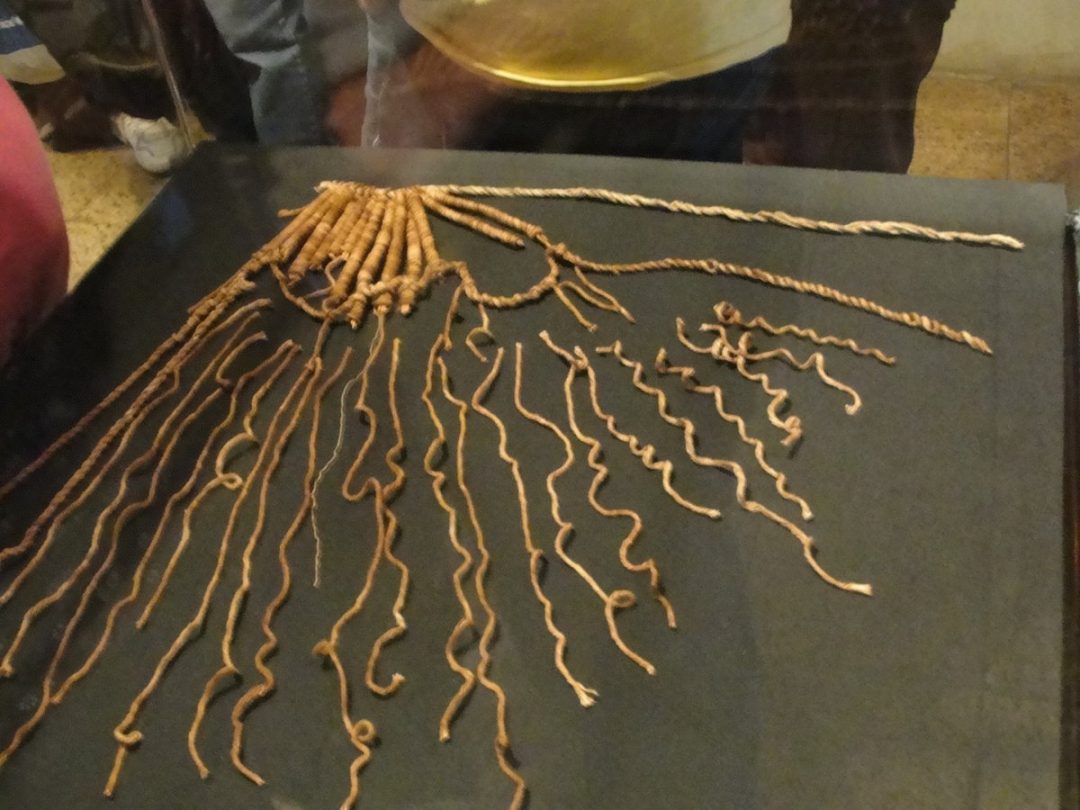

Quipus, knotted strings used for record-keeping, hint at an early form of administration, suggesting that Caral Supe tracked resources and events with remarkable sophistication.

Quipu on Display at Museo de Sitio Caral

At its peak, the city of Caral housed around 3,000 people, while the broader Norte Chico region supported up to 20,000 across a network of interconnected sites. These settlements, spread over 80 square kilometers, shared architectural features and ceremonial layouts, reflecting a unified cultural vision.

Architecture of Caral Supe Pyramids

Builders created stepped platforms, not true pyramids. Each mound had flat tops for ceremonies. Sunken plazas sat nearby. The Amphitheater Pyramid features a circular court. It measures 100 meters across.

Structures evolved over centuries. Layers show rebuilds. Astronomy guided layouts. Alignments match solstices. This tied rituals to the stars.

Image Source: Inca Trail Machu

No wheel or metal tools existed. Workers carried stones by hand. Shicra bags made transport easy. These reed containers held small rocks.

Parallels with Ancient Egypt

Around 3000 BCE, the builders of Caral Supe were already shaping monumental platform mounds in the Supe Valley of Peru. Across the Atlantic, Egypt’s Step Pyramid of Djoser would not rise until about 2630 BCE, under the guidance of Imhotep. That structure began as a simple mastaba, gradually evolving into a layered, stepped form, mirroring, in concept if not in contact, the tiered designs seen in Caral.

Both civilizations mobilized vast labor forces to raise these enduring monuments. In Egypt, the focus was funerary pyramids built as eternal homes for divine kings. In Caral Supe, the emphasis was communal. Their mounds supported public rituals, not royal tombs. Each society harnessed the power of rivers: the Nile in Egypt, the Supe in Peru. Irrigation transformed arid landscapes into fertile ground, sustaining agriculture and fueling growth.

Trade routes extended their reach. Egypt exchanged goods across the Mediterranean and Red Sea, while Caral Supe connected coastal fishermen with inland traders who brought obsidian and stone. Hierarchies emerged to manage labor and resources, yet the two cultures developed in complete isolation from one another.

Despite the distance, both left behind monumental architecture that speaks to a shared human drive, to build, to organize, to ritualize. Egypt’s pyramids enshrined the dead. Caral Supe’s mounds celebrated the living. And while Egypt’s monuments are more widely known, Caral Supe may have laid its first stones even earlier.

Legacy of Caral Supe

Caral Supe left a lasting imprint on the Andean world. Its irrigation techniques, first developed over 5,000 years ago, were later adopted by cultures like Chavín and spread southward across the region.

In 2025, discoveries at Peñico added fresh depth to the Caral Supe narrative. Located just 12 kilometers from the main site, this 3,800-year-old city revealed ceremonial architecture and trade links that reinforce Caral’s central role in early Andean civilization.

The parallels with ancient Egypt remain striking. Though separated by oceans and cultures, both societies built stepped monuments around the same time, organized large labor forces, and tied their rituals to celestial cycles. These similarities reflect a shared human impulse to build, to gather, and to remember.

Archaeologists study both civilizations for clues about early urban life. They find common threads in social organization, ritual architecture, and long-distance trade. Yet the differences are just as revealing. Egypt’s pyramids enshrined the dead; Caral Supe’s mounds celebrated the living. Egypt centralized power under divine kings; Caral Supe emphasized communal space and cooperation.

Ongoing Research in Caral Supe

Exploration continues beyond the main Caral Supe site, as archaeological teams fan out across the Supe Valley in search of satellite settlements and undiscovered pyramidal structures. Equipped with drones and remote sensing tools, researchers map hidden platforms buried beneath centuries of sediment and vegetation. These technologies reveal architectural patterns that echo the monumental designs of Caral, suggesting a broader urban network still waiting to be uncovered.

Caral’s Legacy

The legacy of Caral Supe challenges long-held assumptions about where and how civilization began. It shows that complexity did not radiate from a single origin point. Instead, it emerged independently in the Americas, shaped by local rivers, regional trade, and a peaceful social order. The stepped mounds of Caral still stand, not just as ruins, but as evidence that the ancient world was more interconnected in spirit than we once believed.

For More on Quipu’s Check out Quipu: Incas Ancient Knotted Codex