Incised stone artefacts from the Levantine Middle Palaeolithic reveal early hominid cognition, artistic expression, and cultural development. Researchers studied engraved Levallois cores and other lithics to explore their symbolic and functional roles. These markings reflect complex human behavior within a broader evolutionary framework.

Previous Studies

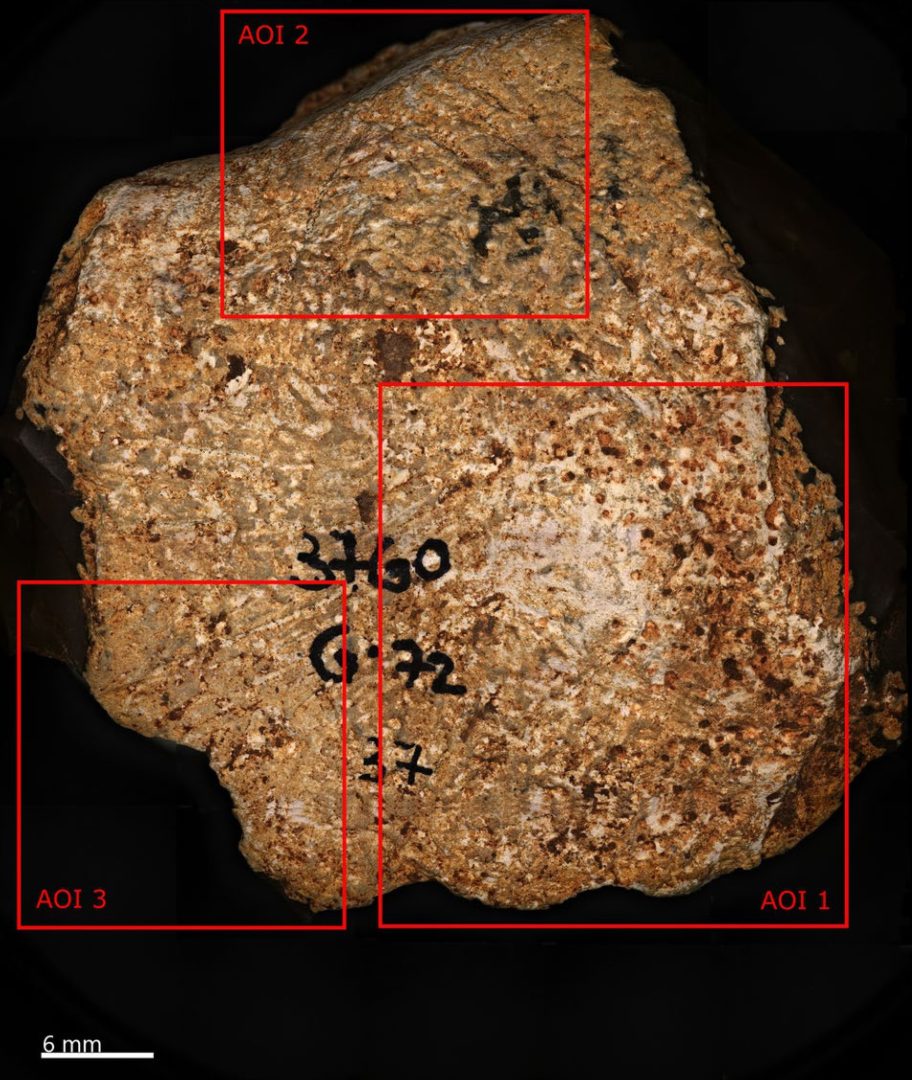

the cortex

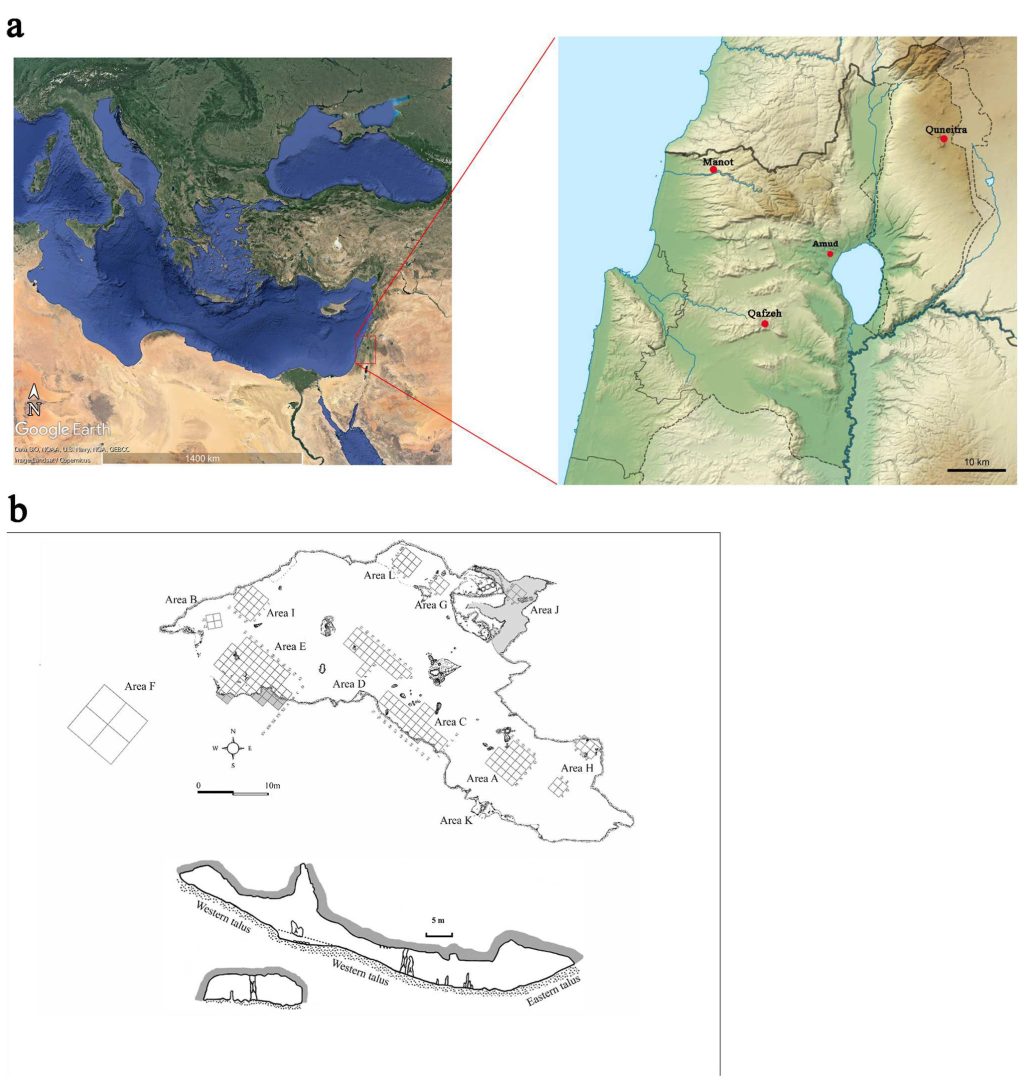

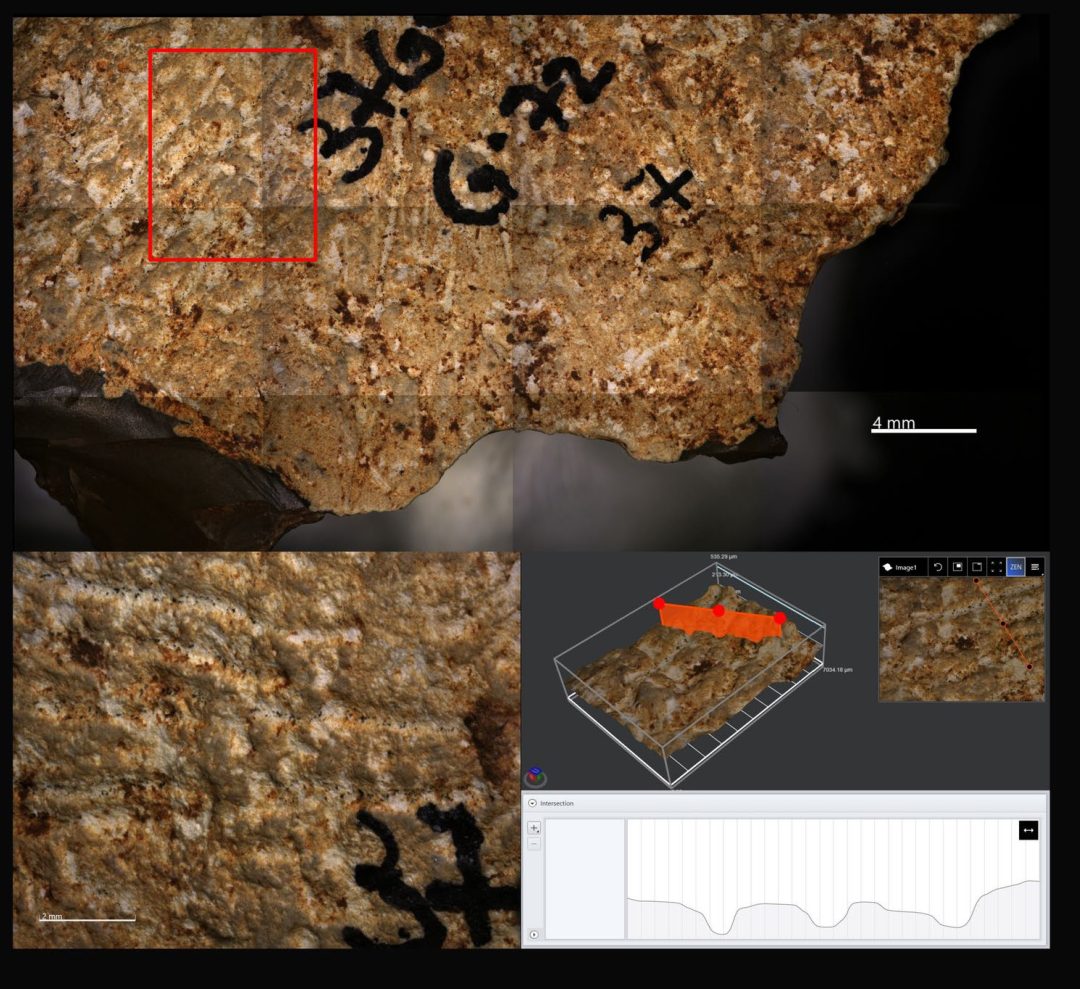

Archaeological evidence of non-utilitarian incised artefacts has long been considered a marker of cognitive sophistication among early hominins. The studies done examined artefacts from Manot, Qafzeh, Amud, and Quneitra, applying advanced 3D surface analysis to assess the intentionality behind the engravings. The findings highlight a recurring pattern of deliberate incisions, with geometric regularity and spatial organization indicative of purposeful design. These artefacts contribute to ongoing discussions regarding the emergence of abstract thinking and symbolic behaviour among Neanderthals and early modern humans.

Manot Cave

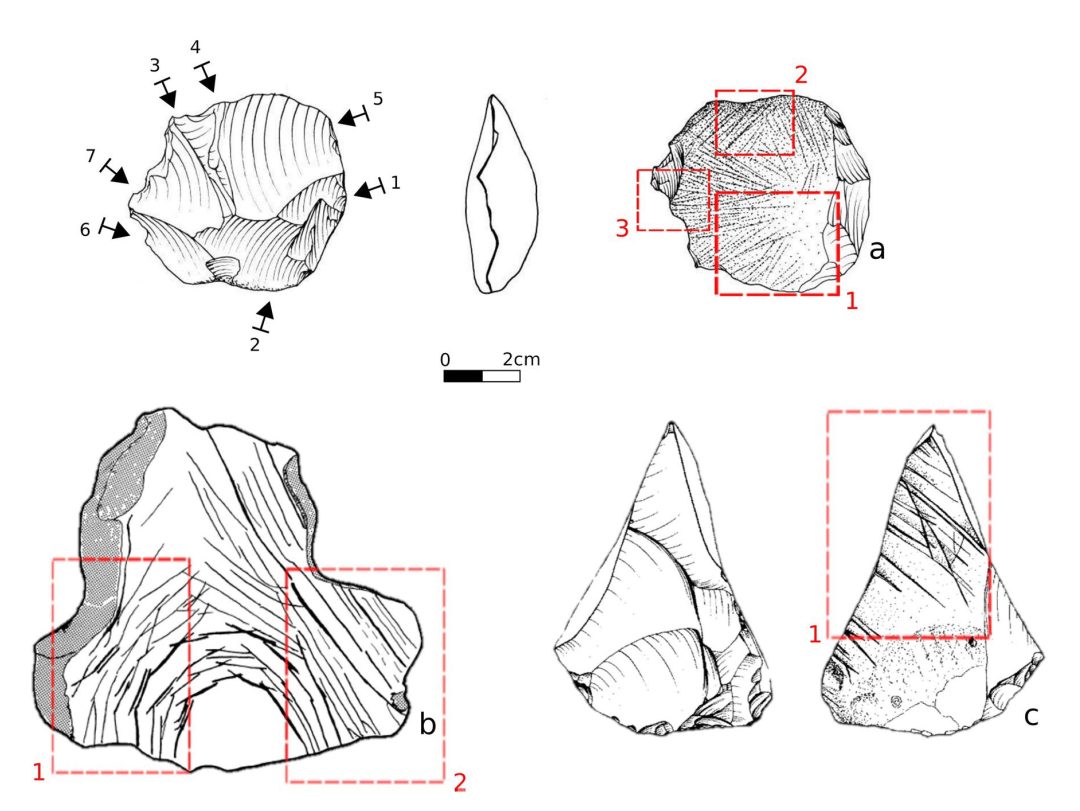

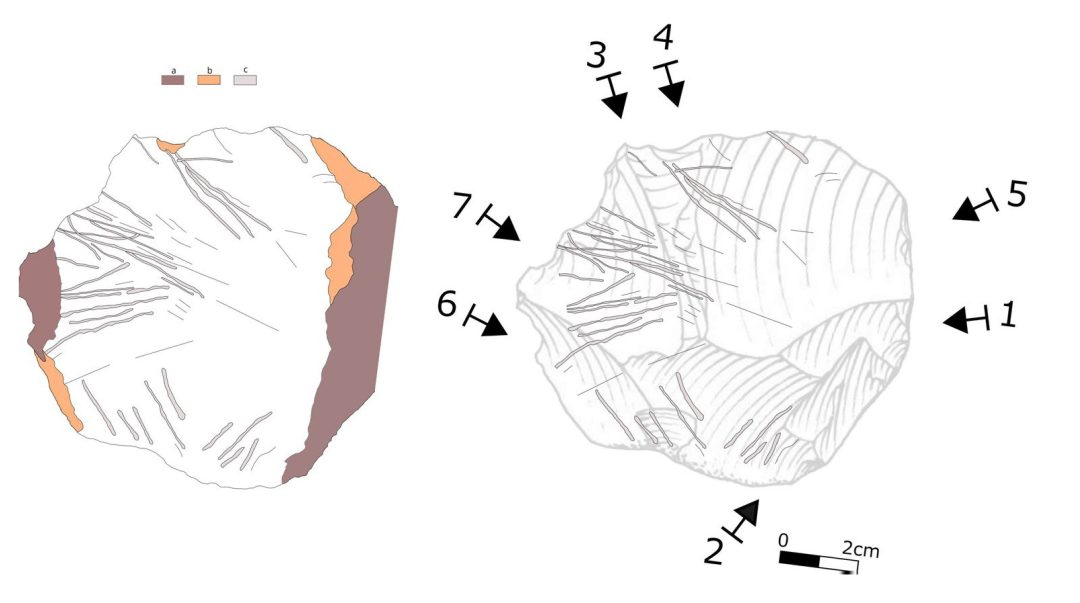

The incised Levallois core from Manot Cave is particularly striking, displaying a fan-like pattern of converging incisions. The geometric arrangement suggests intentionality, as the markings are not random but follow a deliberate orientation. The supporting academics argue that the engravings likely predate the final knapping stage, reinforcing the hypothesis that they served a purpose beyond mere tool preparation. This aligns with other Middle Palaeolithic sites where engraved artefacts have been interpreted as early expressions of symbolic thought.

Qafzeh & Quneitra

The engraved core from Qafzeh and the plaquette from Quneitra further support the idea of intentional, non-utilitarian engravings. The Qafzeh artefact, found in association with ochre and human burials, suggests a possible ritualistic or symbolic function. Meanwhile, the Quneitra plaquette exhibits a series of nested semi-circular engravings, a pattern that implies an aesthetic or communicative intention. These artefacts collectively point to the repeated and independent emergence of engraving practices across different regions and time periods.

In contrast, the artefacts from Amud Cave present a more ambiguous case. Researchers observed overlapping striations on the blade and flake, but irregular patterns suggest tool use—not symbolic engraving. The study emphasizes that not all incised markings are artistic or symbolic. Some may serve functional roles, like edge preparation or abrasion.

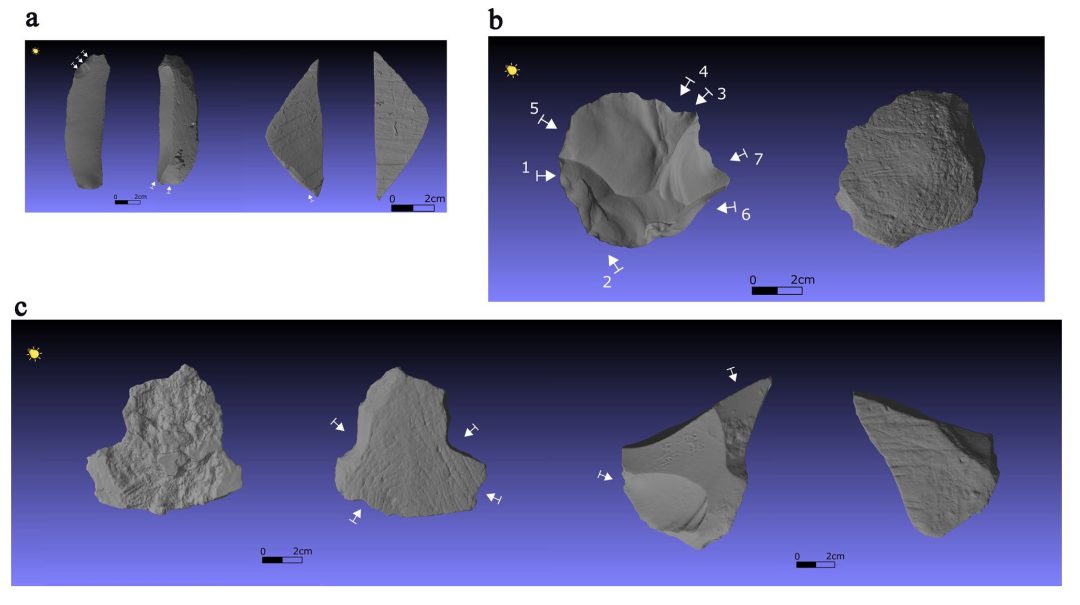

b Illustration of the engraved artefacts of Manot, c Illustration of the engraved artefacts of Quneitra (to the left) and Qafzeh (to the right)

The Evidence

Findings from Manot, Qafzeh, and Quneitra support the idea that Middle Palaeolithic hominids deliberately engraved stone artifacts. Artifacts from multiple sites and periods show engraving was widespread, not isolated. These discoveries challenge the belief that symbolic behavior belonged only to Homo sapiens. They highlight the creativity and intellect of Neanderthals and other archaic hominids.

incisions.

Researchers stress the complexity of interpreting prehistoric engravings and call for a multidisciplinary approach. Engravings at Manot, Qafzeh, and Quneitra suggest intentional symbolic behavior. Amud artifacts show the need to separate functional markings from abstract ones. Refining our understanding of early creativity helps reveal the origins of symbolic thought and its role in human development.

3D model and GIS inspection. The different colours mark, a non-cortical flaking scars, b cortical flaking scars, c deepest incisions. Narrow lines represent shallow incisions, right. Engraved incisions are superimposed on the map of the ventral surface, showing the deviation of the striation from flake orientations on this surface.

My Thoughts

As a personal note, I would like to add that, although the research presented denotes a commendable sensibility to several problems within archaeology, it still fails to recognize what should be evident. There remain underlying assumptions that, though deeply entrenched in academic discourse, are seldom subjected to the scrutiny they deserve. Two critical points demand re-evaluation: first, the presumption that both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals were cognitively limited in comparison to modern humans, and second, the problematic use of the term Proto-Symbolism, a linguistic construct that carries unintended philosophical weight and reveals an inherent bias in the academic understanding of early symbolic expression.

Asumptions

The notion that archaic hominids possessed a lesser cognitive capacity is an assertion rooted in assumption rather than demonstrable evidence. Nowhere in the archaeological record is there any material confirmation that Neanderthals or early Homo sapiens were intellectually inferior. This belief, inherited from an evolutionary framework that demands a linear progression of intelligence, has transformed into an unquestioned dogma. The discipline of archaeology, influenced by the overarching paradigm of evolutionary anthropology, often operates within a preordained schema in which cognitive development is presumed to follow a gradual and hierarchical trajectory.

But what if this premise is flawed? What if the intellectual and creative faculties of these early humans were not rudimentary, but rather distinct in ways we have yet to comprehend? The presence of intentional engravings, structured technologies, and complex social behaviours suggests not an emergent intelligence, but an already-established cognitive sophistication that requires no artificial scaffolding to justify its existence.

Terminology

Equally problematic is the term Proto-Symbolism, a phrase frequently employed in discussions of early symbolic behavior. Proto, meaning before, implies a developmental stage, a precursor to something fully realized. Yet, symbolism is not a phenomenon that can exist in degrees. It is either present or it is not. To speak of Proto-Symbolism is to suggest that these engravings, markings, and abstract designs were somehow less than symbolic, that they represent an incomplete or primitive attempt at meaning-making. But how can one conceptualize a form of symbolism that is not, in itself, symbolic? This is a contradiction rooted in modern academic language rather than empirical reality. What the record shows is that symbolism, as far back as we can trace it, was fully formed. The problem is not with the artefacts themselves but with our interpretation of them, constrained by our own imposed chronology of human intellectual development.

What we see in the archaeological record is not the birth of symbolic thought, nor the origins of cognitive complexity, but simply the earliest material evidence we have uncovered so far. This distinction is crucial. The discovery of engraved artefacts, ochre use, and structured spatial organization does not indicate the emergence of these behaviours at that moment in time; it only tells us that these behaviours were already well in practice by that period. The absence of evidence does not equate to the evidence of absence. To claim that symbolism began with these artefacts is to mistake the limits of our discoveries for the limits of history itself.

Rethinking

A re-examination of these assumptions is long overdue. If we free ourselves from the constraints of an evolutionary ladder model, one where intelligence and cultural complexity must always be progressing upwards, we can begin to perceive the past more clearly. Rather than viewing Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens as mere stepping stones toward modernity, we must recognize them as fully realized cognitive beings, capable of abstraction, creativity, and meaning-making in ways that may be different from, but not lesser than, our own. By challenging the dogmas that persist in our field, we open the door to a more nuanced and accurate understanding of early human expression.

Bibliography:

Incised stone artefacts from the Levantine Middle Palaeolithic and human behavioural

Mae Goder‑Goldberger, João Marreiros, Eduardo Paixão, Erella Hovers

2025

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-024-02111-4